Huron’s Unheard Histories: Searching for Grey Township’s Black Pioneers

What’s your journey to Huron County? This spring, visitors to the Huron County Museum can follow the journeys of seven families across the globe and through time in Stories of Immigration and Migration, a temporary exhibit dedicated to tales of settling in Huron County. The exhibit traces the circumstances that caused individuals within Canada and across the world to leave their former homes, as well as the migrants’ experiences building new lives in Huron. With Stories set to open on April 5th, researcher Sinead Cox shares why the journeys of some Huron County families are more difficult to research than others:

Museum staff are looking forward to shedding light on local histories that have never been featured in our galleries before with Stories of Immigration and Migration, an exhibit which spans a period from 1840 to the present day. When research started several months ago, I had the pleasure and privilege of speaking or corresponding directly with the more recent ‘migrants’ featured in the exhibit, and the opportunity to include their own words, insights and chosen artefacts. For those individuals who arrived more than a century ago, however, our research relied on archival records that often uncovered as many questions as answers.

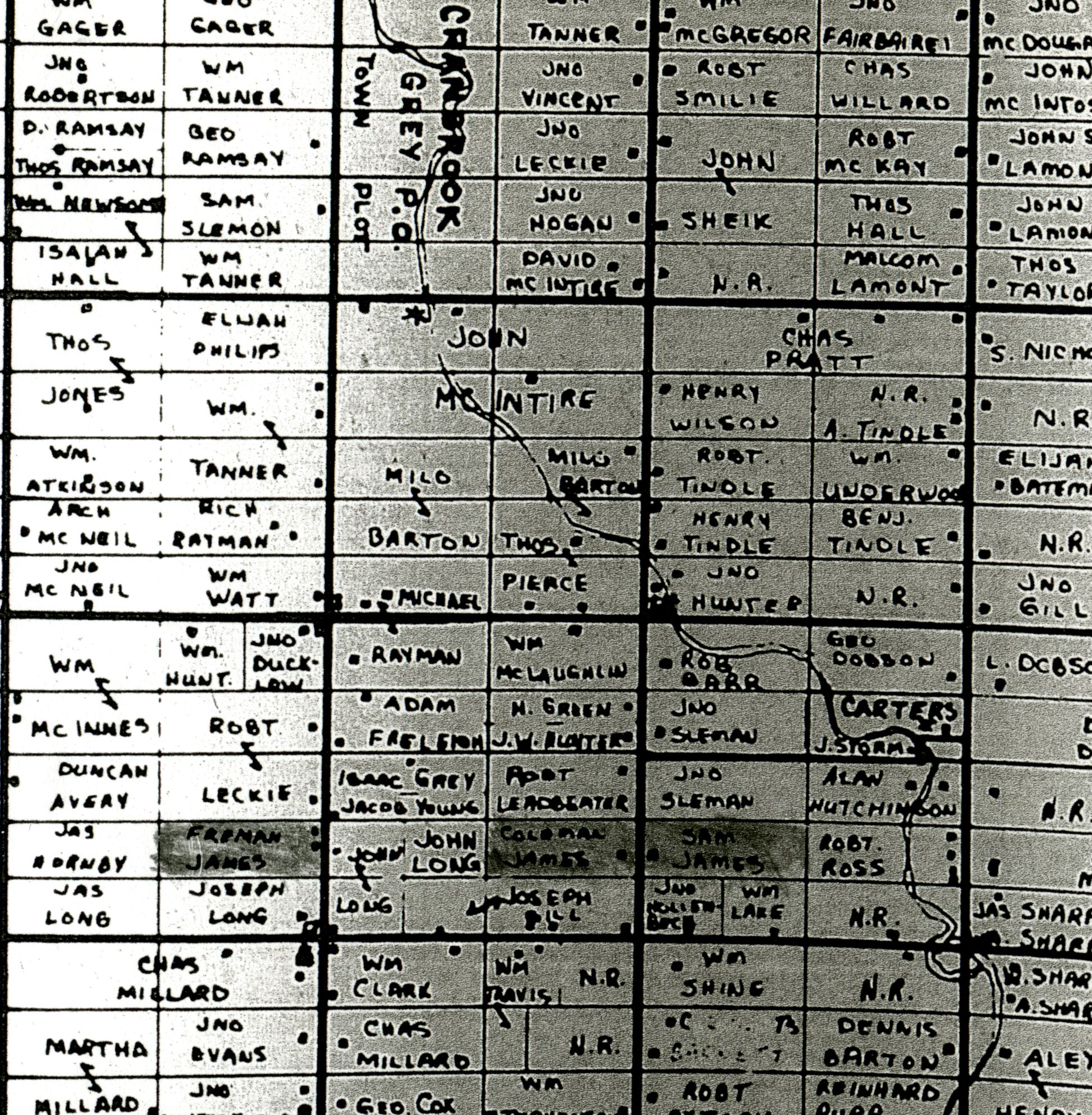

One compelling story that remains incomplete is that of Samuel and Mary Catherine James, a Black farming couple born in Nova Scotia who were some of the earliest settlers in Grey Township circa the 1850s. Nova Scotia was a destination for many former slaves from the colonial United States, including loyalists who had served the British crown during the American Revolution, in the eighteenth century. The James family also lived in Peel, Wellington County, before settling in Grey–which was part of the “Queen’s Bush” territory, rather than the Huron Tract lands managed by the Canada Company. Since the Jameses were farmers, they probably came to Huron County to achieve the same objective as most other pioneers: to own land. The James clan, including children Freeman, Coleman, Magdalene and Colin, farmed in a row on Lots 24 of Concessions 9, 10 and 12, Grey Township. According to 1861 census records, the whole family lived together in the same log house when they first moved to Huron.

Tragedy struck the James family when, in a matter of only three months–between November 1866 and January 1867–Colin (aged 23), Freeman (aged 39), and Mary Catherine (aged 77) all died. Whether their passings were related or coincidental, this unimaginable loss must have been a devastating blow to a pioneer family that relied on family members to share the burden of work. Mother and sons are buried at Knox Presbyterian Cemetery, Cranbrook.

According to land registry records, Freeman’s farm at Lot 24, Concession 12, still not purchased from the crown at the time of his death, was taken over by his sister Magdalene “Laney” James’ husband, Charles Done. Charles was also a Black farmer from Nova Scotia, and living in Howick when he married Laney at Ainleyville (now Brussels) on November 4th, 1867.

Laney and Coleman, the two surviving James siblings, each raised large families in Grey Township. In the 1871 census, Coleman and his wife, Lucy Scipio, already had eight children, five of them attending school. According to the same census, both Coleman and Laney could read and write, but their spouses could not. The family was struck by tragedy once again in April, 1873 when Coleman’s nine-year-old son, also named Coleman, died of “inflammation of [the] liver” after an illness of nine months.

Coleman sold his farms in 1875, and by the 1881 Canadian census, both he and Laney had left Huron County and relocated to Raleigh, Kent County with their families. This move to Raleigh would have enabled the James siblings to join a larger Black community at Buxton: a settlement founded by refugees that came to Canada through the Underground Railway.

The James family had relocated many times: according to tombstone transcriptions, Mary Catherine was born in Shelburne, Nova Scotia, and Colin in Digby, before the family moved to Ontario and lived in Wellington County, Huron County, and Kent. Census, birth and death records indicate that Coleman’s children ultimately settled in Michigan. Most farm families in nineteenth-century Ontario moved in search of the same benefits: a supportive community life, the ability to make a living, and good agricultural land. Black farmers, however, faced barriers of discrimination and exclusion that white settlers did not, and this sometimes necessitated leaving years of hard work behind to repeatedly seek a better life elsewhere.

It’s that moving on that can make traces of Huron County’s early Black settlers difficult to find in history books or public commemorations. The collections at the Huron County Museum, for example, are entirely acquired through donations from the community, which tends to emphasize the experiences of families that stayed here, found success, and had descendants who retain ties to the county to this day. We know less about the settlers who moved out of the county-even those who lived in Huron for decades, like the Jameses– and thus we also lack clarity about the opportunities they sought elsewhere, or the specific challenges they may have faced here.

The details I could glean from a few days’ of research did not provide enough information to interpret why the James family came to Huron County–or why they left–for Migration Stories. But I hope future research opportunities will add to this initial knowledge, and to a better understanding of the contributions and experiences of the individuals who have moved in and out of Huron County, including Black pioneers like the James family.

Special thanks to Reg Thompson, research librarian at the Huron County Library, for starting and contributing to the research used for this piece. If you have information about the James family and would like to share, contact Sinead, exhibit researcher: sicox@huroncounty.ca

You can see Stories of Immigration and Migration at the Huron County Museum (110 North Street) from April 5th until October 15th, 2016.

This post was originally published in February and republished in March after technical difficulties with the server.