by Sinead Cox | Oct 11, 2018 | Blog, Exhibits

Meagan Barnhart is a Mississauga Ojibwe (Anishinabe)/ Cayuga (Haudenosaunee) artist from McKerrow, Ontario and a Cultural Heritage Conservation and Management student at Fleming College. An exhibit featuring Meagan’s 7-piece bead embroidery series inspired by K-pop group BTS (as well as 10 smaller beaded flowers), is temporarily on display at the Huron County Museum.

Meagan Barnhart is a Mississauga Ojibwe (Anishinabe)/ Cayuga (Haudenosaunee) artist from McKerrow, Ontario and a Cultural Heritage Conservation and Management student at Fleming College. An exhibit featuring Meagan’s 7-piece bead embroidery series inspired by K-pop group BTS (as well as 10 smaller beaded flowers), is temporarily on display at the Huron County Museum.

Curator of Engagement & Dialogue Sinead Cox interviewed Meagan to find out more about her creative process and the development of her technique. You can see Meagan’s stunning work at the museum until February, 2019.

When did you start beading? What made you want to start?

I started beading when I was really young. My mother beaded a lot and she often got me to sort out beads that were mixed together in a cookie tin. She first started teaching me by doing bead loom work and simple jewellery. However, once her eyes started to bother her while she beaded and circumstances changed in our family, beading went out of my mind. It wasn’t until many years later in my late 20s that my passion was reignited when I did some volunteer work at the Woodland Cultural Centre. For one of the months I was there I worked in the Education department – I didn’t have much knowledge that I could offer unfortunately, so I was asked to do some beadwork for game prizes. From there, I moved to Gatineau, Quebec where I got an internship at the Canadian Museum of History for Indigenous, Inuit, and Metis peoples who are pursuing training in museum work (Aboriginal Training Program in Museum Practices); it was there where I learned how to do bead embroidery, which I commonly do now.

I was influenced by many things: my surroundings and colours. I was exposed to a lot of beadworks at the museum, and I thought to myself that I would love to be that good and it excited me at the possibilities of being able to create something beautiful and calming. I was not only influenced by the beadworks but colours and emotions as well.

The work on display is inspired by the K-pop (South Korean pop) band BTS-can you explain when you  became a fan of BTS, and why they are such inspirations for your work?

became a fan of BTS, and why they are such inspirations for your work?

The colours in their music videos, [their] lyrics, and emotions represented in their music were great inspirations to me. I have known the group since they debuted, and I can say I was always a fan of theirs, but it wasn’t until around the time I started beading that their journey sunk into my mind – their music and videos often resonated with me and a lot of them felt like a familiar dream and the messages in their music were ones that I never got when I was young and wish I had. [BTS are advocates for youth and loving yourself; they recently addressed the United Nations regarding equipping young people with self-confidence to make a global impact]

For me, at this moment, beading and BTS kind of go hand-in-hand because it was when I started beading in 2016 [that] I also began to call myself an ARMY (Adorable Representative MC for Youth)–their fandom name.

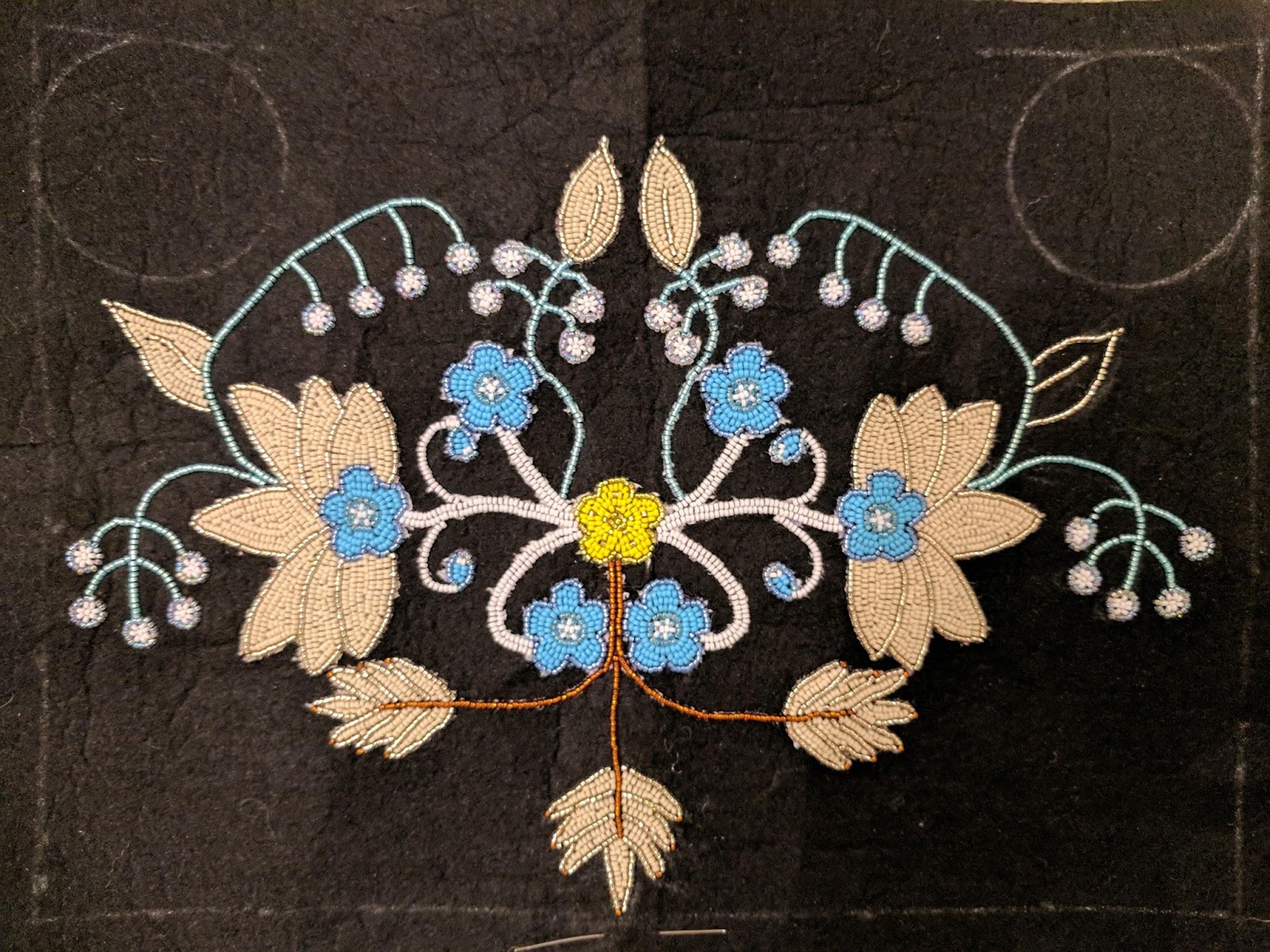

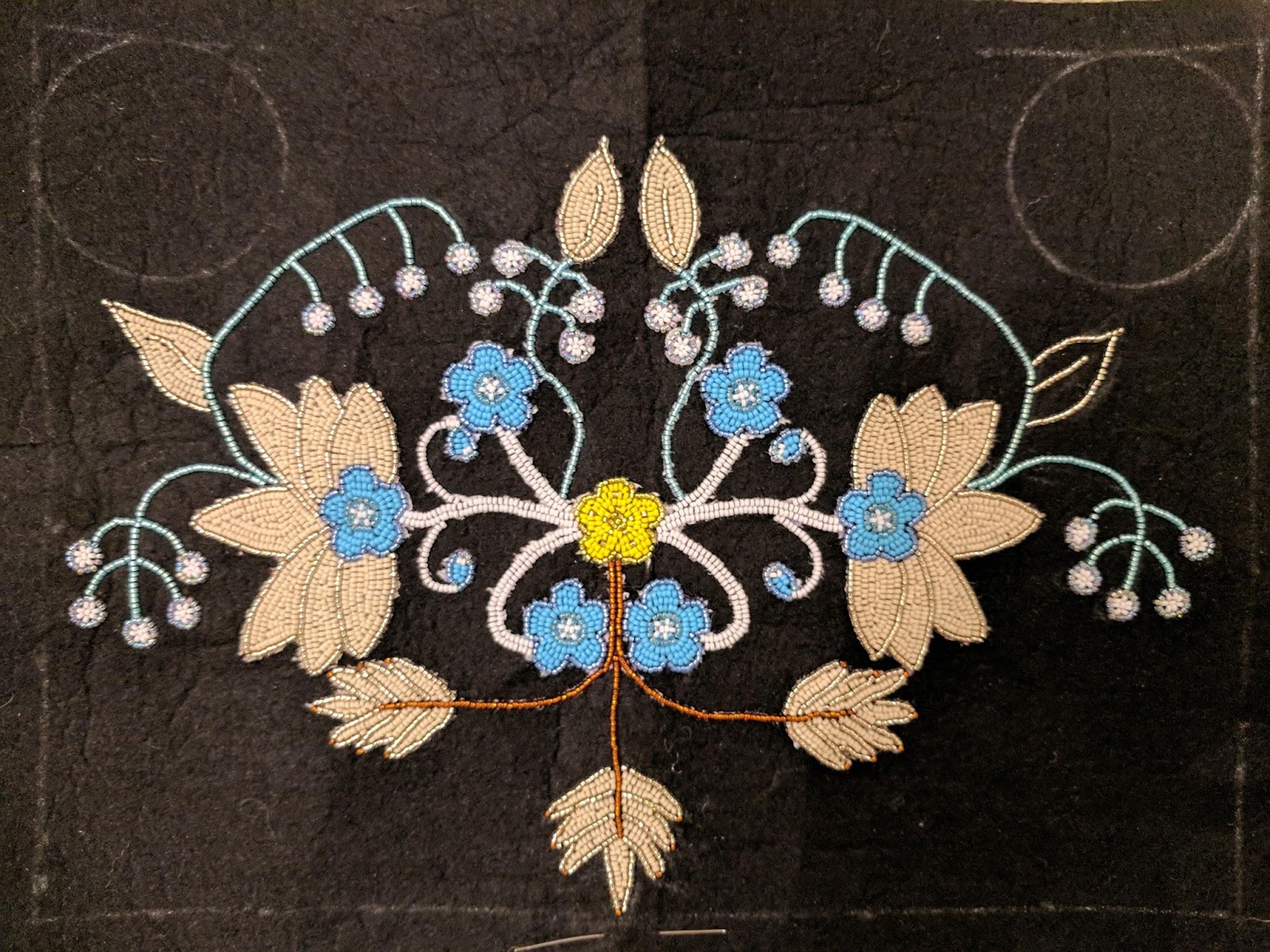

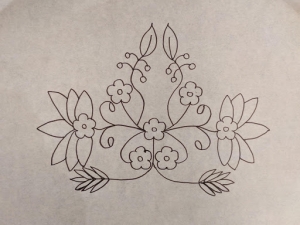

Meagan’s first embroidery piece!

How has your technique/artistry evolved?

I really still use the same materials I always have…only they are a bit better quality now. I would like to experiment on more types of materials, but I am only new to my beading (almost two years now, but I still consider myself new and learning). As of right now I don’t have any other beaders close to me to discuss new techniques or tips. So its slow learning, but I gradually pick up new techniques every once in a while – especially when I feel daring enough to step out of my comfort zone.

“Suga ~ Nevermind Colour Inspired Beaded Flowers”: Meagan’s first attempt at a raised beadwork in progress.

For example, my raised bead work: I [had] only been taught once how to do a raised beaded strawberry while working at the Woodland Cultural Centre, but [after] that…I felt comfortable with bead embroidery; I ventured on my own to try different techniques with raised bead work. I think I still need to practice a lot with this style and I would benefit greatly in the future having a friend or two around that I can discuss such things with.

When it comes to the evolution of my BTS colour inspirations, I started out small – using the colours to make single flowers instead of larger pictures with them.

This is my very first one:

This one was based off their “WINGS: You Never Walk Alone” album. It had two covers, I particularly liked the colours of their aqua and peach coloured album – unfortunately I didn’t have peach at the time, so I used a pink as a replacement. After I finished this one, I continued by doing 3 more for the albums, and one for each member inspired by their clothing they wore at some point within the music video “Spring Day”

Who taught you beading/how did you learn?

I learned how to bead embroider when I was at the Canadian Museum of History from a fellow intern friend who is Métis. Her sister is a beader and invited me to go [to] an evening bead workshop. Unfortunately, it was [so] far by bus to get to the workshop that I only was able to spend less than a half hour with them – and from then on was not able to continue going to the classes. However, this was enough time to teach me the basics and…me and my two fellow intern friends continued to bead on our lunch breaks.

Can you briefly take us through the process of designing the seven pieces in this series?

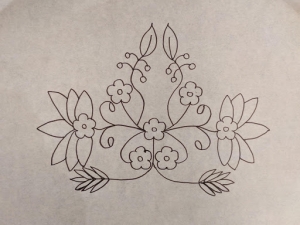

First I watched the Music Video, then I chose a scene that captured my attention. I then read the lyrics, analysed any imagery within the entire music video to get a sense of what the storyline was – if there was a book, or movie related to the music video or even the series that the music video is apart of (School Series, WINGS Series, Love Yourself Series), I’d read or watch then to get a sense of what the entire series was about…With [each] scene I choose, I pick the colours that were most dominant in the image and choose flowers based on them.

For the flowers, I often tried my best to try to use wildflowers of North America, specifically ones I’m most familiar with in Canada…I would research the meaning of the flowers or what their uses were – if I already knew what they represented or what they were used for, the better. I wanted to choose flowers that would tell a story – something that related to the music video, or BTS’s relationship with their fandom ARMY – especially since their bond is a lot stronger than I have ever seen between artist and fandom. From there I would develop a pattern. I often enjoyed the somewhat-symmetrical design; I say somewhat, because although it looks symmetrical, nothing is ever perfect, and neither are they, they don’t line up perfectly and they don’t have the same amount of beads on each side.

For the flowers, I often tried my best to try to use wildflowers of North America, specifically ones I’m most familiar with in Canada…I would research the meaning of the flowers or what their uses were – if I already knew what they represented or what they were used for, the better. I wanted to choose flowers that would tell a story – something that related to the music video, or BTS’s relationship with their fandom ARMY – especially since their bond is a lot stronger than I have ever seen between artist and fandom. From there I would develop a pattern. I often enjoyed the somewhat-symmetrical design; I say somewhat, because although it looks symmetrical, nothing is ever perfect, and neither are they, they don’t line up perfectly and they don’t have the same amount of beads on each side.

What kind of materials do you use?

I use 15/0 glass seed beads (for the bigger pictures to get more detail). For the singular flowers I mostly use 11/0 glass seed beads, but i mix them sometimes with 15/0 seed beads, 10/0 seed beads, and 11/0 delica seed beads. For the substrate I use 100% polyester felt (more recent ones are made with a stiff felt – as are the big pieces), and either nylon, polyester, and/or cotton thread (I prefer nylon and cotton over polyester for thread because they do not tangle as much), and a 16/0 beading needle. I draw on tracing paper and bead over it. Once the beading is done, I remove the paper as much as possible/visible.

How long did it take you to bead the pieces on display?

For the singular flowers, around 12 hours (it can be more or less depending on size and my familiarity with the pattern I am using), and for the larger pieces I would say around 150 hours (more or less, depending on the amount of difficulty and style). For the full series of the large pieces, the entire project took me a year, practically to the day. For the smaller flowers, that series has almost been a year long as well – I believe my year will be up in November. This year has been full of many projects (not just these ones), so that may have contributed to why these series took me so long to complete.

What’s the most difficult part of creating beadworks? Conversely, what’s your favourite part of the process?

Sometimes the amount of detail you want doesn’t show through, and you will never know until you start. There [were] a few times when I envision[ed] something, made it halfway through my design and had to alter something because it wasn’t working out the way I planned or it wasn’t looking the way I wanted it to. Eye strain is another difficult thing to control as well, especially when you are really focused.

One of my favourite parts is the relaxing feeling it gives me – it’s almost like meditation at times. I also really enjoy seeing the outcome of it all.

Do you have a favourite piece that you’ve created so far?

Each one has a particular place with me when it comes to the big ones [from the series] – However, I think my first one, Serendipity, holds a special place in my heart. It’s not my best one, but it is my first attempt at doing anything so ambitious. I also remember how much i loved that song and music video when it came out – I still do really. There was a lot in this music video that reminded me of what my dreams look like when I sleep, and my first thought was that I really wanted to capture that feeling by capturing the colours. When I look at it, I can see things that I could have done better – even with the story telling I have with the flowers, but instead, these flaws make me smile and i love it just the way it is.

“JIMIN ~ Serendipity Colour Inspired Beaded Flowers” Flowers are lily of the valley, buttercup and periwinkle. The two circles (unfinished in this image) represent the sun and moon.

[BTS member] Jimin is also my bias [a fandom term for preferred member of the group], so that may have something to do with my gentle lean towards Serendipity – it is his solo intro song that inspired me to do this series.

Is there a story or message you hope your work conveys?

Surround yourself with positivity – beauty, happiness, serenity, peace – appreciate your hard times, they will help you recognize the good in even the smallest form if you allow it to.

Where can people follow you & your work?

Instagram: @ojistah88

Twitter: @Ojistah

AMINO (ARMY and ARMY++): Ojistah

Meagan’s work will be on display in the museum lobby October 2018 through February 2019. All photos for this piece courtesy of Meagan Barnhart.

by Sinead Cox | Jul 18, 2018 | Exhibits

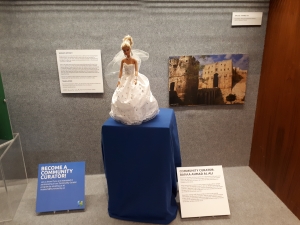

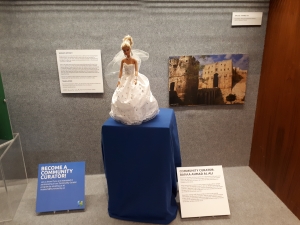

Sinead Cox, the museum’s Curator of Engagement & Dialogue, introduces the museum’s latest temporary exhibit, Community Curators: Newcomers (on display now).

From storage and display methods, to how and when we handle objects, museum staff endeavour to protect the artefacts entrusted to our care from the manifold dangers of shifting temperatures, chemical reactions, pests and damage–to preserve each and every artefact for future community access based on its unique needs. I encountered a new artefact-care dilemma recently however, when I had to think about the best way to preserve and protect an artefact’s existing smell while on display.

The 2018 participants for the museum’s recurring ‘Community Curators’ exhibit are both newcomers to Huron County. Instead of choosing an object from the museum’s collection like previous guest curators, they have very generously loaned an artefact of their own. Siham Mohammed of Wingham and Baraa Ahmed Al-Ali of Ashfield-Colborne-Wawanosh both fled with their families from war in Syria, and came to live in Huron County as sponsored refugees. I asked each volunteer curator to select an object or objects that related to their personal story or home country, and to translate the name of that object into English and their first language (Kurdish for Siham, Arabic for Baraa).

Because her family had few belongings when they came to Canada, twelve-year-old Baraa used her creativity to design and customize a doll’s dress to represent a typical Syrian wedding gown. Baraa’s handmade design evokes happy memories of family weddings in Syria and Lebanon when all of her brothers and sisters were still together.

Siham loaned two scarves that she has carried with her since she left Aleppo with her husband in 2011, first fleeing to Turkey for safety and eventually being matched with her new home community in Wingham. The scarves belonged to Siham’s mother, who she hasn’t seen since she left Syria. Although the scarves have lovely floral patterns, Siham doesn’t wear them in Canada as fashion accessories; she keeps them as keepsakes that remind her of her family still in Syria. The scarves remarkably still smell like her mother: strongly of jasmine perfume and more faintly of cigarette smoke.

Siham loaned two scarves that she has carried with her since she left Aleppo with her husband in 2011, first fleeing to Turkey for safety and eventually being matched with her new home community in Wingham. The scarves belonged to Siham’s mother, who she hasn’t seen since she left Syria. Although the scarves have lovely floral patterns, Siham doesn’t wear them in Canada as fashion accessories; she keeps them as keepsakes that remind her of her family still in Syria. The scarves remarkably still smell like her mother: strongly of jasmine perfume and more faintly of cigarette smoke.

The museum is very honoured to temporarily host such significant artefacts, and I knew it would be important to preserve the distinctive and familiar odour that adds so much personal value to the scarves. After consulting with our Museum Technician, Heidi Zoethout, we decided to encase each scarf individually in smaller plexi-glass boxes in the larger display case. Visitors will just have to imagine the strong flowery scent, and maybe think about what home smells like to them.

There are many objects donated to the museum’s permanent collection with similar stories: precious items carried from Ireland, England, Scotland, Germany, Holland or India brought with immigrants starting new lives in the presence of something that evokes the familiar sights, sounds, feelings, or scents of home. When the journey demanded that other possessions be sold or left behind, these were the items that remained. And that is really why, in my estimation anyway, it matters to pay attention to and try to preserve the texture, vibrancy, and integrity of these objects as much as we can—their value isn’t always something that you can put a price tag on, but it can encompass a sense of the past that you can see, touch, hear, taste or sometimes even smell.

To learn more about our curators’ stories, you can visit the Community Curators exhibit in the upper mezzanine of the Huron County Museum this summer. If you would like to be a community curator, contact us at museum@huroncounty.ca.

by Sinead Cox | Nov 11, 2017 | Exhibits, Investigating Huron County History

From Nov. 21st, 2017 to March 2018, the museum’s temporary Hot off the Press: Seen in the County Papers exhibit will look behind the headlines to the men, women and changing technologies that have brought Huron’s weekly papers to press for over almost 175 years. In this Remembrance Day post, Sinead Cox, Curator of Engagement & Dialogue and curator of the upcoming exhibit, examines the life of one Huron newsman who was also a veteran of the First World War, and follows the story of his return from service via mentions in the local weekly papers.

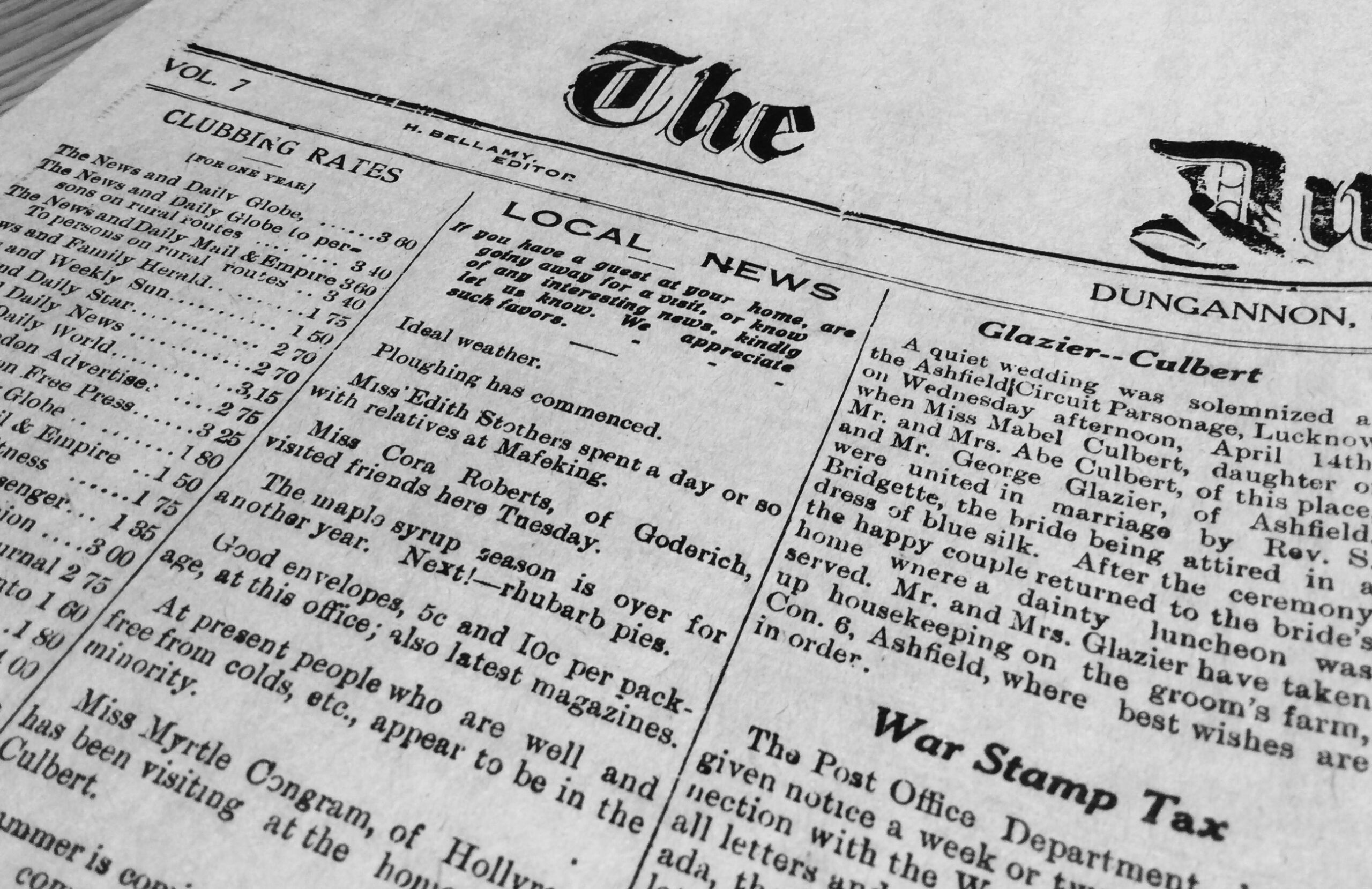

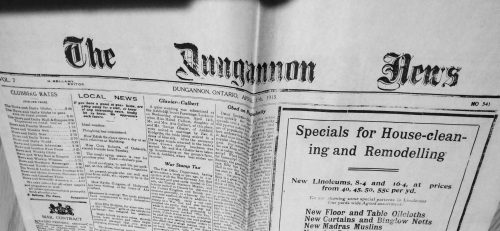

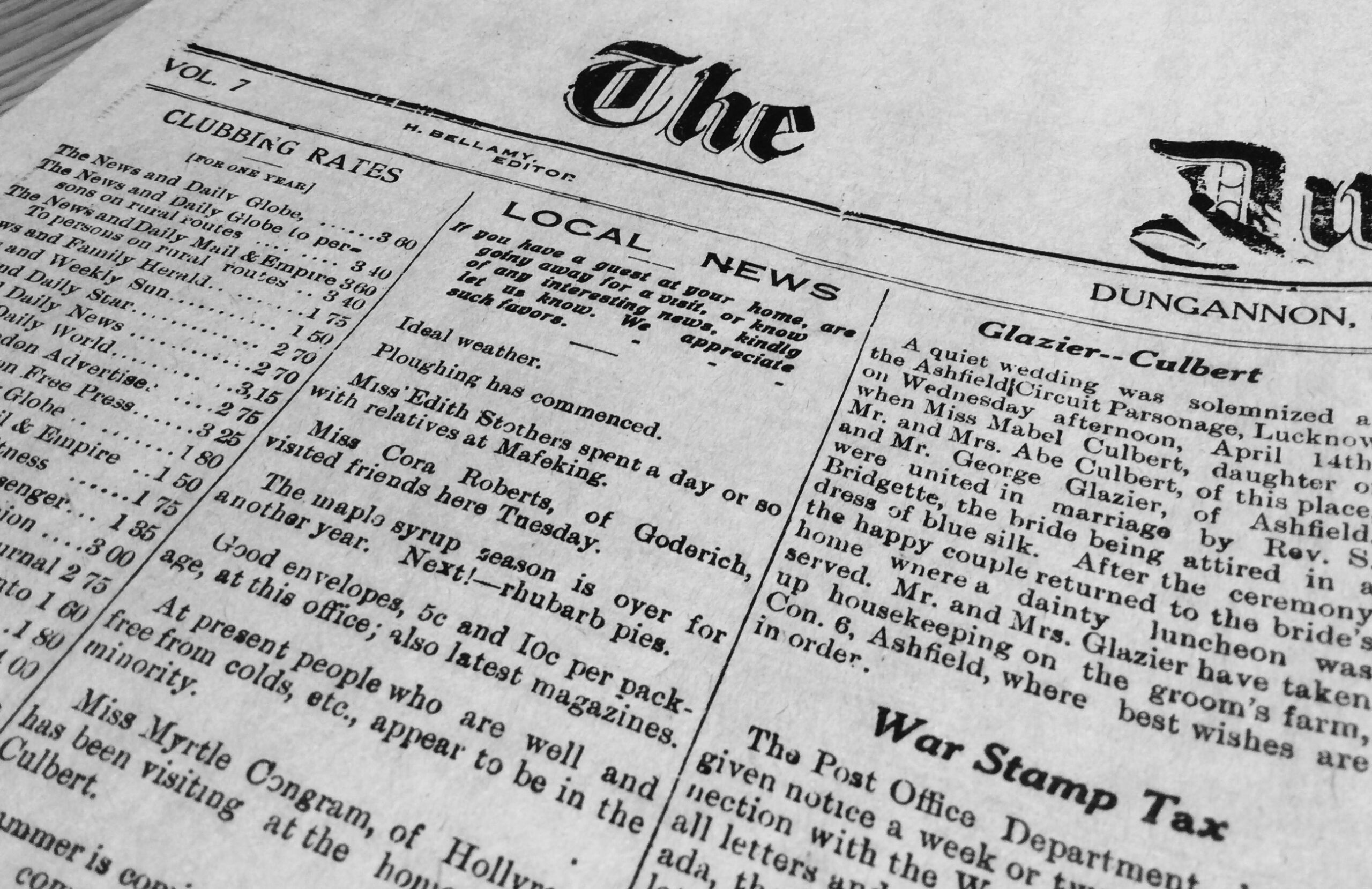

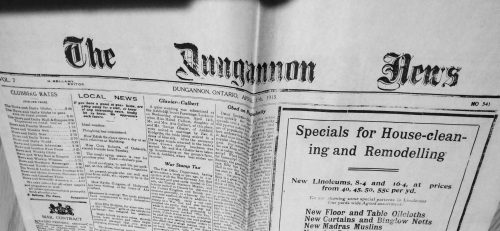

The Dungannon News, 1915-04-15

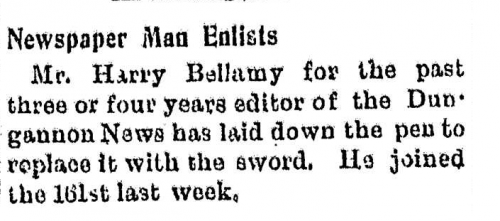

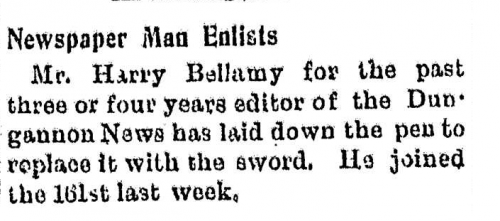

From my research into Huron County’s newspapers, it’s clear that a lot of effort, long hours and personal sacrifice often went into putting a paper to press and ensuring the latest edition reached local subscribers’ doorsteps on time. There were few excuses that could justify a late paper on the part of its proprietors: perhaps broken equipment, the precedence of a contracted print job (ie printing election ballots), adverse weather, public holidays, or even the rare editor’s vacation. One of the most notable reasons to stop the presses, however, occurred in 1916 when The Dungannon News ceased publication entirely because its editor enlisted to serve overseas with Huron’s 161st Battalion.

Pte. Bellamy’s attestation paper. You can access his full personnel file at: http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/

Born in 1891 in Blanshard Township, Perth County, Charles Arthur Harold “Harry” Bellamy had moved to Huron by 1908 when his step-father, Leslie S. Palmer–a former staffer at the St. Marys Journal and owner of the Wroxeter Star–founded The Dungannon News. His sisters, Amelia and Luella Bellamy, also worked locally as operators for the Dungannon telephone office. When his mother and step-father moved to Goderich in 1914, Harry became both editor and publisher of the News while still in his early twenties.

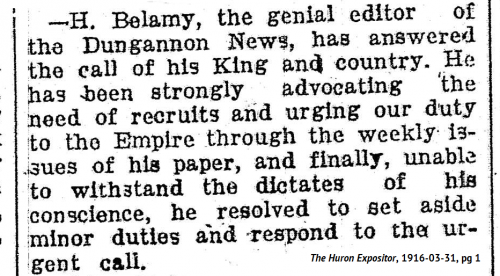

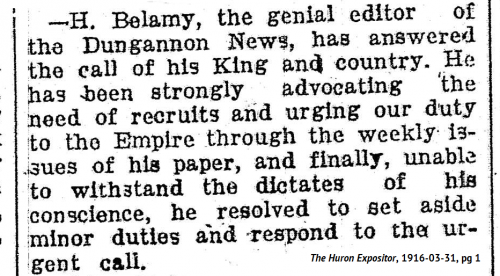

As editor, H. Bellamy strongly supported Canada’s involvement in the Great War within the pages of his publication, and by March of 1916 had decided to enlist himself. At only 24 years old, and a newlywed of less than two years with his wife, Annie Pentland of Ashfield Township, Editor Bellamy signed up to serve with the Canadian Expeditionary Forces at Goderich. With the departure of its proprietor, The Dungannon News merged with Goderich’s Tory weekly, The Star, and the newsman became the news as fellow editors praised Harry Bellamy’s decision in the columns of their papers.

The Wingham Advance, 1916-03-23, pg 5

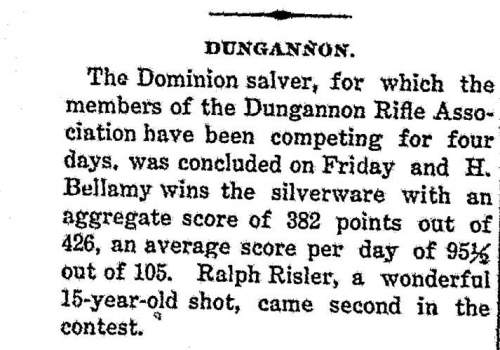

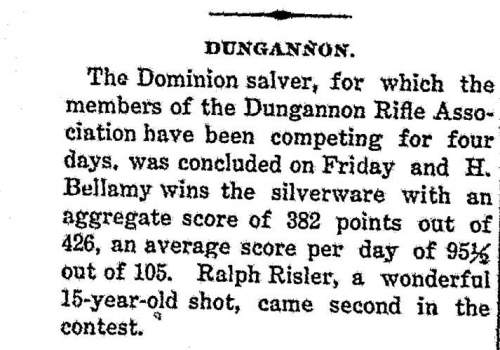

Assigned to the 58th Battalion in Europe, Pte. Bellamy appeared once again in the pages of the local weeklies through his letters from the front. Stationed “somewhere in France” on Dec. 26th, 1916, Harry wrote to his friend F. Ross of how his “three or four days’ trench life” had begun with digging out a trench collapsed by shell-fire; he had become accustomed to ducking down for enemy fire “no matter how deep the mud and water is.” While evading sniper bullets in a no man’s land crater, Bellamy says he pretended he was at home, practicing with friends at the Dungannon Rifle Association.

The Wingham Times, 1911-12-28, pg 4

Imagining away the conditions he described would have no doubt been difficult: “We sleep and rest in the dugouts, which are twenty to twenty-five feet underground. After splashing, crawling and wading through trench mud for hours at a time, we find it quite a relief to get down in these underground quarters.” On Christmas day he witnessed “a fierce bombardment…It was a magnificent sight to see the green and red flames and the shells with their tails of fire flying…The noise and din of the various kinds of explosives in use was deafening.” In the same letter, which Goderich’s The Signal printed on its front page, he claimed that the brutal lifestyle had not dampened the soldiers’ spirits: “we never worry over here. We content ourselves with singing, ‘Pack all your troubles in your old kit bag and smile, smile, smile.’”

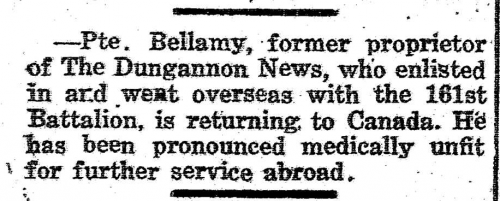

Although he was writing for the local papers, Pte. Bellamy was not able to regularly read them in Europe, and complained that the delays in mail also prevented him from keeping up-to-date with happenings in Huron County. According to his service records, a year after he had enlisted at Goderich, Harry fell ill with trench fever–an infectious disease carried by body lice. He left France for treatment in the U.K., and after complaining of pain in his limbs at York County Hospital, doctors at the King’s Red Cross Canadian Convalescent diagnosed him with myalgia (joint pain) and an abnormally fast pulse.

The Huron Expositor, 1917-10-12, pg 5

In articles subsequently written for the Goderich Star, Pte. Bellamy did not detail his failing health, instead returning to his pen to share his experiences sightseeing on leave in Scotland and Ireland in August, 1917. Ever a committed imperialist, he enjoyed witnessing the Glorious Twelfth celebrations in Belfast, but reported caring less for his time in southern Ireland, since “there is no love lost between those in khaki and the Irish rebels.” He felt wistfulness upon the end of his holiday, but Pte. Bellamy’s belief in the righteousness of the war had not wavered; he used his Star articles to rally homefront sentiments against peace until the enemy could be decisively defeated: “let…every one of us, as Canadians, recapture the heroic mood in which we entered the war.”

The Signal, 1917-12-06, pg 6

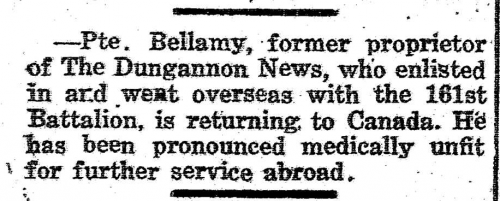

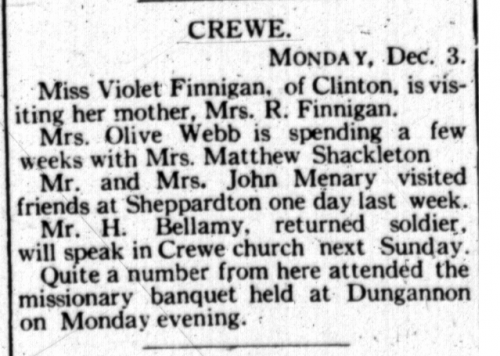

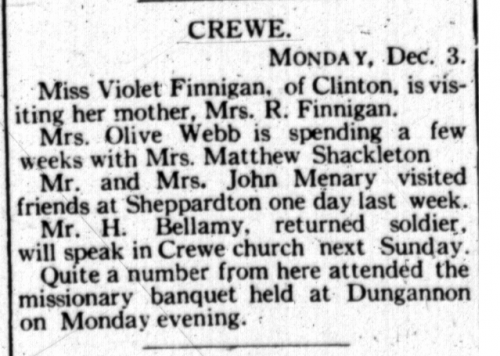

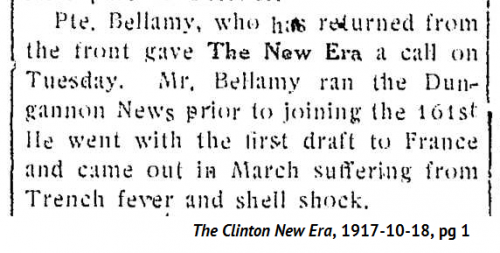

Unable to resume his duties as a soldier, Pte. Bellamy returned to Canada, where in addition to his persistent trench fever, he received a diagnosis of neurasthenia–a contemporary term broadly used for nervous disorders. After his homecoming, he reappeared frequently in the local news columns, usually receiving mention for promoting the war effort at local patriotic events or canvassing for Victory Loans.

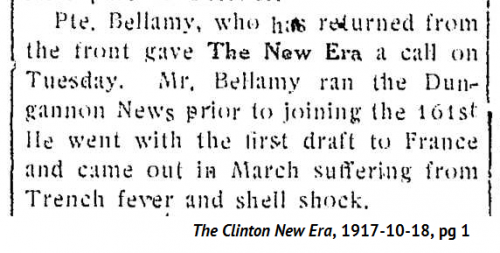

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

In April 1918, a medical board at Guelph honourably discharged Harry as medically unfit due to illness contracted on active service. His records list a ‘nervous debility,’ as well as trench fever as the causes for his dismissal, and note that “this man would not be able to do more than one quarter of a days [sic] work.” The listed symptoms in his medical records include dizzy spells, light headedness, restlessness, hand tremors, headaches, and an irregular heartbeat. The Board determined that the probable duration of his debility was “impossible to state.”

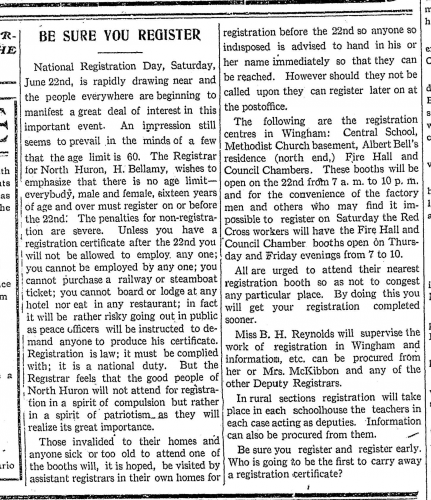

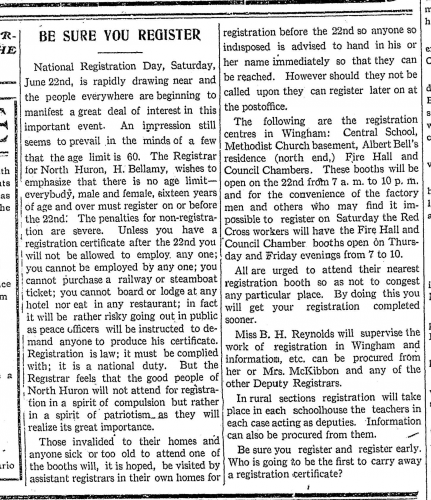

The Wingham Advance, 1918-06-13, pg 5

Despite experts’ doubts about his ability to cope with a full-time job, Harry received a temporary government position as North Huron’s Registrar for 1918’s National Registration Day effort. The federal government intended this wartime “man and woman power census” to identify available labour forces for the homefront and overseas by requiring all Canadians over sixteen to register.

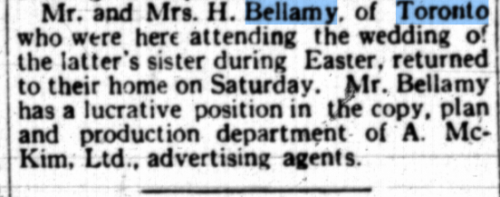

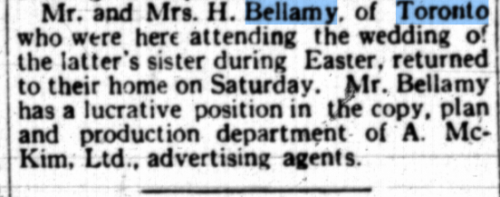

Nothing in the newspapers suggests that Harry Bellamy returned to printing or publishing on a full-time basis in Dungannon. After the war was over in 1919, Ashfield accepted Harry’s application for the township’s annual printing contract with special consideration to him as a “returned soldier,” but according to an item in The Wingham Advance he later declined the work for the pay offered. There was evidently a vocation that Harry Bellamy now felt more passionately for than journalism, because in May of that year the New Era records that he moved to Toronto to accept a bureaucratic position “in connection with the re-establishment of soldiers.” In 1921, Harry ultimately sold The Dungannon News printing equipment to a buyer from Meaford, and he and wife Annie settled permanently in Toronto.They didn’t entirely disappear from print, however, as local news columns over the next decade continued to note the couple’s visits to friends and family in Huron County.

The Signal, 1921-3-31, pg 4

Following Pte. Bellamy’s story via short items in the county papers certainly does not provide a full picture of his life, nor the toll of his experiences in the trenches of France. The information gleaned, though, does speak to the value of these local weeklies as historical resources, and that comparing them against other records–in this case Pte. Bellamy’s military personnel files– can help us to read between the lines. It’s also a pertinent reminder that both historical and news sources are better understood if we know a little about the context and perspective of the people creating them. What emerged in this case was the story of a man whose politics on the page never changed, whose service to the Canadian government continued beyond the battlefield and loyalty to the British empire never faltered, but who nevertheless could not quite pack the personal consequences of war away in an “old kit bag and smile, smile, smile.”

Hot off the Press: Seen in the County Papers opens Nov. 21st at the Huron County Museum! Visit the exhibit to learn more about the stories behind Huron’s historic headlines. You can browse the newspaper collection from the comfort of home at dev.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers. Information for this blog post came from Huron County’s digitized newspapers and Library and Archives Canada’s digitized service records.

by Sinead Cox | May 2, 2017 | Artefacts, Collection highlights, Exhibits, Project progress, Uncategorized

Guest blogger and local Wingham artist Becca Marshall finishes her series on the museum as ‘gathering place’ with a behind the scenes look at her exhibit on display now at Brock University.

After a long year of photographing, developing, printing, and researching, we have finally made it to the finish line. As such, the end of my project was marked with a gallery exhibition of the photographs I took throughout the year accompanied by text and installation pieces on April 13th at the Marilynn I. Walker School of Fine and Performing Arts in St. Catharines, ON. I thought I would include some photos and descriptions of the pieces below for those who wish to see the end result, or, if you are in the area you can go to the gallery and see the installation in person (On display Tuesday-Saturday from 1-5 pm until May 5th).

A couple of photos from the installation process.

Over the course of a couple of days and with the assistance of Matthew Tegal and Marcie Bronson from Rodman Hall, and Professor Amy Friend and Lesley Bell from Brock University, we were able to set up and install the show.

Step Lightly (2017) Pigment print on luster paper and graphite This is the beginning piece of the exhibition. The photo features the train of Jean (Scott) Taylor’s wedding dress and is accompanied by personal writing in graphite directly on the wall next to the image so that it can only be seen up close. A smaller image is hidden to the side of the text of an old bottle of Potassium Chlorate medication.

Shelf Life (2017) Assortment of boxes This piece takes up the span of the long wall. The eclectic boxes are a stand in for the discovery process that a person experiences in the museum. Visitors are encouraged to take their time opening the boxes and looking for things that might have been left behind.

Pulling Threads (2017) Pigment print on luster paper, graphite, and archival tissue paper This piece consists of the large format print of the child’s sewing machine from the museum coupled with a collage of tissue paper with fragmented writing. Beneath these sheets are more hidden photos. The viewer either has to lift the pages up to view the smaller pieces, or they might catch a glimpse when someone walks by and the breeze lifts up the pages for a few moments, exposing the photos underneath.

Twelve Parts Fragile (2017) Pigment print on cotton rag paper The final piece of the show is a series of artifact photographs presented side by side so that they read like a sentence. This piece ties together the nature of the museum- the bringing together of like and unlike things to share their stories.

In many ways, I still cannot believe that this project is over. It was the experience of a lifetime and I am so grateful to the incredible staff at the museum who so generously gave their time and resources to help me better understand the nature of collections, curation, and our relationship to artifact display.

In many ways, I still cannot believe that this project is over. It was the experience of a lifetime and I am so grateful to the incredible staff at the museum who so generously gave their time and resources to help me better understand the nature of collections, curation, and our relationship to artifact display.

Additionally, without the support of my supervising instructors, Professor Amy

Friend and Dr. Keri Cronin, along with the advice and aid of Matthew Tegal, Marcie Bronson, and Lesley Bell, this project would never have gotten off the ground. Their constant support was of the utmost value. Overall, I learned so much about the silent conversations and nuances that inform our interactions with artifacts from the past – and I am so grateful for those of you who followed

me along on this journey.

by Sinead Cox | May 9, 2016 | Exhibits, Investigating Huron County History

Not every new neighbor throughout Huron County’s history has been welcomed universally by the community; some have faced prejudice and discrimination. Education and Programming Assistant Sinead Cox, who led research for the current Stories of Immigration and Migration Exhibit, writes about the hostility and misconceptions faced by one of these migrant groups.

In 1895, an anonymous East Wawanosh farmer called for an end to the immigration of a despised immigrant group to Canada. Suspected of being untrustworthy and even violent, the farmer lamented to the Daily Mail & Empire that these migrants were “a curse to the country, as a rule.” The dangerous group he was referring to were young, poor, British children.

Article from the Daily Mail and Empire, July 23, 1895.

Between the 1860s and 1930s, U.K. charity homes sent thousands of urban boys and girls commonly known as ‘home children’ to Australia, South Africa and Canada as farm labourers or domestic servants. These young migrants feared as a threat to the moral character of Canadian society had little say in leaving the country of their birth, or their estrangement from any family they might have still had there. In 2010 the U.K. government officially apologized for the forced emigration of these children, which often involved what charity home founder Dr. Thomas Barnardo termed ‘philanthropic abduction’: sending poor children across the ocean without the knowledge of their still-living parents, siblings or guardians. Without knowing the children might be sent half a world away, caretakers had often placed them in the homes because of a sudden lack of funds to properly care for them, sometimes due to unemployment, insufficient wages, or the death or illness of a parent.

Between the 1860s and 1930s, U.K. charity homes sent thousands of urban boys and girls commonly known as ‘home children’ to Australia, South Africa and Canada as farm labourers or domestic servants. These young migrants feared as a threat to the moral character of Canadian society had little say in leaving the country of their birth, or their estrangement from any family they might have still had there. In 2010 the U.K. government officially apologized for the forced emigration of these children, which often involved what charity home founder Dr. Thomas Barnardo termed ‘philanthropic abduction’: sending poor children across the ocean without the knowledge of their still-living parents, siblings or guardians. Without knowing the children might be sent half a world away, caretakers had often placed them in the homes because of a sudden lack of funds to properly care for them, sometimes due to unemployment, insufficient wages, or the death or illness of a parent.

Child Migration was intended to ease urban poverty in the British Isles and agricultural labour shortages in the colonies.Once in Canada, the children were expected to work and attend school, and received infrequent inspection visits to monitor their welfare. Canadian employers tended to treat the young immigrants as hired hands, rather than adopted family members, and many changed homes frequently. Although rural Canada might have provided more employment opportunities than urban England, living among strangers often left the children vulnerable to abuse, neglect or overwork with tragic results. In 1923, Huron County farmer John Benson Cox was convicted of abusing Charles Bulpitt, the sixteen-year-old ‘home boy’ working for him, after Charles died by suicide in his care.

Excerpt from The Montreal Gazette, Feb. 8, 1924

At the time, some Canadians welcomed the cheap farm labour provided by the child migrants, while others feared that these lower class ‘waifs and strays’ must be ‘the offspring of criminals and tramps,’ and therefore inherently bad and dangerous to God-fearing citizens of the Dominion. In Canadian author L.M. Montgomery’s beloved classic, Anne of Green Gables, character Marilla Cuthbert famously dismissed the possibility of welcoming a child from the U.K. charity homes to Green Gables:

At first Matthew suggested getting a Barnardo boy. But I said ‘no’ flat to that. They may be all right—I’m not saying they’re not—but no London Street Arabs for me…I’ll feel easier in my mind and sleep sounder at nights if we get a born Canadian.

Public fears about these ‘street Arabs’ were no doubt influenced by the widespread popularity of the pseudoscientific practice of eugenics at the turn of the twentieth century. Eugenicists erroneously believed that some people were genetically superior to others, and these good traits would be diluted and society damaged by mixing with groups having supposedly inferior genes, including the mentally ill or developmentally challenged. Eugenicist policies were widely touted by many prominent Canadians, including philanthropists and legislators.

At an 1894 federal Select Standing Committee on Agriculture and Colonisation, East Huron Member of Parliament Dr. Peter Macdonald spoke against government subsidies for the immigration of ‘home children.’ His concerns were not based on the welfare and safety of the young immigrants, but on the potential ill effect their introduction would have on Canadian society, particularly because of their eventual intermarriage with existing Canadian settler families:

August 13, 1906 Globe and Mail article describing the arrival of 200 Barnardo Home boys, which included Bernard Brown.

Those children are dumped on Canadian soil, who, in my opinion, should not be allowed to come here at all. It is just the same as if garbage were thrown into your backyard and allowed to remain there. We find from the testimony of disinterested parties in this country, that a large number of these children have turned out bad, and are poisoning our population by intermarrying with them…I think myself this committee should unite in an expression of opinion that no such $2 a head should be paid by this government to bring such a refuse of the old country civilization, and pour it in here among our people. We take more means to purify our cattle than to purify our population?

Despite objectors like Macdonald, charity homes sent more than 100,000 British children to Canada, and today likely millions of Canadians are the descendants of these children who, despite the hardships of forced migration and separation from loved ones in childhood, often survived and persevered to earn a living and raise a family of their own. Although they had essentially been exiled by the British Empire, a huge proportion of ‘home boys’ also later volunteered to serve in the first and second world wars as young men.

Bernard Brown in his military uniform. He enlisted with the 161st Regiment of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces in January 1916. Photo courtesy of Brown Family.

One such child migrant, Bernard Brown (1896-1918), came to Huron County at ten years old. Bernard’s journey from a poor, struggling family in Northern Ireland that could not afford to feed all of their children, to an English charity home, to a Tuckersmith Township farm, and finally to the battlefields of France, was featured in the Huron County Museum’s Stories of Immigration and Migration, a temporary exhibit that tracks the narratives of seven families who came to our county between 1840 and 2007.

Similarly to many refugee families today, child migrants like Bernard Brown did not choose Huron County as their ultimate destination, but were matched there. When Bernard was placed with a couple in Tuckersmith, he was separated from his younger brother Edward whom Barnardo’s sent to Ripley, Bruce County. In hindsight, cases of mistreatment and neglect indicate that these young people an ocean away from loved ones, unable to return home and at the mercy of strangers, ultimately had much more to fear from Canadians than Canadians had to fear from them. The eventual success and resilience of those who survived childhood and the millions among us who can today claim a ‘home child’ as an ancestor are a testament to the fact that although the U.K and Canadian governments may have tragically failed them, the ‘home children’ contributed immeasurably to our communities rather than ‘poisoned’ them.

To find out more about the experience of one home child in Huron County, see Bernard’s story when you visit Stories of Immigration and Migration, on display in the Temporary Gallery at the Huron County Museum until October 15th, 2016. Are you descended from a home child? Share your family’s story with us tagged #homeinhuron or add it to the visitor-submitted stories in the exhibit.

by Sinead Cox | Mar 9, 2016 | Exhibits, Investigating Huron County History, Project progress

What’s your journey to Huron County? This spring, visitors to the Huron County Museum can follow the journeys of seven families across the globe and through time in Stories of Immigration and Migration, a temporary exhibit dedicated to tales of settling in Huron County. The exhibit traces the circumstances that caused individuals within Canada and across the world to leave their former homes, as well as the migrants’ experiences building new lives in Huron. With Stories set to open on April 5th, researcher Sinead Cox shares why the journeys of some Huron County families are more difficult to research than others:

Museum staff are looking forward to shedding light on local histories that have never been featured in our galleries before with Stories of Immigration and Migration, an exhibit which spans a period from 1840 to the present day. When research started several months ago, I had the pleasure and privilege of speaking or corresponding directly with the more recent ‘migrants’ featured in the exhibit, and the opportunity to include their own words, insights and chosen artefacts. For those individuals who arrived more than a century ago, however, our research relied on archival records that often uncovered as many questions as answers.

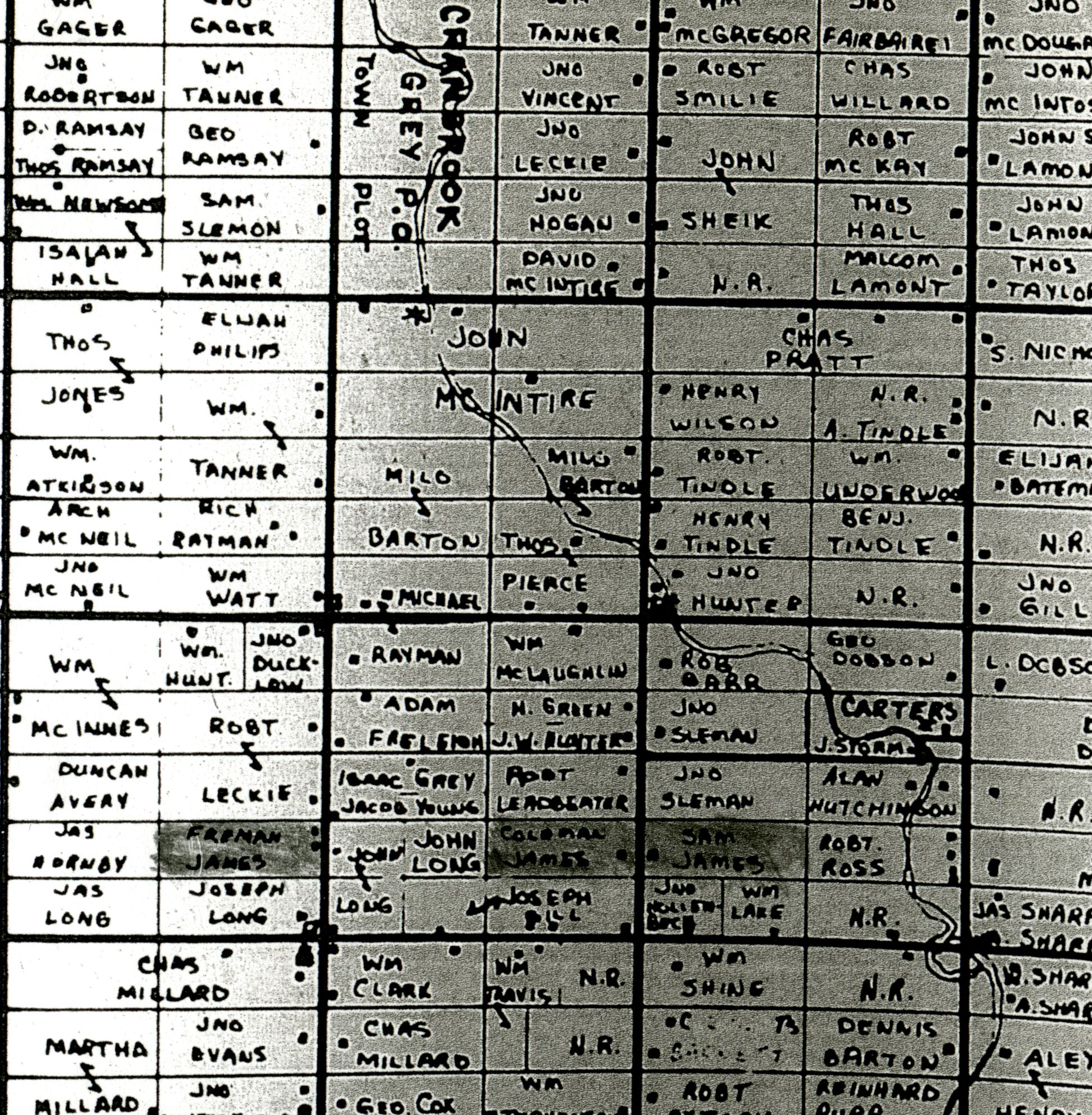

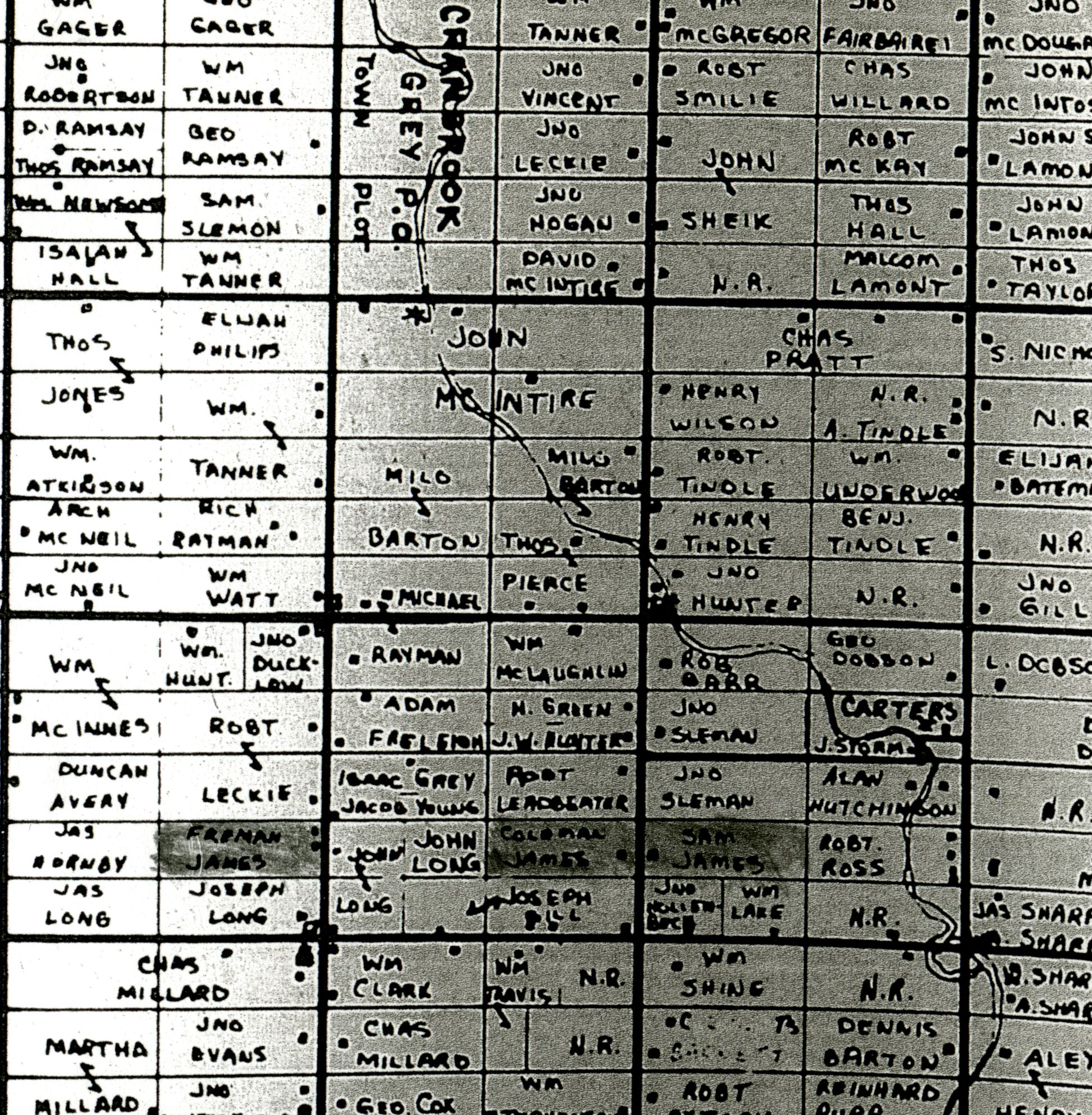

One compelling story that remains incomplete is that of Samuel and Mary Catherine James, a Black farming couple born in Nova Scotia who were some of the earliest settlers in Grey Township circa the 1850s. Nova Scotia was a destination for many former slaves from the colonial United States, including loyalists who had served the British crown during the American Revolution, in the eighteenth century. The James family also lived in Peel, Wellington County, before settling in Grey–which was part of the “Queen’s Bush” territory, rather than the Huron Tract lands managed by the Canada Company. Since the Jameses were farmers, they probably came to Huron County to achieve the same objective as most other pioneers: to own land. The James clan, including children Freeman, Coleman, Magdalene and Colin, farmed in a row on Lots 24 of Concessions 9, 10 and 12, Grey Township. According to 1861 census records, the whole family lived together in the same log house when they first moved to Huron.

Tragedy struck the James family when, in a matter of only three months–between November 1866 and January 1867–Colin (aged 23), Freeman (aged 39), and Mary Catherine (aged 77) all died. Whether their passings were related or coincidental, this unimaginable loss must have been a devastating blow to a pioneer family that relied on family members to share the burden of work. Mother and sons are buried at Knox Presbyterian Cemetery, Cranbrook.

According to land registry records, Freeman’s farm at Lot 24, Concession 12, still not purchased from the crown at the time of his death, was taken over by his sister Magdalene “Laney” James’ husband, Charles Done. Charles was also a Black farmer from Nova Scotia, and living in Howick when he married Laney at Ainleyville (now Brussels) on November 4th, 1867.

Laney and Coleman, the two surviving James siblings, each raised large families in Grey Township. In the 1871 census, Coleman and his wife, Lucy Scipio, already had eight children, five of them attending school. According to the same census, both Coleman and Laney could read and write, but their spouses could not. The family was struck by tragedy once again in April, 1873 when Coleman’s nine-year-old son, also named Coleman, died of “inflammation of [the] liver” after an illness of nine months.

Coleman sold his farms in 1875, and by the 1881 Canadian census, both he and Laney had left Huron County and relocated to Raleigh, Kent County with their families. This move to Raleigh would have enabled the James siblings to join a larger Black community at Buxton: a settlement founded by refugees that came to Canada through the Underground Railway.

The James family had relocated many times: according to tombstone transcriptions, Mary Catherine was born in Shelburne, Nova Scotia, and Colin in Digby, before the family moved to Ontario and lived in Wellington County, Huron County, and Kent. Census, birth and death records indicate that Coleman’s children ultimately settled in Michigan. Most farm families in nineteenth-century Ontario moved in search of the same benefits: a supportive community life, the ability to make a living, and good agricultural land. Black farmers, however, faced barriers of discrimination and exclusion that white settlers did not, and this sometimes necessitated leaving years of hard work behind to repeatedly seek a better life elsewhere.

It’s that moving on that can make traces of Huron County’s early Black settlers difficult to find in history books or public commemorations. The collections at the Huron County Museum, for example, are entirely acquired through donations from the community, which tends to emphasize the experiences of families that stayed here, found success, and had descendants who retain ties to the county to this day. We know less about the settlers who moved out of the county-even those who lived in Huron for decades, like the Jameses– and thus we also lack clarity about the opportunities they sought elsewhere, or the specific challenges they may have faced here.

The details I could glean from a few days’ of research did not provide enough information to interpret why the James family came to Huron County–or why they left–for Migration Stories. But I hope future research opportunities will add to this initial knowledge, and to a better understanding of the contributions and experiences of the individuals who have moved in and out of Huron County, including Black pioneers like the James family.

Special thanks to Reg Thompson, research librarian at the Huron County Library, for starting and contributing to the research used for this piece. If you have information about the James family and would like to share, contact Sinead, exhibit researcher: sicox@huroncounty.ca

You can see Stories of Immigration and Migration at the Huron County Museum (110 North Street) from April 5th until October 15th, 2016.

This post was originally published in February and republished in March after technical difficulties with the server.

Meagan Barnhart is a Mississauga Ojibwe (Anishinabe)/ Cayuga (Haudenosaunee) artist from McKerrow, Ontario and a Cultural Heritage Conservation and Management student at Fleming College. An exhibit featuring Meagan’s 7-piece bead embroidery series inspired by K-pop group BTS (as well as 10 smaller beaded flowers), is temporarily on display at the Huron County Museum.

Meagan Barnhart is a Mississauga Ojibwe (Anishinabe)/ Cayuga (Haudenosaunee) artist from McKerrow, Ontario and a Cultural Heritage Conservation and Management student at Fleming College. An exhibit featuring Meagan’s 7-piece bead embroidery series inspired by K-pop group BTS (as well as 10 smaller beaded flowers), is temporarily on display at the Huron County Museum. became a fan of BTS, and why they are such inspirations for your work?

became a fan of BTS, and why they are such inspirations for your work?

For the flowers, I often tried my best to try to use wildflowers of North America, specifically ones I’m most familiar with in Canada…I would research the meaning of the flowers or what their uses were – if I already knew what they represented or what they were used for, the better. I wanted to choose flowers that would tell a story – something that related to the music video, or BTS’s relationship with their fandom ARMY – especially since their bond is a lot stronger than I have ever seen between artist and fandom. From there I would develop a pattern. I often enjoyed the somewhat-symmetrical design; I say somewhat, because although it looks symmetrical, nothing is ever perfect, and neither are they, they don’t line up perfectly and they don’t have the same amount of beads on each side.

For the flowers, I often tried my best to try to use wildflowers of North America, specifically ones I’m most familiar with in Canada…I would research the meaning of the flowers or what their uses were – if I already knew what they represented or what they were used for, the better. I wanted to choose flowers that would tell a story – something that related to the music video, or BTS’s relationship with their fandom ARMY – especially since their bond is a lot stronger than I have ever seen between artist and fandom. From there I would develop a pattern. I often enjoyed the somewhat-symmetrical design; I say somewhat, because although it looks symmetrical, nothing is ever perfect, and neither are they, they don’t line up perfectly and they don’t have the same amount of beads on each side.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

In many ways, I still cannot believe that this project is over. It was the experience of a lifetime and I am so grateful to the incredible staff at the museum who so generously gave their time and resources to help me better understand the nature of collections, curation, and our relationship to artifact display.

In many ways, I still cannot believe that this project is over. It was the experience of a lifetime and I am so grateful to the incredible staff at the museum who so generously gave their time and resources to help me better understand the nature of collections, curation, and our relationship to artifact display.

Between the 1860s and 1930s, U.K. charity homes sent thousands of urban boys and girls commonly known as ‘home children’ to Australia, South Africa and Canada as farm labourers or domestic servants. These young migrants feared as a threat to the moral character of Canadian society had little say in leaving the country of their birth, or their estrangement from any family they might have still had there. In 2010 the U.K. government officially apologized for the forced emigration of these children, which often involved what charity home founder Dr. Thomas Barnardo termed ‘philanthropic abduction’: sending poor children across the ocean without the knowledge of their still-living parents, siblings or guardians. Without knowing the children might be sent half a world away, caretakers had often placed them in the homes because of a sudden lack of funds to properly care for them, sometimes due to unemployment, insufficient wages, or the death or illness of a parent.

Between the 1860s and 1930s, U.K. charity homes sent thousands of urban boys and girls commonly known as ‘home children’ to Australia, South Africa and Canada as farm labourers or domestic servants. These young migrants feared as a threat to the moral character of Canadian society had little say in leaving the country of their birth, or their estrangement from any family they might have still had there. In 2010 the U.K. government officially apologized for the forced emigration of these children, which often involved what charity home founder Dr. Thomas Barnardo termed ‘philanthropic abduction’: sending poor children across the ocean without the knowledge of their still-living parents, siblings or guardians. Without knowing the children might be sent half a world away, caretakers had often placed them in the homes because of a sudden lack of funds to properly care for them, sometimes due to unemployment, insufficient wages, or the death or illness of a parent.