by Sinead Cox | Jan 4, 2017 | Artefacts, Collection highlights, Investigating Huron County History, Project progress

Introducing a Brock University Student’s Project in Collaboration with the Huron County Museum & Archives, PART II

For those who missed the last post, my name is Becca Marshall – a fourth year student from Brock University where I am working on a school project with the assistance of the Huron County Museum and Archives. Basically, I am creating a series of analog photographs of museum artifacts along with a research paper as I study the theory of removed perception and constructed narratives in museums. If you want more background on my project, check out the original post that introduces my research! Today I want to update you on one of my favourite artifacts to research and photograph thus far – a linoleum block carved by Tom Pritchard.

At first I think I gravitated towards Pritchard’s linoleum blocks because my “art student” side was simply interested in seeing a piece of this artistic practice, as linoleum block printing is not something you encounter often nowadays. Not only does the museum have a collection of Pritchard’s linoleum blocks, but also a sketchbook and some of his art supplies. The most interesting part of this discovery process was going to find out more about Pritchard in the archives, only to discover that most of his folder was full of documents pertaining to his experience in the war. This incident prompted a line of inquiry in my research regarding human nature’s urge to essentially “fill in the blanks” in order to neatly label someone; many of us don’t like loose ends so we try to wrap our understandings of people into neat little boxes. For example, I had labelled Pritchard as solely an artist in my mind until I read his file – after that whenever I wrote research notes I found myself referring to him as a soldier. In fact, this label became so fixed in my head that when I was sorting through my photographs of

At first I think I gravitated towards Pritchard’s linoleum blocks because my “art student” side was simply interested in seeing a piece of this artistic practice, as linoleum block printing is not something you encounter often nowadays. Not only does the museum have a collection of Pritchard’s linoleum blocks, but also a sketchbook and some of his art supplies. The most interesting part of this discovery process was going to find out more about Pritchard in the archives, only to discover that most of his folder was full of documents pertaining to his experience in the war. This incident prompted a line of inquiry in my research regarding human nature’s urge to essentially “fill in the blanks” in order to neatly label someone; many of us don’t like loose ends so we try to wrap our understandings of people into neat little boxes. For example, I had labelled Pritchard as solely an artist in my mind until I read his file – after that whenever I wrote research notes I found myself referring to him as a soldier. In fact, this label became so fixed in my head that when I was sorting through my photographs of

artifacts and pairing them with their donors I mistakingly wrote Pritchard’s name next to a WWII gas mask instead of his linoleum block. As I reflected on this little mishap, I remember thinking of what a large role our minds play when looking at history – as we often take what we consider the most important aspects of someones life and define them by it.

The e xperience with Pritchard’s artifacts and archival file significantly directed my research as I have started looking at more museum studies articles and books on how curators negotiate incorporating narrative within exhibitions, and also the role that the public plays in their interpretations. I am finding it endlessly fascinating how key choices made by the curator can cue certain readings from the public, yet also how each visitor’s lived experience often redefines each interpretation. Luckily for me there is a significant amount of literature that touches on narrative theory in museums, as well as the opportunity to ask questions of the great staff at the Huron County Museum and Archives.

xperience with Pritchard’s artifacts and archival file significantly directed my research as I have started looking at more museum studies articles and books on how curators negotiate incorporating narrative within exhibitions, and also the role that the public plays in their interpretations. I am finding it endlessly fascinating how key choices made by the curator can cue certain readings from the public, yet also how each visitor’s lived experience often redefines each interpretation. Luckily for me there is a significant amount of literature that touches on narrative theory in museums, as well as the opportunity to ask questions of the great staff at the Huron County Museum and Archives.

I also thought I might take the time to answer a question I receive often in terms of the artistic component of this project – which is “Why analog photography?” To be honest its a question I ask myself repeatedly as well (usually after a long day in the darkroom when only one print turns out). I chose to work in an analog process for this project because I was hoping that my artistic practice would reflect my experience at the museum – essentially embodying the idea of “careful touch.” I’ve found that working and photographing the artifacts feels like a very reverent experience, so I want my artistic process to reflect this as I take the time to physically manipulate the photos in the darkroom. I also find that there are parallels between working with the artifacts and working with the prints in concerns to preservation and value. To me, an analog photograph has a certain amount of value due to the fact that there are normally limited prints (and even then each print might be a bit different from the last!) as well as a certain level of preciousness since each photograph takes such a long time to process and complete. Additionally, I have been getting to learn a bit more about preservation of artifacts from the Museum Technician, which has lead me to make connections to the steps taken to preserve an analog photograph – such as keeping it in the fixative chemical bath for the right length of time so that the light does not deteriorate the print, or the never ending quest to avoid dust. In this way, I find that the analog process simply connects my practice.

I also thought I might take the time to answer a question I receive often in terms of the artistic component of this project – which is “Why analog photography?” To be honest its a question I ask myself repeatedly as well (usually after a long day in the darkroom when only one print turns out). I chose to work in an analog process for this project because I was hoping that my artistic practice would reflect my experience at the museum – essentially embodying the idea of “careful touch.” I’ve found that working and photographing the artifacts feels like a very reverent experience, so I want my artistic process to reflect this as I take the time to physically manipulate the photos in the darkroom. I also find that there are parallels between working with the artifacts and working with the prints in concerns to preservation and value. To me, an analog photograph has a certain amount of value due to the fact that there are normally limited prints (and even then each print might be a bit different from the last!) as well as a certain level of preciousness since each photograph takes such a long time to process and complete. Additionally, I have been getting to learn a bit more about preservation of artifacts from the Museum Technician, which has lead me to make connections to the steps taken to preserve an analog photograph – such as keeping it in the fixative chemical bath for the right length of time so that the light does not deteriorate the print, or the never ending quest to avoid dust. In this way, I find that the analog process simply connects my practice.

Until next time,

– Becca Marshall

by Sinead Cox | Dec 7, 2016 | Artefacts, Collection highlights, Investigating Huron County History, Project progress

In this guest post, University student Becca Marshall examines how photography can reveal the Huron County Museum as a ‘gathering place’ for both people and things, and how the two intersect.

Hi everyone! My name is Becca Marshall and I am currently a fourth year student at Brock University where I study Concurrent Education with a focus in Visual Art and History. I have always been interested in cross disciplinary studies, so when the opportunity came to combine my love of history and art in the form of an independent study course – I took it! As I considered directions for my project I kept finding myself being pulled back to the Huron County Museum where I was a summer student in 2015. Luckily for me, the museum staff offered to assist me on my year-long project developing a research paper and analog photography portfolio on the topics of ‘removed perception’ and constructed narrative. So today I thought I would give you all a peek at what I have been up to so far.

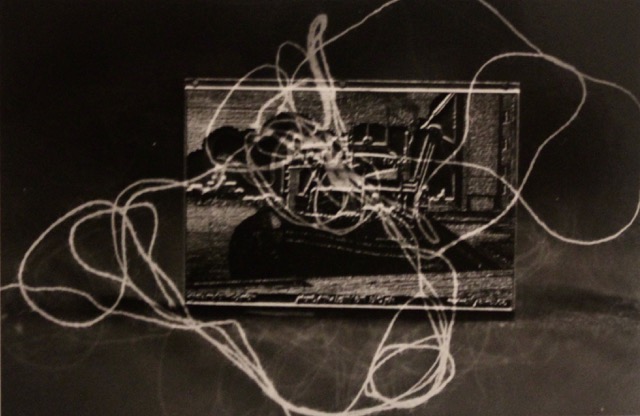

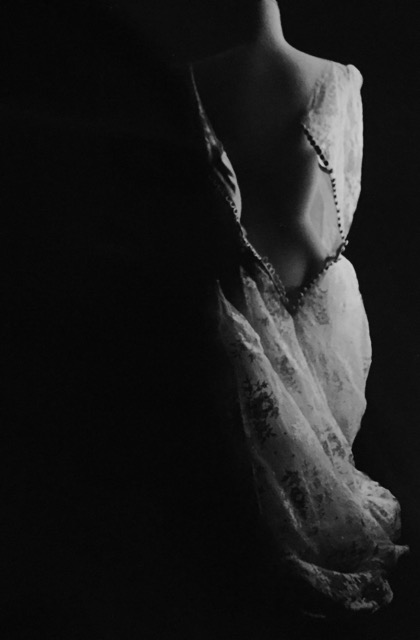

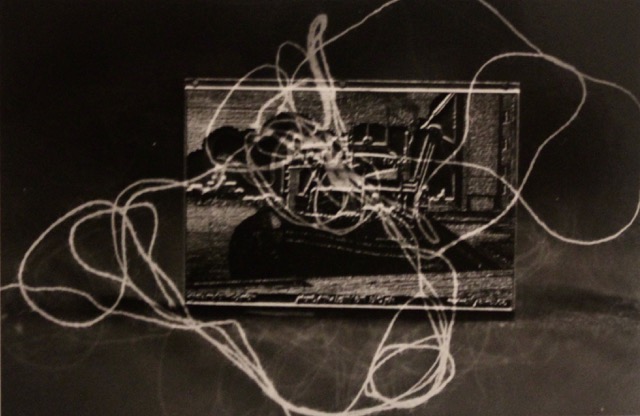

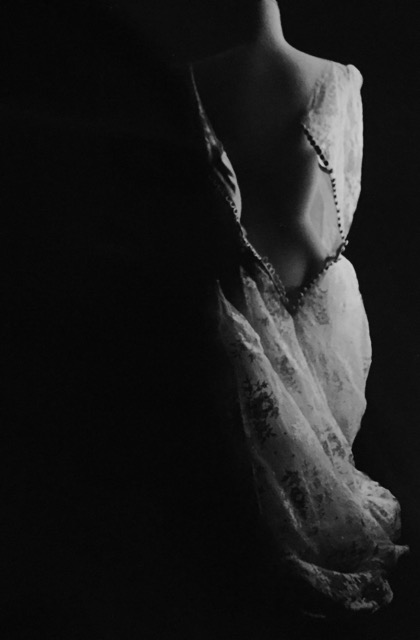

I started my project by photographing artifacts that are not currently on display in the museum’s main exhibition spaces. A large portion of my focus is looking at the museum as a “gathering place” (as one of my supervising professors termed it) and how even the most seemingly unconnected objects end up being tied together by the very fact that they all ended up in the same building. Some of my favourite artifacts to photograph so far have been a wedding dress belonging to Jean Taylor and a child’s sewing machine. Once I have the negatives developed I start working with methods of interrupting the images. Visual negations are a reference to our human tendency to insert ourselves into art and history and how this both enhances our experience, but also illuminates our limitations to understand an artifact’s experience objectively. These visual negations are indicative of my study of removed perception -how every single person will view an artifact (or a photo!) differently depending on their lived experiences. Essentially, the photos both highlight the personal relationships we form with artifacts while also recognizing a barrier – despite providing a window, a photo cannot physically transport someone back to the original objective context.

I started my project by photographing artifacts that are not currently on display in the museum’s main exhibition spaces. A large portion of my focus is looking at the museum as a “gathering place” (as one of my supervising professors termed it) and how even the most seemingly unconnected objects end up being tied together by the very fact that they all ended up in the same building. Some of my favourite artifacts to photograph so far have been a wedding dress belonging to Jean Taylor and a child’s sewing machine. Once I have the negatives developed I start working with methods of interrupting the images. Visual negations are a reference to our human tendency to insert ourselves into art and history and how this both enhances our experience, but also illuminates our limitations to understand an artifact’s experience objectively. These visual negations are indicative of my study of removed perception -how every single person will view an artifact (or a photo!) differently depending on their lived experiences. Essentially, the photos both highlight the personal relationships we form with artifacts while also recognizing a barrier – despite providing a window, a photo cannot physically transport someone back to the original objective context.

More specifically, in terms of technique I am working with an analog camera to create a series of silver-gelatin prints. Once I take the photos I remove the film in the darkroom, wind it onto a reel, put it in a canister, and then soak it in a series of chemical baths. After this process the film is developed and can be exposed to light as I remove it from the dark room and take it to the drying cabinet. After that I select the negative I want to make a print of and go into the darkroom with the red lights on (as red lights will not harm the light sensitive paper). Next, I insert my negative into an enlarger that will use directed light to expose the image onto my paper. It is during this process that I create any visual interruptions – for example the attached image of the sewing machine was created by dragging a thread across the paper for a split second during the exposure time. I then take the paper over to another series of chemical baths to develop the image. I am currently coming up with new ways to interrupt the images – for example I am experimenting with using a swath of lace during the exposure process on the wedding dress image to see what effect it produces. The entire process is incredibly engaging, and each artifact seems to demand a different sort of treatment that is entirely unique from the others.

More specifically, in terms of technique I am working with an analog camera to create a series of silver-gelatin prints. Once I take the photos I remove the film in the darkroom, wind it onto a reel, put it in a canister, and then soak it in a series of chemical baths. After this process the film is developed and can be exposed to light as I remove it from the dark room and take it to the drying cabinet. After that I select the negative I want to make a print of and go into the darkroom with the red lights on (as red lights will not harm the light sensitive paper). Next, I insert my negative into an enlarger that will use directed light to expose the image onto my paper. It is during this process that I create any visual interruptions – for example the attached image of the sewing machine was created by dragging a thread across the paper for a split second during the exposure time. I then take the paper over to another series of chemical baths to develop the image. I am currently coming up with new ways to interrupt the images – for example I am experimenting with using a swath of lace during the exposure process on the wedding dress image to see what effect it produces. The entire process is incredibly engaging, and each artifact seems to demand a different sort of treatment that is entirely unique from the others.

Dark room.

In terms of my research paper I am currently developing its direction through my experiences at the museum, studies in the archives, and by reading various books and journal articles. Through this process I hope to better understand the intentions, ethics, and reasoning behind how artifacts are displayed in museums. I want to learn how museums negotiate preserving the narratives of an artifact’s provenance, or how they may be used to illustrate larger messages, as well as how they reconcile artifacts with missing information (which arguably can be just as fascinating as an artifact that has pages recorded about its provenance). The inspiration for this research direction came from my encounter with a linoleum block in the collections room made by Thomas Pritchard. When I went to the archives to learn more about him I expected the file to be full of his artistic accomplishments – however much to my surprise, the majority of the documents were about his experience at war. I hope to write about this experience in greater detail in my next blog post as well as have a photo of his linoleum block developed at that time. By engaging in this research practice I hope to develop a better understanding about constructed and interpreted narrative through the display of artifacts in museums.

Overall, so far I am having an amazing experience getting to learn more about museums and engage with such uniquely wonderful artifacts. I cannot thank the staff at the Huron County Museum and Archives enough for assisting me with my studies and allowing me to see how art, history, and museum studies can all cross over and inform each other in the most interesting ways. I look forward to seeing how this project develops this year, and I hope you enjoy my periodic updates throughout the duration.

by Elizabeth French-Gibson | Nov 28, 2016 | Archives, Investigating Huron County History, Project progress

Late last autumn, the Huron County Museum was fortunate enough to receive funding from the Federal Government to produce, among other things, two films about Huron County during the First World War.

Maud Stirling was originally from Bayfield.

One film was about Huron County on the Home Front (watch here!) and the other was supposed to be about Maud Stirling, a nurse from Bayfield who was awarded the Royal Red Cross, 2nd Class. While doing background research for the films, I thought it would be interesting to see how many other women from Huron County enlisted as nursing sisters during the war, thinking I would only find a dozen or so more names. As of November 2016, 48 women with ties to Huron County have been identified as WWI nurses, with several other names on the “maybe” list. More research still needs to be done!

The list of names so far:

| Mary Agatha Bell

|

Ellie Elizabeth Love

|

| Mary Agnes Best

|

Marjorie Kelly

|

| Mary Ann Buchanan

|

Clara Evelyn Malloy

|

| Martha Verity Carling

|

Mary Mason

|

| Olive Maud Coad

|

Jean McGilvray

|

| Muriel Gwendoline Colborne

|

Beatrice McNair

|

| Lillian Mabel Cudmore

|

Mary Wilson Miller

|

| Alma Naomi Dancey

|

Anna Edith Forest Neelin

|

| Gertrude Donaldson (Petty)

|

Bertha Broadfoot Robb

|

| Mary Edna Dow

|

Barbara Argo Ross

|

| Lillian Beatrice Dowdell

|

Katherine Scott

|

| Elizabeth Dulmage

|

Ella Dora Sherritt

|

| Annie Isabel Elliott

|

Jeanette Simpson

|

| Frances M. Evans

|

Emmaline Smillie

|

| Annie Mae Ferguson

|

Annie Evelyn Spafford

|

| Clara Ferguson

|

Annie Maud Stirling

|

| Jean Molyneaux Ferguson

|

Helen Caton Strang

|

| Margaret Main Fortune

|

Vera Edith Sotheran

|

| Anna Ethel Gardiner

|

Mabel Tom

|

| Florence Graham

|

Cora Washington (married name Buchanan)

|

| Irene May Handford

|

Annie Whitely (Hennings)

|

| Bessie Maud Hanna

|

Ann Webster Wilson

|

| Ruth Johnson Hays

|

Harriet Edith Wilson

|

| Clara Hood

|

Jessie Wilson

|

Florence Graham was originally from Goderich, She was a nurse in the United States Army. She was killed in a car accident in France on May 27, 1919.

I learned that many women enlisted not just with the Canadian Army Medical Corps but also with the American or British Army. Here are just some of the resources I’ve used to help track down the nursing sisters and their stories:

Library and Archives Canada: for digitized personnel records, including Attestation Papers and service files

Great Canadian War Project: for an alphabetical list and nursing sister awards

The UK National Archives: for British Army nurses’ service records (caution – the records aren’t free)

Ancestry.ca: a number of different resources are useful on this site, including Imperial War Gratuities, 1919-1921 and New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917-1919. You need a subscription to access Ancestry or you can visit your local Huron County Library branch for free access!

Digitized Newspapers: Huron County’s newspaper have be one of the most useful resources for tracking down names of nursing sisters

There are many more women and stories to discover and I am looking forward to continuing on with this intriguing research project. Stay tuned for some of my discoveries!

by Sinead Cox | Mar 9, 2016 | Exhibits, Investigating Huron County History, Project progress

What’s your journey to Huron County? This spring, visitors to the Huron County Museum can follow the journeys of seven families across the globe and through time in Stories of Immigration and Migration, a temporary exhibit dedicated to tales of settling in Huron County. The exhibit traces the circumstances that caused individuals within Canada and across the world to leave their former homes, as well as the migrants’ experiences building new lives in Huron. With Stories set to open on April 5th, researcher Sinead Cox shares why the journeys of some Huron County families are more difficult to research than others:

Museum staff are looking forward to shedding light on local histories that have never been featured in our galleries before with Stories of Immigration and Migration, an exhibit which spans a period from 1840 to the present day. When research started several months ago, I had the pleasure and privilege of speaking or corresponding directly with the more recent ‘migrants’ featured in the exhibit, and the opportunity to include their own words, insights and chosen artefacts. For those individuals who arrived more than a century ago, however, our research relied on archival records that often uncovered as many questions as answers.

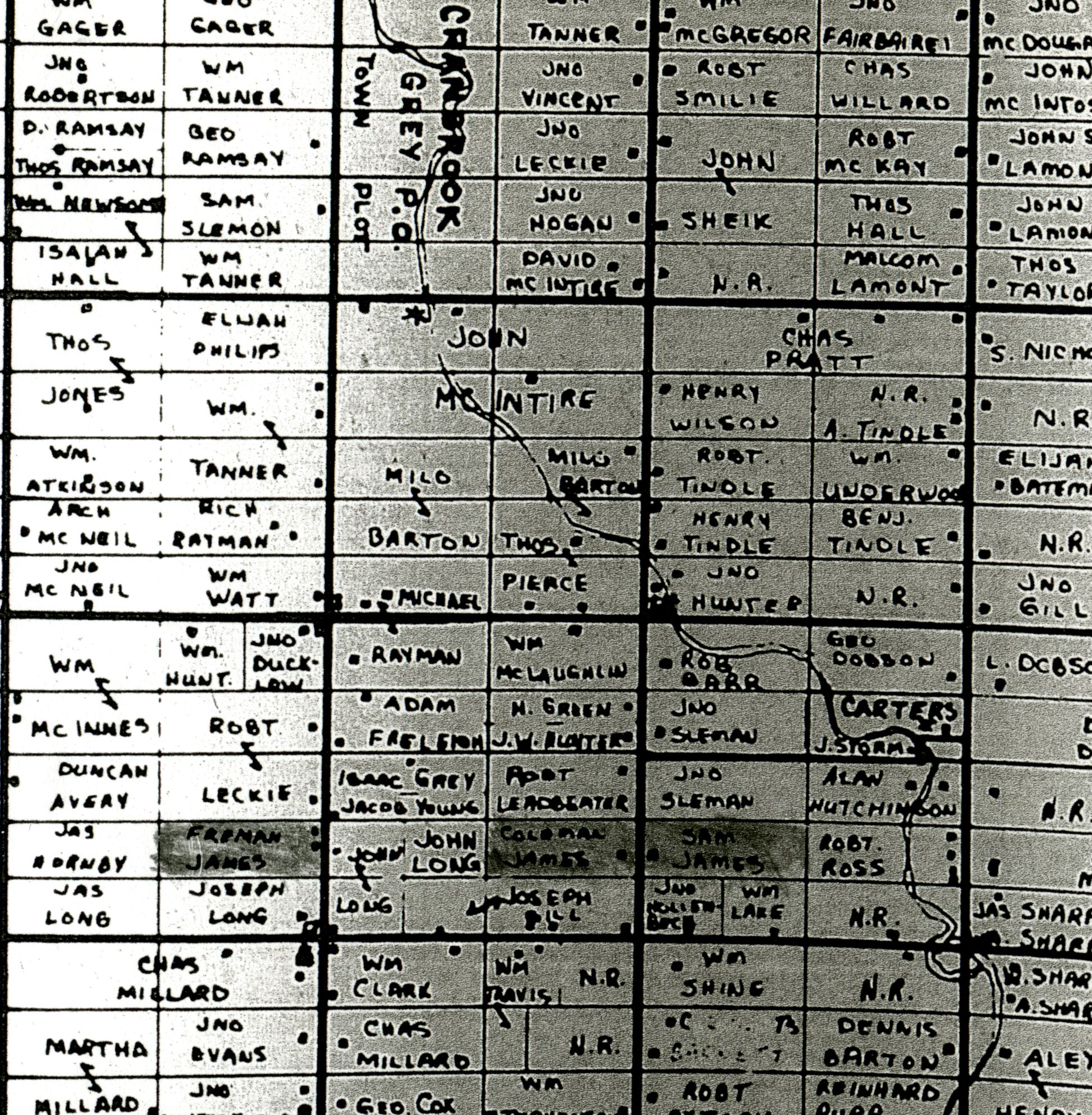

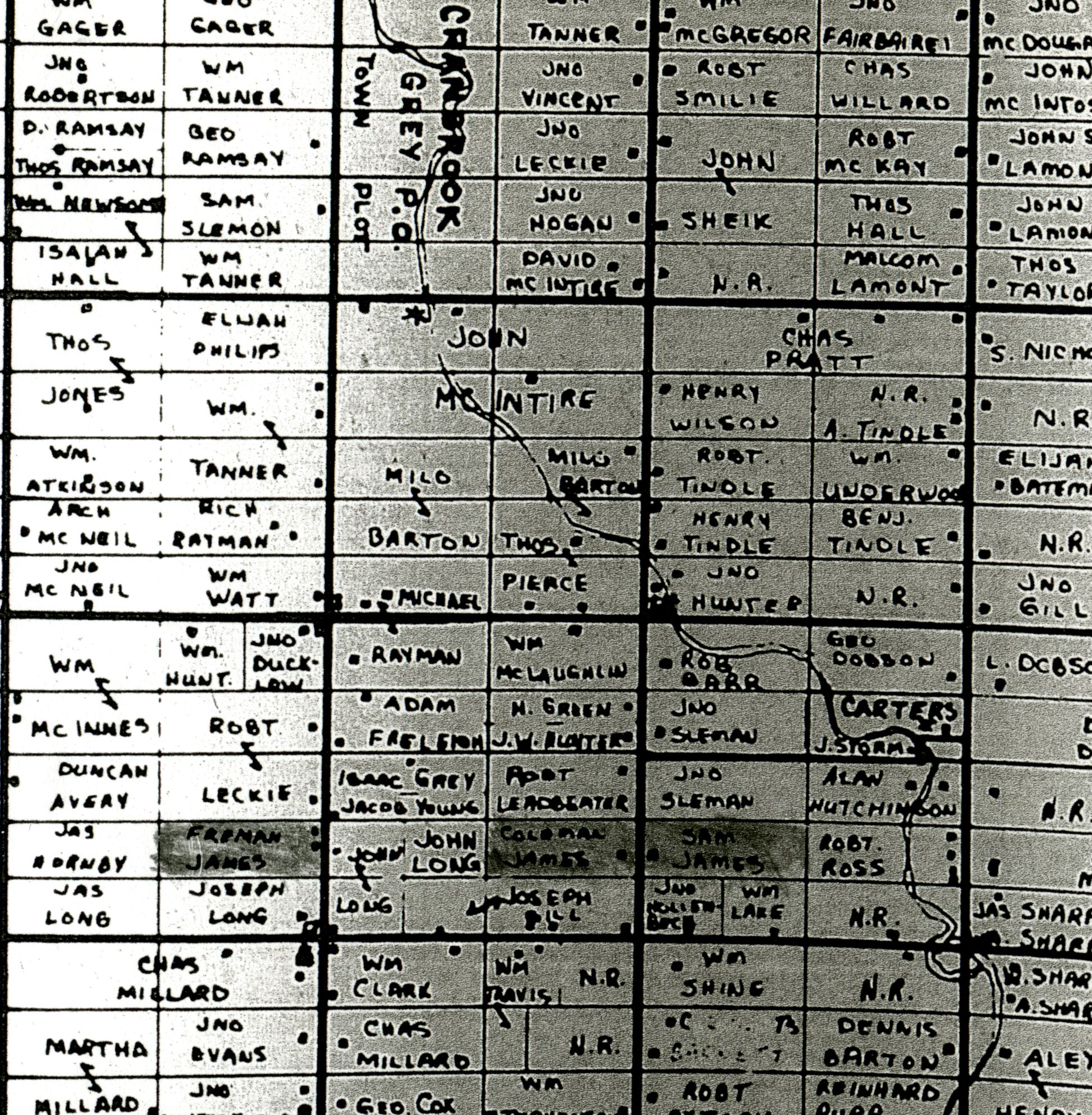

One compelling story that remains incomplete is that of Samuel and Mary Catherine James, a Black farming couple born in Nova Scotia who were some of the earliest settlers in Grey Township circa the 1850s. Nova Scotia was a destination for many former slaves from the colonial United States, including loyalists who had served the British crown during the American Revolution, in the eighteenth century. The James family also lived in Peel, Wellington County, before settling in Grey–which was part of the “Queen’s Bush” territory, rather than the Huron Tract lands managed by the Canada Company. Since the Jameses were farmers, they probably came to Huron County to achieve the same objective as most other pioneers: to own land. The James clan, including children Freeman, Coleman, Magdalene and Colin, farmed in a row on Lots 24 of Concessions 9, 10 and 12, Grey Township. According to 1861 census records, the whole family lived together in the same log house when they first moved to Huron.

Tragedy struck the James family when, in a matter of only three months–between November 1866 and January 1867–Colin (aged 23), Freeman (aged 39), and Mary Catherine (aged 77) all died. Whether their passings were related or coincidental, this unimaginable loss must have been a devastating blow to a pioneer family that relied on family members to share the burden of work. Mother and sons are buried at Knox Presbyterian Cemetery, Cranbrook.

According to land registry records, Freeman’s farm at Lot 24, Concession 12, still not purchased from the crown at the time of his death, was taken over by his sister Magdalene “Laney” James’ husband, Charles Done. Charles was also a Black farmer from Nova Scotia, and living in Howick when he married Laney at Ainleyville (now Brussels) on November 4th, 1867.

Laney and Coleman, the two surviving James siblings, each raised large families in Grey Township. In the 1871 census, Coleman and his wife, Lucy Scipio, already had eight children, five of them attending school. According to the same census, both Coleman and Laney could read and write, but their spouses could not. The family was struck by tragedy once again in April, 1873 when Coleman’s nine-year-old son, also named Coleman, died of “inflammation of [the] liver” after an illness of nine months.

Coleman sold his farms in 1875, and by the 1881 Canadian census, both he and Laney had left Huron County and relocated to Raleigh, Kent County with their families. This move to Raleigh would have enabled the James siblings to join a larger Black community at Buxton: a settlement founded by refugees that came to Canada through the Underground Railway.

The James family had relocated many times: according to tombstone transcriptions, Mary Catherine was born in Shelburne, Nova Scotia, and Colin in Digby, before the family moved to Ontario and lived in Wellington County, Huron County, and Kent. Census, birth and death records indicate that Coleman’s children ultimately settled in Michigan. Most farm families in nineteenth-century Ontario moved in search of the same benefits: a supportive community life, the ability to make a living, and good agricultural land. Black farmers, however, faced barriers of discrimination and exclusion that white settlers did not, and this sometimes necessitated leaving years of hard work behind to repeatedly seek a better life elsewhere.

It’s that moving on that can make traces of Huron County’s early Black settlers difficult to find in history books or public commemorations. The collections at the Huron County Museum, for example, are entirely acquired through donations from the community, which tends to emphasize the experiences of families that stayed here, found success, and had descendants who retain ties to the county to this day. We know less about the settlers who moved out of the county-even those who lived in Huron for decades, like the Jameses– and thus we also lack clarity about the opportunities they sought elsewhere, or the specific challenges they may have faced here.

The details I could glean from a few days’ of research did not provide enough information to interpret why the James family came to Huron County–or why they left–for Migration Stories. But I hope future research opportunities will add to this initial knowledge, and to a better understanding of the contributions and experiences of the individuals who have moved in and out of Huron County, including Black pioneers like the James family.

Special thanks to Reg Thompson, research librarian at the Huron County Library, for starting and contributing to the research used for this piece. If you have information about the James family and would like to share, contact Sinead, exhibit researcher: sicox@huroncounty.ca

You can see Stories of Immigration and Migration at the Huron County Museum (110 North Street) from April 5th until October 15th, 2016.

This post was originally published in February and republished in March after technical difficulties with the server.

by Sinead Cox | Aug 24, 2015 | Huron Historic Gaol, Project progress

The Huron Historic Gaol was an operational jail from 1841 until 1972. Many Huron County residents still remember the building when it housed inmates, as well as the governor or superintendent (jailer) and his family in the adjoining house; museum staff wanted to hear their stories to gather a more complete picture of day-to-day life living or working in jail. This summer, student museum assistant Mackenzie Bonnett met interview-partners with memories of the building prior to its 1972 closure at the gaol; he shares his first experiences with oral history.

Following the recent death of a former notable gaol employee, the Huron Historic Gaol and the archives at the Huron County Museum received a series of inquires into their life and time spent at the Gaol. Through these inquiries staff realised there is relatively little we know about the personal experiences of those that spent time at the Gaol while it was still in operation. We decided that the best way to learn more about these stories would be to get them directly from the source; this started my summer Gaol oral history project.

Following the recent death of a former notable gaol employee, the Huron Historic Gaol and the archives at the Huron County Museum received a series of inquires into their life and time spent at the Gaol. Through these inquiries staff realised there is relatively little we know about the personal experiences of those that spent time at the Gaol while it was still in operation. We decided that the best way to learn more about these stories would be to get them directly from the source; this started my summer Gaol oral history project.

I sought out people with any connection to the Gaol whether they were inmates, guards, maintenance staff, volunteers or family of the governor (jailer). A press release was sent out in early June to various local newspapers asking anyone with these types of connections to contact the gaol. Before starting any interviews I had to prepare myself with questions to organize and keep focus during the interview. I also had to prepare for the logistics of an oral history project which requires consent and release forms which allow people to assign a future date for when the information from their interview can be used.

Over the summer I conducted three interviews that each had their own interesting stories that told a variety of things about the Gaol and its staff and inmates that were not known to our staff today. I heard stories from friends and family of past Gaol Governors that heard firsthand accounts of day to day operations of the Gaol including escape attempts and notable prisoners. I also heard from Gaol volunteers that gave important insight into how the Gaol and its inmates were viewed by the community it served. I hope that the stories I heard and transcribed can be use in the future to aid with research and the creation of further exhibits.

by Elizabeth French-Gibson | Mar 14, 2014 | Project progress

By Emily Beliveau, Digital Projects Assistant

On March 13, 2014, we launched digital.huroncounty.ca, the end product of the Henderson Digitization Project.

The website displays over 850 newly digitized images taken by Goderich photographer J. Gordon Henderson and was produced with funding from the Ontario Government. This new website marks the beginning of a new era of digital participation for the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol. It is the first major digitization project undertaken by the Huron County Museum and the first time a collection has been made available to the public online.

The photographs on the website are an important part of local history that connects Huron County to world events. J. Gordon Henderson’s photographs not only tie Huron County into the Canadian experience of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, but the global experience of world war.

The project team is very excited to have this site alive and well and available for the world to start perusing. We launched the site in style with an evening event at the Huron County Museum that included live demos of the site, remarks from Lisa Thompson, MPP Huron Bruce and Warden Joe Steffler, a cash bar, refreshments, 1940s music, and a vintage-themed photo shoot. Pictures from the party are at the Museum’s Facebook page.

At first I think I gravitated towards Pritchard’s linoleum blocks because my “art student” side was simply interested in seeing a piece of this artistic practice, as linoleum block printing is not something you encounter often nowadays. Not only does the museum have a collection of Pritchard’s linoleum blocks, but also a sketchbook and some of his art supplies. The most interesting part of this discovery process was going to find out more about Pritchard in the archives, only to discover that most of his folder was full of documents pertaining to his experience in the war. This incident prompted a line of inquiry in my research regarding human nature’s urge to essentially “fill in the blanks” in order to neatly label someone; many of us don’t like loose ends so we try to wrap our understandings of people into neat little boxes. For example, I had labelled Pritchard as solely an artist in my mind until I read his file – after that whenever I wrote research notes I found myself referring to him as a soldier. In fact, this label became so fixed in my head that when I was sorting through my photographs of

At first I think I gravitated towards Pritchard’s linoleum blocks because my “art student” side was simply interested in seeing a piece of this artistic practice, as linoleum block printing is not something you encounter often nowadays. Not only does the museum have a collection of Pritchard’s linoleum blocks, but also a sketchbook and some of his art supplies. The most interesting part of this discovery process was going to find out more about Pritchard in the archives, only to discover that most of his folder was full of documents pertaining to his experience in the war. This incident prompted a line of inquiry in my research regarding human nature’s urge to essentially “fill in the blanks” in order to neatly label someone; many of us don’t like loose ends so we try to wrap our understandings of people into neat little boxes. For example, I had labelled Pritchard as solely an artist in my mind until I read his file – after that whenever I wrote research notes I found myself referring to him as a soldier. In fact, this label became so fixed in my head that when I was sorting through my photographs of xperience with Pritchard’s artifacts and archival file significantly directed my research as I have started looking at more museum studies articles and books on how curators negotiate incorporating narrative within exhibitions, and also the role that the public plays in their interpretations. I am finding it endlessly fascinating how key choices made by the curator can cue certain readings from the public, yet also how each visitor’s lived experience often redefines each interpretation. Luckily for me there is a significant amount of literature that touches on narrative theory in museums, as well as the opportunity to ask questions of the great staff at the Huron County Museum and Archives.

xperience with Pritchard’s artifacts and archival file significantly directed my research as I have started looking at more museum studies articles and books on how curators negotiate incorporating narrative within exhibitions, and also the role that the public plays in their interpretations. I am finding it endlessly fascinating how key choices made by the curator can cue certain readings from the public, yet also how each visitor’s lived experience often redefines each interpretation. Luckily for me there is a significant amount of literature that touches on narrative theory in museums, as well as the opportunity to ask questions of the great staff at the Huron County Museum and Archives. I also thought I might take the time to answer a question I receive often in terms of the artistic component of this project – which is “Why analog photography?” To be honest its a question I ask myself repeatedly as well (usually after a long day in the darkroom when only one print turns out). I chose to work in an analog process for this project because I was hoping that my artistic practice would reflect my experience at the museum – essentially embodying the idea of “careful touch.” I’ve found that working and photographing the artifacts feels like a very reverent experience, so I want my artistic process to reflect this as I take the time to physically manipulate the photos in the darkroom. I also find that there are parallels between working with the artifacts and working with the prints in concerns to preservation and value. To me, an analog photograph has a certain amount of value due to the fact that there are normally limited prints (and even then each print might be a bit different from the last!) as well as a certain level of preciousness since each photograph takes such a long time to process and complete. Additionally, I have been getting to learn a bit more about preservation of artifacts from the Museum Technician, which has lead me to make connections to the steps taken to preserve an analog photograph – such as keeping it in the fixative chemical bath for the right length of time so that the light does not deteriorate the print, or the never ending quest to avoid dust. In this way, I find that the analog process simply connects my practice.

I also thought I might take the time to answer a question I receive often in terms of the artistic component of this project – which is “Why analog photography?” To be honest its a question I ask myself repeatedly as well (usually after a long day in the darkroom when only one print turns out). I chose to work in an analog process for this project because I was hoping that my artistic practice would reflect my experience at the museum – essentially embodying the idea of “careful touch.” I’ve found that working and photographing the artifacts feels like a very reverent experience, so I want my artistic process to reflect this as I take the time to physically manipulate the photos in the darkroom. I also find that there are parallels between working with the artifacts and working with the prints in concerns to preservation and value. To me, an analog photograph has a certain amount of value due to the fact that there are normally limited prints (and even then each print might be a bit different from the last!) as well as a certain level of preciousness since each photograph takes such a long time to process and complete. Additionally, I have been getting to learn a bit more about preservation of artifacts from the Museum Technician, which has lead me to make connections to the steps taken to preserve an analog photograph – such as keeping it in the fixative chemical bath for the right length of time so that the light does not deteriorate the print, or the never ending quest to avoid dust. In this way, I find that the analog process simply connects my practice.

I started my project by photographing artifacts that are not currently on display in the museum’s main exhibition spaces. A large portion of my focus is looking at the museum as a “gathering place” (as one of my supervising professors termed it) and how even the most seemingly unconnected objects end up being tied together by the very fact that they all ended up in the same building. Some of my favourite artifacts to photograph so far have been a wedding dress belonging to Jean Taylor and a child’s sewing machine. Once I have the negatives developed I start working with methods of interrupting the images. Visual negations are a reference to our human tendency to insert ourselves into art and history and how this both enhances our experience, but also illuminates our limitations to understand an artifact’s experience objectively. These visual negations are indicative of my study of removed perception -how every single person will view an artifact (or a photo!) differently depending on their lived experiences. Essentially, the photos both highlight the personal relationships we form with artifacts while also recognizing a barrier – despite providing a window, a photo cannot physically transport someone back to the original objective context.

I started my project by photographing artifacts that are not currently on display in the museum’s main exhibition spaces. A large portion of my focus is looking at the museum as a “gathering place” (as one of my supervising professors termed it) and how even the most seemingly unconnected objects end up being tied together by the very fact that they all ended up in the same building. Some of my favourite artifacts to photograph so far have been a wedding dress belonging to Jean Taylor and a child’s sewing machine. Once I have the negatives developed I start working with methods of interrupting the images. Visual negations are a reference to our human tendency to insert ourselves into art and history and how this both enhances our experience, but also illuminates our limitations to understand an artifact’s experience objectively. These visual negations are indicative of my study of removed perception -how every single person will view an artifact (or a photo!) differently depending on their lived experiences. Essentially, the photos both highlight the personal relationships we form with artifacts while also recognizing a barrier – despite providing a window, a photo cannot physically transport someone back to the original objective context. More specifically, in terms of technique I am working with an analog camera to create a series of silver-gelatin prints. Once I take the photos I remove the film in the darkroom, wind it onto a reel, put it in a canister, and then soak it in a series of chemical baths. After this process the film is developed and can be exposed to light as I remove it from the dark room and take it to the drying cabinet. After that I select the negative I want to make a print of and go into the darkroom with the red lights on (as red lights will not harm the light sensitive paper). Next, I insert my negative into an enlarger that will use directed light to expose the image onto my paper. It is during this process that I create any visual interruptions – for example the attached image of the sewing machine was created by dragging a thread across the paper for a split second during the exposure time. I then take the paper over to another series of chemical baths to develop the image. I am currently coming up with new ways to interrupt the images – for example I am experimenting with using a swath of lace during the exposure process on the wedding dress image to see what effect it produces. The entire process is incredibly engaging, and each artifact seems to demand a different sort of treatment that is entirely unique from the others.

More specifically, in terms of technique I am working with an analog camera to create a series of silver-gelatin prints. Once I take the photos I remove the film in the darkroom, wind it onto a reel, put it in a canister, and then soak it in a series of chemical baths. After this process the film is developed and can be exposed to light as I remove it from the dark room and take it to the drying cabinet. After that I select the negative I want to make a print of and go into the darkroom with the red lights on (as red lights will not harm the light sensitive paper). Next, I insert my negative into an enlarger that will use directed light to expose the image onto my paper. It is during this process that I create any visual interruptions – for example the attached image of the sewing machine was created by dragging a thread across the paper for a split second during the exposure time. I then take the paper over to another series of chemical baths to develop the image. I am currently coming up with new ways to interrupt the images – for example I am experimenting with using a swath of lace during the exposure process on the wedding dress image to see what effect it produces. The entire process is incredibly engaging, and each artifact seems to demand a different sort of treatment that is entirely unique from the others.