Written by Museum Archives Assistant Natalie Conrad

The story of Wingham’s picture house begins in earnest in 1908, when local undertaker William Briton opened the Wonderland. It was located north of the town hall on Josephine Street, in a building that had formerly been a farm machinery dealership. In March 1909 came the first of many changes in ownership when the theatre was purchased by George Corbett. Corbett renamed his new business the Lyceum, a name that would stick until the theatre closed nearly a century later.

Under Corbett’s ownership, the Lyceum Theatre showed both films and concerts. However, these new forms of local entertainment were not without their problems. There were complaints of the theatre being cramped, with improper lighting, and of the pictures being generally difficult to see.

In 1912, Lachlan Kennedy would purchase the theatre from Corbett. Promising that nothing objectionable would be shown at the theatre, the opening film footage was of the Titanic disaster. While some today might find showing disasters for entertainment objectionable, this was certainly not what they meant in the day. In 1914, Kennedy took to renovating the theatre. The Lyceum was enlarged and redecorated, the ventilation improved, and a new electric player piano installed.

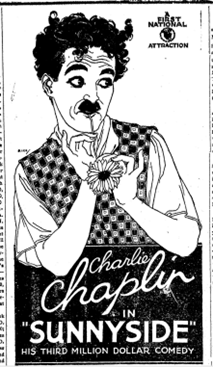

Advertisement promoting Charlie Chaplin in “Sunnyside”. Published in the Wingham Advance, Jan. 22, 1920.

The early 20th century saw considerable backlash around the introduction of movie theatres, with both moral and health concerns. Indeed, as David Yates reports, not all residents approved of having a picture house in town, with some seeing it as a symbol of modern decadence. In 1924, Dr. J. Middleton of the Provincial Board of Health stated that moving pictures were bad for the eyesight of the young, and time spent sedentary in a stuffy theatre would be put to better use outside. (i)

“Fearing Hollywood Babylon in Wingham” (ii), in 1915 town council proposed a hundred-dollar fee for a license for the theatre. Today, this would amount to about $2,700—a fine surely meant to be prohibitively expensive for a small business. Rallying against this, Kennedy argued the theatre paid no small sum to the town in electricity and business taxes, as well as employing four. Council eventually relented somewhat, with Reeve Mitchell admitting the movie house was a good place for youths—or at least better than pool halls and hotels. For the lesser evil of entertainment, a revised, lesser fee of $60 was levied.

The Wingham Advance reports that in October 1921, Robert VanNorman purchased the Lyceum from Kennedy and Maxwell, describing plans to overhaul the building and to put on a new front. In an opinion column published two months later, said front would be described as “… a decided improvement [that] adds greatly to the appearance of the main street.”(iii) The theatre would go on to re-open on Nov. 10, 1921, with new and reduced admission prices. Twenty cents for adults, including war tax, and 10 for children, who must be accompanied by a parent or guardian.

June 1923 would see the Lyceum sell again, this time to Hyde Parker of Stratford. Curiously, the Advance reported that the theatre was sold to Parker by Mr. Kennedy, and not VanNorman. (iv) A short two years later came another change of hands. In December 1925, Parker sold the theatre to Captain William James Adams of Orangeville, who would come to be known simply as “Capt. Adams”. Adams was a sailor by trade, formerly in charge of the Greyhound, a famed Great Lakes passenger ship that regularly sailed out of Goderich. The ship’s three hour “Moonlight Cruises” and Detroit excursions were popular amongst local holidaymakers for many years, with the Goderich to Detroit trips operating from 1902 to 1927. (v)

Captain Adams and his son, Alton, would run the theatre for several decades, overseeing many major renovations. It can be assumed that changes to the theatre were made between 1925 and 1929. A retrospective issue published by the Advance-Times in 1929 states that he “… ha[d] completely renovated it, and made it an attractive place.”(vi) In June of 1930, however, the Lyceum would really be changed, inside and out—in the ballpark of a practically new building, and the installation of equipment for “talkies”, or movies with sound. Closure began on June 16, and it would re-open on Aug. 18. After congratulatory remarks that evening by Mayor Fells, the first show was Sally, a musical in Technicolor, which was standing room only, with a packed house. The building was described as being made of steel, brick, and concrete, and absolutely fireproof. New and improved capacity for “talkies” was complemented by a new seating capacity of 300, a new screen, hot water heating, improved ventilation, and a new lobby.

Upgrades, renovations, and general improvements were constantly being made under the ownership of the Adamses. In February 1937, new soundproofing; in April 1941, new seats; redecorating in 1944; in November 1946, new amplifiers of “greatly improved quality” (vii); and in 1948, a completely new sound system from Northern Electric, “making [the] local theatre one of the best in Western Ontario”, according to one Advance-Times contributor (viii).

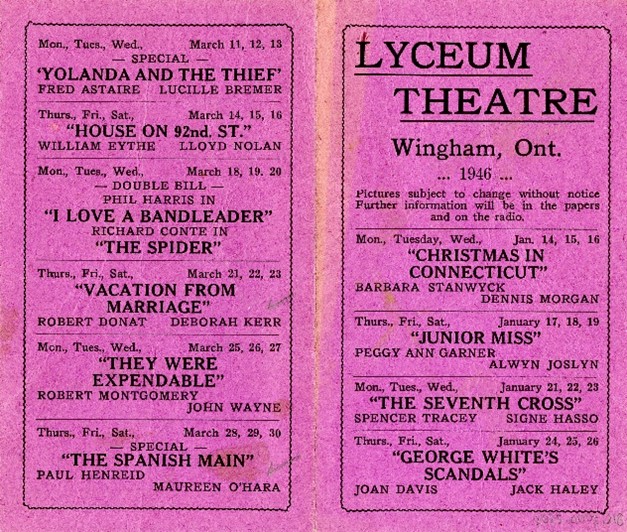

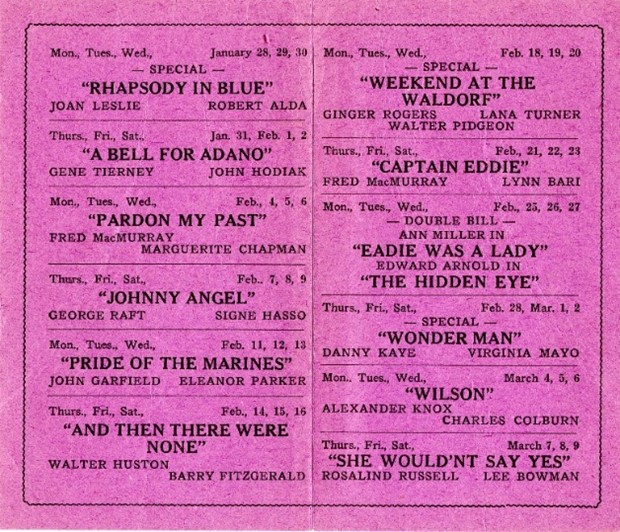

A Lyceum program from Winter 1946. From the collection of the Huron County Museum, 2025.0002.218.

Management was handed over to Alton Adams in 1942. Throughout the ’40s, the Lyceum would play its part in the collective war effort on the home front. In 1940, the theatre participated in a nationwide event in which admission to a show would be free with the purchase of two war saving stamps, costing 25 cents. The Advance-Times reports the event went well, with $294 of stamps sold and over 500 people attending. Tickets were donated for charitable purposes on many occasions— for one example, 600 tickets were presented to the Wingham Red Cross in March 1943.

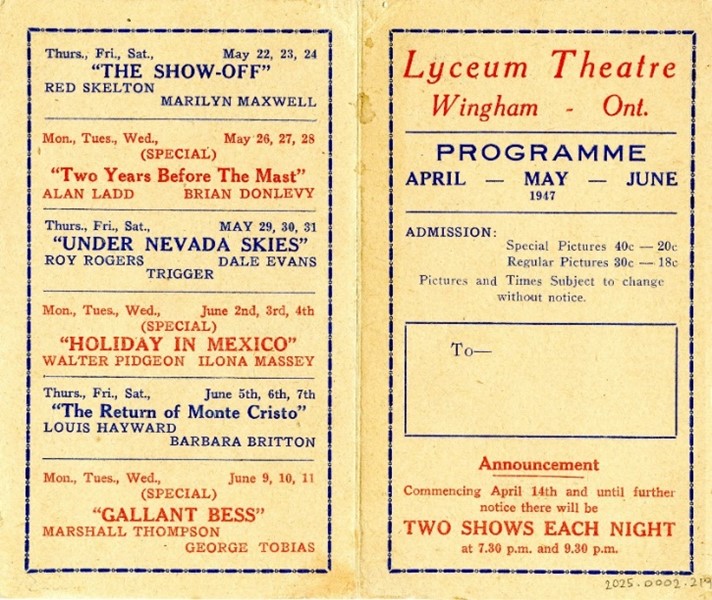

In March of 1947, new programs for the Lyceum Theatre would be rolled out. For April to June, they were ready at the end of the month and could be obtained by calling at the box office or mailing in one’s name. A permanent mailing list was in the process of being established.

One of the new Lyceum programs. From the collection of the Huron County Museum, 2025.0002.219.

With the advent of television in the home, small-town movie houses across the province would feel a loss, with many being forced to shut down. The Lyceum was certainly not unique in this regard: beginning in the mid-’50s, and over the course of the next two decades, would come repeated shutdowns and re-openings of the theatre.

In October 1954, the first Cinemascope picture to be shown in Wingham was The Robe. This came with another huge leap in theatre technology— “the new wide screen necessary for Cinemascope pictures, which give the effect of breadth and three dimensions without the use of glasses on the part of the spectators”.(ix) Always at the vanguard of these new innovations, the Lyceum was first in the area with Cinemascope.

Here comes what seemed the beginning of the end. Matinees at the Lyceum were discontinued in July 1955, for lack of interest. As early as February 1956, the first of several pieces forewarning the closure of the Lyceum were published in the Advance-Times. In the “Worth Thinking About” column, the author observed that the popularity of TV had begun to wreak havoc on community entertainment. It discussed hockey games, but more presciently, the small-town movie house and how many had been forced to close due to wanting patronage. The piece sagely remarked that the Lyceum was a top-of-the-line picture house, and it “would be a sad day for Wingham” should it be forced to close. (x)

In October of 1960, another piece would be published in the local news, urging community members to attend matinees, which were being given another try. At this point, the theatre had been operating only part-time, and the article once again ending on a warning note: “If the Lyceum were to close completely it would be a distinct loss to the community and it would be altogether likely that no other theatre would ever open its doors in Wingham”.(xi) Just under a year later, in September 1961, a similar announcement would be made—a trial period of matinees, despite their having been unprofitable in the past. By January of 1963, the Lucknow Sentinel was reporting that lack of patronage had forced opening hours down to Saturday and Sunday evenings. (xii)

Theatre attendance continued to dwindle, the warnings of local columnists apparently gone unheard. In April of 1963, it seemed it was finally going to happen. Unable to turn enough profit (after all, the Adams ran a business, not a public service), the Lyceum was to close its doors for good.

A heartfelt editorial, “Sorry To See It Go”, mourned the loss of a town institution and what was once a community hub.(xiii) It had, under two names, numerous owners, and with various fronts, served the community for five and a half decades. The editor expressed sincere regret, sympathy for Adams (who had hung on for as long as possible), and the opinion that Wingham would be the poorer for its loss.

Half a year later, in September 1963, the Advance-Times was reporting on a rumor about town—that the Lyceum, not in operation since March, had sold, and the purchaser intended to put it back in business. Only one week later, the buyer would be revealed: W.T. “Doc” Cruickshank, well-known resident and president of CKNX.

The theatre would re-open on Oct. 3, featuring the film The Longest Day, the story of the Allied landing on D-Day. Under new ownership, the Lyceum was to be back in operation six days a week, and the building was already in the process of being redecorated.

Another editorial, this one published on the theatre’s opening day, was pleased to see the lights back on at the Lyceum. However, the editor’s fears were not completely allayed. In a cautioning tone, it recalled that the Lyceum, for a decade, had experienced challenges faced by many small-town theatres. The town, according to the editor, was lucky that Adams had kept the business open as long as he did, and that even though it had been reopened, no one could expect the theatre to remain open without the support of the public.

Three years later, in May of 1966, yet another editorial—the topic and title, “Unwanted Amusements”. The editor was not amused by local youths complaining of having nothing to do, especially since their own disengagement had caused the decline of said amusements. Weekly dances at the Kin Pavilion had been cancelled, and it seems implied that the Lyceum was once again set to close. The editor writes, “[t]here will be a second gap when the Lyceum Theatre closes—also for lack of public support. The management of the theatre has brought first-class films to town and has made every effort to maintain the theatre, but now they have decided its operation cannot be continued on the present scanty attendance … There is no law which forces people of any age to attend dances or shows. This is a free country. But let’s not hear that plaintive cry that there is nothing to do in Wingham. It’s too late for that theme now.” (xiv)

Once again, however, the Lyceum appears to have been saved from closing its doors— in July 1966, an ad in the Advance-Times stated that the theatre would re-open on Aug. 3.

In March of 1967, the Lyceum would begin a six-week closure, re-opening mid-June. Operations seem to have continued to struggle into the 1970s, with the theatre lacking a snack bar and open only a few nights a week.

1973 would see the theatre purchased by John Schedler, a man with theatre experience from all over, but most recently employed at the Capitol in Listowel. In a long-form article published in the Advance-Times in January 1975, we hear of a new era for the local landmark. From when Schedler assumed management in August 1973, to the date the article was published, over $20,000 had been poured into improving the theatre. The lobby was entirely remodeled, the box office replaced, and the concession booth expanded. Almost half of the seats in the theatre were ripped out, providing patrons a better view of the screen, and many of the chairs were brand new. Perhaps the most important improvement to the moviegoing experience was a new automatic projection system. With the new projector, the number of times film reels had to be changed per showing went from five to one, and it took care of “virtually all visible errors”. (xv) With new management also came a new philosophy. Small-town theatregoers in general, and patrons of the Lyceum in particular, should be able to see the best pictures in a timely manner, right down the street.

Schedler had an original partner in business who left, and in 1976, he was joined in operating the theatre by Nelson Frank. In addition to the aforementioned renovations, the theatre had obtained a shiny new pair of Cinemascope lenses. It was back to operating seven days a week, up from three at the time of Schedler’s takeover. Ownership expressed confidence about the staying power of the movie theatre. Schedler, when interviewed, thought that people had grown tired of low-quality TV movies and that theatres offered something unique. After all, “[w]here would you go on a date?” (xvi) As a pair, Schedler and Frank also founded the Wingham Film and Nostalgia Festival, the first of which was held in 1977. In 1979, the theatre employed five additional staff members: projectionist Ward Robertson, his wife Patti, Rhonda Frank, and Lisa and Jane Vath.

In August 1981, the Lyceum was purchased by the Robertsons. At the time, Ward Robertson had already been employed seven years at the theatre as the projectionist, assistant manager, and maintenance man. When the couple was interviewed, they hoped to enforce smoking rules, install a new heating system, give the lobby a facelift, and were contemplating a new outdoor window for the ticket booth.

The eighties and nineties came with their own sets of challenges to keeping the theatre open. While in the fifties the worry was TV, there was now VHS and home movies to compete with—would patrons want to see films in theatres when they could view the exact same ones at home? An additional factor was increased mobility of local youths, who could now see pictures elsewhere before the Lyceum got hold of them.

Dale Edgar purchased the Lyceum in 1993 and would prove to be its final owner. He would operate it for 12 years until its closure in 2005. At the time, it was Huron County’s longest-running movie house. (xvii)

Sources

i “Lyceum Theatre was Huron’s longest continuous running movie house”, Clinton News Record, David Yates, Jan. 6, 2021

ii “Lyceum Theatre was Huron’s longest continuous running movie house”, Clinton News Record, David Yates, Jan. 6, 2021

iii The Wingham Advance, Dec. 1, 1921, Pg. 1

iv The Wingham Advance, June 14, 1923, Pg. 1

v “The Big Steel Steamer Greyhound”, Goderich Signal-Star, David Yates, April 25, 2024.

vi The Wingham Advance-Times, Oct. 3, 1929, Pg. 7

vii The Wingham Advance-Times, Nov. 28, 1946, Pg. 1

viii The Wingham Advance-Times, Dec. 22, 1948, Pg. 9

ix The Wingham Advance-Times, Oct. 20, 1954, Pg. 1

x The Wingham Advance-Times, Feb. 29, 1956, Pg. 2

xi The Wingham Advance-Times, Oct. 5, 1960, Pg. 2

xii “Lyceum Theatre was Huron’s longest continuous running movie house”, Clinton News Record, David Yates, Jan. 6, 2021

xiii The Wingham Advance-Times, April 4, 1963, Pg. 11

xiv The Wingham Advance-Times, May 5, 1966, Pg. 9

xv The Wingham Advance-Times, Jan. 5, 1975, Pg. 24

xvi The Wingham Advance-Times, Jan. 1, 1979, Pg. 7

xvii “Lyceum Theatre was Huron’s longest continuous running movie house”, Clinton News Record, David Yates, Jan. 6, 2021