by Amy Zoethout | Jun 29, 2021 | Blog, Image highlights, Media Releases/Announcements

Livia Picado Swan, Huron County Archives assistant, is working on the Henderson Collection this summer.

Thanks to a grant from the Young Canada Works Heritage Programme, The Digitized Henderson Gallery is getting a new home! The original photographs, digitized by former staff member Emily Beliveau and funded by the Government of Ontario, will be moved to a website that can be continuously edited by museum staff, making it easier to update information about the photos as we learn more about them. We will also be adding upwards of 600 photos to the online gallery that have never been shared before!

A992.0003.281- Commandos at Sky Harbour, 1943

The gallery displays photographs taken by J. Gordon Henderson, a Goderich-based photographer who documented the classes and airmen at some of the Huron County’s Royal Air Force bases. The collection has more than just portraits, however. Throughout the summer, I will be sharing some interesting finds as I go through the 600 photographs that are yet to be digitized and posted to the gallery. Some of the training activities, weddings and celebrations at the bases have been documented, and give us a peek into the experiences of these airmen and their families.

To take a look at the website, visit https://kiosk.huroncounty.ca/exhibits/henderson-digitization-project/ . Keep in mind that the website is still in development and will continue to be updated throughout the summer. I can’t wait to share some interesting photos and stories with you all!

by Amy Zoethout | Jun 23, 2021 | Blog, Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

Kyra Lewis, Huron Historic Gaol outreach and engagement assistant, explores how the Gaol dodged demolition.

Construction of the Huron Gaol began in 1839 in the Town of Goderich making it Huron County’s first municipal building. This once essential government building served as both a prison and a courthouse once its construction was completed, with the first documented prisoner committed on Dec. 3, 1841. The Gaol held significant value to the people of Huron County, as it represented their newfound independence from London District. The Gaol served as a focal point of justice and was where the Huron District Council held its first meeting on Feb. 8, 1842.

As time went on, the Gaol’s role began to shift; when the new courthouse was constructed in the centre of Market Square Goderich, in 1856, the Gaol’s sole purpose became holding prisoners. However, not all residents of the Gaol were criminals. Many who stayed at the Gaol were homeless, or mentally or physically ill. Drunkards, thieves, debtors and murderers lived alongside the homeless, and children as young as nine years old before Huron County Council constructed a House of Refuge in 1895. As time went on, numbers began to dwindle in the Gaol.

In 1968, The Children’s Aid Society moved into the Governor’s house after the last Governor moved out in 1967. The organization had outgrown their previously occupied space in the basement of the Courthouse located downtown Goderich. During the Children’s Aid Society’s time in the Governor’s house, they witnessed the closure of the Gaol in 1972 after the final prisoner was transferred out. However, prior to the Gaol even being closed as a facility, there was a proposal presented to the Huron County Council in September, 1971, to remove two of the Gaol’s walls adjacent to Napier Street to build a parking lot to accommodate the expanding services of the Children’s Aid Society and the Gaol’s neighbour, the Huron-Perth Regional Assessment Office. On Nov. 26, 1971, County Council received a formal approval from the Provincial Department for the demolition of certain walls at the County Gaol.

This decision provoked a massive response from the community and press, especially from Goderich and the surrounding areas. Many articles began appearing in the local newspapers concerning the possible preservation of the facility, as well as public rejection of the decision to tear the Gaol walls down.

Editorial as published in the Exeter Times-Advocate, Nov. 25, 1971

The papers referred to the old facility as an “underdeveloped historical attraction”, and “a real drawing card for a growing tourist industry”. However, Council at the time had no intention of utilizing the space as a Museum of Penology. Some councillors did not condone the county spending the money to restore the building, as it was projected the restoration would cost around $25,000. Other councillors believed that if they had that much money to spend, it should be allocated around the county, and not just in Goderich. Another drawback that was suggested was the glorification of previous inmates whose actions were heavily frowned upon. The potential of immortalizing the darker aspects of Huron County’s past was a genuine concern amongst officials.

The Property Committee eventually presented the County Council with another report on Dec. 8, 1972, which detailed the idea of the old Gaol becoming a “Museum of Penology”. However, in the same report they also put forth a recommendation to construct a parking lot and an extension for the Assessment Office, costing a projected $150,000. In January, 1973, Huron County Council approved the removal of three walls at the Gaol, after considering both the Children’s Aid office and the Assessment Office’s needs. The Gaol was unfortunately placed back on the chopping block, now set to lose another wall.

When citizens caught wind of the verdict, they were none too pleased with the potential defacement of such an iconic local building. More articles and letters to the editor began showing up in the papers and a small group of concerned citizens came together to fight to save the historic building. If the Gaol walls were to be torn down, it would completely ruin the integrity of the building’s design. As the Gaol’s architect, Toronto-born Thomas Young had been inspired by famed English philosopher and prison reformist Jeremy Bentham. Thus, the loss of the Gaol walls would compromise both the value and history of the structure, as they added an irreplaceable element to the significance of its layout and design. The goal of this growing group of local politicians, historians and volunteers was to pressure the Council into reassessing their decision to tear down the walls. Their arguments were intended to bring to light the necessity of the architectural, historical and cultural conservancy of the building. And so, the Save the Jail Society was born!

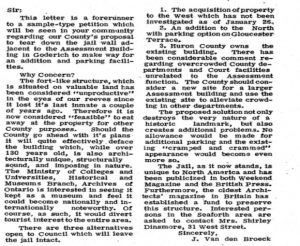

Letter to the Editor written by Joan Van den Broeck published in the Goderich Signal-Star.

With their objectives set, the group of dedicated members wrote letters to the newspaper, educating the public on their cause. A brilliant letter addressed to the editor of the Goderich Signal-Star was written by Save the Jail Society activist Mrs. Joan Van den Broeck. She advocated for the preservation of the Gaol, stating the uniqueness of the architecture as being one-of-a-kind, as well as miraculously structurally sound despite being around 130 years old, predating confederation. She also spoke of the building’s national and international notoriety, which would only enhance the tourist experience in Huron County. Van den Broeck, along with Goderich Reeve Paul Carroll and their fellow Save the Jail Society members, sought to change the fate of the iconic building.

The Save the Jail Society was extremely vocal and visible within the community, organizing campaigns at Goderich District Collegiate Institute and compiling a petition, as well as fundraising and rallies. There was a song written to commemorate the Gaol, which was written by Wingham entertainer Earl Heywood. The song was sung to the tune of Battle Hymn of the Republic, and was sung at events and rallies. They presented a petition to Huron County Council, as well as an architect’s revised plan for the parking lot to be built on the north side of the building. The group also threatened to pursue legal action if the demolition was to move forward.

One of the group’s most engaging events was an open house held at the Gaol on Feb. 19, 1973, which was initiated to motivate and engage the community in the cause to save the building. This event amassed a crowd of over 2,000 people who were all curious to explore the historic building and to find out what the big deal was about the Gaol. This event is what Save the Jail Society members would later reflect upon as a tide turner in terms of popular support. This event also made a massive impression from County Council’s perspective, as they were now aware of the appreciation the community held for the building.

Goderich Town Council met on April 12, 1973, in response to a letter issued from the County. This letter was a revision of the previous parking lot proposal designed by Nick Hill, which would allow for the Gaol walls to remain untouched. Finally, on April 26, 1973, Huron County Council agreed to the proposal by Goderich Town Council. This acceptance meant that the Save the Jail Society’s goal of saving the Gaol had been realized!

Once the safety of the Gaol had been ensured, the Save the Jail Society began to create an administration to govern the historic building. On May 1, 1974, the “Huron Historic Jail Board” was created. The Jail Board leased the building from the County for $1 per year for it to be incorporated as a Museum and Cultural Centre; it was opened to the public on June 29, 1974. The Jail board was finally legally incorporated on Oct. 13 of the same year. The Gaol was finally a Museum of Penology!

This great victory for the Save the Jail Society (now the Jail Board), was only the beginning for the Huron Gaol. On July 5, 1975, a massive celebration was held at the Gaol in Goderich to acknowledge the Gaol becoming designated a National Historic Site. The ribbon was cut to officially acknowledge the opening of the Huron Historic Gaol by Huron County Warden Mr. A. McKinley. The plaque detailing the Gaol’s historical significance was unveiled by none other than dedicated member Joan Van den Broeck.

This great victory for the Save the Jail Society (now the Jail Board), was only the beginning for the Huron Gaol. On July 5, 1975, a massive celebration was held at the Gaol in Goderich to acknowledge the Gaol becoming designated a National Historic Site. The ribbon was cut to officially acknowledge the opening of the Huron Historic Gaol by Huron County Warden Mr. A. McKinley. The plaque detailing the Gaol’s historical significance was unveiled by none other than dedicated member Joan Van den Broeck.

The reason the Huron Historic Gaol stands to this day is not simply because of its historical value. This building is a symbol of the strength and dedication of the people of Huron County. Despite being sentenced to be destroyed, the Gaol was saved by the efforts of ordinary Huron County citizens who fought to preserve their history. The Gaol is not only a building which represents law and order within the County, but a reminder of how the County was incorporated and achieved its own independent settler municipal government and identity. Huron County was created by strength and unity, it seems only fitting its history was also saved by it.

Sources

Explore these sources through the online collection of Huron Historic Newspaper.

- “Jail an Attraction?”, The Exeter Times-Advocate, Nov. 25, 1971, pg 4.

- “Save Jail Wall”, The Brussels Post, Jan. 31, 1973.

- “And the Walls Came Down…Maybe”, The Exeter Times-Advocate, Feb. 8, 1972, pg 4.

- “Huron Council Clears Removal of Jail Wall”, The Huron Expositor, March 1, 1973, pg 1.

- “Letters to the Editor by Mrs. D. W. Collier Komoka”, Clinton News Record, March 15, 1973, pg 7.

- The Huron Expositor, April 12, 1973, pg 19.

- “Huron Reeves Vote to Save”, The Brussels Post, May 2, 1973, pg 9.

- “At County Council: Reeves Vote to Preserve Huron’s Historic Jail”, The Huron Expositor, May 3, 1973. Pg 1.

- “Jail House Blues Still Bother County”, Clinton News Record, June 7, 1973, pg 3.

- “Reeves Reject Bid for Use of Huron County Jail”, The Brussels Post, July 4, 1973, pg 13.

- “Tenders Let for Office”, The Blyth Standard, July 18, 1973, pg 1.

- “The Huron Gaol”, The Huron Expositor, June 1, 1978, pg 13.

Archival Material

- “Commemoration of Huron County Gaol”, July 5, 1975, pg 1-2.

by Amy Zoethout | May 20, 2021 | Blog, Collection highlights

Take a closer look at the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol and its collections as staff share stories about some well-known and some not-so-well-known features, artifacts, and more. In the last of a three-part series, Registrar Patti Lamb takes a closer look at deaccessioning artifacts from the Museum’s collection. Read Part 1 on Museum’s Secret Codes and Part 2 on Collecting at the Huron County Museum.

The Collection at the Huron County Museum is quite large and began with the collection of Joseph Herbert (Herbie) Neill. When Mr. Neill opened the Huron County Pioneer Museum, he brought his own collection and many people continued to donate more items regularly to the Museum. The Museum has actively been collecting artifacts since 1951. In the early days, the collections mandate was greater and objects came into the Collection from all over Ontario and in some cases other parts of Canada. Since that time, there has been an increase in the number of County and Municipal museums, as well as independent museums with specific collections focus.

Presently, many museums are focusing on refining their collections. Previous collecting without a mandate has resulted in museums having a lack of storage space, overcrowding, and items outside of their current mandates. Museums have been encouraged to have a Collections Policy and Collecting Mandate. In the case of the Huron County Museum, items coming into the Collection must have historical relevance to Huron County. Part of the Collections Policy must also be a policy on deaccessioning.

Deaccessioning is the process to officially remove an item from the listed holdings of a museum. It is never taken lightly and has very strict policies and procedures associated with it. Rules and regulations from the Ontario Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture, as well as County and Museum policies must all be adhered to. The Huron County Museum has actively started to look at deaccessioning as a way to refine the Collection to be more clearly Huron County focused and to make the best use of current storage space.

These uniforms were recently deaccessioned from the Museum’s collection and transferred to the Bruce County Museum, as they were worn by Captain Shirley M. Robinson CD, from Kinloss Township, who was a Nursing Sister in the Canadian Forces.

The two main factors for deaccession are non-Huron County relevance or condition. If while searching the database, we find an artifact that was manufactured or used somewhere other than Huron County it could be considered for deaccession. However, place of manufacture is not the only factor. For example, a plow or coat that was manufactured somewhere else but was used to plow the fields for 40 years in Colborne Township, or worn by a women from Exeter on her wedding day, makes it relevant to Huron County. If an artifact is in poor condition, and as such could cause damage to other artifacts or effect the safety of staff and visitors, it would also be considered for deaccession. Mr. Neill’s original collection would not be included in the deaccession process.

Occasionally, the Museum will be offered an artifact that has a strong story or provenance but is similar to several others already in the Collection. In this case, the Registrar will do research into the Collection by searching the database and files to find out the relevance of the other similar objects. If there are similar objects with no history, relevance, or in poor condition they may be considered for deaccession making room for the new object.

Once an object has been identified for potential deaccession, the Registrar will prepare a report to be presented to the Huron County Museum Collections Committee. This report includes any known information about the artifact and reasons why it should be deaccessioned. If the Collections Committee also finds that the artifact should be deaccessioned, the report is forwarded to County Council for approval. If County Council approves, then the deaccessioning process can begin. The object will then go through the following options until the appropriate one is found:

- Transferred to the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol “hands on” educational collection.

- Offered as an exchange, gift or private sale to other public museums, or similar public institutions.

- In the event that the artifact is not disposed of to the Canadian museum community, it may be deaccessioned through public sale. All monies obtained through the sale of deaccessioned objects will be used only for collection acquisition and care.

- As a final option, the artifact will undergo intentional destruction before witnesses by designated museum personnel or disposed of in a fashion (such as to a scrap metal dealer) which ensures it cannot be reconstructed in any way.

Signed paperwork and photographic documentation for all the above options is required and added to the object record. In most cases, option number two is the one that is used. The Registrar contacts the appropriate museum in the area that is most relevant to the object to discuss the transfer of the object. Since 2013 to the end of 2020, 439 objects have been transferred to other museums or institutions, returning them to the geographical areas where they truly belong and thus allowing the local residents and tourists of the area to enjoy, learn, and discover them.

This Fire Hose Reel was deaccessioned and transferred to Lambton Heritage Museum. It was used at Imperial Oil Refinery at Sarnia in 1892.

by Amy Zoethout | May 19, 2021 | Blog, Collection highlights

Take a closer look at the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol and its collections as staff share stories about some well-known and some not-so-well-known features, artifacts, and more. In the second of a three-part series, Registrar Patti Lamb takes a closer look at the Museum’s collections and the process of accepting and cataloguing donations into the collection. Read Part 1 on Museum’s Secret Codes and Part 3 on Deaccessioning Artifacts.

Visitors and members of the general public are often curious as to what happens behind the scenes at the Huron County Museum. Questions commonly asked to the staff are: what happens to the “stuff” once it’s donated; what does the collections staff do; where does the museum put all the “stuff”; and what happens when the museum is done with it? These are all really good questions and this blog is an attempt to share the different roles of the Collections staff and what happens when someone has donated something to the Museum.

Museum Technician Heid Zoethout, Registrar Patti Lamb, and Archivist Michael Molnar are three of the primary roles within the Museum’s Collections staff.

A Collections Team

There are three primary roles within the Collections staff. They are the Archivist, Museum Technician, and Registrar. Each role works separately within their own individual job descriptions but they all work together as a team.

The Archivist is responsible for the archival collection which includes all paper based, 2 dimensional items such as photographs, documents, diaries, and minute books. The Archivist processes donor forms; documents and catalogues the donations of archival material; and conducts research for or assists with research for others.

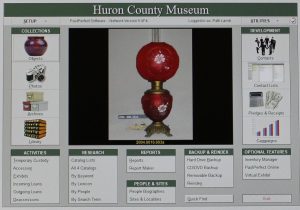

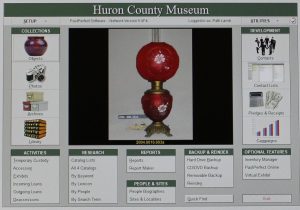

PastPerfect is the Museum’s Collections Management System

The Museum Technician is responsible for the housing and location of the artifacts. The Technician makes sure the artifacts are stored properly; are safely handled and displayed in ways that are not damaging; and locates the artifacts in the museum buildings and the collections database. This role also monitors temperature, humidity, and light levels.

The Registrar looks after the documentation of donations of three-dimensional objects; processes donor forms; catalogues the artifacts to include detailed descriptions and provenance; photographs the artifacts; and maintains PastPerfect, the Museum’s Collection Management Software. This role also looks after the documentation of incoming and outgoing loans as well as conducts research on objects in the Collection.

How to Donate to the Collection

When someone is interested in making a donation to the Huron County Museum, they need to contact the Archivist for archival material, or the Registrar for three-dimensional objects. This blog is going to focus on three-dimensional object donations, but the process is basically the same for archival material. Anything being considered for donation to the Museum must meet the collections mandate or criteria. Items must have historical relevance to Huron County, meaning they must have been used or manufactured in Huron County, or have a significant provenance (history) that ties them to the County. Artifacts should also be in good condition.

Once contacted to inquire about donating items, the Registrar will chat, either by phone or email, with the potential donor to determine the relevance of the items. Usually the donor will be asked to email some photographs of the object(s) so the condition can be determined and to make clear what the object is they wish to donate. Most times the donor will not be given an acceptance or denial answer right away. The Registrar wants to look at the potential donation, and take some time to do a search in the database to see if there are duplicate items such as the ones that are being offered. If the Museum does have several similar items, it needs to be determined if the ones in the Collection have a detailed story or history associated with them or if the new item would tell a better story.

Once it has been determined that the artifact will be accepted into the Collection, an appointment is made between the Registrar and the donor to bring the item to the Museum. At that appointment, gift forms (donor forms) are prepared by the Registrar for both the donor and Registrar to sign. Included on the form is the donor’s name, address, and contact information; item(s); and a detailed history (provenance) about the item. Information also includes where, when, and how it was used; by whom it was used; and how the donor came to have it.

By signing the donor form, the donor is stating that they have the legal right to the item and can therefore sign ownership over to the Museum. Once the form is signed, the artifact becomes the legal property of the Museum. If the donor wants an income tax receipt for their donation a further step will be taken. Prior to the appointment, the donor must obtain a written appraisal of the artifact. The appraisal must be on the letterhead of the appraiser or antiques dealer and accompany the donor to the appointment. The appraisal is given to the Registrar with the artifact and once the gift forms are signed, an income tax receipt will later be prepared and mailed to the donor.

Photographing an artifact is the last step in the cataloguing process.

Cataloguing the Donation

When the paperwork is complete, the cataloguing process can begin. Cataloguing an artifact includes assigning an object ID number and documenting as much information as possible about the object. A detailed description is required describing all the physical attributes of the item such as measurements, colour, material makeup, condition, and functionality. The record will also include how, where, and when the object was used. Often research is involved to discover important facts regarding the object, the family that used it, or the business from where it came. The history of an object is just as important as the object itself. For example, a quilt is just a quilt, but a quilt with a good description and detail about why it was made, who made it, who used it, and where it was used makes it much more interesting and relatable.

An object ID number is then added to the object in a way that does not damage the artifact. Textiles will have a cloth label sewn onto them and objects with harder surfaces have a number added that is removable should it need to be.

The last step in the cataloguing process is photography. Each object is photographed in detail showing all sides, close ups of significant or interesting parts, and any condition issues such as cracks or peeling paint. Photographs are then added to the record in the database and ultimately uploaded with the record to the Online Collection, which features over 6,000 artifacts from the Museum’s collection.

When the object is completely catalogued, it is placed in a temporary location in the main storage area for the Museum Technician to then find it a permanent home. The permanent location is documented in the database so the artifact is accessible to go on exhibit or loan, or be used in research when needed.

by Amy Zoethout | May 18, 2021 | Blog

Take a closer look at the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol and its collections as staff share stories about some well-known and some not-so-well-known features, artifacts, and more. In a three-part series, Registrar Patti Lamb takes a closer look at a museum’s secret codes. Read Part 2 on Collecting at the Huron County Museum and Part 3 on Deaccessioning Artifacts.

The Object Identification Number is an important part of the “secret language” used by museum professionals.

Most museum visitors are aware that the artifacts in the museum have numbers written on them. Most also know that the numbers somehow help to identify the objects. What most don’t realize, however, is what the numbers mean to the museum staff.

When museum staff look at an Object Identification Number (object ID), they can instantly tell what year the object came to the museum; if there were other objects that came in before it that particular year; whether it was part of a group of objects; and in some cases, whether or not there is a known donor. Using an object ID number to look up an object record in the museum database will show the staff everything that is known about the object. This includes physical description, donor, provenance (history), condition, use, and where in the museum the object is located.

Traditionally, museums use a three part numbering system. The first part lets staff know the year the artifact came into the museum collection; the second part indicates the group number of the artifacts that came in during a particular year; and the last number is the object number within that group. The first two parts of the number are what is known as an accession number (an object or group of objects from a single source at one time). When the third part of the number is added on, it becomes an object ID number specific to that object.

Accession and object ID numbers are an important part of the “secret language” used by museum professionals. They allow us to record and store, in one spot, important information about the artifacts as well as help track and locate them. The object ID is as important as the artifact, and without it, access to the information about the artifact would be difficult to retain and retrieve.

Object Identification Number shown on this Museum artifact.

by Amy Zoethout | Apr 7, 2021 | Archives, Blog

Take a closer look at the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol and its collections as staff share stories about some well-known and some not-so-well-known features, artifacts, and more. Archivist Michael Molnar looks at the Land Registry Copy Books available through the Huron County Museum’s Archives that can help with family research.

Did you know that the Huron County Museum has Land Registry Copy Books for the County of Huron?

Land Registry Copy Books contain historical (1835 – 1950s) information about the transactions of real property (specifically the ownership of land). These recorded transactions can be one way of confirming the existence of your ancestors in Huron County – confirming is a very important and rewarding step when conducting family research.

These historical Land Registry Copy Books are housed in the archival stacks at the Huron County Museum and can be accessed by appointment with the Archivist. While the Museum is temporarily closed to the public, learn more about the Archives’ new virtual research services here: https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/huron-county-archives/

You can find information in the Land Registry Copy Books about your ancestors if you know a lot and concession number (rural) or a lot number (urban). You can access an historical map of Huron County with names and lot and concession numbers here: https://digital.library.mcgill.ca/countyatlas/huron.htm. This map can be a great starting point.

The Land Registry Copy Books housed at the Huron County Museum include information for the following communities:

Former Townships of Huron County: Ashfield, Colborne, East Wawanosh, Goderich, Grey, Hay, Howick, Hullett, McKillop, Morris, Stanley, Stephen, Tuckersmith, Turnberry, Usborne, and West Wawanosh.

Towns and Villages: Bayfield, Bluevale, Blyth, Cranbrook, Crediton, Dashwood, Dungannon, Ethel, Exeter, Fordwich, Goderich, Hensall, Kinburn, Lakelet, Lucknow, Manchester (Auburn), Nile, Port Albert, Seaforth, St. Joseph, Summerhill, Varna, Walton, Wroxeter and Zurich (not an exhaustive list).

You can access online historical land registry information for properties in Ontario through OnLand: https://help.onland.ca/en/what-is-onland/