by Amy Zoethout | Sep 9, 2021 | Archives, Blog, Investigating Huron County History

Kyle Pritchard, Special Project Coordinator for Huron’s digitized newspaper project, examines the types of content newspapers produced and how it changed over time to reflect the needs and demands of a growing community. You can search the newspapers yourself for free at https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers/

In the age before smartphones and flat screens, newspapers served an important role in the functioning of communities. The Huron County Digitized Newspaper Collection began as Project Silas in 2014 to improve access to the enormous volume of local newspaper content previously only available on microfilm and in their physical format. Today, the digitized collection holds over 350,000 newspaper pages, which preserves a century and a half of local history. The papers were scanned and made searchable using OCR (optical character recognition) technology to assist researchers of all kinds to advance our understanding of the history of Huron County. Each of the newspapers in the digitized collection captures a unique vantage point of the past and is an invaluable tool for researchers in topics as wide-ranging as political, social, cultural and genealogical history.

Many newspapers have come and gone from Huron County, and only a handful have modern counterparts which have survived until today. Many publishers shut down, relocated, or merged with other news agencies to stay afloat. Those that lasted did so by pivoting to new audiences and revenue streams to keep the presses printing. By doing so, editors expanded the roster of sections their newspapers offered to retain their relevance and competitiveness.

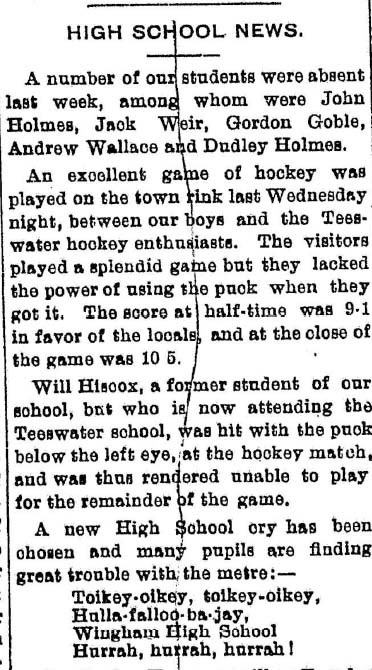

High School News published in the Wingham Times, Feb. 11, 1909.

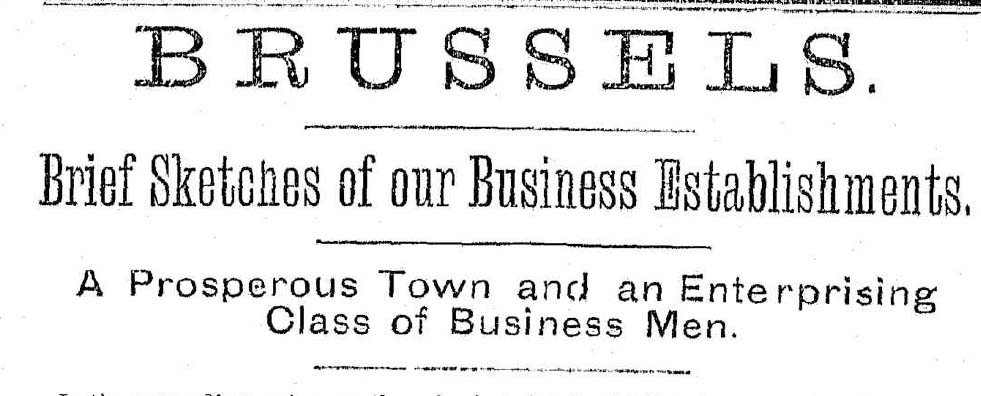

Local newspapers strove to build a sense of communal identity. Farmers and merchants relied on newspapers extensively for everything from rural news, to exhibition schedules, to weather forecasts. Business was so central to early newspapers that a review of local businessmen and their storefronts in the Brussels Post in 1893 filled the entire front page. (Brussels Post, Oct. 20, 1893, pg. 1). The personals column documented locals’ travel arrangements in and out of the county and informed them of visitors returning home. A defense of personals columns was reprinted in the Clinton News Record from the Listowel Banner after the editor received complaints that “they are silly and that they are not read.” They responded by referring to the personals in their own paper as being “one of the most interesting developments in modern journalism,” (Clinton News Record, Aug. 8, 1935, pg. 3).

By the turn of the 20th century, sections on politics, business and industry within newspapers were condensed to increase the space available for larger advertisements and new columns. This trend increased as newspaper readership grew more slowly over the course of the world wars with competition from radio and television. In response, editors endeavored to expand the reach of their newspapers to new audiences. Fashion, recipe and lifestyle sections were introduced in hopes of appealing to women, and cartoons and high school news were aimed at stimulating the interest and involvement of young people. Readers who perused The Seaforth News in 1962 could discover the new culinary marvel of pancake houses which were taking the United States by storm and try their hand at “African banana pancakes” and “New Orleans kabob hot cakes”. (The Seaforth News, March 22, 1962, pg. 2) Or, depending on the decade, they might serve their families an unsavory recipe for depression-era oyster stuffing. (The Wingham Advance-Times, Dec. 19, 1935, pg. 7) Just like readers in the past, these kinds of recipes are preserved today in the digitized newspapers just waiting for savvy or unsuspecting chefs to test them out in their own kitchens.

Newspapers were also an important medium for local teens to keep a record of events, communicate, and share high school gossip. Yet, it might be surprising to know that the oldest high school news column in Huron County started in 1909 in the Wingham Times. It was not really until after the Second World War that young people really established a presence in news reporting. (Wingham Times, Feb. 11, 1909, pg. 1) Introduced to fill some of the space left by wartime commentary, high school journalism was forward-thinking and allowed the opportunity for newspapers to attract and engage with a younger audience. The results of games played by local sports teams and club activities were a major highlight of these sections, which eventually came to fill a whole sheet in the newspaper. (Lucknow Sentinel, Dec. 18, 1947, pg. 3)

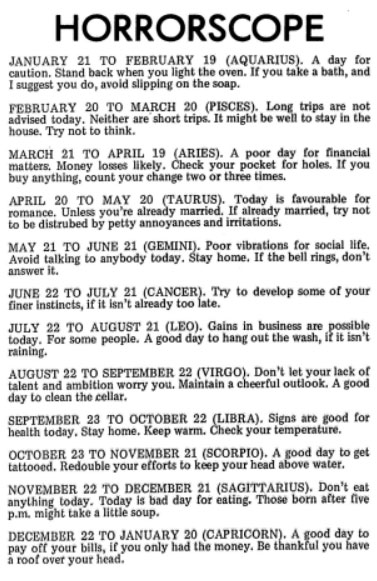

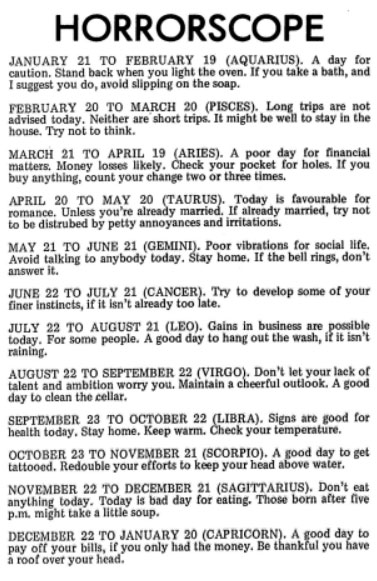

The Horrorscope as published in the Exeter Times-Advocate, Oct. 23, 1969.

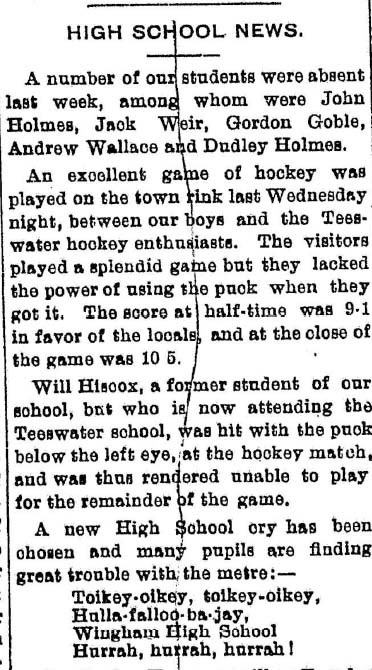

Even small editorial changes which found room for community announcements, movie showtimes, advice columns and crossword puzzles were intended to position local news so that papers provided little bouts of day-to-day wisdom, small-town gossip and casual distraction. In an October edition of the Exeter Times-Advocate published in 1969, readers were treated to a horrorscope, an inverted horoscope which only offered bad advice. Pisces were told that “Long trips are not advised today. Neither are short trips. It might be well to stay in the house. Try not to think,” whereas Capricorns were reminded it was “A good day to pay off your bills, if you only had the money. Be thankful you have a roof over your head,” (Exeter Times-Advocate, Oct. 23, 1969, pg. 9)

Even small editorial changes which found room for community announcements, movie showtimes, advice columns and crossword puzzles were intended to position local news so that papers provided little bouts of day-to-day wisdom, small-town gossip and casual distraction. In an October edition of the Exeter Times-Advocate published in 1969, readers were treated to a horrorscope, an inverted horoscope which only offered bad advice. Pisces were told that “Long trips are not advised today. Neither are short trips. It might be well to stay in the house. Try not to think,” whereas Capricorns were reminded it was “A good day to pay off your bills, if you only had the money. Be thankful you have a roof over your head,” (Exeter Times-Advocate, Oct. 23, 1969, pg. 9)

The Digitized Newspaper collection is constantly expanding to include more local historical content. The database is free, searchable and easy to use. So, what are you waiting for? Whether a traditional, or not so traditional, recipe, a photograph of your high school sports team, or the latest in 1970s fashion, head on over to the Huron County Museum website and start exploring! Who knows what you might find?

by Amy Zoethout | Sep 1, 2021 | Blog

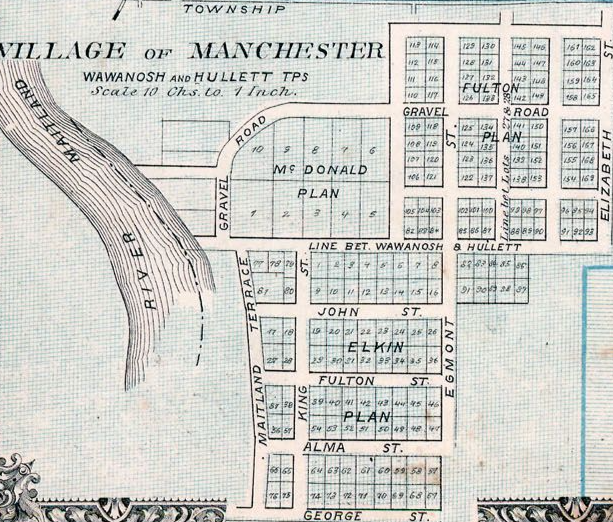

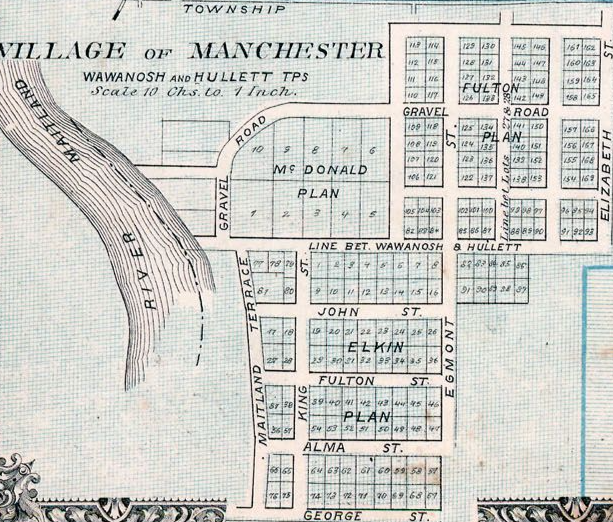

If you’re out touring County Roads this summer, you may notice some new brown and white heritage signs marking Huron County’s historic settlements. The project was initiated by the County’s Public Works Department as a way to remember these communities that once existed in Huron. To date, 23 signs have been erected, including three signs marking communities that still exist, but under a different name. These signs have the word ‘historic’ added to show their historic name, like Manchester, which is still a thriving community now known today as Auburn.This summer, our student Maddy Gilbert will explore the history of some of these settlements.

The Village of Manchester was founded in 1854 on the edge of the Maitland River where the Village of Auburn now sits. It was listed on a map from the 1860s as Manchester, but by 1879, a map of Huron County lists the village as both Manchester and Auburn. As recent as 1979, the official name for the community was the Police Village of Manchester, while Auburn was the name of the post office. But by February 1979, Manchester was no more as the village trustees voted to keep Auburn as the one and only name for the village. Since there was another Manchester located in Ontario, the change came to avoid confusion between the two communities.

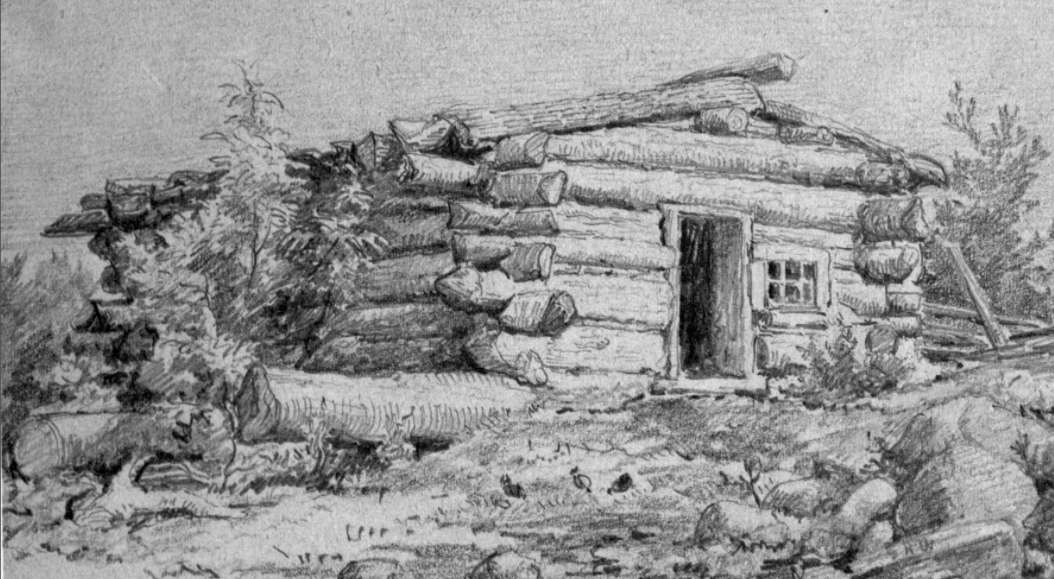

This is an example of a log shanty, much like the one Eneas Elkin would have lived in.

Isabel Elkin, wife of Eneas Elkin

Eneas Elkin was the first settler to Manchester. He walked all the way from the City of Hamilton and built a log shanty. George Elkin, son of Eneas and Isabel Elkin, was the first baby born in Manchester on April 13, 1850. The first wedding in the village was credited to be between Anne (nee McDonald) and Joseph Tewsley. Annie passed away after only one year.

For the first two years after Mrs. Elkin joined her husband Eneas in Manchester, there was only a track between Goderich and Manchester, until the Canada Company opened what is now Huron County Road #25 in 1851. Until a bridge was built, Elkin ran a ferry across the Maitland River. The first two bridges crossing the Maitland were constructed out of wood and washed away in spring floods. The third bridge was constructed partly out of steel, until the concrete bridge was constructed a few yards upstream in 1954.

Eneas Elkin surveyed Hullett Township, which was amalgamated into the Municipality of Central Huron in 2001.

1975 Ink Print of the Auburn Bridge done by Jim Marlatt, a local artist. This bridge was in use until the new, concrete bridge was completed upstream in 1954.

By 1866, Manchester had a flour mill which shipped goods as far as Montreal. There was also a saw mill erected by John Cullis after he purchased the flour mill. The saw mill produced lumber from the logs that were cleared, to be sold as lumber for the barns being erected throughout the area. Cullis’ saw mill was destroyed by fire in 1893, and Cullis rebuilt a short distance away. The second mill was also victim to fire.

The Village had power by 1896 leading to the installation of electric powered street lamps. A.E. Cullis, who ran the grist mill, installed a direct current generator on his property and supplied power from dusk until 11 p.m. at the rate of two cents per light per night. Most villagers kept their costs down by attaching one light to a very long cord that they could move from room to room.

The Auburn CPR Station opened in 1907 with the delivery of a car-load of salt to W.T. Riddell. One delivery was a cow from Bracebridge. The station closed in 1979 and any deliveries made by train for people living in the village would have been left at the Blyth CPR Station.

The first brick bank in Manchester was the Sterling Bank of Canada, which eventually became a CIBC branch. On Nov. 14, 1930, Manchester suffered a terrible fire, which destroyed the hardware store that was located beside the bank. Mr. and Mrs. Carter were the first to notice the fire, and Mrs. Carter ran into the street yelling “fire!”. Mrs. Carter could have been the one who saved the lives of Mr. A.M. Rice and family, who resided above the CIBC, where Mr. Rice was manager.

Today, the Village of Auburn sits southeast of the intersection of Huron County Road 25 (Blyth Road) and Huron County Road 8 (Base Line). Auburn lies 20 km east from Goderich, 20 km north from Clinton, and 10 km west from Blyth.

Sources

Belden, H. “Map of Morris Township.” Illustrated Historical Atlas of the County of Huron, Ont., H. Belden, 1879.

Gropp, Bonnie, editor. “Police Village of Auburn: Settlement of Manchester Grows out of Wilderness.” The Citizen, 29 Dec. 1999. From the Digitized Newspaper collection at the Huron County Museum

Johnston, Tom. The Blyth Standard, 27 June 1979. From the Digitized Newspaper collection at the Huron County Museum

Bradnock, Eleanor. “Manchester No More.” The Blyth Standard, 27 June 1979. From the Digitized Newspaper collection at the Huron County Museum

“Craigs Took Over Sawmill in 46 .” The Blyth Standard, 27 June 1979. From the Digitized Newspaper collection at the Huron County Museum

“Eneas Elkin Walked from Hamilton to Establish Auburn.” The Blyth Standard, 27 June 1979. From the Digitized Newspaper collection at the Huron County Museum

“Isabel Elkin.” The Blyth Standard, 1979. From the Digitized Newspaper collection at the Huron County Museum

by Amy Zoethout | Aug 16, 2021 | Archives, Blog

Livia Picado Swan, Huron County Archives assistant, is working on the Henderson Collection this summer and highlighting some of the stories and images from the collection.

In keeping with our August theme of making lemonade from lemons, we take a look at some of the wedding photos taken by Gordon J. Henderson during the Second World War. The photographs highlight some of the men and women of the Royal Canadian Air Force who celebrated their marriages while stationed at one of Huron County’s air training schools. So far, staff know of 18 different weddings that Henderson photographed, which are all available to be viewed online.

During the Second World War, Henderson, travelled to air training schools in Goderich, Port Albert, and Clinton taking pictures of classes and other base activities. Many airmen came to his studio in Goderich to have their portraits taken to send home to family and friends. The Henderson Collection also includes wedding portraits, candid shots, and correspondence related to WWII air training in Huron County.

Haddy wedding – A992.0003.202a

Fannie Lavis and Cpl. Wesley F. Haddy, from Seaforth, were married on Aug. 6, 1945. Miss Lavis had two parties hosted for her by her friends before her wedding, including a crystal shower, according to the Huron Expositor, as found in our online collection of Huron Historic Newspapers.

Holmes Wedding – A992.0003.179a

Sgt. Cecil R. Holmes married Lorraine Eleanor Atkinson on June 10, 1944. Their wedding was held in the Dundas Central United Church in London, and the Clinton News Record reported on the event. During the 1940s, newspapers would describe the clothing, decorations, and events at the ceremony for their readers.

“The Church was attractive with Peonies, Ferns, and Palms, and was lighted with tapers held in candelabras. C.E. Wheeler was at the organ and the soloist was Miss Edna Parsons, who sang ‘Because’. The bride was given in marriage by her Uncle. A.G. Atkinson of Detroit. She was dressed in a filmy white net with panels of brocaded net adored with bows of white velvet and orange blossoms in the full skirt, which ended in a slight train. The dress was fashioned with sweetheart neckline and long sleeves. An illusion veil fell in three lengths from a flowered Headdress and she carried American beauty roses, “ (As published in the Clinton News Record, 1944-06-15, pg. 8, from our online collection of Huron Historic Newspapers)

Note that the dress in the description doesn’t match the image. It’s likely that Mrs. Holmes wore a different gown for her wedding than she did her wedding pictures. Wedding dresses during the Second World War were often shared or passed between women to aid in the war efforts and to avoid using excess fabric when rations were in place. Other women would simply wear a fine dress from their closet instead of a dress specifically meant for the ceremony.

Wagner Wedding – A992.0003.178a

Helen Marguerite Miller and Roy Wagner were married on June 5th of 1945, at Wesley Willis United Church in Clinton, ON. They went to the home of the bride’s family for a buffet lunch and reception.

“The bride, given in marriage by her father, wore a floor length gown of white brocaded satin, fashioned on princess lines with a sweetheart neckline. Her embroidered floor length veil was caught with orange blossoms and lily of the valley, and she carried a bouquet of white carnations, bouvardia, and lily of the valley.” (As published in the Clinton News Record, 1943-06-10, from our online collection of Huron Historic Newspapers)

As the Huron County Museum continues to digitize more images from the Henderson Collection, perhaps we will find more weddings celebrated by the men and women of the RCAF army bases in Huron County. There were many weddings held without a notice in the paper, making it a bit harder to find public information about the ceremony. I hope that the descriptions that do exist, and the smiling faces of the wedding parties, will let you imagine these beautiful times of joy during such a difficult era.

by Amy Zoethout | Jul 27, 2021 | Blog

If you’re out touring County Roads this summer, you may notice some new brown and white heritage signs marking Huron County’s historic settlements. The project was initiated by the County’s Public Works Department as a way to remember these communities that once existed in Huron. To date, 23 signs have been erected, including three signs marking communities that still exist, but under a different name. These signs have the word ‘historic’ added to show their historic name, like Ainleyville, which is still a thriving community now known today as Brussels. This summer, our student Maddy Gilbert will explore the history of some of these settlements.

Postcard of Main Street Brussels, postmarked 1909. Source: Archival Collection of the Huron County Museum

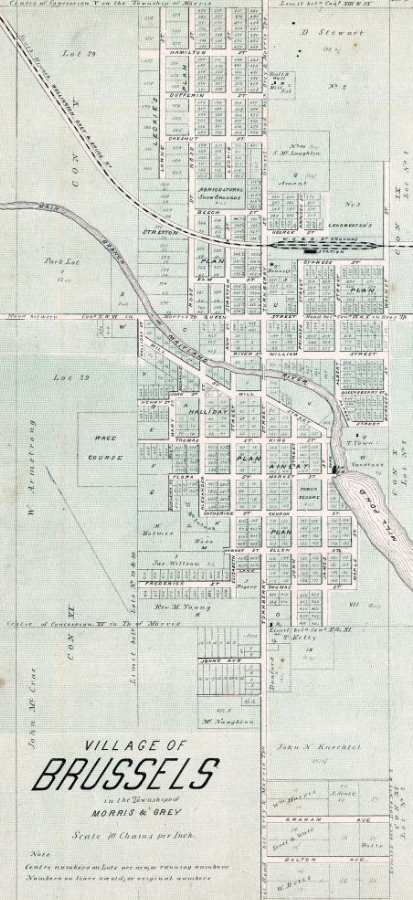

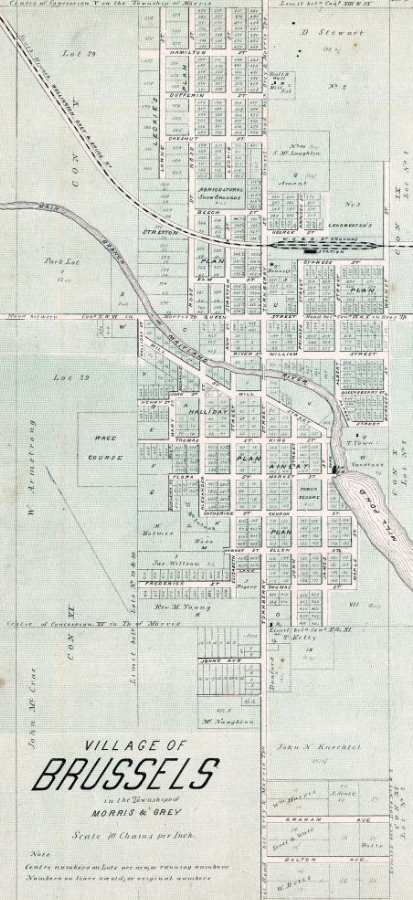

This 1879 map shows the village as “Brussels.”

Brussels found its beginnings in 1854, when William Ainley bought 200 acres of land on the Maitland River. In 1855, he laid out a town plot and named it Ainleyville, after himself. On April 1, 1856, he sold all of his land to J.N. Knechtel. Between 1860 and 1875, three fires completely destroyed the main street. Ainley donated land that was to be used for a market square, but it was converted into a park.

The Wellington, Grey and Bruce Railroad opened a line off of their Palmerston to Kincardine line, officially linking Ainleyville to a railroad. When the railway opened in 1874, there were three different names credited to the same place. Ainleyville was the name given to the village itself, Brussels was the name of the train station, and Dingle was the name of the post office.

One reason credited for settling on the name Brussels, was that railway workers were given the option to name the new train station. As many of the railway workers were of European descent, they chose Brussels after the capital of Belgium. Brussels was accepted as the official name for the village on Dec. 24, 1872, when it became Huron County’s first incorporated village.

Brussels sits at the intersections of Huron County Road 12 (Brussels Line) and Huron County Road 16 (Newry Road.) Brussels is 25 km southeast of Wingham, 25 km northwest of Seaforth, and 16km south of Wroxeter. Brussels was amalgamated into the Municipality of Huron East in 2001.

Learn more:

by Amy Zoethout | Jul 21, 2021 | Blog, Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History, Uncategorized

Kyra Lewis, Huron Historic Gaol outreach and engagement assistant, explores the architectural history of the Huron Historic Gaol.

The Huron Historic Gaol is a one of a kind building: predating Confederation, this anomaly has stood for over 181 years. Despite being made of predominantly stone and lumber, it has survived fires, being struck by lightning twice, and a tornado. However, its survival is not the only thing which stuns visitors about this incredible building. The Gaol’s architecture is one of the only of its kind in Canada standing today. This blog post will explore the architectural history of the Historic Gaol, and how and why its structural significance is honoured 181 years later.

Settlement began in Goderich as a result of the development of the Huron Tract in the 1830s; at the time, Goderich and the surrounding area were part of the London District. However, residents in the area felt disconnected from the district government and their affairs. Back then, in order to qualify as a County, you must possess a local government, and to do that, you had to have both a Courthouse and a Gaol. So in 1839, a contractor named William Geary began clearing land allocated by the Canada Company to build a Courthouse and Gaol, with the grand objective of establishing a local government for the County of Huron. The location was decided based on the fact that, at the time, the Gaol was situated outside the town. The location of the Gaol was considered ideal as it was distant enough to host undesirable residents, but still close enough to town for the convenience of court officials.

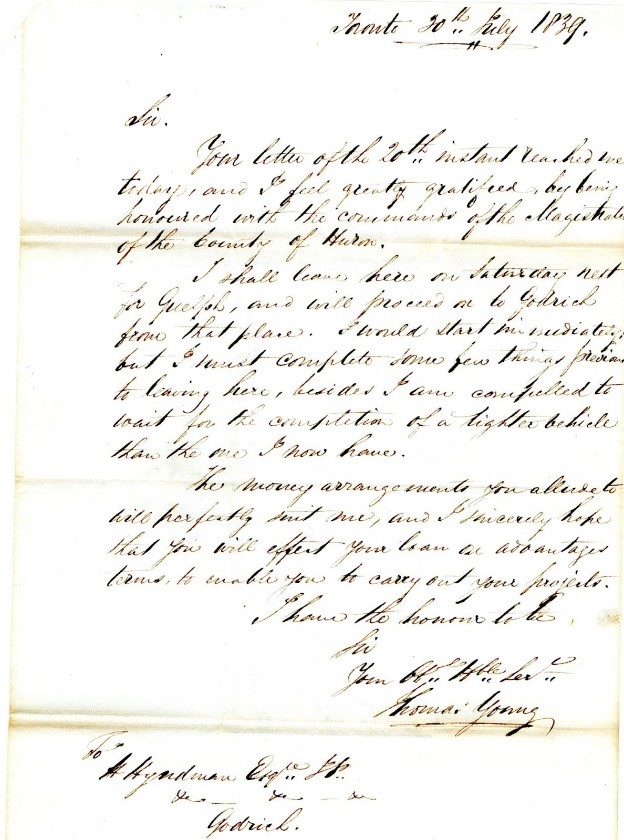

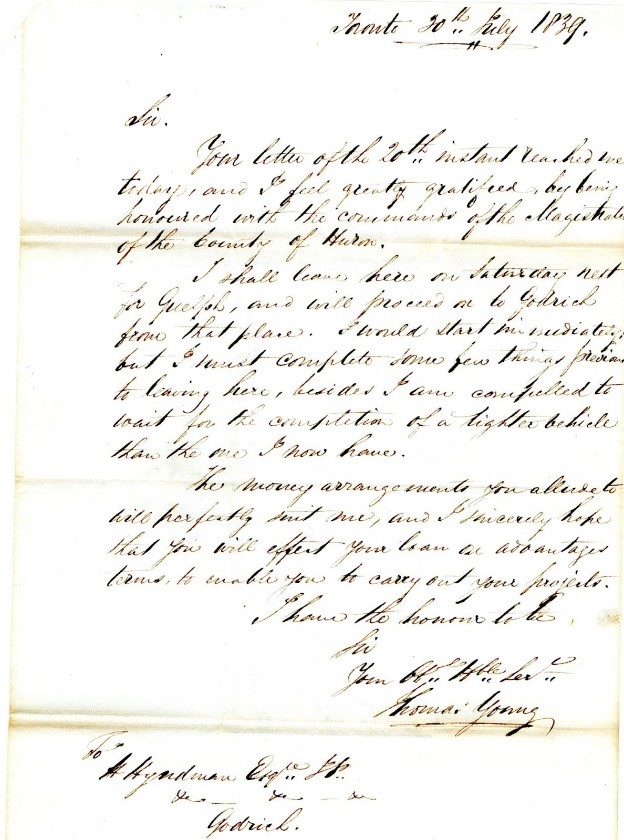

Letter from Thomas Young expressing his opinion and pleasure to take on the Gaol contract for Huron County.

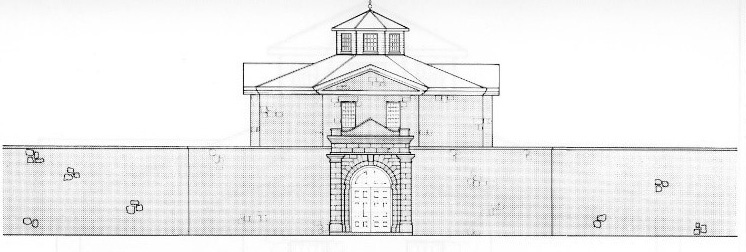

The project was given to Toronto architect Thomas Young. Young was born in England and had emigrated to Canada by 1834; until 1839 he was a drawing master at Upper Canada College. He received many commissions, one of which was to design King’s College in Toronto, which was completed in 1845. Young also received several other commissions between 1839-1844 to design, including the Wellington District Gaol and Courthouse, the Simcoe District Gaol, the Guelph Courthouse, and the Huron District Gaol. Many of Young’s designs were inspired by historic architecture, paying homage to neoclassical styles he utilized as an artist. This style consists of grandeur and symmetrical designs, similar to that of Roman and Greek buildings such as the Pantheon, located in Rome. Neoclassicalism became extremely popular in Italy and France in the mid 18th century, and was a very prominent influence in Young’s architectural designs and drawings.

Building materials for the Huron Gaol were sourced locally or imported via schooner from Michigan. A public posting requested “400 Cords of Stone – District of Huron Contract”, it was stated that the stone could be no less than “12 inches thick for the building of walls 2 feet thick”. This local stone came from the Maitland River, which flows through Huron County just to the north of the building. While local stone was used to construct the walls of the Huron Gaol, “coping and flagging” stone, which was predominantly used around the windows of the Gaol, was brought in from Michigan. Many other tenders were let for the project, such as 4,500 board feet of hewn timber, as well as blacksmith work and plastering.

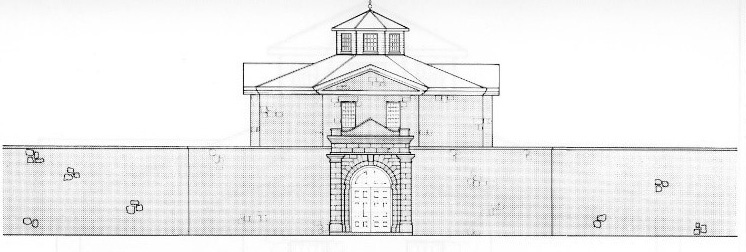

Drawing of the Huron Historic Gaol from Nick Hill’s report Huron Historic Gaol Goderich: A plan for restoration

PRISON REFORMATION

Young’s design for the Huron Gaol was inspired by Jeremy Bentham, an English philosopher. Bentham was devoted to reformation and rehabilitation and was curious about how prison design could contribute to the reform of criminals. Bentham popularized the panopticon, meaning “all seeing,” which precisely reflects the intention of the architecture. Panopticon designs allowed Gaol staff to observe prisoners from a centralized point, without the prisoners knowing when and if they are being observed. This structure was created to enforce compliance on prisoners, as they always had to act as though they were being watched. Due to the threat of constant surveillance, the theory of this design suggested that prisoners would then behave and conform to ideal behaviour. The invasiveness of always being able to be seen was stressful for prisoners, and thus they were more likely to comply with reformed behaviour. This was the intent of prison reformists such as Bentham, as their main objective was to create functional prisons that ran on limited manpower, but generated successful results concerning rehabilitation. Bentham believed that learning skills and completing tasks accurately and effectively while in a panopticon prison would ultimately contribute to their rehabilitation and readmittance into society as a better person.

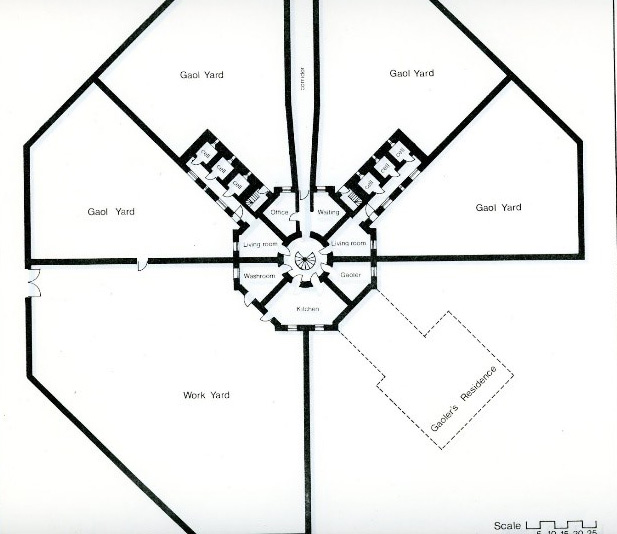

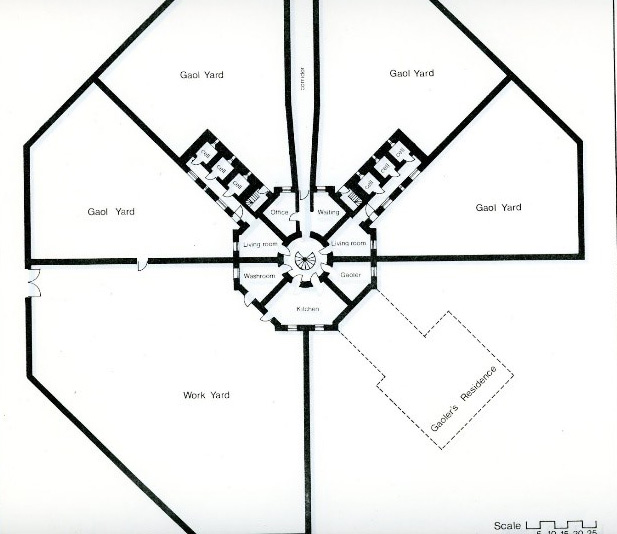

Drawing from report Huron Historic Gaol Goderich: A plan for restoration, by Nicholas Hill.

The panopticon was very prominent in the Gaol’s original design, as the Gaol itself has a centre building, with walls jutting out like spokes on a wheel. This was obviously intentional, as the third floor cupola allowed for staff to see each courtyard from one centralized point. Prisoners in the yards were therefore always observable, so there was an immense amount of pressure to behave. However, the cupola was not utilized nearly to the extent it would in a classical panopticon structure. The building’s courtyards were the only instance where panopticon design was implemented, as the rest of the building used a separate system. For this reason, the architecture still allowed for prisoners to have some sense of privacy and independence when in their cells. Thus Bentham’s ideology was not entirely encapsulated within Thomas Young’s design of the Huron Gaol, as only one aspect of the Gaol operated with this level of surveillance. Architect Nick Hill regarded this in his 1973 report to Huron County Council, mentioning that the design had “remarkable geometric clarity and functional arrangement based on the octagon”.

Another systematic influence that was used in the Huron Gaol’s design, was the separate system. This concept, oddly enough, was actually a contrast to the panopticon design. It enforces that prisoners stay isolated from one another, and can only be seen by guards when they enter the individual prison blocks. While the panopticon design was utilized in the structural elements of the courtyard, the separate system was incorporated within the Gaol’s cells. The act of keeping prisoners separate was significant as the Gaol was particularly small. This method ensured there would be fewer issues concerning fights and other conflicts amongst the prisoners. Solitude was also a major influence in many forms of prison reform around the 19th century. This form of confinement was designed to make prisoners easily controlled. Maintaining a sense of loneliness and isolation allowed for prisoners to feel more vulnerable and thus more compliant to the whims of the system they were incarcerated in. Eliminating that sense of unity and togetherness with other prisoners, in theory, would alleviate the possibility of revolts and violence as well.

The Huron Gaol implemented this in its cell design. There are four different cell blocks, with corresponding day rooms. Blocks one and two are on the first floor, with blocks three and four located on the second floor. The third floor, where the courtroom stands, has four individual holding cells. Every cell is oriented facing one direction, so other prisoners within the same block cannot see each other when in their individual cells. Historically, women and men were separated into different blocks, as mentioned in the Rules and Regulations of the Huron District Gaol detailed in 1846. This document stated that male and female prisoners were to be “confined in separate cells, or parts of the prison…as far as the dimensions, plan, and accommodations may allow”. At this point in time, prisoners were also separated into “classes” which were generally not permitted to intermix. For example: “1st. Prisoners convicted of felony. 2nd. Persons convicted of misdemeanors and vagrants. 3rd. Persons committed on charge or suspicion of felony. 4th. Persons committed on charge or suspicion of misdemeanors, or for what sureties; and in cases where necessity may require it, and circumstances admit, the sheriff may confine female prisoners in the rooms set apart for debtors. 5th. Debtors and persons confined for contempt of court on civil process.” The distance between each cell block also provided a sense of seclusion to ensure the safety of inmates.

The Gaol was a significant building for many reasons, however one of the most significant was the newly implemented techniques centred around prison reform. Prior to Jeremy Bentham and other incredible architects, sociologists, and philosophers, prisons were not based around reform. Prisons prior to the influence of such forward thinkers, were incredibly inhumane, as the concepts of rehabilitation and amelioration were relatively modern concepts in the early 1800s. There were a few gaols that implemented this philosophy, such as the Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, Auburn in New York State, as well as one in California. Thus, when Thomas Young utilized Bentham’s ideologies, it was one of the very first prisons existing at the time to be influenced by the new age philosophies of rehabilitation. Despite the Huron Gaol being of a much smaller scale, its design was truly revolutionary and ground breaking for its time.

Architect Nick Hill observed these concepts when he reflected on the Gaol’s structural uniqueness in the 20th century. Hill evaluated the significance of Bentham’s efforts of reform; “They engendered an attitude towards prisoners which saw the conclusion of exile, flogging, branding, maiming, the stocks and pillory, drawing and quartering.” The social changes these prisons inflicted on society were no small feat, as it signaled changing preconceived norms surrounding prisoners and criminal punishment.

Despite the Gaol’s incredible advancements in prison reform, there were several instances during its long history when councillors approved improvements be made to the Gaol to ensure functionality and proper treatment of prisoners. As there were no facilities for the elderly or the homeless until 1895 when the House of Refuge was constructed in Huron County, the Huron Gaol became a place of refuge for many. At its highest capacity, the Gaol held over 20 people, despite only having 12 cells and four holding cells. Its expansion became a necessity in order to ensure the Gaol was capable of executing the needs of all its inhabitants. For example, in July of 1853, the walls of the Gaol were deemed “insufficient for security” by the Grand Jurors. Despite this topic being brought to the Council’s attention in 1853, the Gaol walls were not expanded until July of 1861.

Aerial view of the Huron Historic Gaol showing walls as they stand today.

The renovation to the walls was undertaken after the Canada Company formally transferred the Gaol land to the County of Huron. Recommendations arising in 1856, following concerns around escapes from the Gaol, led to the walls being extended by two feet in height with loose stones being installed at the top of each wall. These stones were meant to come loose if a prisoner attempted to escape, causing them to fall to the ground when they grabbed a loose stone. William Hyslop was hired as contractor to renovate the walls, and was paid 27 pounds, 12 shillings, and 6 pence for “repairs to the Gaol wall”, as documented in council minutes from 1855. In the 1862 council minutes, William Hyslop is recompensed again for his efforts on the Gaol walls, after the County purchased the surrounding land to extend the walls outward, expanding the yard. The walls, as they stand today, are 18ft high and 2ft underground to ensure no prisoner could go over them or tunnel beneath. Other major improvements of the Gaol included the installation of a slate roof, as well as a bathtub in 1869. The original wooden bathtub was upgraded to copper in 1895 and a flush toilet was also installed. These changes were made for the health and well-being of the inmates, as health and hygiene were only recently being regarded as a necessity. Especially to avoid sickness and disease spreading through the relatively small facility.

The Huron Gaol has had an incredible 181 years of history in the County, and its captivating architecture represents incredible structural and architectural innovation for its time. The Huron Gaol is not only an incredible piece of history, but an amazing representation of the evolution of prison reform, rehabilitation and human rights.

Online Sources:

Primary Sources:

- H. Belden & Co. “Illustrated Historical Atlas of The County of Huron ONT: Compiled Drawn and Published from Personal Examinations and Surveys”. Toronto: 1879.

- Lizars, Daniel. “Rules and Regulations for the Huron Gaol 1846”. Rowsells and Thompson Printers. Toronto: July 24th 1846.

- Hill, Nicholas. Huron Historic Gaol Goderich: A plan for restoration prepared by Nicholas Hill. Undated.

Even small editorial changes which found room for community announcements, movie showtimes, advice columns and crossword puzzles were intended to position local news so that papers provided little bouts of day-to-day wisdom, small-town gossip and casual distraction. In an October edition of the Exeter Times-Advocate published in 1969, readers were treated to a horrorscope, an inverted horoscope which only offered bad advice. Pisces were told that “Long trips are not advised today. Neither are short trips. It might be well to stay in the house. Try not to think,” whereas Capricorns were reminded it was “A good day to pay off your bills, if you only had the money. Be thankful you have a roof over your head,” (Exeter Times-Advocate, Oct. 23, 1969, pg. 9)