by Amy Zoethout | May 26, 2021 | Media Releases/Announcements

Residents interested in helping to preserve and shape how local history is presented for the future can now make their voice heard. By joining the Museum’s Collection Committee, interested individuals will have a say in how the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol grows, expands and diversifies the stories shared through the Museum’s unique collection.

The County of Huron invites applications for open position(s) on the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol’s Collections Committee. The positions are for volunteer community members from Huron County. The committee welcomes applicants that represent different communities, backgrounds, age groups, and cultures across Huron County, including newcomers and generational residents. Volunteer terms are for one, two, or three years with the potential of two consecutive terms.

The Huron County Museum’s collection is built from community donations from people, homes and businesses across Huron, following a collections policy and mandate.

“This is a great opportunity for those who are passionate about Huron County’s ongoing history and heritage.” said Acting Director of Cultural Services Elizabeth French-Gibson “If you love material culture, and want to engage others with the memories, stories and community ties that can be evoked so powerfully by objects from the past then this is a great opportunity for you!”

The Collections Committee presents a volunteer opportunity that is short on time-commitment, but makes a long-term impact on how our community recognizes, prioritizes and preserves history close to home.

The purpose of the Collections Committee is to advise County Council with respect to matters pertaining to the Huron County Museum and Historic Gaol collection. Recommendations include review of short and long-term planning regarding collections, site policies in relation to collection development, and requirements of the Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture Industries’ Museum standards.

“When I was a child, a visit to the pioneer museum, which is what we called it then, was a confirmation that you don’t throw anything out; there was a story or use to every item,” said Collections Committee member Rhea Hamilton-Seeger, who shared what this volunteer experience has taught her. “As a member of the Collections Committee, I now get to learn more of the stories and appreciate what people collect and donate. One of the criteria for items to be in the Collection is that they relate to our [Huron County] history. While I would like to keep everything, there are some unique pieces that simply don’t relate. The staff of the Huron County Museum and this committee work hard to ensure a home is secured where these items do relate. A very interesting committee to be a part of and I have been able to share some of the stories with friends and better understand my local museum and how it teaches us, and reminds us, of our history.”

Be an active part of the Huron County Museum and Historic Gaol’s mission to engage our community in preserving, sharing, and fostering Huron County culture! The time commitment for volunteering is limited to attendance at committee meetings held every third month, generally on Tuesday mornings as scheduled by the Committee.

Those interested in applying for the volunteer position of Huron County Museum Collections Committee Member can submit a written application by Monday, June 28, 2021 to:

Acting Senior Curator

Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol

110 North St., Goderich, ON, N7A 2T8

museum [@] huroncounty.ca

To learn more about the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol’s collections:

by Amy Zoethout | May 20, 2021 | Blog, Collection highlights

Take a closer look at the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol and its collections as staff share stories about some well-known and some not-so-well-known features, artifacts, and more. In the last of a three-part series, Registrar Patti Lamb takes a closer look at deaccessioning artifacts from the Museum’s collection. Read Part 1 on Museum’s Secret Codes and Part 2 on Collecting at the Huron County Museum.

The Collection at the Huron County Museum is quite large and began with the collection of Joseph Herbert (Herbie) Neill. When Mr. Neill opened the Huron County Pioneer Museum, he brought his own collection and many people continued to donate more items regularly to the Museum. The Museum has actively been collecting artifacts since 1951. In the early days, the collections mandate was greater and objects came into the Collection from all over Ontario and in some cases other parts of Canada. Since that time, there has been an increase in the number of County and Municipal museums, as well as independent museums with specific collections focus.

Presently, many museums are focusing on refining their collections. Previous collecting without a mandate has resulted in museums having a lack of storage space, overcrowding, and items outside of their current mandates. Museums have been encouraged to have a Collections Policy and Collecting Mandate. In the case of the Huron County Museum, items coming into the Collection must have historical relevance to Huron County. Part of the Collections Policy must also be a policy on deaccessioning.

Deaccessioning is the process to officially remove an item from the listed holdings of a museum. It is never taken lightly and has very strict policies and procedures associated with it. Rules and regulations from the Ontario Ministry of Heritage, Sport, Tourism and Culture, as well as County and Museum policies must all be adhered to. The Huron County Museum has actively started to look at deaccessioning as a way to refine the Collection to be more clearly Huron County focused and to make the best use of current storage space.

These uniforms were recently deaccessioned from the Museum’s collection and transferred to the Bruce County Museum, as they were worn by Captain Shirley M. Robinson CD, from Kinloss Township, who was a Nursing Sister in the Canadian Forces.

The two main factors for deaccession are non-Huron County relevance or condition. If while searching the database, we find an artifact that was manufactured or used somewhere other than Huron County it could be considered for deaccession. However, place of manufacture is not the only factor. For example, a plow or coat that was manufactured somewhere else but was used to plow the fields for 40 years in Colborne Township, or worn by a women from Exeter on her wedding day, makes it relevant to Huron County. If an artifact is in poor condition, and as such could cause damage to other artifacts or effect the safety of staff and visitors, it would also be considered for deaccession. Mr. Neill’s original collection would not be included in the deaccession process.

Occasionally, the Museum will be offered an artifact that has a strong story or provenance but is similar to several others already in the Collection. In this case, the Registrar will do research into the Collection by searching the database and files to find out the relevance of the other similar objects. If there are similar objects with no history, relevance, or in poor condition they may be considered for deaccession making room for the new object.

Once an object has been identified for potential deaccession, the Registrar will prepare a report to be presented to the Huron County Museum Collections Committee. This report includes any known information about the artifact and reasons why it should be deaccessioned. If the Collections Committee also finds that the artifact should be deaccessioned, the report is forwarded to County Council for approval. If County Council approves, then the deaccessioning process can begin. The object will then go through the following options until the appropriate one is found:

- Transferred to the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol “hands on” educational collection.

- Offered as an exchange, gift or private sale to other public museums, or similar public institutions.

- In the event that the artifact is not disposed of to the Canadian museum community, it may be deaccessioned through public sale. All monies obtained through the sale of deaccessioned objects will be used only for collection acquisition and care.

- As a final option, the artifact will undergo intentional destruction before witnesses by designated museum personnel or disposed of in a fashion (such as to a scrap metal dealer) which ensures it cannot be reconstructed in any way.

Signed paperwork and photographic documentation for all the above options is required and added to the object record. In most cases, option number two is the one that is used. The Registrar contacts the appropriate museum in the area that is most relevant to the object to discuss the transfer of the object. Since 2013 to the end of 2020, 439 objects have been transferred to other museums or institutions, returning them to the geographical areas where they truly belong and thus allowing the local residents and tourists of the area to enjoy, learn, and discover them.

This Fire Hose Reel was deaccessioned and transferred to Lambton Heritage Museum. It was used at Imperial Oil Refinery at Sarnia in 1892.

by Amy Zoethout | May 19, 2021 | Blog, Collection highlights

Take a closer look at the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol and its collections as staff share stories about some well-known and some not-so-well-known features, artifacts, and more. In the second of a three-part series, Registrar Patti Lamb takes a closer look at the Museum’s collections and the process of accepting and cataloguing donations into the collection. Read Part 1 on Museum’s Secret Codes and Part 3 on Deaccessioning Artifacts.

Visitors and members of the general public are often curious as to what happens behind the scenes at the Huron County Museum. Questions commonly asked to the staff are: what happens to the “stuff” once it’s donated; what does the collections staff do; where does the museum put all the “stuff”; and what happens when the museum is done with it? These are all really good questions and this blog is an attempt to share the different roles of the Collections staff and what happens when someone has donated something to the Museum.

Museum Technician Heid Zoethout, Registrar Patti Lamb, and Archivist Michael Molnar are three of the primary roles within the Museum’s Collections staff.

A Collections Team

There are three primary roles within the Collections staff. They are the Archivist, Museum Technician, and Registrar. Each role works separately within their own individual job descriptions but they all work together as a team.

The Archivist is responsible for the archival collection which includes all paper based, 2 dimensional items such as photographs, documents, diaries, and minute books. The Archivist processes donor forms; documents and catalogues the donations of archival material; and conducts research for or assists with research for others.

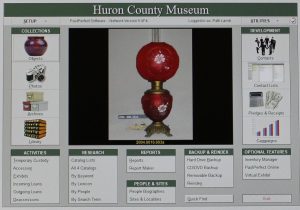

PastPerfect is the Museum’s Collections Management System

The Museum Technician is responsible for the housing and location of the artifacts. The Technician makes sure the artifacts are stored properly; are safely handled and displayed in ways that are not damaging; and locates the artifacts in the museum buildings and the collections database. This role also monitors temperature, humidity, and light levels.

The Registrar looks after the documentation of donations of three-dimensional objects; processes donor forms; catalogues the artifacts to include detailed descriptions and provenance; photographs the artifacts; and maintains PastPerfect, the Museum’s Collection Management Software. This role also looks after the documentation of incoming and outgoing loans as well as conducts research on objects in the Collection.

How to Donate to the Collection

When someone is interested in making a donation to the Huron County Museum, they need to contact the Archivist for archival material, or the Registrar for three-dimensional objects. This blog is going to focus on three-dimensional object donations, but the process is basically the same for archival material. Anything being considered for donation to the Museum must meet the collections mandate or criteria. Items must have historical relevance to Huron County, meaning they must have been used or manufactured in Huron County, or have a significant provenance (history) that ties them to the County. Artifacts should also be in good condition.

Once contacted to inquire about donating items, the Registrar will chat, either by phone or email, with the potential donor to determine the relevance of the items. Usually the donor will be asked to email some photographs of the object(s) so the condition can be determined and to make clear what the object is they wish to donate. Most times the donor will not be given an acceptance or denial answer right away. The Registrar wants to look at the potential donation, and take some time to do a search in the database to see if there are duplicate items such as the ones that are being offered. If the Museum does have several similar items, it needs to be determined if the ones in the Collection have a detailed story or history associated with them or if the new item would tell a better story.

Once it has been determined that the artifact will be accepted into the Collection, an appointment is made between the Registrar and the donor to bring the item to the Museum. At that appointment, gift forms (donor forms) are prepared by the Registrar for both the donor and Registrar to sign. Included on the form is the donor’s name, address, and contact information; item(s); and a detailed history (provenance) about the item. Information also includes where, when, and how it was used; by whom it was used; and how the donor came to have it.

By signing the donor form, the donor is stating that they have the legal right to the item and can therefore sign ownership over to the Museum. Once the form is signed, the artifact becomes the legal property of the Museum. If the donor wants an income tax receipt for their donation a further step will be taken. Prior to the appointment, the donor must obtain a written appraisal of the artifact. The appraisal must be on the letterhead of the appraiser or antiques dealer and accompany the donor to the appointment. The appraisal is given to the Registrar with the artifact and once the gift forms are signed, an income tax receipt will later be prepared and mailed to the donor.

Photographing an artifact is the last step in the cataloguing process.

Cataloguing the Donation

When the paperwork is complete, the cataloguing process can begin. Cataloguing an artifact includes assigning an object ID number and documenting as much information as possible about the object. A detailed description is required describing all the physical attributes of the item such as measurements, colour, material makeup, condition, and functionality. The record will also include how, where, and when the object was used. Often research is involved to discover important facts regarding the object, the family that used it, or the business from where it came. The history of an object is just as important as the object itself. For example, a quilt is just a quilt, but a quilt with a good description and detail about why it was made, who made it, who used it, and where it was used makes it much more interesting and relatable.

An object ID number is then added to the object in a way that does not damage the artifact. Textiles will have a cloth label sewn onto them and objects with harder surfaces have a number added that is removable should it need to be.

The last step in the cataloguing process is photography. Each object is photographed in detail showing all sides, close ups of significant or interesting parts, and any condition issues such as cracks or peeling paint. Photographs are then added to the record in the database and ultimately uploaded with the record to the Online Collection, which features over 6,000 artifacts from the Museum’s collection.

When the object is completely catalogued, it is placed in a temporary location in the main storage area for the Museum Technician to then find it a permanent home. The permanent location is documented in the database so the artifact is accessible to go on exhibit or loan, or be used in research when needed.

by Amy Zoethout | May 18, 2021 | Blog

Take a closer look at the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol and its collections as staff share stories about some well-known and some not-so-well-known features, artifacts, and more. In a three-part series, Registrar Patti Lamb takes a closer look at a museum’s secret codes. Read Part 2 on Collecting at the Huron County Museum and Part 3 on Deaccessioning Artifacts.

The Object Identification Number is an important part of the “secret language” used by museum professionals.

Most museum visitors are aware that the artifacts in the museum have numbers written on them. Most also know that the numbers somehow help to identify the objects. What most don’t realize, however, is what the numbers mean to the museum staff.

When museum staff look at an Object Identification Number (object ID), they can instantly tell what year the object came to the museum; if there were other objects that came in before it that particular year; whether it was part of a group of objects; and in some cases, whether or not there is a known donor. Using an object ID number to look up an object record in the museum database will show the staff everything that is known about the object. This includes physical description, donor, provenance (history), condition, use, and where in the museum the object is located.

Traditionally, museums use a three part numbering system. The first part lets staff know the year the artifact came into the museum collection; the second part indicates the group number of the artifacts that came in during a particular year; and the last number is the object number within that group. The first two parts of the number are what is known as an accession number (an object or group of objects from a single source at one time). When the third part of the number is added on, it becomes an object ID number specific to that object.

Accession and object ID numbers are an important part of the “secret language” used by museum professionals. They allow us to record and store, in one spot, important information about the artifacts as well as help track and locate them. The object ID is as important as the artifact, and without it, access to the information about the artifact would be difficult to retain and retrieve.

Object Identification Number shown on this Museum artifact.

by Amy Zoethout | May 4, 2021 | Artefacts, Collection highlights

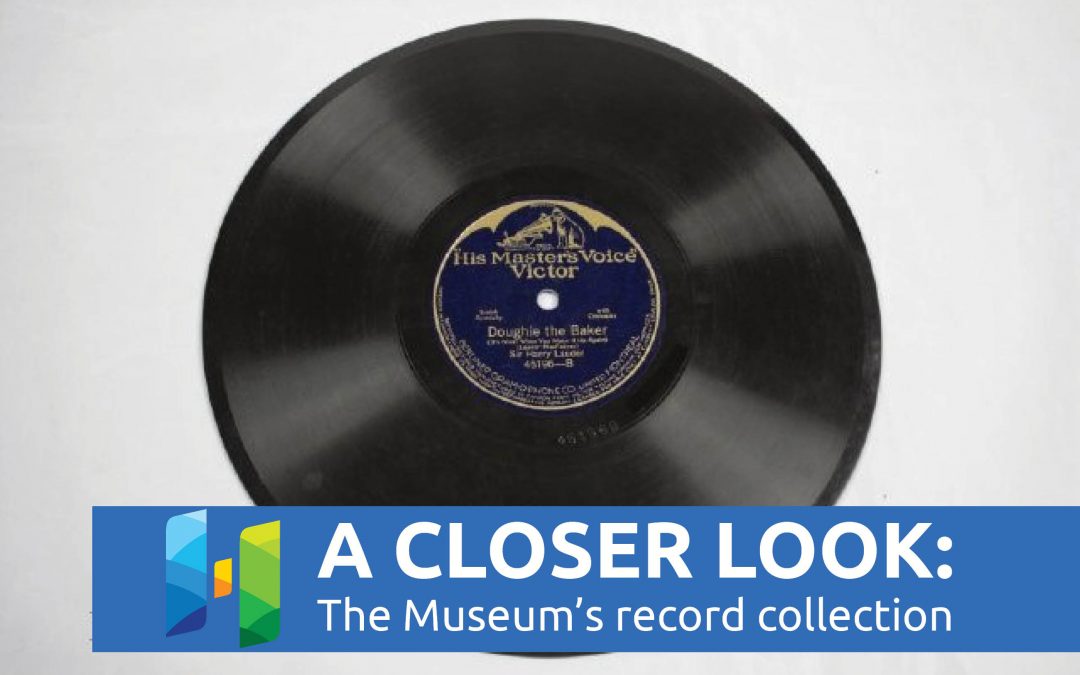

Take a closer look at the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol and its collections as staff share stories about some well-known and some not-so-well-known features, artifacts, and more. Acting Education and Programming Coordinator Dan Genis looks at the Museum’s record collection.

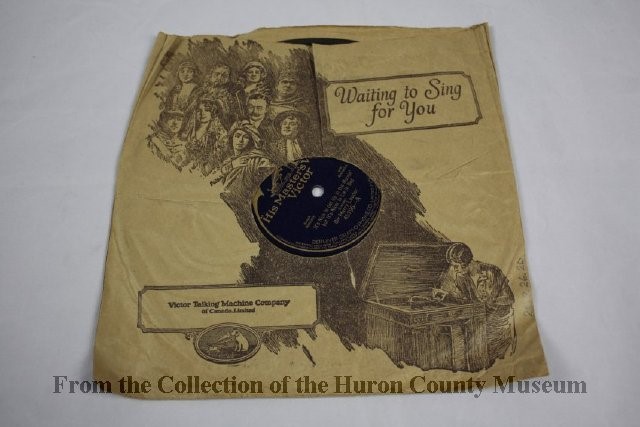

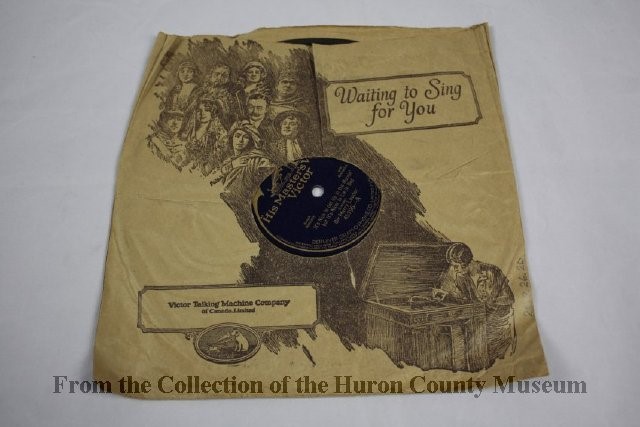

Record sleeve advertising the Victor Talking Machine Company of Canada Limited, featuring the slogan “Waiting to Sing to You.” Contains an early 1920s record by Harry Lauder. 2018.0026.002b

Did you know that Huron County Museum has a record collection?

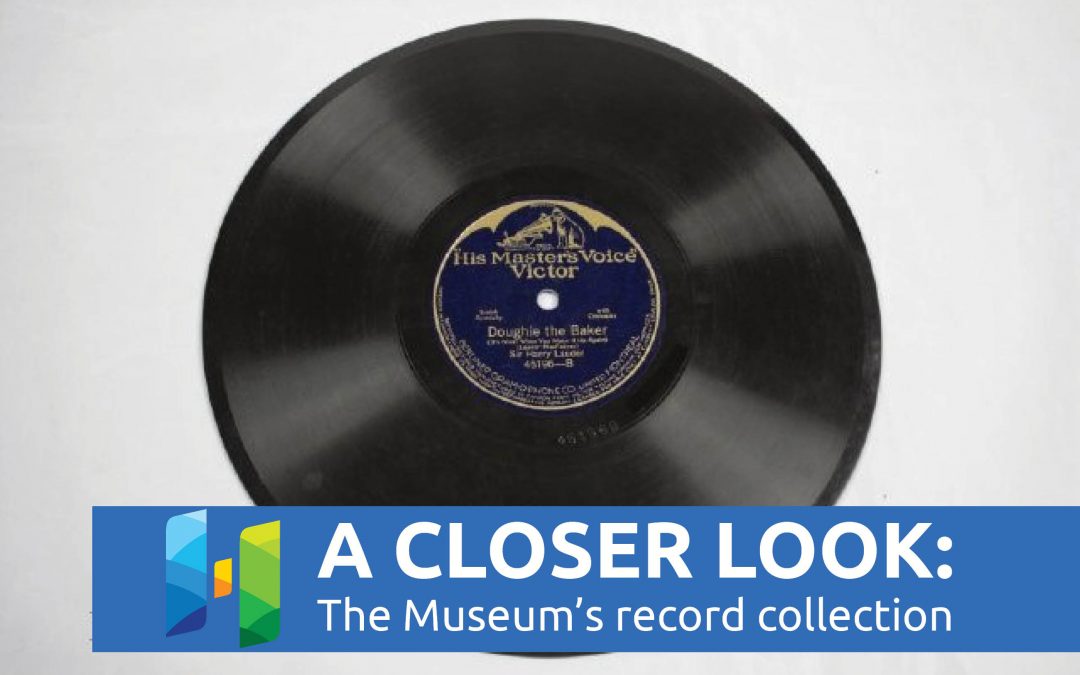

While you might assume that record collections only belong to hardcore music fans or collectors, the Huron County Museum has an impressive record collection of its own. The museum collection contains almost 200 records, largely dating from 1900-1970. Music is a vital part of a community’s culture, which makes music-related artifacts important as well.

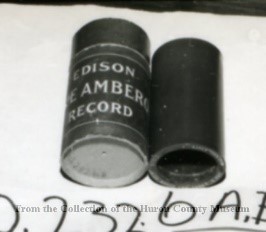

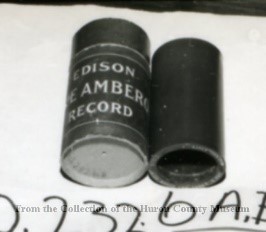

An Edison Blue Amberol phonograph record released in 1913. This 4 minute 17 second record plays “Alice Where Art Thou?” by Ernest Pike, originally composed by Joseph Ascher. M960.0232.006a

The collection begins with phonograph cylinders, commonly called “records”. Like the one in the above picture, the cylinders were meant to be played on a phonograph. Invented by Thomas Edison in 1877, early phonographs recorded sound as small grooves on a wax (later plastic) cylinder. To play the recording, the cylinder rotated and a stylus traced over the grooves and vibrated, reproducing the original sound. While in North America any sound-reproducing “talking” machine that uses records can be called a phonograph, in the United Kingdom (UK) the term more specifically refers to machines that play cylinders.

In 1889, Emile Berliner invented a phonograph that played discs records, calling it the “Gramophone.” Although disc records had been sold as early as 1889, it was not until the 1910s that they overtook phonograph cylinders as the record format of choice. Most disc records, including the “Harry Lauder” record in the picture above, were made with shellac. In the UK “Gramophone” became the term used to describe any disc-playing talking machine, but “phonograph” and “talking-machine” continued to be used in North America. This is especially confusing in Canada where all three terms had been and continue to be used interchangeably.

The “Concert Grand” talking machine (or gramophone), manufactured at the Gunn-Son-ola Talking Machine Co. in Wingham, Ontario. The gramophone was purchased by Lily and George McClenaghan and was always in their home at Whitechurch. 2018.0026.001a

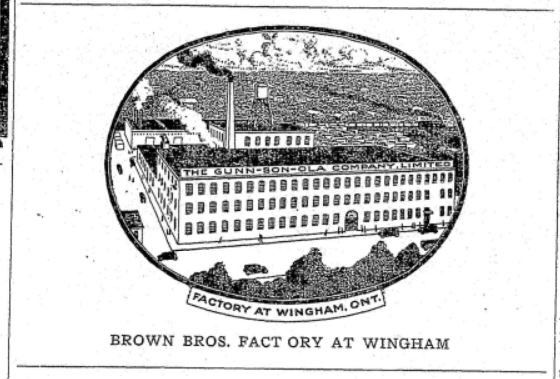

The Gunn-Son-ola Talking Machine Company was founded in Wingham by Michigan manufacturer William Gunn in 1920. Gunn had purchased the Walker and Clegg furniture factory located on Alfred Street. Gun-son-ola churned out talking machines and cabinets for over ten years, at its peak employing 162 people. The company went bankrupt in 1931 and was taken over by Brown Bros. Manufacturing, which reverted the factory back into the manufacturing of general furniture products.

In the 1940s Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) began replacing shellac in the manufacturing of records. These new “vinyl” records were more flexible and less likely to break, which also allowed for smaller grooves (“microgrooves”) which could store more music.

By the time “The Best of Vera Lynn” was released in 1968, vinyl records were the most popular way of listening to recorded music. In the early 1980s cassette tapes had replaced vinyl in popularity, only to be itself replaced by the compact disk (CD) in the 1990s.There has been a vinyl record revival in recent years, with vinyl sales in 2020 surpassing CD sales in the US for the first time since 1986.

To check out more of the Huron County Museum’s record collection, head over to our online collections database at: https://huroncountymuseum.pastperfectonline.com/

A drawing of the Gunn-son-ola factory in Wingham, which primarily made talking-machines and radio cabinets. By 1935 it was owned by the Brown Bros. Company. The Wingham Advance Times 1935-05-16