Introducing a Brock University Student’s Project in Collaboration with the Huron County Museum & Archives, PART II

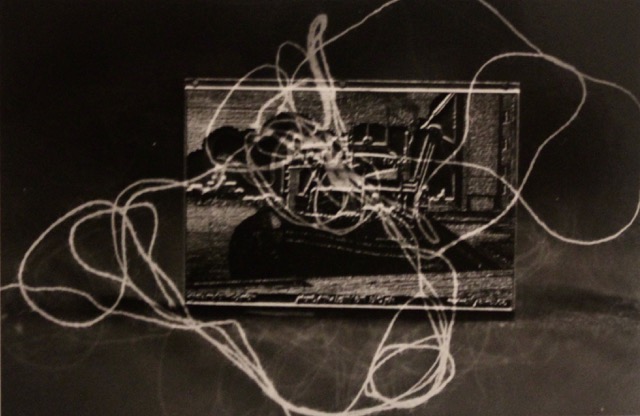

For those who missed the last post, my name is Becca Marshall – a fourth year student from Brock University where I am working on a school project with the assistance of the Huron County Museum and Archives. Basically, I am creating a series of analog photographs of museum artifacts along with a research paper as I study the theory of removed perception and constructed narratives in museums. If you want more background on my project, check out the original post that introduces my research! Today I want to update you on one of my favourite artifacts to research and photograph thus far – a linoleum block carved by Tom Pritchard.

At first I think I gravitated towards Pritchard’s linoleum blocks because my “art student” side was simply interested in seeing a piece of this artistic practice, as linoleum block printing is not something you encounter often nowadays. Not only does the museum have a collection of Pritchard’s linoleum blocks, but also a sketchbook and some of his art supplies. The most interesting part of this discovery process was going to find out more about Pritchard in the archives, only to discover that most of his folder was full of documents pertaining to his experience in the war. This incident prompted a line of inquiry in my research regarding human nature’s urge to essentially “fill in the blanks” in order to neatly label someone; many of us don’t like loose ends so we try to wrap our understandings of people into neat little boxes. For example, I had labelled Pritchard as solely an artist in my mind until I read his file – after that whenever I wrote research notes I found myself referring to him as a soldier. In fact, this label became so fixed in my head that when I was sorting through my photographs of

At first I think I gravitated towards Pritchard’s linoleum blocks because my “art student” side was simply interested in seeing a piece of this artistic practice, as linoleum block printing is not something you encounter often nowadays. Not only does the museum have a collection of Pritchard’s linoleum blocks, but also a sketchbook and some of his art supplies. The most interesting part of this discovery process was going to find out more about Pritchard in the archives, only to discover that most of his folder was full of documents pertaining to his experience in the war. This incident prompted a line of inquiry in my research regarding human nature’s urge to essentially “fill in the blanks” in order to neatly label someone; many of us don’t like loose ends so we try to wrap our understandings of people into neat little boxes. For example, I had labelled Pritchard as solely an artist in my mind until I read his file – after that whenever I wrote research notes I found myself referring to him as a soldier. In fact, this label became so fixed in my head that when I was sorting through my photographs of

artifacts and pairing them with their donors I mistakingly wrote Pritchard’s name next to a WWII gas mask instead of his linoleum block. As I reflected on this little mishap, I remember thinking of what a large role our minds play when looking at history – as we often take what we consider the most important aspects of someones life and define them by it.

The e xperience with Pritchard’s artifacts and archival file significantly directed my research as I have started looking at more museum studies articles and books on how curators negotiate incorporating narrative within exhibitions, and also the role that the public plays in their interpretations. I am finding it endlessly fascinating how key choices made by the curator can cue certain readings from the public, yet also how each visitor’s lived experience often redefines each interpretation. Luckily for me there is a significant amount of literature that touches on narrative theory in museums, as well as the opportunity to ask questions of the great staff at the Huron County Museum and Archives.

xperience with Pritchard’s artifacts and archival file significantly directed my research as I have started looking at more museum studies articles and books on how curators negotiate incorporating narrative within exhibitions, and also the role that the public plays in their interpretations. I am finding it endlessly fascinating how key choices made by the curator can cue certain readings from the public, yet also how each visitor’s lived experience often redefines each interpretation. Luckily for me there is a significant amount of literature that touches on narrative theory in museums, as well as the opportunity to ask questions of the great staff at the Huron County Museum and Archives.

I also thought I might take the time to answer a question I receive often in terms of the artistic component of this project – which is “Why analog photography?” To be honest its a question I ask myself repeatedly as well (usually after a long day in the darkroom when only one print turns out). I chose to work in an analog process for this project because I was hoping that my artistic practice would reflect my experience at the museum – essentially embodying the idea of “careful touch.” I’ve found that working and photographing the artifacts feels like a very reverent experience, so I want my artistic process to reflect this as I take the time to physically manipulate the photos in the darkroom. I also find that there are parallels between working with the artifacts and working with the prints in concerns to preservation and value. To me, an analog photograph has a certain amount of value due to the fact that there are normally limited prints (and even then each print might be a bit different from the last!) as well as a certain level of preciousness since each photograph takes such a long time to process and complete. Additionally, I have been getting to learn a bit more about preservation of artifacts from the Museum Technician, which has lead me to make connections to the steps taken to preserve an analog photograph – such as keeping it in the fixative chemical bath for the right length of time so that the light does not deteriorate the print, or the never ending quest to avoid dust. In this way, I find that the analog process simply connects my practice.

I also thought I might take the time to answer a question I receive often in terms of the artistic component of this project – which is “Why analog photography?” To be honest its a question I ask myself repeatedly as well (usually after a long day in the darkroom when only one print turns out). I chose to work in an analog process for this project because I was hoping that my artistic practice would reflect my experience at the museum – essentially embodying the idea of “careful touch.” I’ve found that working and photographing the artifacts feels like a very reverent experience, so I want my artistic process to reflect this as I take the time to physically manipulate the photos in the darkroom. I also find that there are parallels between working with the artifacts and working with the prints in concerns to preservation and value. To me, an analog photograph has a certain amount of value due to the fact that there are normally limited prints (and even then each print might be a bit different from the last!) as well as a certain level of preciousness since each photograph takes such a long time to process and complete. Additionally, I have been getting to learn a bit more about preservation of artifacts from the Museum Technician, which has lead me to make connections to the steps taken to preserve an analog photograph – such as keeping it in the fixative chemical bath for the right length of time so that the light does not deteriorate the print, or the never ending quest to avoid dust. In this way, I find that the analog process simply connects my practice.

Until next time,

– Becca Marshall