by Amy Zoethout | Mar 27, 2024 | Archives, Blog

Written by Collections Assistant Noah Chapman.

Recently, the Huron County Museum began the transfer of artifacts from the (now-closed) North Huron Museum. Among the items was this image of a group of World War One soldiers (object number 2023.0067.352). Unfortunately, the original label has worn off and the North Huron documentation did not have in-depth detail. The only information was the name of one of the photographed soldiers, his wife, and the donor’s name.

A mystery was at hand. One of the most important goals of the museum is to restore lost context to items in the collections. For us, this was an opportunity to conduct some practical historical research. In doing this, we were able to recall the memory of one of Huron County’s World War One servicemen.

The North Huron documents had these clues:

- The name of the donor that brought the picture to the North Huron Museum.

- The picture had belonged to Mrs. Emily Elston; she was an English War bride.

- Emily Elston had two husbands. The first was Bert Thomas, who she had met in a hospital during the war. He later died from the effects of a mustard gas attack.

- Emily’s second husband was named William Elston.

The person of most interest was Bert Thomas. We wanted to find out what unit he had served in and in what role. The problem is that “Bert” is a nickname that can be short for a lot of different names! Finding him would not be easy, as we did not even know what Huron community he had come from.

The first place we looked was online. Online obituaries and websites are a great place to find birth and death dates, spouses, and family members. Unfortunately, searches of the four available names did not yield much information; adding “Wingham” or “Huron County” to the search did not help with finding a lot about Bert or Emily. However, we were able to find records online for a William “Bill” Elston who served in World War Two. This was a good start, but it was unclear if this was the same William Elston that was married to Emily Elston.

The next clue we found was the obituaries of several members of the Elston families. Here, several clues came together to form a better picture of this family. From the obituary of Edwin Elston, we learned that most of the family was from Wingham. We also learned that Edwin and Bill were siblings. Edwin and Bill were sons of Emily (Thomas) Elston and William Elston. This helped to clarify that there were two William Elstons. The man I found the service record for was William Jr., “Bill”. Bill also had a half brother named Bernard Thomas, who was the son of one Albert Thomas. Albert Thomas is the “Bert” Thomas who served in World War One and was in the unidentified photo.

Even with a full name, it was still difficult to find information on Albert’s military service online. We tried another great free online resource, the Huron County Digitized Newspapers. Finally! We were able to find some evidence of his military service.

Albert had been a farmer in Bluevale and had four children with his first wife, who had passed away in February 1915. On June 24, 1915, the Wingham Advance-Times reported that Albert Thomas of Bluevale had auctioned off his farm stock and implements. At the age of 32, he left for London to enlist with the third Canadian Expeditionary contingent. This explained why Albert Thomas wasn’t listed as a member of the Huron CEF units (like the 161st Battalion). Such units were not formed until late 1915. While Huron County did have existing military units like the 33rd Regiment, recruitment had been slow. The Canadian Expeditionary Force had focused on urban recruits, rather than rural communities. This did not stop Huron County men, like Albert, from enlisting with urban regiments. On Feb. 2, 1916, the Wingham Advance-Times reported that Albert had enlisted with a Battalion in Woodstock. He returned home for a short visit before shipping out.

Now that we knew that Albert had been born in Bluevale, we were able to find Albert’s grave record. He enlisted with the 168th Oxford County Battalion. The 168th is the unit pictured in the North Huron Photograph. This is further proven by the remains of the label on the photograph. Part of a word- “ock” is still visible- “Woodstock”. We reached out to the Woodstock Museum. They also had a copy of this photograph, and that it was the 168th “Oxfords” Battalion.

The 168th (and Albert) embarked on Sept. 12, 1916 from Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. They disembarked on Sept. 22, 1916 at Liverpool, England. They deployed on Jan. 13, 1917 to France, where the unit reinforced other British regiments. Albert transferred to the Canadian Overseas Railway Construction Corps (C.O.R.C.C.) as a sapper. The role of the C.O.R.C.C. was to repair and expand railways in France. They supported the supply chain to the front lines, and dug trenches and fortifications. They would see action at Arras, Ypres, and Amiens; we believe that Albert took part in these actions.

Albert had a number of interesting experiences during the war. He caught trench fever early into his deployment and returned to England. While recovering from this illness, we believe he met his wife Emily Kate Austen, a nurse serving in a British hospital. Their son Bernard Thomas was born in 1917.

Albert briefly returned to France, but his fever relapsed shortly after. He was ordered back to England. While on passage back through the English Channel, the steamer in front of Albert’s vessel would be torpedoed by an enemy submarine. The passengers were transferred to Albert’s boat, which capsized due to being overloaded. Albert would be thrown overboard and would lose consciousness; he was unable to account for his rescue. Due to the cold water, he would contract malaria fever, which caused hip paralysis.

On Oct. 24, 1918, the Wingham Advance-Times reported that Albert was invalidated back to Canada, reuniting with his family. He began treatment for mustard poisoning in Burlington. His wife Emily and son Bernard would emigrate to Canada in 1919. The Wingham Advance-Times reported that Albert was still undergoing treatment in late 1919. On July 15, 1920, Albert “Bert” Thomas succumbed to diphtheria, a complication of his poisoning and previous illnesses. The 1921 census shows Emily and all five children still living in the area. Emily would move to Wingham, marry William Elston, and have three more children. Some of her children would also have military careers, serving in the Second World War and the Korean War.

We hope this look into the research that goes into our incoming collections was interesting! Through our ongoing research, we aim to recover, retell, and showcase these kinds of stories. As our research into the collection continues, keep an eye out for more expanded histories on our social media, at the Museum, and around the community.

by Amy Zoethout | Feb 29, 2024 | Archives, Blog, Digitization

Written by Jacob Smith, Digitization Coordinator for the Huron County Museum.

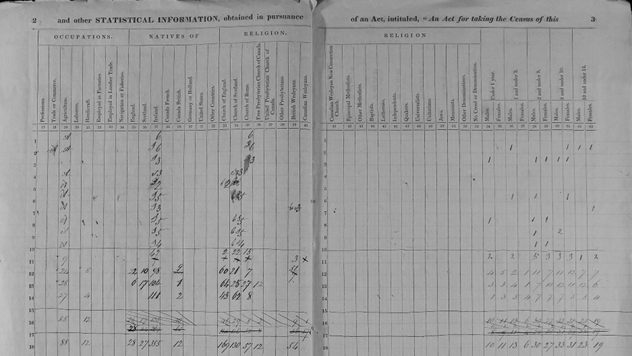

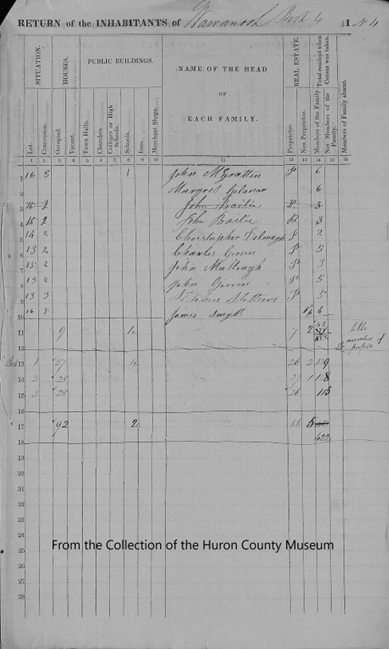

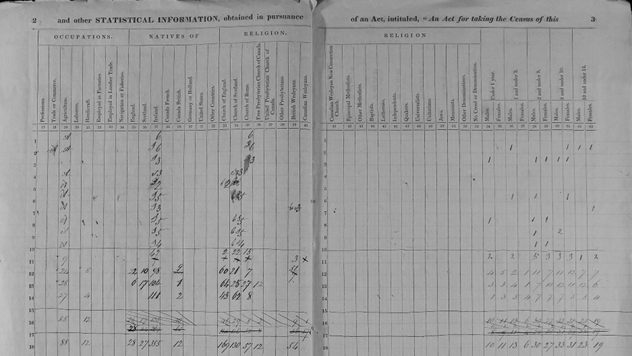

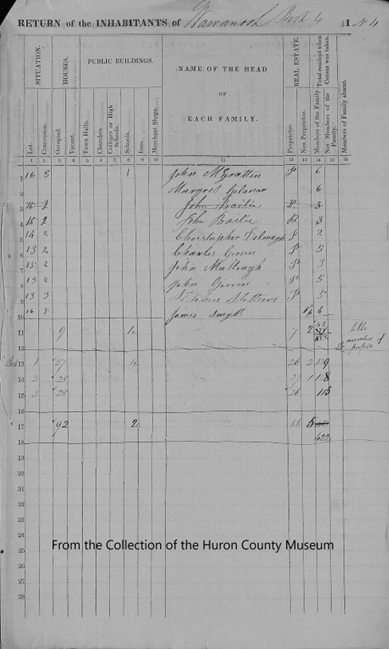

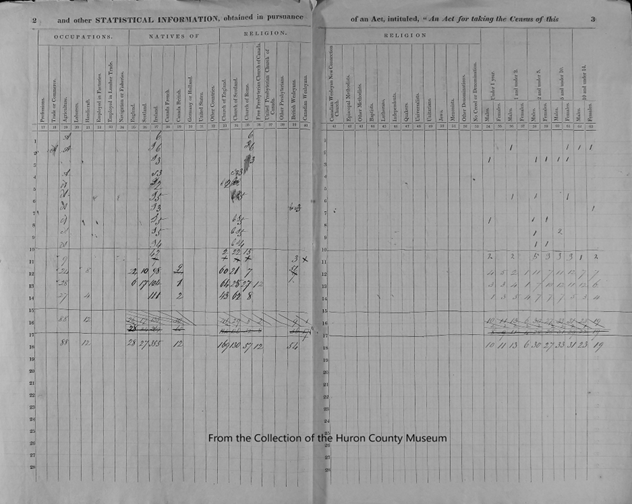

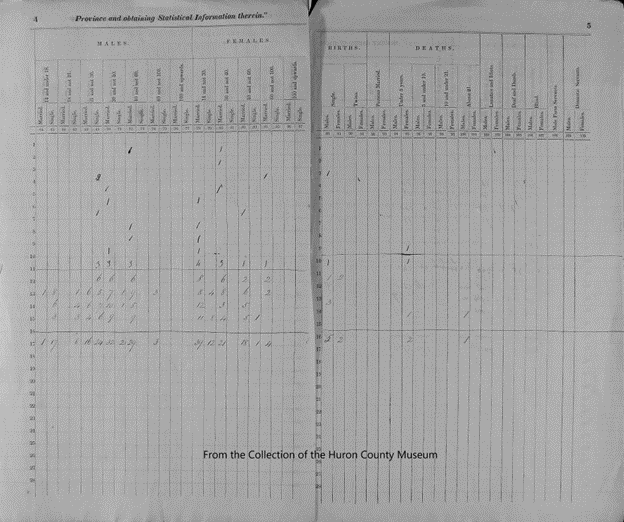

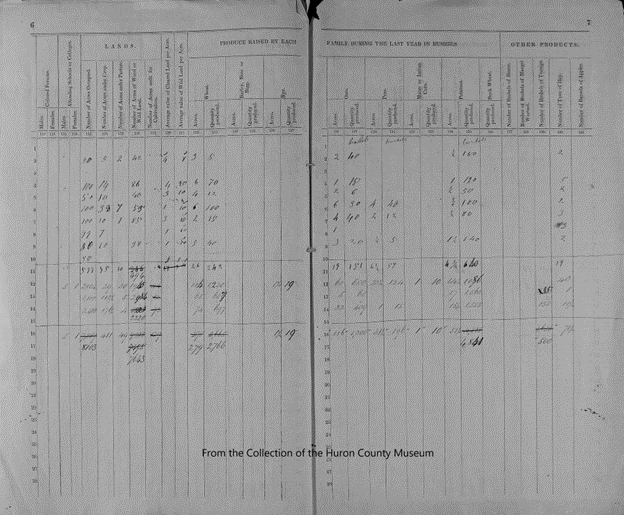

As part of the Huron County Museum’s ongoing digitization project, I have been busy scanning and uploading census records called Return of Inhabitants to the Museum’s online collection (which you can click here to view). The Return of Inhabitants are informative documents for genealogists. Information ranging from ages of family members to the types of livestock on each property are just two pieces of information that these documents provide. As someone who has a keen interest in genealogy, I was thrilled to find information about my ancestors. For example, I was able to find information on the Smith family in the 1850 Return of Inhabitants for Wawanosh Township, which can be seen in the image below.

The Return of Inhabitants are in book-like format. To read the information, you must follow the line numbers on the far-left side of the page. In the case of my ancestors, the Smith family, I must follow line number 10. Upon reading across the page, it is stated that James Smith and his family lived at Lot 16, Concession 5 of Wawanosh Township, they were non-proprietors of the land, and they were a family of four.

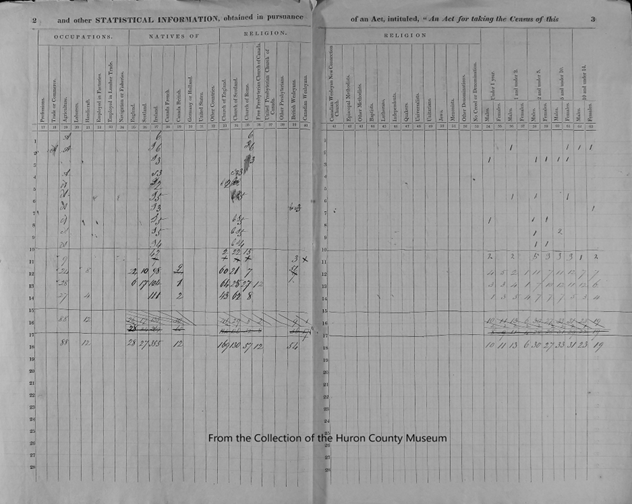

Looking at the next page, again looking for number 10 and reading across, we see that the Smith family lived on agricultural land, were natives of Ireland, belonged to the Church of Scotland, and had two children, a boy, and a girl, between the ages of 2 and 5.

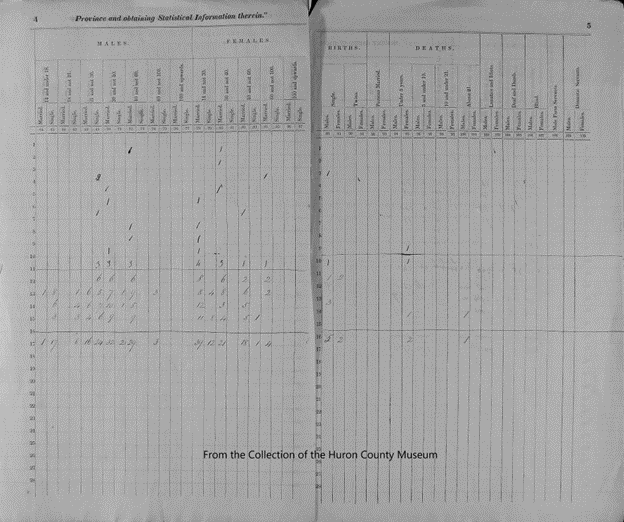

The next page shows that James Smith was married, and was between the ages of 30 and 40, and his wife was between the ages of 14 and 30. Also noted on this page was the death of a young girl. Upon further research of the Smith family, I learned a daughter of James and Margaret Smith had died of an illness while immigrating from Ireland to Canada.

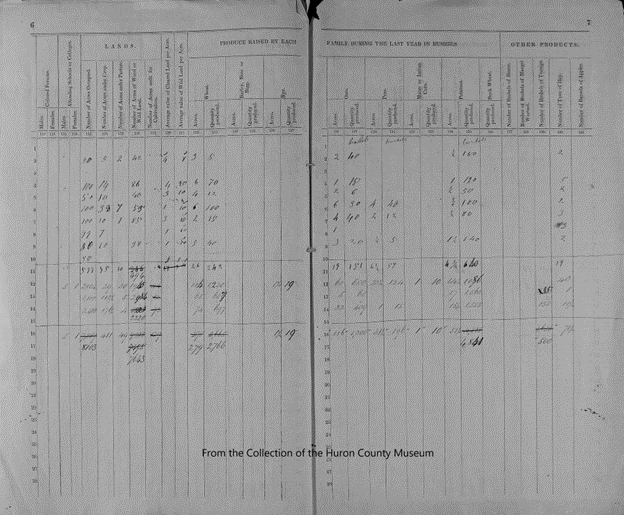

The next few pages document information about their property. James Smith and his family lived on a 50-acre plot of land. However, as seen in the image below, all agricultural information regarding their farm is left blank. I know from genealogy research that the Smiths immigrated to Canada in 1850, the same year this Return of Inhabitants was taken. It is possible that their farm was not agriculturally productive at the time this census was recorded.

Through the Return of Inhabitants, I was able to learn about my family history. Scanning and uploading these documents was a rewarding experience. My goal throughout the project was to digitize as many documents as possible, giving the opportunity for researchers to work from the comfort of their homes. I hope you find the Return of Inhabitants to be a useful source of information. Happy researching!

Looking for census records from the 1860s and 1870s? Click here to view digitized Assessment Rolls.

The Huron County Archives has additional census records that have not been digitized. Please contact the Archives for more information.

This project is funded (in part) in part by the Government of Canada

Ce projet est financé (en partie) par le gouvernement du Canada.

by Amy Zoethout | Apr 27, 2023 | Archives, Blog, Collection highlights

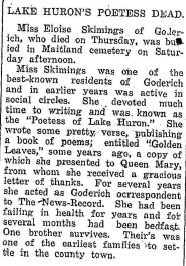

Eloise Ann Skimings was a poet, musician, music teacher, composer, newspaper columnist and author. She was described as “one of Goderich’s best-known citizens” and also “The Poetess of Lake Huron”. She was often seen in Goderich wearing elaborate dresses, hats, gloves and a parasol, and was described, by many, as “our distinguished townswoman”.

Eloise was born in Goderich on Dec. 29, 1837, to Mary Rielly Mason Skimings and James Skimings. She had two brothers, William and Richard, and one sister, Emma Jane, who died at two years, seven months.

Eloise was one of photographer Reuben Sallows’s favourite models. Her photos were reproduced as postcards and some can be found in the Huron County Museum’s collection as well as the prints. A large oil painting of her hangs in the Museum’s Victorian Apartment display above the fireplace.

As an author, she dedicated many poems to the people she encountered during her lifetime and the subject of many of her poems reflect the land, life and times she lived in. She published a book of poetry Golden Leaves in 1890, which was lengthened to nearly 1,000 poems when it was reprinted under the same title in 1904. Her brother, lawyer and lieutenant Richard Skimings, was also an author of poetry and prose. Twenty pages of Golden Leaves were set aside for publication of his verse versus 326 pages for hers.

Golden Leaves was exhibited in the Library of the Women’s Building at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition (World’s Fair) in 1893. This book was one of only two, penned by Canadian women, to be exhibited within that library building.

Also a music teacher, she composed and published music such as I think of Thee, Alice, National March, Forget Me not Waltz, and Golden Blossoms.

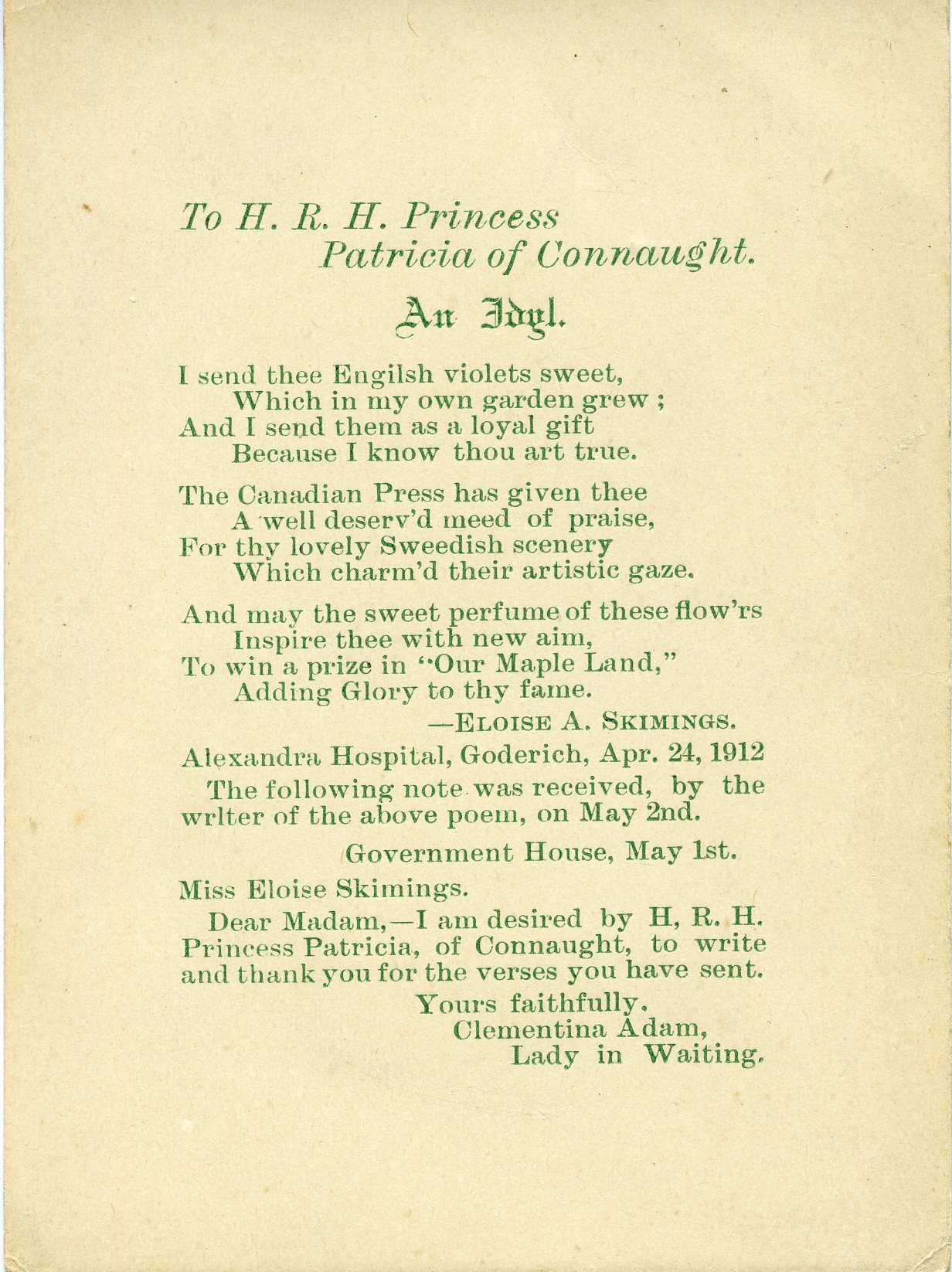

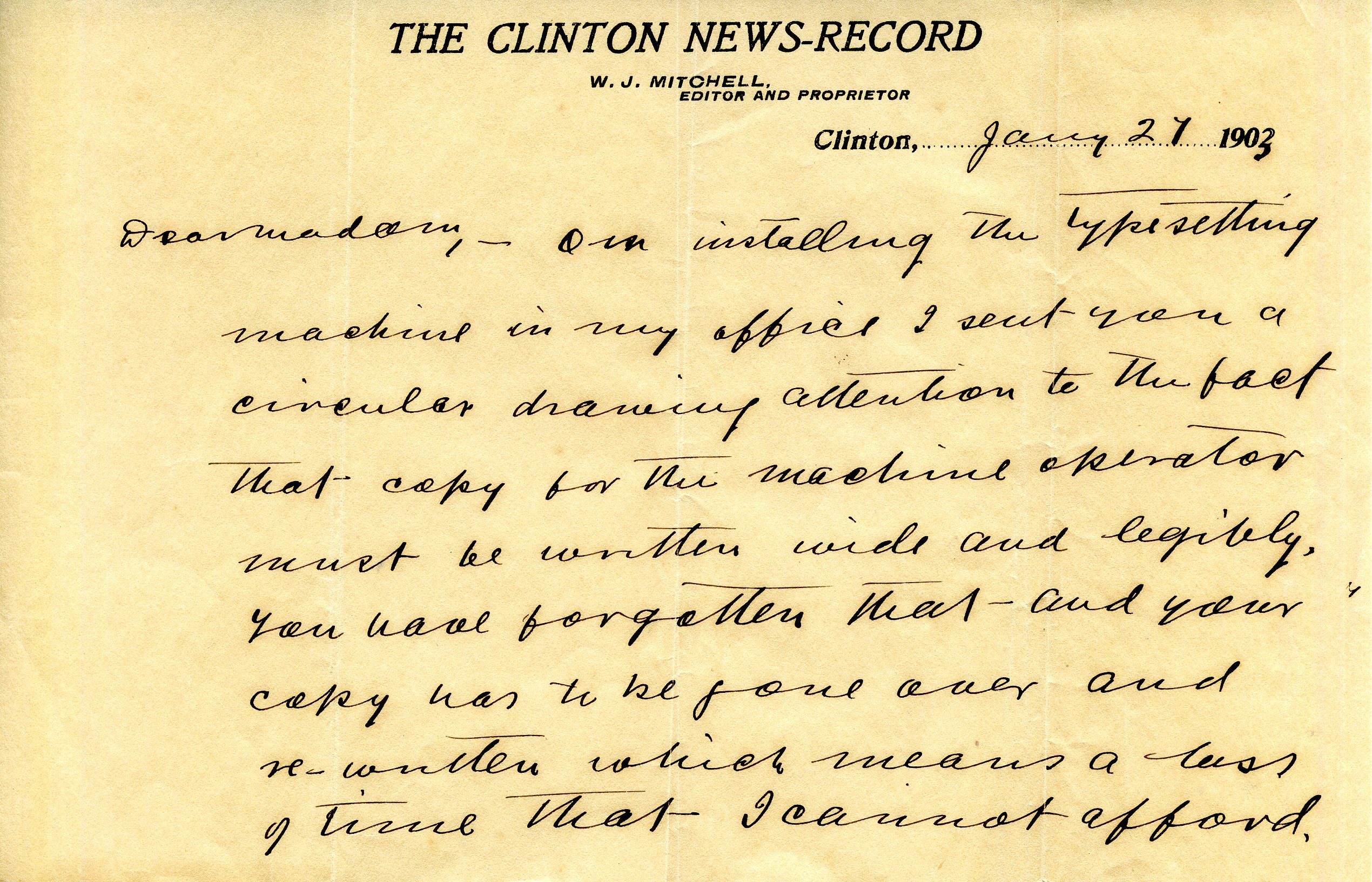

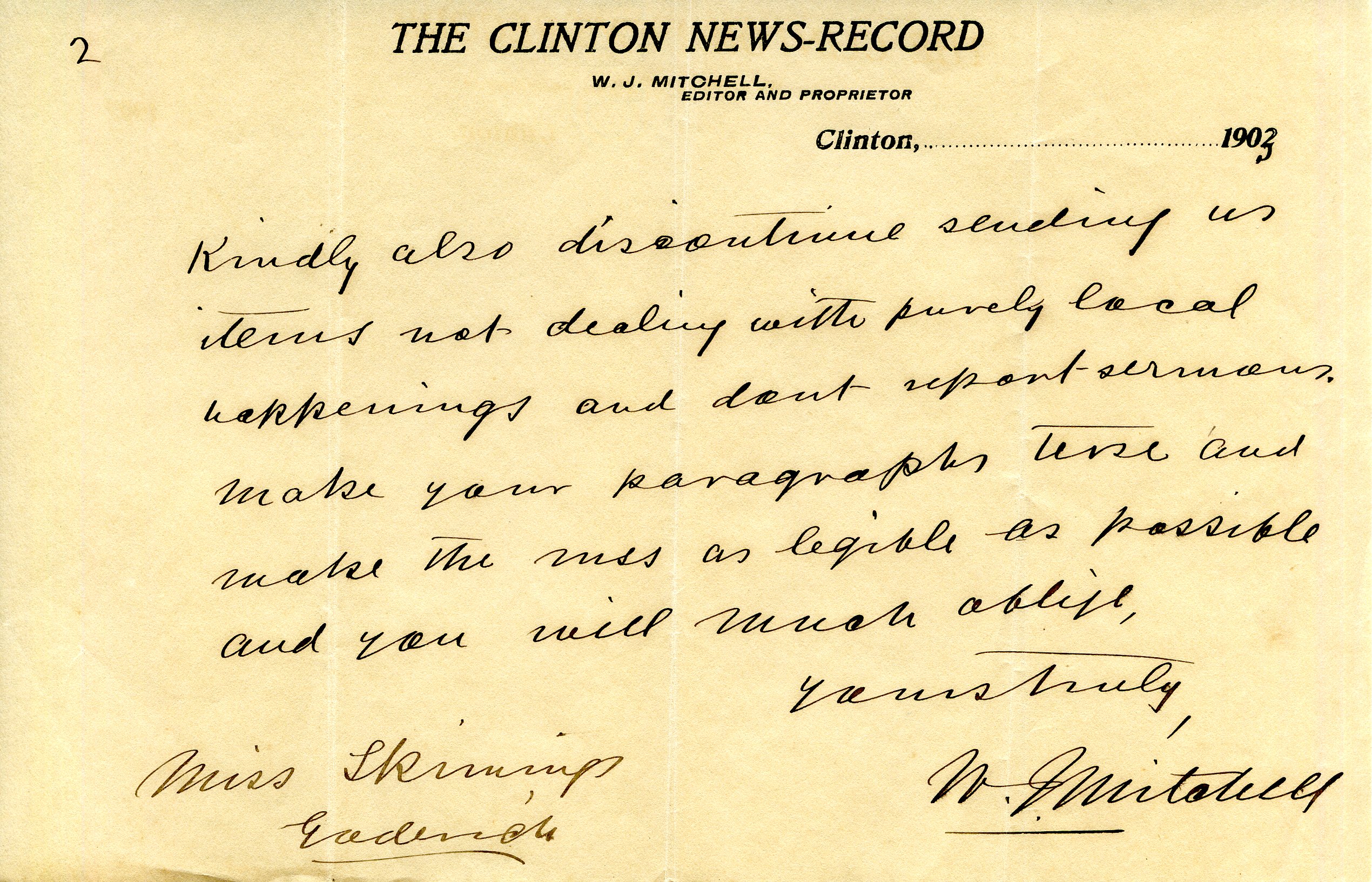

The archival fonds at the Huron County Museum consists of textual records and other material created and accumulated by Eloise A. Skimings during her career as a newspaper correspondent, teacher, poet, and composer in Goderich. During her lifetime she received much correspondence and letters, including thank-you letters, letters from her family & friends, news correspondence from her time at the Clinton News-Record, and payments for her poetry book. Some of these letters were written by well-known people of the time, from political figures to royalty. A finding aid can be found on the Museum’s website – Huron County Archives | Huron County Museum for researchers interested in reading more.

Images at left show two-page correspondence from our collection written Jan. 27, 1903 from Clinton News-Record Editor W.J. Mitchell. The full letter reads:

Dear madam,

On installing the typesetting machine in my office I sent you a circular drawing attention to the fact that copy for the machine operator must be written wide and legibly, you have forgotten that – and your copy has to be gone over and re-written which means a loss of time that I cannot afford.

Kindly also discontinue sending us items not dealing with purely local happenings and don’t report sermons. Make your paragraphs terse and make the ___ as legible as possible and you will much oblige, Yours truly, W. Mitchell

On the occasion of Eloise’s 80th birthday, it was “under consideration a proposal to mark” her 80th birthday with either “a concert or a public entertainment of some sort…doing honor to one who has for many years helped to keep Goderich before the world” (Goderich Signal Star, Thursday, May 8, 1919).

Eloise died at House of Refuge in 1921 and is buried at the Maitland Cemetery in Goderich, ON. Her death notice was published in the Clinton News-Record, April 14, 1914. From the digitized collection of Huron’s historical newspapers.

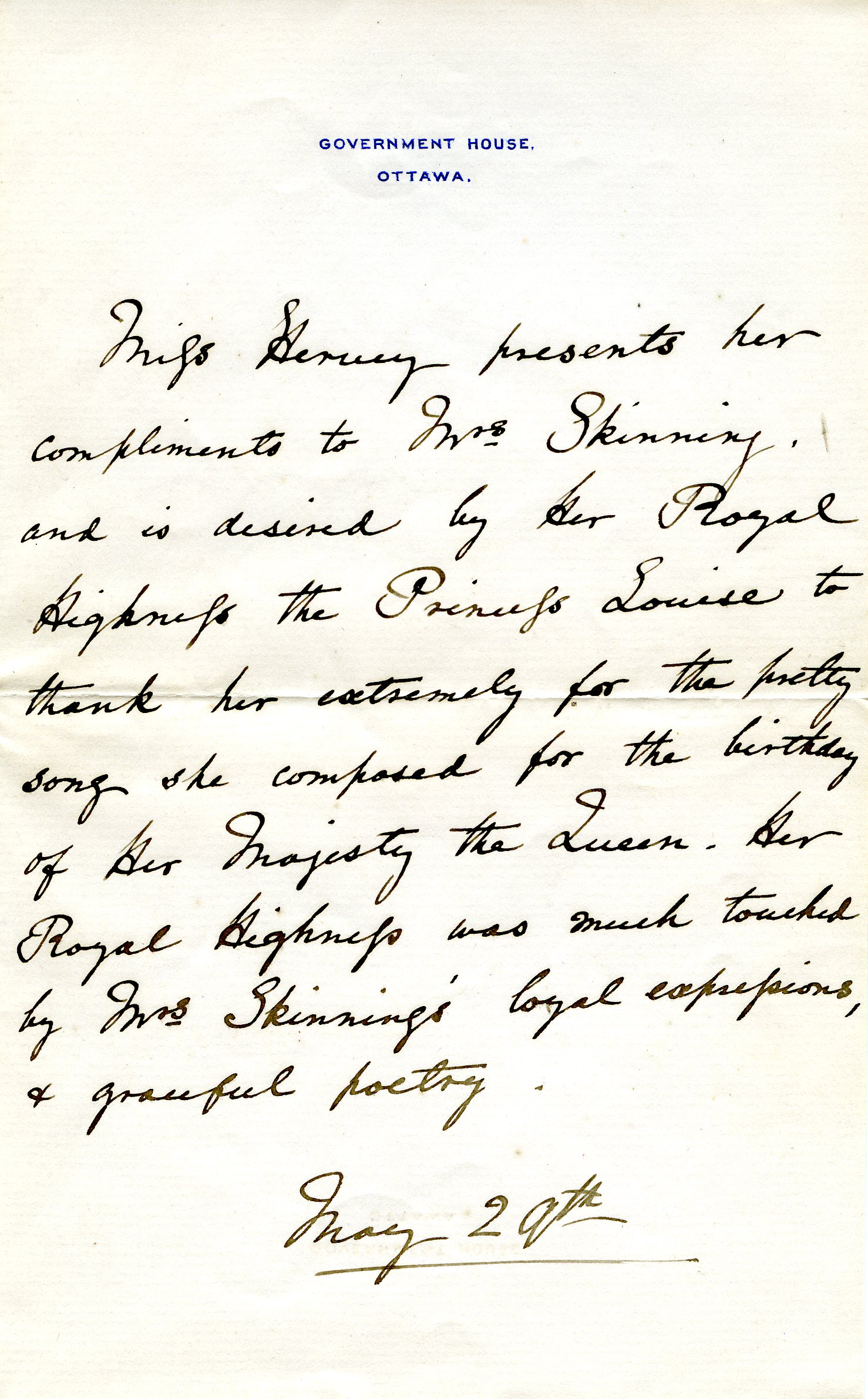

Princess Louise Margaret was the Duchess of Connaught & Strathearn and Viceregal consort of Canada while her husband Prince Arthur was Governor General from 1911 to 1916.

The full letter at left reads:

“__ presents her compliments to Mrs. Skimings, and is desired by her Royal Highness the Princess Louise to thank her extremely for the pretty song she composed for the birthday of Her Majesty the Queen. Her Royal Highness was much touched by Mrs. Skimings’ loyal expressions and graceful poetry.”

Mamma’s Bench, at right, once belonged to the Skimings family. Written on the bottom reads: “This cradle originally belonged to the Skimings family of Goderich, Ont. Eloise A. Skimings, the poetess of Lake Huron and her two brothers was rocked in this cradle. May good luck fall on all children rocked in it. Gavin Green.” Currently on display in the Stories from Storage exhibit. 2019.0037.001

by Amy Zoethout | Apr 12, 2023 | Archives, Blog, Collection highlights

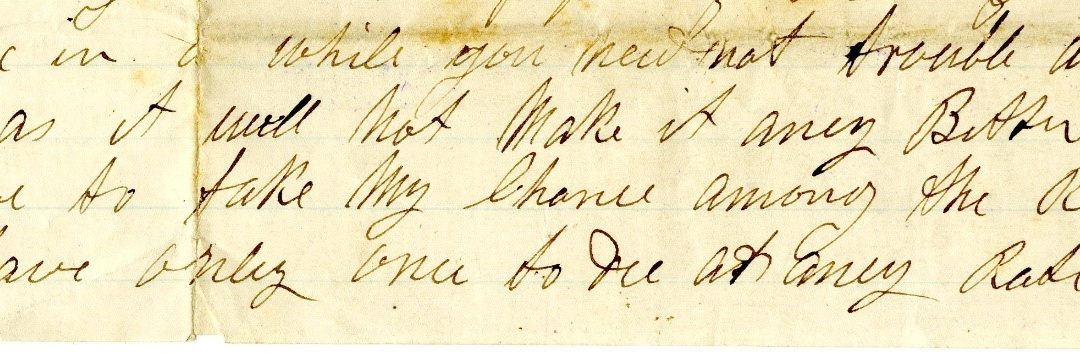

“I shall have to take my chance amongst the rest. I have only once to die at any rate.” – excerpt from a letter written by Joseph Hodskinson, March 29, 1862

The American Civil War doesn’t usually come to mind when thinking about Huron County history, but a recent donation to the Huron County Archives reveals the devastating impact the war had on a Brussels family.

Joseph Hodskinson immigrated to Canada from Scotland around 1851 with his wife Margaret and daughter Celina. The family settled in the Brussels area where Joseph worked as a farmer before he joined the Civil War. It remains unknown why Joseph chose to leave his family in Canada to join the fight in America, but what is known is he would never return home.

The American Civil War was fought between the Union (the North) and the Confederacy (the South – formed by states that had seceded) from April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865. According to Wikipedia, “the central cause of the war was the dispute over whether slavery would be permitted to expand into the western territories, leading to more slave states, or be prevented from doing so, which was widely believed would place slavery on a course of ultimate extinction.”

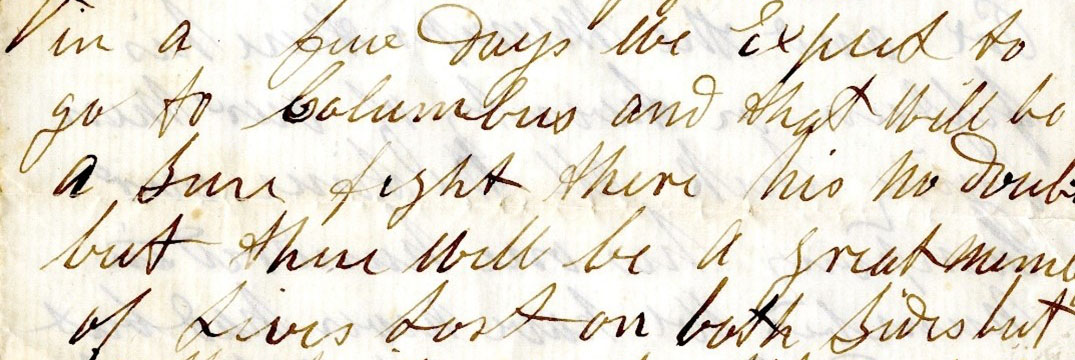

“We expect to go to Columbus and that will be a sure fight. There is no doubt but there will be a great number of lives lost on both sides.” – excerpt of a letter written by Hodskinson on Jan. 24, 1862

Between 1862 and 1863, Joseph wrote several letters home to Margaret and Celina, describing the horrors of war. In the first winter of the war, in January 1862, he shares the great deal of sickness that hit the soldiers, including measles, small pox and mumps. In a letter home on March 1862, he describes three days of fighting at the Battle of Fort Donelson and noted that “It is the providence of the Lord that I am amongst those that was saved on the 13th Feb….the morning after the battle the field was a fearful sight. You might almost walk on dead bodies for a long distance.” A letter home on June 12, 1862, reveals that “We only have about 300 men remaining out of 1000 since I joined the army.”

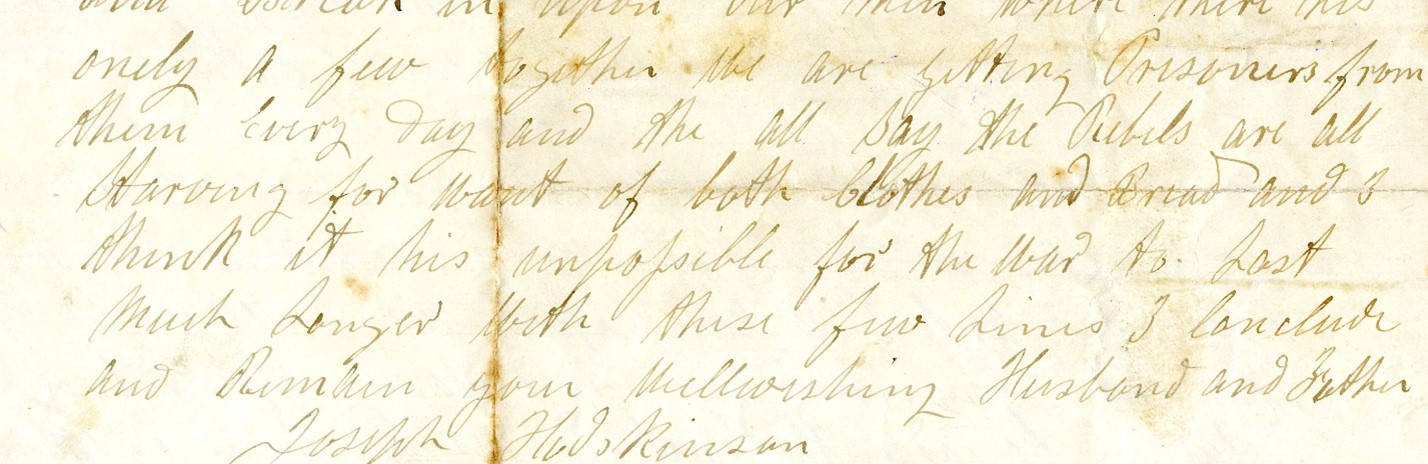

We are getting prisoners from them every day and they all say the Rebels are all starving for want of both clothes and bread and I think it is impossible for the war to last much longer.” – excerpt from a letter dated Jan. 2, 1863

The war would continue for two more years, but Joseph would not see the end of the war, nor would he make his way home to his family in Brussels. He died later that year.

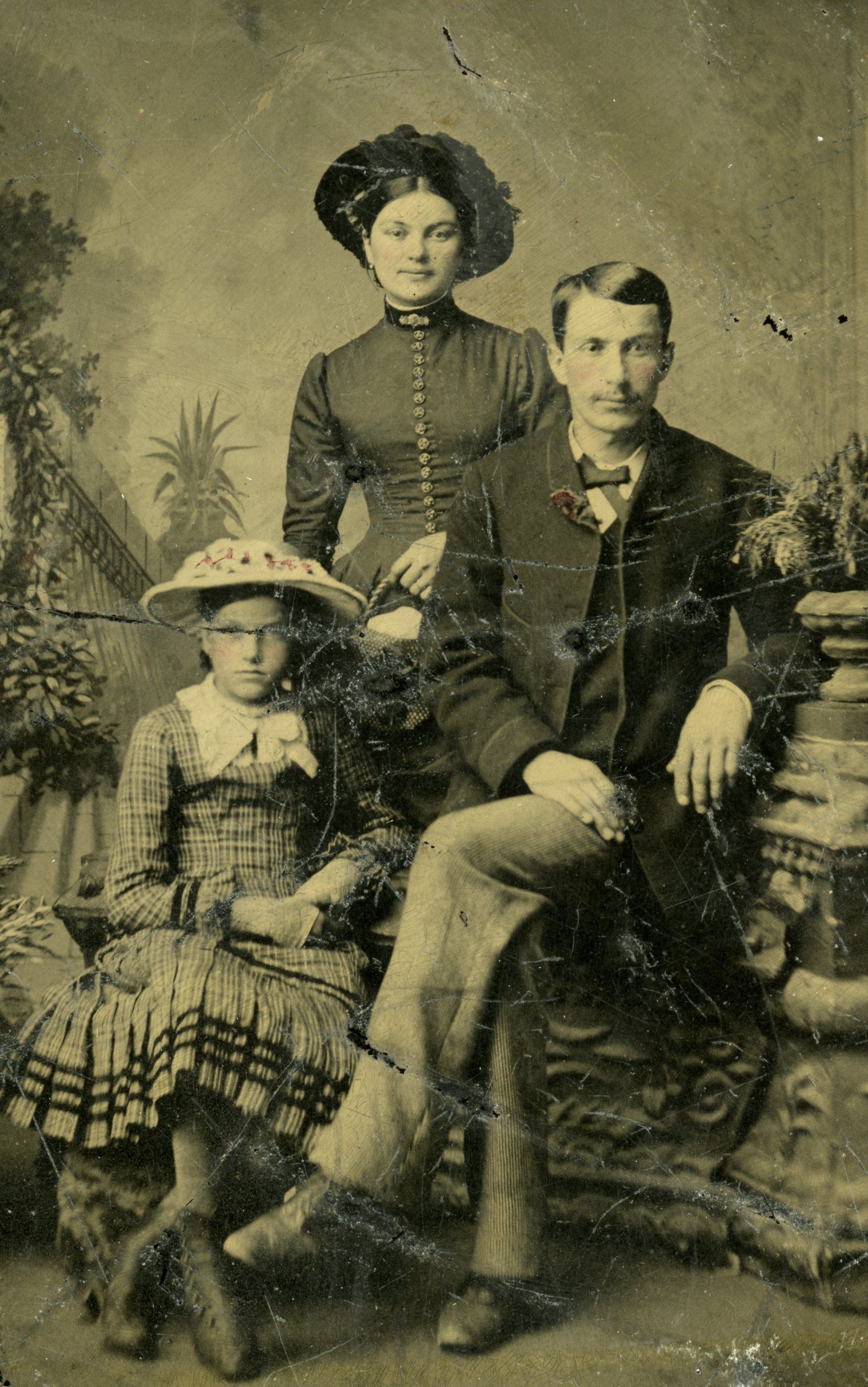

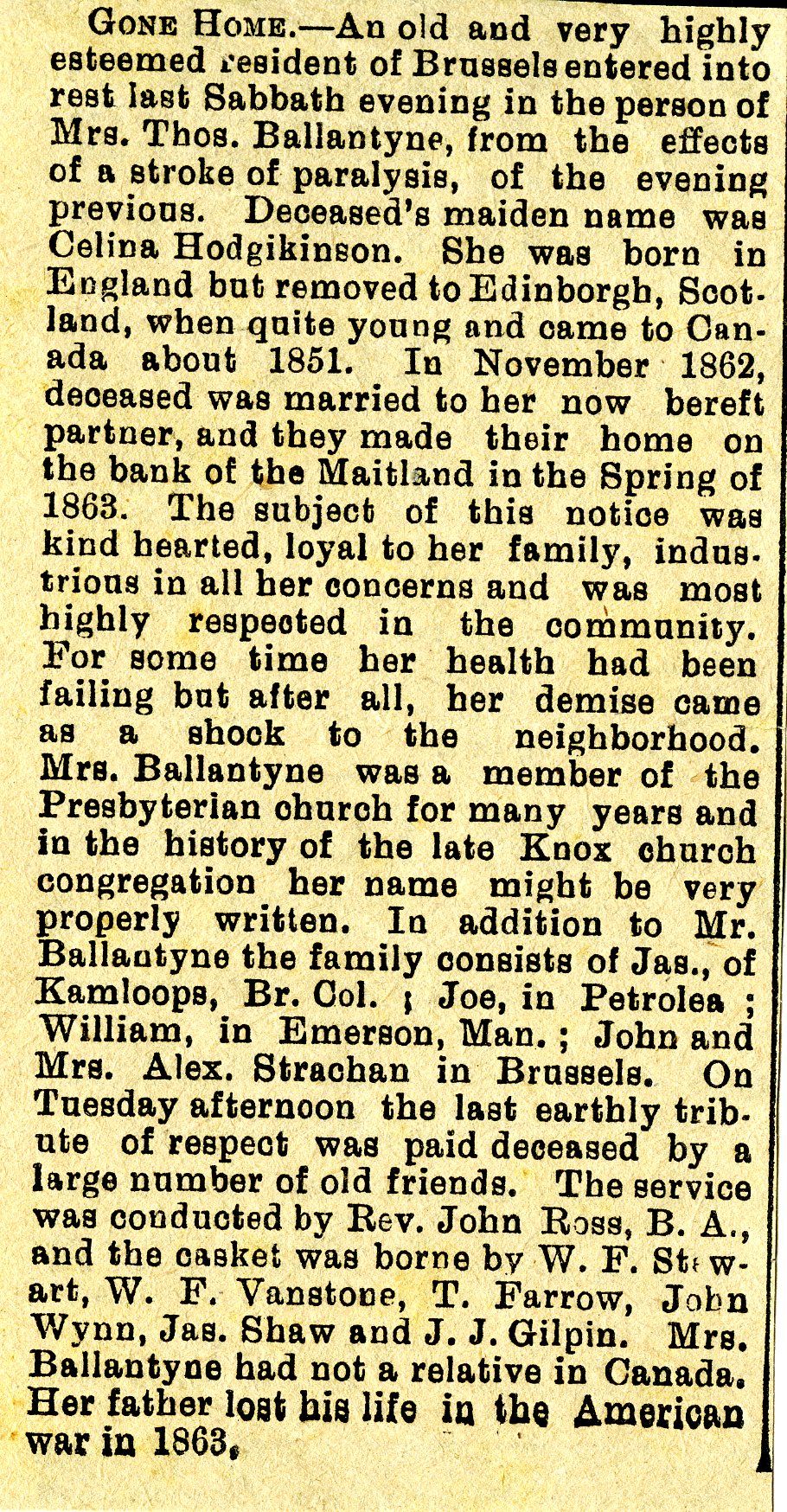

After Joseph’s death, Margaret and Celina remained in the Brussels area. Celina married Thomas Ballantyne in the fall of 1862 and the couple made their home on the bank of the Maitland River in the spring of 1863. The home is pictured above with the family sitting on the front porch around 1892. Shown here, from left to right, are Jack Ballantyne, Thomas Ballantyne, Celina Ballantyne holding Bill Strachan, Margaret Hodskinson, Annie and Alex Strachan, and Jenny and Joe Ballantyne.

Celina and Thomas had a daughter named Annie who married Alexander Strachan in Brussels in 1889. The couple owned a dry goods store in the village.

The Huron County Museum would like to thank Ann Scott and Marion MacVannel for their recent donation of these letters and family photographs to the archival collection. Joseph was Ann’s three times great grandfather. If you are interested in learning more about our research services or making a donation to our collection, contact the Huron County Archives to arrange an appointment.

by Sinead Cox | Nov 10, 2022 | Archives, Blog, Investigating Huron County History

According to the Criminal Code of Canada, “a female person commits infanticide when by a wilful act or omission she causes the death of her newly-born child.” Using local resources, student Kevin den Dunnen explores local cases of infanticide in the late 19th and 20th century (the period for which Gaol records are readily available), and the contemporary attitudes towards this act at home and abroad.

Through the 19th and 20th centuries, Huron County newspapers printed cases of infanticide, or the act of killing an infant, allegedly taking place in other countries and cultures. These articles often framed this the context of the supposed inferiority of cultures without the influence of Western Christianity. (1) However, the prevalence of infanticide in Huron County and surrounding areas during this same time period disproves any claims of cultural immunity to infanticide in southwestern Ontario’s Christian-dominated communities.

There are many social factors that contributed to the infanticides that occurred in Huron County. In the 19th and 20th centuries, a birth outside wedlock threatened an unmarried woman’s status in society. Many known infanticide cases in Huron County involved these young, unmarried women. Contributing to the devastating decision to commit infanticide was the lack of local social services available to single women needing help to provide for their child. As such, infanticide has been present in Huron County for much of its history.

The story of a Huron County woman called Catherine and her child exemplifies many of these themes. Catherine was a 30-year-old servant and unmarried woman working in Goderich Township in 1870. She had gone to her doctor that year claiming her body was swelling. The doctor suspected that she might be pregnant, but Catherine did not agree. Later on, her employer came home to find some of her work unfinished and could not find her. Upon searching, they found her sitting in a privy. After telling her to leave the privy several times, Catherine went to the house. Upon inspection of the privy the next morning, the house-owner and a doctor found a dead child in the privy vault covered by paper and a board. In his subsequent report, the coroner believed that the baby was born alive. (2) Upon first reading, this story appears to be a cold-blooded case of infanticide, but the reality of the society around Catherine makes the situation far more complex.

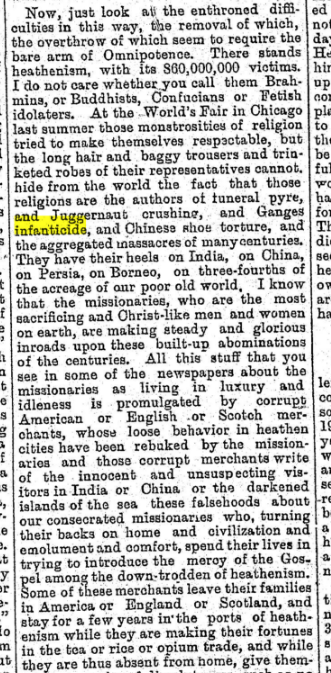

Turn of the 20th century newspapers in Huron County printed or reprinted articles from larger news agencies about non-Christian societies in India, China, and Hawaii and touted their supposed propensity of infanticide. These stories promoted the positive influence of Christian conversion outside of Canada, even though infanticide was also a local issue. Figure 1 is one such article from The Exeter Times, published on Feb. 1, 1894. This article states that the work of missionaries converting foreign societies to Christianity would “introduce the mercy of the Gospel among the down-trodden of heathenism.” The uncredited author claimed non-Christian cultures frequently committed infanticide but stopped when they converted to Christianity. (3) There is an apparent hypocrisy in these newspapers portraying other societies as uncivilized while the same issues were happing contemporaneously in their own Ontario communities. Figure 2 shows an article from The Brussels Post, dated Nov. 20, 1902. In this article, the author argues the need for laws restricting the distribution of alcohol. They state that such opportunities to change society are “the call of God” whose influence had already “conquered great evils, such as infanticide.” Yet, infanticide still occurred in the paper’s own region.

How prevalent an issue infanticide was throughout Huron County’s history is difficult to know, because many cases likely went unreported. A large proportion of the known cases involved single mothers of illegitimate children. However, some scholars suggest that more cases of undocumented infanticide frequently occurred in Western societies. These theories argue that hidden infanticide by married couples might partly explain changing gender ratios in select western societies. They claim this was a way of tailoring gender to fit family needs, like wanting males to help with farming. (4) Single women living and working away from their families would face greater difficulties concealing a birth without detection. Hidden infanticide drew attention from journals like the Upper Canada Journal of Medical, Surgical and Physical Science in 1852. This journal argued that women should have to register their children immediately after birth to lessen the chance of hidden infanticide. (5) This call for registration suggests that the journal suspected or knew of infanticide cases where the mother did not register their child to hide its birth. This research indicates that communities like Huron County could have many cases of infanticide that county records do not include.

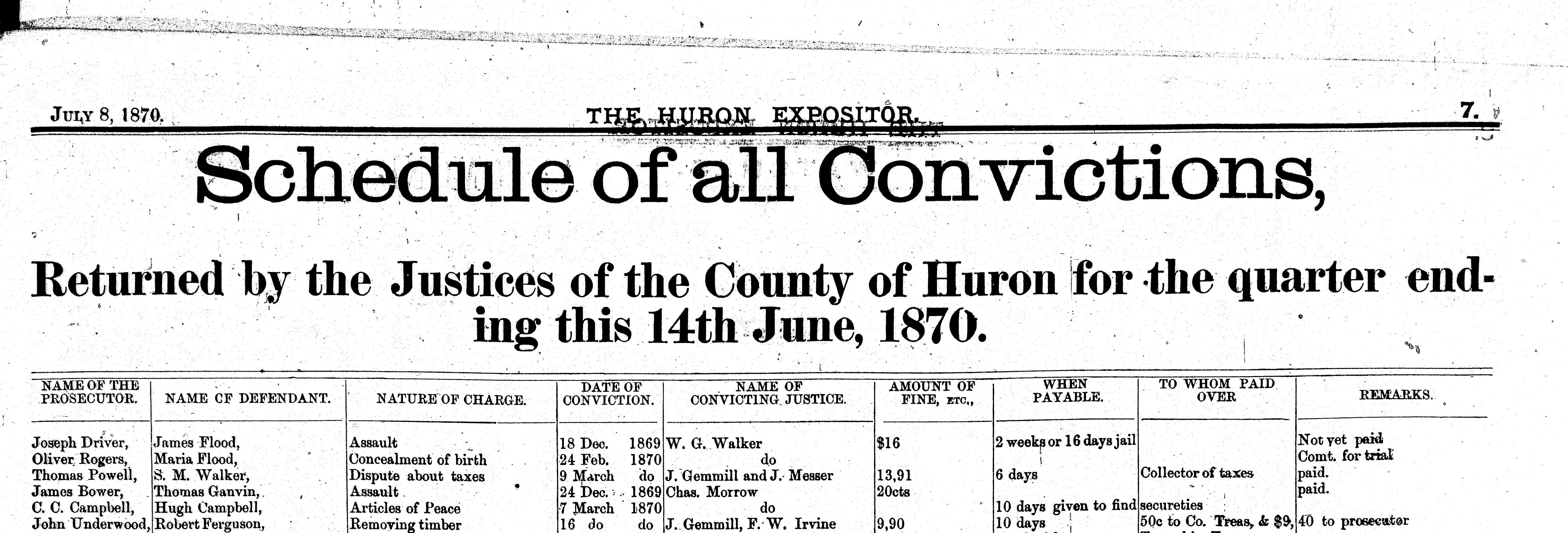

One record that is available for study is the “Huron County Gaol Registry.” The portion of the Registry currently available for research includes entries for every person who stayed at the Gaol from 1841-1922. There are at least 12 cases that list infanticide, concealment of birth, child exposure, or a related charge as the reason for committal (Figure 3 and 4). While not a staggeringly high number, these records only include the people sentenced to gaol for allegedly killing their infant or related crimes. If they were not apprehended or not committed to jail, they would not appear in the registry. Additional cases do appear in the local newspaper accounts (Figure 5) and coroner’s inquest records , including Catherine’s story . The registry shows that the first prisoner committed for infanticide came to the Gaol in 1846 and that a prisoner was committed for procuring drugs for an illegal abortion in 1920. While not demonstrating frequency with complete accuracy, the registry clearly does indicate that infanticide and other crimes resulting from unwanted pregnancies occurred in Huron County throughout the entire period documented from 1841-1922. These instances of infanticide would increase when including the records of nearby counties like Middlesex, Bruce, and Perth, which also had reported infanticide cases during the same period. There was therefore no reason to look to other countries to find the circumstances that fostered infanticide: Huron County residents could see the evidence in their own towns and the surrounding counties.

Figure 1: “The Safe Arm of God,” The Exeter Times, 1894-2-1, Page 6

Figure 2: “Prohibition Notes,” The Brussels Post, 1902-11-20, Page 4

Figure 3: The Huron Expositor, 07-22-1881, pg 5.

Figure 4:The Huron Signal, 06-10-1887, pg 4.

Figure 5: The Huron Signal, 12-10-1880, pg 1.

Mothers faced most of the blame for infanticide from the legal system and contemporary journalists for reported cases. However, this viewpoint often neglects to consider both the devastating judgements placed upon these women for their unwanted pregnancies, and the lack of support available to help struggling mothers. Of the cases involving infanticide, concealment of birth, or abortion found in the Huron County newspapers and Gaol records, a large number involve young women under 25 years old and illegitimate children (the offspring of a couple not married to each other). For example, a case from 1864 involves a 15-year-old unmarried female servant; a case from 1877 involves a 22-year-old single female servant; a case from 1880 involves a 17-year-old female servant. As servants, these women were dependent on wage labour. With the birth of a child, the woman would have to give up employment to care for the baby, as without the security of legal marriage the father would often refuse any support. Her ability to care for herself, let alone the child, declined greatly after giving birth. In addition, women faced religious and societal pressures to remain chaste until marriage. Bearing an illegitimate child proved to society that a woman was unchaste. (6) Women who gave birth to illegitimate children, no matter the circumstances of their conception, would face harsh judgement from their communities, which could impact their ability to find new work or to be married. These women with illegitimate children immediately became outcasts. This happened because Christian societies at the time judged much of a single woman’s morality and value according to her chastity. (7) As such, women of this period faced significant social judgement if they had an illegitimate child. The idea of concealing the child’s birth may have appeared to be the only choice for single mothers hoping to retain their ability to earn a living, maintain their place in society and avoid becoming an outcast, which could lead to cases of infanticide and child abandonment.

The lack of available social services in Huron County before the 20th century could also factor into these cases of infanticide. Before Huron County’s House of Refuge opened near Clinton in 1895, the only municipal building available for social services was the Huron County Gaol. There was no local lying-in hospital or home for unwed mothers. During this period, the Gaol often housed the elderly, destitute, and sick. Some lower tier municipalities made the choice to commit unwed mothers to gaol to give birth, and multiple women would have their babies behind bars at the Huron Gaol. This was an inexpensive way to house the mother and child until such a time she could return to the labour market. A young woman faced with the birth of an illegitimate child in Huron County would therefore have little support and few options available should she struggle to care and provide for her baby, and may have to bear the stigma of being committed to gaol regardless of committing a crime.

While newspapers like The Exeter Times and Lucknow Sentinel reprinted articles featuring infanticide as a cautionary tale to criticize and condemn outside cultures and to promote the positive influence of western Christianity, infanticide remained prevalent in their own communities. Stories like that of Catherine demonstrate the difficult circumstances that sometimes drove women to commit infanticide. Having an illegitimate child immediately lessened the perceived status and life options of a young woman in respectable Christian Southwestern Ontario society. Also contributing to the devastating decision by some of these young women to commit infanticide was the lack of social services available to help them provide for a child. As such, infanticide was not a conquered issue for the residents of Huron County in the 19th and early 20th century.

Sources:

- (1) Nicola Goc, Women, Infanticide, and the Press, 1822-1922: News Narratives in England and Australia (New York, NY: Routledge, 2016), 28.

- (2) Coroner’s Report #365 Huron County Archives, Unnamed baby of Catherine J.

- (3 “The Safe Arm of God,” The Exeter Times, February 1, 1894, p. 6.

- (4) Gregory Hanlon, “Routine Infanticide in the West 1500-1800,” History Compass 14, no. 11 (2016): pp. 535-548, https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12361, 537.

- (5) Kirsten Johnson Kramar, Unwilling Mothers, Unwanted Babies: Infanticide in Canada (Vancouver, BC: UBC Press, 2006), 97.

- (6) Nicolá, Women, Infanticide, and the Press, 21.

- (7) Nicolá, Women, Infanticide, and the Press, 21.

Further Reading

Find an index of coroner’s inquests on our Archives page (scroll to the bottom to find indexes and finding aids).

Find more stories from Huron’s past through a search of Huron County’s historical newspapers online!