by Amy Zoethout | Aug 26, 2021 | Blog, Investigating Huron County History

Written by Exhibit & Programs Assistant Karsten

When hiking through or even driving past any of Huron County’s forests, you could easily believe that these forests have remained relatively unchanged for time immemorial. However, Huron County’s forests have had a long and, at times, tumultuous history.

Most of southwestern Ontario’s native tree species were in place by around 9000 BP, and until fairly recently, there was minimal disturbance of the local environment. The Anishinaabe inhabitants of what is now Huron County lived a primarily hunter-gatherer lifestyle, taking from the land only what was needed. This was supplemented with small garden plots in the summer. They also made extensive use of canoes, which of course did not require the forest clearing that roads do. Hunting, gathering, and navigating via the waterways are examples of a way of living which developed over centuries to work with the land, not against it. This is in stark contrast to how the land was used after European arrival.

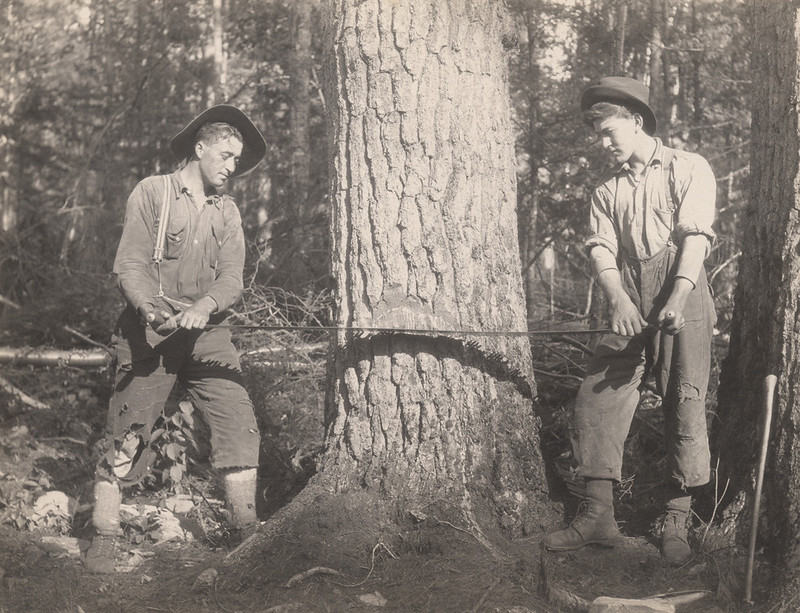

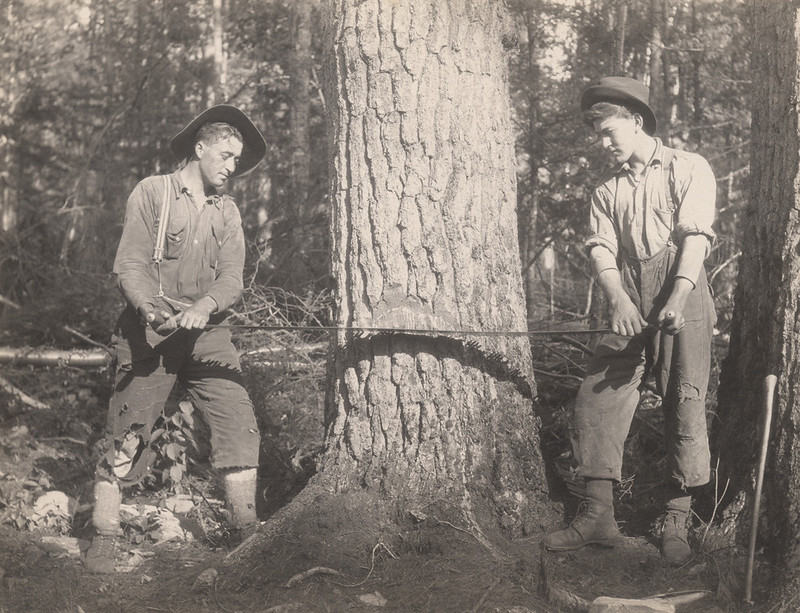

RR Sallows photograph of two men cutting a pine tree with a cross saw, 1917. 0362-rrs-ogohc-ph

European settlers began to arrive in the early 1800s. At that time the forests displayed a great diversity of species including oak, pine, cedar, sugar maple, yellow birch, swamp elm, beech-tree, white ash, black elm, red elm, viscous elm, walnut, butternut, “hollow-tree”, and cherry tree. In addition to having a great diversity of species, many of the trees are described as measuring 50 to 60 feet from the base to the lowest branches. The settlers quickly set about clearing the land to harvest timber and make farms, taking advantage of the “rights and responsibilities granted them as private landowners”. By the end of the 19th century, in an effort to build profitable farms and better lives for themselves and their families, European immigrants had cut down the vast majority of old growth forests throughout southern Ontario. Approximately 15 percent of Huron County is now forested, and much of that is the result of later conservation efforts.

RR Sallows photo of Tiger Dunlop Tomb, Gairbraid. Date unkown. 0346-rrs-ogohc-ph

By the late 19th century, the removal of forest cover, particularly around watersheds, was beginning to have harmful effects on agriculture in southern Ontario. In the summer, droughts would often last two to three weeks; in the winter, roads would have to be redirected over fields as they became impassible due to unimpeded blowing snow and drifting, which could bring about serious loss for the farmer. Realizing the necessity of forests, a few groups such as the Fruit Grower’s Association of Ontario (FGAO) began encouraging farmers to plant trees on their property, as well as lobbying for greater restrictions on cutting trees. In the case of the FGAO, attention was often placed on planting “natural fences” on the edges of farms. With an increasing popularity of scientific agriculture and growing influence of the Ontario Agriculture College, the following century would prove to show increased conservation efforts as understandings of ecosystems became more common. Moving into the first half of the 20th century, more groups formed and began working to increase the amount of forest cover in Ontario. Two of the most important were the Ontario Conservation and Reforestation Association (OCRA) and the Ontario Crop Improvement Association (OCIA), both forming in 1937 after a devastatingly warm summer.

RR Sallows photo of four farmers with teams of horses and implements working in field of peas from 1908. 0335-rrs-ogohc-ph

In Huron County, a testament to 20th century reforestation efforts is the 13 county forest tracts which total over 1,500 acres. Many of these tracts were donated by private landowners who were aware of the importance of the forests. These tracts provide environmental protection, as well as recreation for local residents. Another lasting result of these efforts is the tree bylaw, which was passed in 1947 with the support of farmers and landowners. This bylaw regulates the harvesting of trees in all woodlots which measure over half an acre in size.

Vast amounts of Huron County’s forests were lost in the process of colonization and farm-making. Thanks to historic and on-going conservation efforts though, approximately 15 percent of Huron County is currently forested. With that in mind, be sure not to take what you find for granted next time you visit one of Huron County’s forests.

One of the County’s forest tracts, the Robertson Tract, today.

Sources

Kuhlberg, Mark, ed. “Challenges, Conflicts and Cooperation: The Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry’s Complicated History with Ontario’s First Nations.” Forest History Society of Ontario. Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, 2017. http://www.ontarioforesthistory.ca/files/mnrf_history_relations_with_first_nations.pdf.

Plain, David D. A Brief History of the Saugeen Peninsula. Trafford Publishing, 2018.

Suffling, Roger, Michael Evans, and Ajith Perera. “Presettlement Forest in Southern Ontario: Ecosystems Measured through a Cultural Prism.” The Forestry Chronicle 79, no. 3 (May 2003): 486–87. https://doi.org/https://pubs.cif-ifc.org/doi/pdf/10.5558/tfc79485-3

Bowley, Patricia “Farm Forestry in Agricultural Southern Ontario, ca. 1850-1940: Evolving Strategies in the Management and Conservation of Forests, Soils and Water on Private Lands.” Scientia Canadensis 38, no. 1 (2015): 22–49. https://doi.org/10.7202/1036041ar

Pullen, David. “Forests For Our Future” Management Plan for the County Forests, Recommendations for Tree Cover Enhancement. Huron County, 2014. https://www.huroncounty.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Forest_For_Our_Future_2014-2033.pdf

Huron Stewardship Council, https://www.huronstewardship.ca/nature/forests/

Forestry Services, https://www.huroncounty.ca/plandev/forestry-services/

by Amy Zoethout | Jul 21, 2021 | Blog, Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History, Uncategorized

Kyra Lewis, Huron Historic Gaol outreach and engagement assistant, explores the architectural history of the Huron Historic Gaol.

The Huron Historic Gaol is a one of a kind building: predating Confederation, this anomaly has stood for over 181 years. Despite being made of predominantly stone and lumber, it has survived fires, being struck by lightning twice, and a tornado. However, its survival is not the only thing which stuns visitors about this incredible building. The Gaol’s architecture is one of the only of its kind in Canada standing today. This blog post will explore the architectural history of the Historic Gaol, and how and why its structural significance is honoured 181 years later.

Settlement began in Goderich as a result of the development of the Huron Tract in the 1830s; at the time, Goderich and the surrounding area were part of the London District. However, residents in the area felt disconnected from the district government and their affairs. Back then, in order to qualify as a County, you must possess a local government, and to do that, you had to have both a Courthouse and a Gaol. So in 1839, a contractor named William Geary began clearing land allocated by the Canada Company to build a Courthouse and Gaol, with the grand objective of establishing a local government for the County of Huron. The location was decided based on the fact that, at the time, the Gaol was situated outside the town. The location of the Gaol was considered ideal as it was distant enough to host undesirable residents, but still close enough to town for the convenience of court officials.

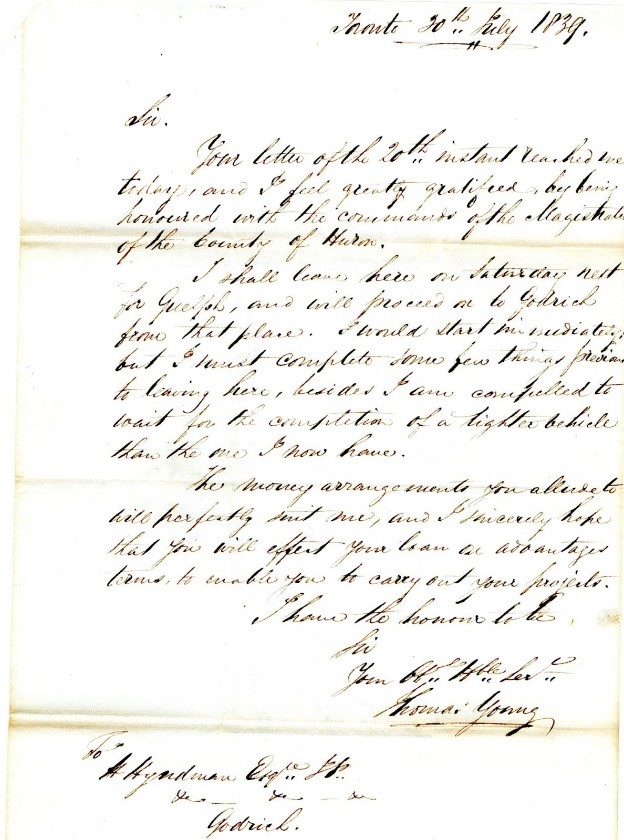

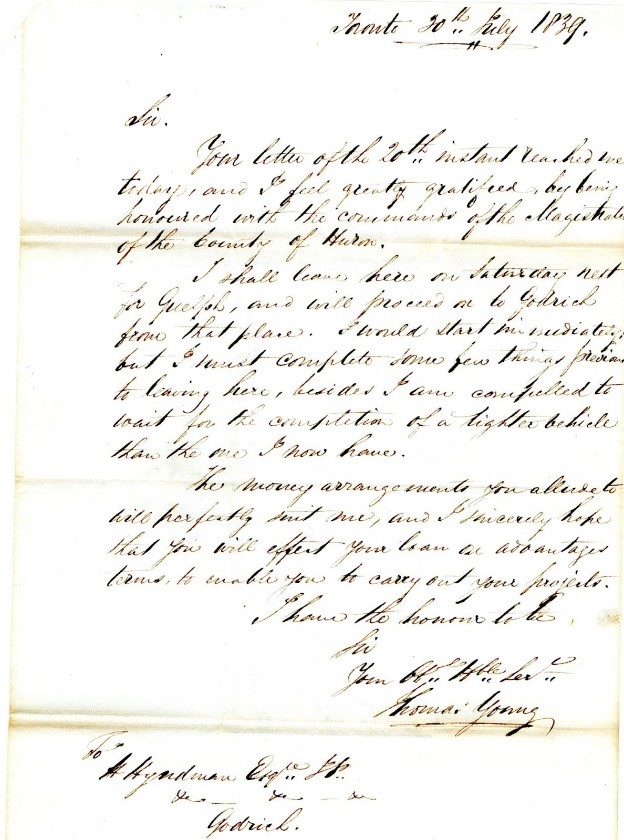

Letter from Thomas Young expressing his opinion and pleasure to take on the Gaol contract for Huron County.

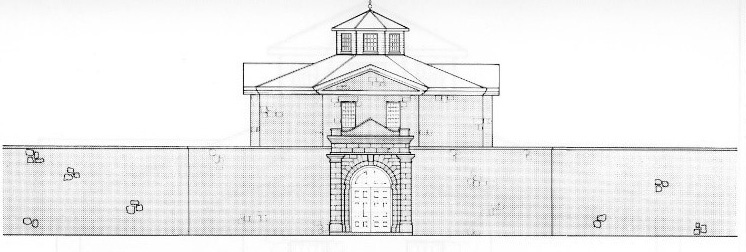

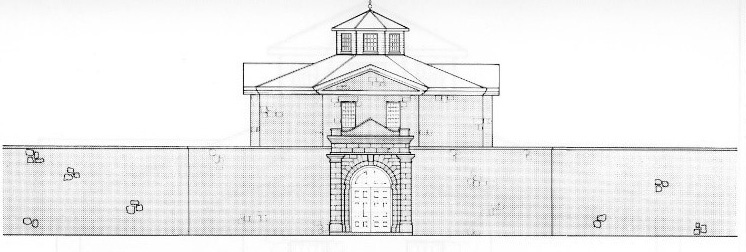

The project was given to Toronto architect Thomas Young. Young was born in England and had emigrated to Canada by 1834; until 1839 he was a drawing master at Upper Canada College. He received many commissions, one of which was to design King’s College in Toronto, which was completed in 1845. Young also received several other commissions between 1839-1844 to design, including the Wellington District Gaol and Courthouse, the Simcoe District Gaol, the Guelph Courthouse, and the Huron District Gaol. Many of Young’s designs were inspired by historic architecture, paying homage to neoclassical styles he utilized as an artist. This style consists of grandeur and symmetrical designs, similar to that of Roman and Greek buildings such as the Pantheon, located in Rome. Neoclassicalism became extremely popular in Italy and France in the mid 18th century, and was a very prominent influence in Young’s architectural designs and drawings.

Building materials for the Huron Gaol were sourced locally or imported via schooner from Michigan. A public posting requested “400 Cords of Stone – District of Huron Contract”, it was stated that the stone could be no less than “12 inches thick for the building of walls 2 feet thick”. This local stone came from the Maitland River, which flows through Huron County just to the north of the building. While local stone was used to construct the walls of the Huron Gaol, “coping and flagging” stone, which was predominantly used around the windows of the Gaol, was brought in from Michigan. Many other tenders were let for the project, such as 4,500 board feet of hewn timber, as well as blacksmith work and plastering.

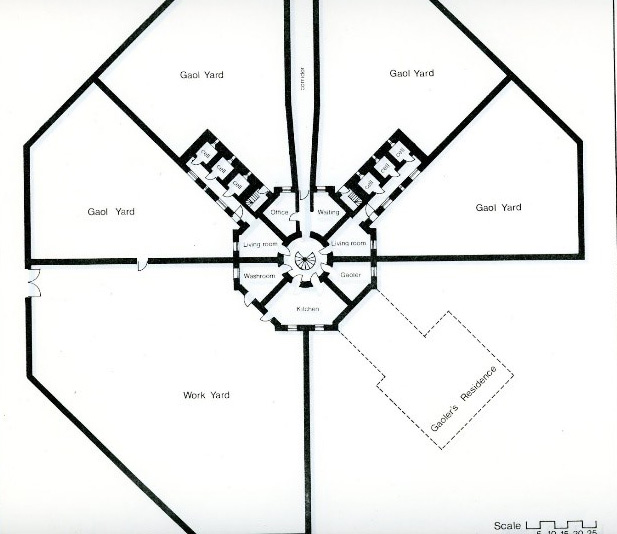

Drawing of the Huron Historic Gaol from Nick Hill’s report Huron Historic Gaol Goderich: A plan for restoration

PRISON REFORMATION

Young’s design for the Huron Gaol was inspired by Jeremy Bentham, an English philosopher. Bentham was devoted to reformation and rehabilitation and was curious about how prison design could contribute to the reform of criminals. Bentham popularized the panopticon, meaning “all seeing,” which precisely reflects the intention of the architecture. Panopticon designs allowed Gaol staff to observe prisoners from a centralized point, without the prisoners knowing when and if they are being observed. This structure was created to enforce compliance on prisoners, as they always had to act as though they were being watched. Due to the threat of constant surveillance, the theory of this design suggested that prisoners would then behave and conform to ideal behaviour. The invasiveness of always being able to be seen was stressful for prisoners, and thus they were more likely to comply with reformed behaviour. This was the intent of prison reformists such as Bentham, as their main objective was to create functional prisons that ran on limited manpower, but generated successful results concerning rehabilitation. Bentham believed that learning skills and completing tasks accurately and effectively while in a panopticon prison would ultimately contribute to their rehabilitation and readmittance into society as a better person.

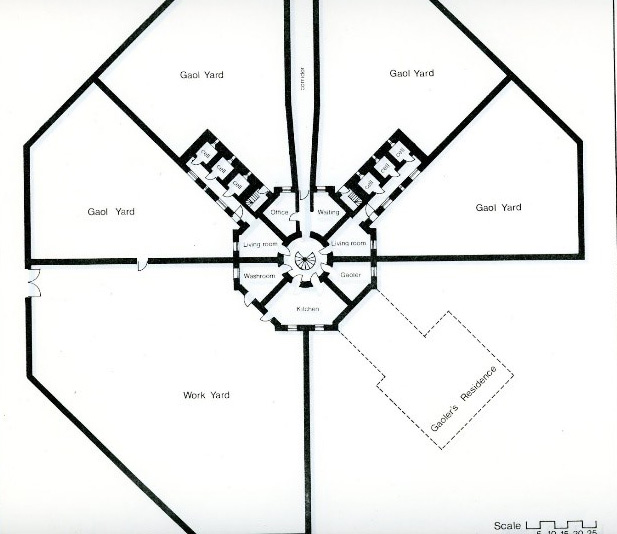

Drawing from report Huron Historic Gaol Goderich: A plan for restoration, by Nicholas Hill.

The panopticon was very prominent in the Gaol’s original design, as the Gaol itself has a centre building, with walls jutting out like spokes on a wheel. This was obviously intentional, as the third floor cupola allowed for staff to see each courtyard from one centralized point. Prisoners in the yards were therefore always observable, so there was an immense amount of pressure to behave. However, the cupola was not utilized nearly to the extent it would in a classical panopticon structure. The building’s courtyards were the only instance where panopticon design was implemented, as the rest of the building used a separate system. For this reason, the architecture still allowed for prisoners to have some sense of privacy and independence when in their cells. Thus Bentham’s ideology was not entirely encapsulated within Thomas Young’s design of the Huron Gaol, as only one aspect of the Gaol operated with this level of surveillance. Architect Nick Hill regarded this in his 1973 report to Huron County Council, mentioning that the design had “remarkable geometric clarity and functional arrangement based on the octagon”.

Another systematic influence that was used in the Huron Gaol’s design, was the separate system. This concept, oddly enough, was actually a contrast to the panopticon design. It enforces that prisoners stay isolated from one another, and can only be seen by guards when they enter the individual prison blocks. While the panopticon design was utilized in the structural elements of the courtyard, the separate system was incorporated within the Gaol’s cells. The act of keeping prisoners separate was significant as the Gaol was particularly small. This method ensured there would be fewer issues concerning fights and other conflicts amongst the prisoners. Solitude was also a major influence in many forms of prison reform around the 19th century. This form of confinement was designed to make prisoners easily controlled. Maintaining a sense of loneliness and isolation allowed for prisoners to feel more vulnerable and thus more compliant to the whims of the system they were incarcerated in. Eliminating that sense of unity and togetherness with other prisoners, in theory, would alleviate the possibility of revolts and violence as well.

The Huron Gaol implemented this in its cell design. There are four different cell blocks, with corresponding day rooms. Blocks one and two are on the first floor, with blocks three and four located on the second floor. The third floor, where the courtroom stands, has four individual holding cells. Every cell is oriented facing one direction, so other prisoners within the same block cannot see each other when in their individual cells. Historically, women and men were separated into different blocks, as mentioned in the Rules and Regulations of the Huron District Gaol detailed in 1846. This document stated that male and female prisoners were to be “confined in separate cells, or parts of the prison…as far as the dimensions, plan, and accommodations may allow”. At this point in time, prisoners were also separated into “classes” which were generally not permitted to intermix. For example: “1st. Prisoners convicted of felony. 2nd. Persons convicted of misdemeanors and vagrants. 3rd. Persons committed on charge or suspicion of felony. 4th. Persons committed on charge or suspicion of misdemeanors, or for what sureties; and in cases where necessity may require it, and circumstances admit, the sheriff may confine female prisoners in the rooms set apart for debtors. 5th. Debtors and persons confined for contempt of court on civil process.” The distance between each cell block also provided a sense of seclusion to ensure the safety of inmates.

The Gaol was a significant building for many reasons, however one of the most significant was the newly implemented techniques centred around prison reform. Prior to Jeremy Bentham and other incredible architects, sociologists, and philosophers, prisons were not based around reform. Prisons prior to the influence of such forward thinkers, were incredibly inhumane, as the concepts of rehabilitation and amelioration were relatively modern concepts in the early 1800s. There were a few gaols that implemented this philosophy, such as the Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, Auburn in New York State, as well as one in California. Thus, when Thomas Young utilized Bentham’s ideologies, it was one of the very first prisons existing at the time to be influenced by the new age philosophies of rehabilitation. Despite the Huron Gaol being of a much smaller scale, its design was truly revolutionary and ground breaking for its time.

Architect Nick Hill observed these concepts when he reflected on the Gaol’s structural uniqueness in the 20th century. Hill evaluated the significance of Bentham’s efforts of reform; “They engendered an attitude towards prisoners which saw the conclusion of exile, flogging, branding, maiming, the stocks and pillory, drawing and quartering.” The social changes these prisons inflicted on society were no small feat, as it signaled changing preconceived norms surrounding prisoners and criminal punishment.

Despite the Gaol’s incredible advancements in prison reform, there were several instances during its long history when councillors approved improvements be made to the Gaol to ensure functionality and proper treatment of prisoners. As there were no facilities for the elderly or the homeless until 1895 when the House of Refuge was constructed in Huron County, the Huron Gaol became a place of refuge for many. At its highest capacity, the Gaol held over 20 people, despite only having 12 cells and four holding cells. Its expansion became a necessity in order to ensure the Gaol was capable of executing the needs of all its inhabitants. For example, in July of 1853, the walls of the Gaol were deemed “insufficient for security” by the Grand Jurors. Despite this topic being brought to the Council’s attention in 1853, the Gaol walls were not expanded until July of 1861.

Aerial view of the Huron Historic Gaol showing walls as they stand today.

The renovation to the walls was undertaken after the Canada Company formally transferred the Gaol land to the County of Huron. Recommendations arising in 1856, following concerns around escapes from the Gaol, led to the walls being extended by two feet in height with loose stones being installed at the top of each wall. These stones were meant to come loose if a prisoner attempted to escape, causing them to fall to the ground when they grabbed a loose stone. William Hyslop was hired as contractor to renovate the walls, and was paid 27 pounds, 12 shillings, and 6 pence for “repairs to the Gaol wall”, as documented in council minutes from 1855. In the 1862 council minutes, William Hyslop is recompensed again for his efforts on the Gaol walls, after the County purchased the surrounding land to extend the walls outward, expanding the yard. The walls, as they stand today, are 18ft high and 2ft underground to ensure no prisoner could go over them or tunnel beneath. Other major improvements of the Gaol included the installation of a slate roof, as well as a bathtub in 1869. The original wooden bathtub was upgraded to copper in 1895 and a flush toilet was also installed. These changes were made for the health and well-being of the inmates, as health and hygiene were only recently being regarded as a necessity. Especially to avoid sickness and disease spreading through the relatively small facility.

The Huron Gaol has had an incredible 181 years of history in the County, and its captivating architecture represents incredible structural and architectural innovation for its time. The Huron Gaol is not only an incredible piece of history, but an amazing representation of the evolution of prison reform, rehabilitation and human rights.

Online Sources:

Primary Sources:

- H. Belden & Co. “Illustrated Historical Atlas of The County of Huron ONT: Compiled Drawn and Published from Personal Examinations and Surveys”. Toronto: 1879.

- Lizars, Daniel. “Rules and Regulations for the Huron Gaol 1846”. Rowsells and Thompson Printers. Toronto: July 24th 1846.

- Hill, Nicholas. Huron Historic Gaol Goderich: A plan for restoration prepared by Nicholas Hill. Undated.

by Amy Zoethout | Jun 23, 2021 | Blog, Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

Kyra Lewis, Huron Historic Gaol outreach and engagement assistant, explores how the Gaol dodged demolition.

Construction of the Huron Gaol began in 1839 in the Town of Goderich making it Huron County’s first municipal building. This once essential government building served as both a prison and a courthouse once its construction was completed, with the first documented prisoner committed on Dec. 3, 1841. The Gaol held significant value to the people of Huron County, as it represented their newfound independence from London District. The Gaol served as a focal point of justice and was where the Huron District Council held its first meeting on Feb. 8, 1842.

As time went on, the Gaol’s role began to shift; when the new courthouse was constructed in the centre of Market Square Goderich, in 1856, the Gaol’s sole purpose became holding prisoners. However, not all residents of the Gaol were criminals. Many who stayed at the Gaol were homeless, or mentally or physically ill. Drunkards, thieves, debtors and murderers lived alongside the homeless, and children as young as nine years old before Huron County Council constructed a House of Refuge in 1895. As time went on, numbers began to dwindle in the Gaol.

In 1968, The Children’s Aid Society moved into the Governor’s house after the last Governor moved out in 1967. The organization had outgrown their previously occupied space in the basement of the Courthouse located downtown Goderich. During the Children’s Aid Society’s time in the Governor’s house, they witnessed the closure of the Gaol in 1972 after the final prisoner was transferred out. However, prior to the Gaol even being closed as a facility, there was a proposal presented to the Huron County Council in September, 1971, to remove two of the Gaol’s walls adjacent to Napier Street to build a parking lot to accommodate the expanding services of the Children’s Aid Society and the Gaol’s neighbour, the Huron-Perth Regional Assessment Office. On Nov. 26, 1971, County Council received a formal approval from the Provincial Department for the demolition of certain walls at the County Gaol.

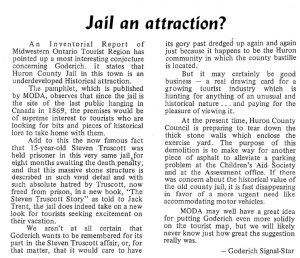

This decision provoked a massive response from the community and press, especially from Goderich and the surrounding areas. Many articles began appearing in the local newspapers concerning the possible preservation of the facility, as well as public rejection of the decision to tear the Gaol walls down.

Editorial as published in the Exeter Times-Advocate, Nov. 25, 1971

The papers referred to the old facility as an “underdeveloped historical attraction”, and “a real drawing card for a growing tourist industry”. However, Council at the time had no intention of utilizing the space as a Museum of Penology. Some councillors did not condone the county spending the money to restore the building, as it was projected the restoration would cost around $25,000. Other councillors believed that if they had that much money to spend, it should be allocated around the county, and not just in Goderich. Another drawback that was suggested was the glorification of previous inmates whose actions were heavily frowned upon. The potential of immortalizing the darker aspects of Huron County’s past was a genuine concern amongst officials.

The Property Committee eventually presented the County Council with another report on Dec. 8, 1972, which detailed the idea of the old Gaol becoming a “Museum of Penology”. However, in the same report they also put forth a recommendation to construct a parking lot and an extension for the Assessment Office, costing a projected $150,000. In January, 1973, Huron County Council approved the removal of three walls at the Gaol, after considering both the Children’s Aid office and the Assessment Office’s needs. The Gaol was unfortunately placed back on the chopping block, now set to lose another wall.

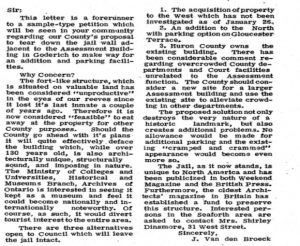

When citizens caught wind of the verdict, they were none too pleased with the potential defacement of such an iconic local building. More articles and letters to the editor began showing up in the papers and a small group of concerned citizens came together to fight to save the historic building. If the Gaol walls were to be torn down, it would completely ruin the integrity of the building’s design. As the Gaol’s architect, Toronto-born Thomas Young had been inspired by famed English philosopher and prison reformist Jeremy Bentham. Thus, the loss of the Gaol walls would compromise both the value and history of the structure, as they added an irreplaceable element to the significance of its layout and design. The goal of this growing group of local politicians, historians and volunteers was to pressure the Council into reassessing their decision to tear down the walls. Their arguments were intended to bring to light the necessity of the architectural, historical and cultural conservancy of the building. And so, the Save the Jail Society was born!

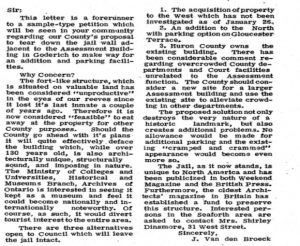

Letter to the Editor written by Joan Van den Broeck published in the Goderich Signal-Star.

With their objectives set, the group of dedicated members wrote letters to the newspaper, educating the public on their cause. A brilliant letter addressed to the editor of the Goderich Signal-Star was written by Save the Jail Society activist Mrs. Joan Van den Broeck. She advocated for the preservation of the Gaol, stating the uniqueness of the architecture as being one-of-a-kind, as well as miraculously structurally sound despite being around 130 years old, predating confederation. She also spoke of the building’s national and international notoriety, which would only enhance the tourist experience in Huron County. Van den Broeck, along with Goderich Reeve Paul Carroll and their fellow Save the Jail Society members, sought to change the fate of the iconic building.

The Save the Jail Society was extremely vocal and visible within the community, organizing campaigns at Goderich District Collegiate Institute and compiling a petition, as well as fundraising and rallies. There was a song written to commemorate the Gaol, which was written by Wingham entertainer Earl Heywood. The song was sung to the tune of Battle Hymn of the Republic, and was sung at events and rallies. They presented a petition to Huron County Council, as well as an architect’s revised plan for the parking lot to be built on the north side of the building. The group also threatened to pursue legal action if the demolition was to move forward.

One of the group’s most engaging events was an open house held at the Gaol on Feb. 19, 1973, which was initiated to motivate and engage the community in the cause to save the building. This event amassed a crowd of over 2,000 people who were all curious to explore the historic building and to find out what the big deal was about the Gaol. This event is what Save the Jail Society members would later reflect upon as a tide turner in terms of popular support. This event also made a massive impression from County Council’s perspective, as they were now aware of the appreciation the community held for the building.

Goderich Town Council met on April 12, 1973, in response to a letter issued from the County. This letter was a revision of the previous parking lot proposal designed by Nick Hill, which would allow for the Gaol walls to remain untouched. Finally, on April 26, 1973, Huron County Council agreed to the proposal by Goderich Town Council. This acceptance meant that the Save the Jail Society’s goal of saving the Gaol had been realized!

Once the safety of the Gaol had been ensured, the Save the Jail Society began to create an administration to govern the historic building. On May 1, 1974, the “Huron Historic Jail Board” was created. The Jail Board leased the building from the County for $1 per year for it to be incorporated as a Museum and Cultural Centre; it was opened to the public on June 29, 1974. The Jail board was finally legally incorporated on Oct. 13 of the same year. The Gaol was finally a Museum of Penology!

This great victory for the Save the Jail Society (now the Jail Board), was only the beginning for the Huron Gaol. On July 5, 1975, a massive celebration was held at the Gaol in Goderich to acknowledge the Gaol becoming designated a National Historic Site. The ribbon was cut to officially acknowledge the opening of the Huron Historic Gaol by Huron County Warden Mr. A. McKinley. The plaque detailing the Gaol’s historical significance was unveiled by none other than dedicated member Joan Van den Broeck.

This great victory for the Save the Jail Society (now the Jail Board), was only the beginning for the Huron Gaol. On July 5, 1975, a massive celebration was held at the Gaol in Goderich to acknowledge the Gaol becoming designated a National Historic Site. The ribbon was cut to officially acknowledge the opening of the Huron Historic Gaol by Huron County Warden Mr. A. McKinley. The plaque detailing the Gaol’s historical significance was unveiled by none other than dedicated member Joan Van den Broeck.

The reason the Huron Historic Gaol stands to this day is not simply because of its historical value. This building is a symbol of the strength and dedication of the people of Huron County. Despite being sentenced to be destroyed, the Gaol was saved by the efforts of ordinary Huron County citizens who fought to preserve their history. The Gaol is not only a building which represents law and order within the County, but a reminder of how the County was incorporated and achieved its own independent settler municipal government and identity. Huron County was created by strength and unity, it seems only fitting its history was also saved by it.

Sources

Explore these sources through the online collection of Huron Historic Newspaper.

- “Jail an Attraction?”, The Exeter Times-Advocate, Nov. 25, 1971, pg 4.

- “Save Jail Wall”, The Brussels Post, Jan. 31, 1973.

- “And the Walls Came Down…Maybe”, The Exeter Times-Advocate, Feb. 8, 1972, pg 4.

- “Huron Council Clears Removal of Jail Wall”, The Huron Expositor, March 1, 1973, pg 1.

- “Letters to the Editor by Mrs. D. W. Collier Komoka”, Clinton News Record, March 15, 1973, pg 7.

- The Huron Expositor, April 12, 1973, pg 19.

- “Huron Reeves Vote to Save”, The Brussels Post, May 2, 1973, pg 9.

- “At County Council: Reeves Vote to Preserve Huron’s Historic Jail”, The Huron Expositor, May 3, 1973. Pg 1.

- “Jail House Blues Still Bother County”, Clinton News Record, June 7, 1973, pg 3.

- “Reeves Reject Bid for Use of Huron County Jail”, The Brussels Post, July 4, 1973, pg 13.

- “Tenders Let for Office”, The Blyth Standard, July 18, 1973, pg 1.

- “The Huron Gaol”, The Huron Expositor, June 1, 1978, pg 13.

Archival Material

- “Commemoration of Huron County Gaol”, July 5, 1975, pg 1-2.

by Amy Zoethout | Oct 26, 2020 | Archives, Blog, For Teachers and Students, Investigating Huron County History, Uncategorized

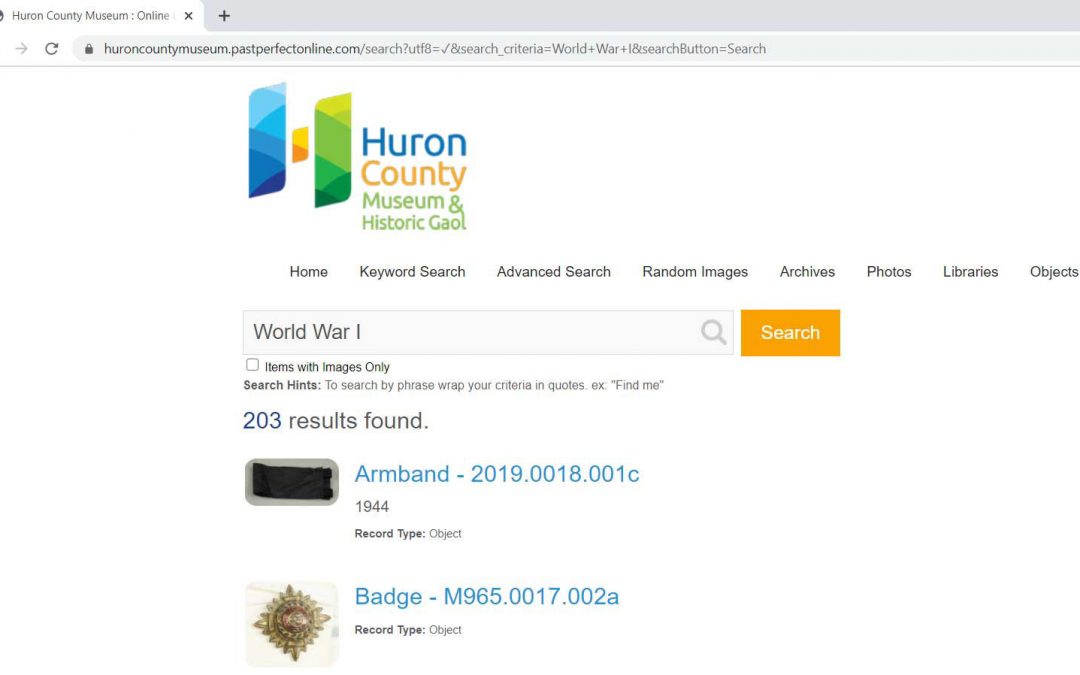

This military badge is from the Canadian Medical Corps worn on a Nursing Sister uniform by Maud Stirling, a First World War Nursing Sister. This artefact is one of more than 3,000 artefacts currently available on the Huron County Museum’s online collection.

by student Museum Assistant Jacob Smith

As a final year history student, I have grown accustomed to spending several hours preparing and writing essays. This is an important skill that takes years of practice. If you are developing an essay that is based on local history, the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol has several resources that can aid you in your studies.

The first research tool is the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol’s online collection, which can be found here. This is a database where the public can view over 5,000 artifacts and archival materials in the Museum’s collection. This tool provides background information on the artifacts, such as its provenance, dimensions, and past owners, and allows viewers to examine objects that are not currently on display. Examples of objects currently available in the collection include textiles, tools, personal items, furniture, photographs, documents, and much more.

Another excellent research tool is the Huron County Museum’s Digitized Newspapers. Here, researchers can glance at newspapers dating from the mid-1800s to the late-2010s. This database is free, easy to use, and accessible from the comfort of your own home! The digitized newspapers provide a vast wealth of information, ranging from local news and gossip, fashion, and global affairs.

The Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol also has an extensive archives collection. Here, researchers can locate coroner’s inquests, assessment rolls, court records, voter’s lists, and many more. By booking an appointment with the Archivist, researchers have access to a vast collection of resources, and a knowledgeable staff member to assist you.

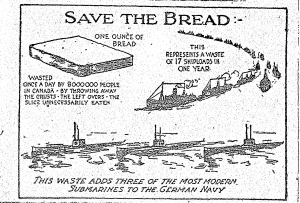

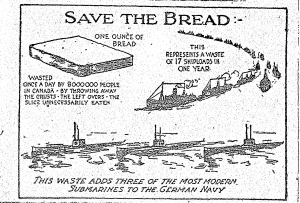

This World War I propaganda poster was found through the Huron County Museum’s digitized newspaper database (Source: The Exeter Advocate, 1918-8-22, Page 2).

A bonus resource! Ancestry.ca is a helpful tool that allows people to research, share information, and connect with others. Sources such as military death, and census records, images, and family trees. This source requires a paid subscription, but often has free trials that allows researchers to access its extensive content. Researchers can also access Ancestry Library Edition free from home until Dec. 31, 2020 with a Huron County Library card.

While writers may feel overwhelmed at the thought of composing a research essay, there are helpful resources close to home or even accessible without leaving home. With the Huron County Museum and Historic Gaol’s resources, writers have the exposure to a wealth of extensive resources, which are readily available from your personal computer. Keep these resources in mind when you are composing your research essay.

by Sinead Cox | Aug 25, 2020 | Archives, Blog, Exhibits, Image highlights, Investigating Huron County History

In anticipation of the Huron County Museum’s in-development exhibit Forgotten: People & Portraits of the County, volunteer Kevin den Dunnen takes an in-depth look at one of the many studio photographers to work in Huron County, and traces the professional and personal journey of Irene Burgess.

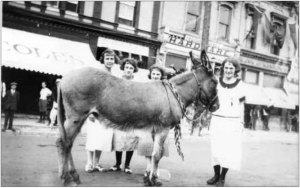

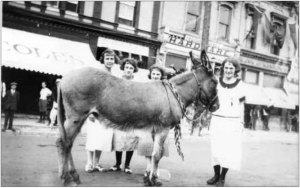

Summer of 1923 “old home week” in Mitchell, Ontario. Irene is the farthest left of the four. Image courtesy of the Stratford-Perth Archives.

Hiding within the Huron County Museum’s online and free-to-use newspaper archives are an unlimited number of stories like the one of Miss Irene Burgess. Irene Burgess was a woman that defied societal norms. In a time where women were rarely given the freedom to pursue a chosen career, Irene managed her own photography studio. While many women were expected to marry and have families, Irene stayed single. She was also faced with many tragedies in her life. Neither of her two siblings lived past 32. Her mother passed away at 51. Her niece nearly died at the age of 6. She lost the photography studio after an explosion. Through all of this, the communities of Perth and Huron Counties rose to support her.

Personal Life

Nettie Irene Burgess was born September 20, 1901, in Mitchell, Ontario. Her parents were Nettie and Walter Burgess. She had two siblings – an older sister named Muriel, born in 1896, and a younger brother named Macklin, born in 1912. Her father, Walter, was a long-time photographer in Mitchell and owner of W.W. Burgess Studio. Growing up around photography gave Irene plenty of exposure to the business. This experience would prove to be important in her adult life.

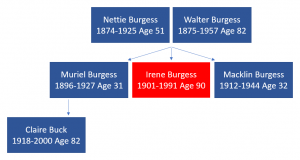

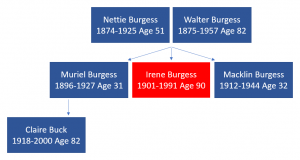

A brief family tree of the Burgess family. Of note, it only contains the names of family members included in this article.

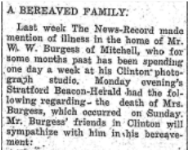

Excerpt from the November 26, 1925, edition of The Clinton News-Record detailing the passing of Irene’s mother Mrs. Nettie Burgess.

Irene experienced several tragedies throughout her life. By her 43rd birthday, only she and her father survived from their family of five. The first to pass was Irene’s mother, Nettie Helena Burgess, on November 22, 1925, at the age of 51. Irene’s sister, Mrs. D.F. Buck ( née Muriel Burgess) and her 6-year-old daughter Claire had been staying with her parents Walter and Nettie Burgess; Mrs. Buck had been ill for some time. During their stay, Claire became ill with pleuro-pneumonia. On the brink of death for several days, she began to recover with the help of her grandmother, Nettie. While caring for Claire, Nettie contracted pneumonia. Less than six days later, Nettie passed away in the presence of her family and nurse. 6-year-old Claire would live for another 75 years thanks to the care of her grandmother.

The next member of Irene’s family to pass would be her sister Muriel. Muriel was married to D.F. Buck, a photographer from Seaforth. They had three children, a daughter named Claire, and two sons named Craig and Keith. On March 24, 1926, an update in the Mitchell Advocate indicated that Irene would be visiting her sister, Mrs. D.F. Buck, at the Byron Sanitorium. According to the update, Mrs. Buck was “progressing favourably” but had been in poor health for some time. Almost fourteen months later on May 12, 1927, The Seaforth News wrote about the death of Mrs. D. F. Buck occurring the past Friday. While not mentioning the cause, the obituary described her as being “in poor health for a considerable period.”

On July 18, 1944, the Clinton News Record posted an obituary for Irene’s brother Macklin Burgess who passed away from a long-time illness at the age of 32. Macklin was in the photography and radio business. He left behind his wife, Elizabeth May, and three children, David, Nancy, and Dixie.

The next of Irene’s family to pass would be her father, Walter Burgess, in 1957 at the age of 82.

An interesting note in the life of Miss Irene Burgess is that she never married. In the Dominion Franchise Act List of Electors, 1935, Irene (age 34) is listed as a spinster (meaning a woman that is unmarried past the age considered typical for marriage). Whenever Irene is referenced in a newspaper, her title is Miss Irene Burgess. Irene would live until 1991.

The Clinton Studio

A notice posted by Walter Burgess in the May 23, 1929, edition of The Clinton News-Record

Walter Burgess operated a Clinton studio throughout the 1920s. The November 26th, 1925 edition of The Clinton News-Record mentions that Walter had only been spending one day a week at his Clinton Studio being “short of help.” A notice posted in The Clinton News-Record on May 23 1929 by Walter Burgess stated that his Clinton studio would only be open “the second and last Tuesdays in each month.” On October 1 of 1931, Walter announced that his newly-renovated Clinton studio would be open every weekday. His daughter, Miss Irene Burgess, would now be in charge of the location. Walter proclaimed Irene as “well experienced in Photography” and having “long experience with her father.” Not long after Irene became manager, Clinton residents would see the name Burgess Studios much more often in their newspapers.

When Irene began managing the Clinton Studio in 1931, advertisements for the business began increasing. The slogan “Photographs of Distinction” appeared in advertisements from 1937 until the week of the fire. These ads were brief, only including the business name, slogan, Irene’s name, and the services provided. Earlier advertisements include one from 1933: “It is your duty to have a good photograph. Your family wants it – business often demands it.” Another example from 1932 reads, “You have plenty of leisure time to get that portrait of [the] family group taken.” The Clinton studio began under the leadership of Walter W. Burgess, but Irene would soon grow the business larger than her father had the time for– that is, until the explosion.

Advertisement posted in the January 26, 1933, edition of The Clinton News-Record.

The Explosion

On the afternoon of Monday, November 24, 1941, an explosion set fire to the second story of the J. E. Hovey Drug Store sweeping the entire business block. This was the place of business for Burgess Studio, Clinton. The fire swept through the building and damaged several businesses including R. H. Johnson Jewelry Store, Charles Lockwood Barber Shop, and Mrs. A MacDonald’s Millinery and Ladies Wear Shop. Irene was not in the studio when the fire started and did not call the authorities. Instead, the fire was discovered by Police Constable Elliot who identified smoke around the second-story window of the J. E. Hovey Drug Store Building. The fire was well covered in local newspapers. Featured on the second page of the Seaforth News more than a week after the incident, it was reported that the fire almost reached the “main business section of the town.” On its front page the week of the accident, The Clinton News-Record described the fire as “one of the most dangerous Clinton firemen have fought for years.” Unfortunately, Irene did not have insurance and was forced to close her business in Clinton. An update written on November 27, 1941 in The Clinton News-Record mentioned Irene’s departure for Mitchell to stay with her father for an “indefinite time.” A week later, on December 4, 1941, Irene posted a notice in the News-Record reading that, “owing to the recent fire damaging my equipment and Studio, I will be unable to continue operation.” She suggested that customers could mail their orders to the new studio. Additionally, customers could drive to her father’s studio in Mitchell and have their travel expenses paid. While this time must have been devastating for Irene, the community came together to show their support for her.

Community Support

Excerpt from the December 12, 1941, edition of the Huron Expositor describing an even held in Irene Burgess’ honour.

Two weeks after the explosion, the Mitchell Advocate reported about an event held at the I.O.O.F. Hall where Irene was the “honoured guest.” The event was planned by Irene’s friends Mrs. Dalton Davidson, Mrs. Earl Brown, Mrs. Harold Stoneman, and Miss Florence Paulen. Entertainment included skits, piano music by Mrs. A. Whitney, cards, and a “bountiful lunch.” Irene received a “purse of money” and personal gifts from her friends along with their condolences. The rallying support for Irene shows the positive impact she had in the communities of Clinton, Seaforth, and Mitchell. An uplifting end to an otherwise sad story.

Conclusion

Aside from her brother’s passing in 1944, Miss Irene Burgess was seemingly never mentioned again in the Huron County Newspapers accessible through the digital newspaper portal. She would live until 1991 in St. Marys, Ontario.

Huron County’s digitized newspaper collection is a vast historical database where you can find historical stories from our own county. While performing research for the upcoming exhibit “Forgotten: People & Portraits of the County,” I came across this story which piqued my interest. Without access to the digitized newspaper collection, the story of Irene’s remarkable journey would never have been found. This post was compiled using newspaper articles between the years of 1925 and 1944. Birth and death dates were found within newspapers and using external resources.

If you have a photograph by a Huron County photographer you would like to donate or share, please contact the Museum’s archivist by calling 519-524-2686, ext. 2201 or email mmolnar@huroncounty.ca. To learn more about the Huron County Archives & Reading Room, visit: https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/huron-county-archives/

A950.1857.001 A photograph taken by Burgess Studio Mitchell in 1914. If you have a photograph from Burgess’ Studio, Clinton you would like to donate, please consider contacting the Huron County Museum.

by Sinead Cox | Jun 4, 2020 | Investigating Huron County History

Curator of Engagement and Dialogue Sinead Cox shares the story of a historical quarantine in the summer of 1916.

Although you may have heard (to the point of cliché) that we are living in ‘unprecedented times’ during today’s COVID-19 pandemic, communities across Huron County have seen quarantines and the temporary closure of schools and businesses before. Although usually on a much smaller and localized scale, these actions in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were in response to contagious illnesses that included influenza, measles, diphtheria, scarlet fever, smallpox, whooping cough and typhoid among others.

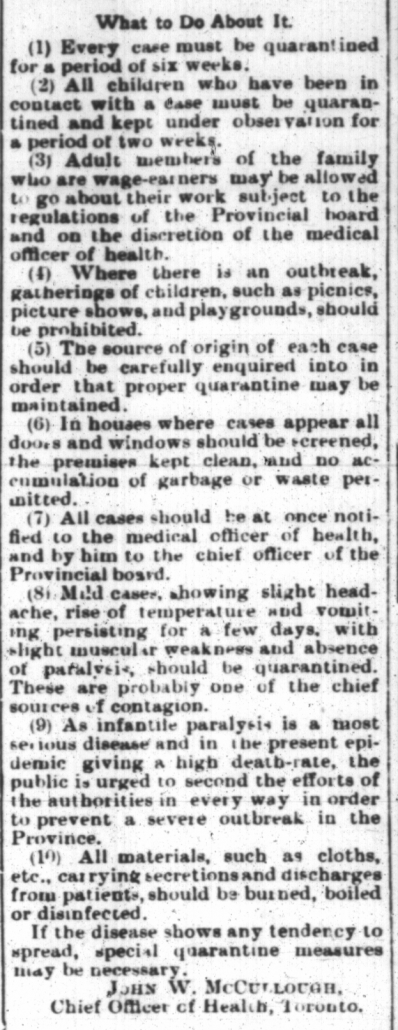

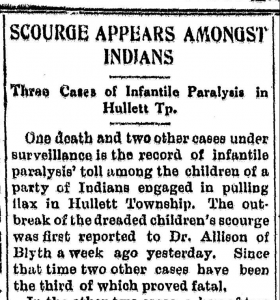

From The Brussels Post, July 27th, 1916.

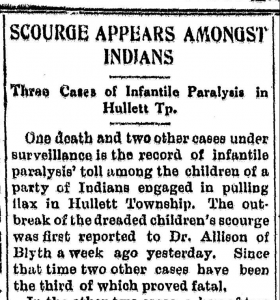

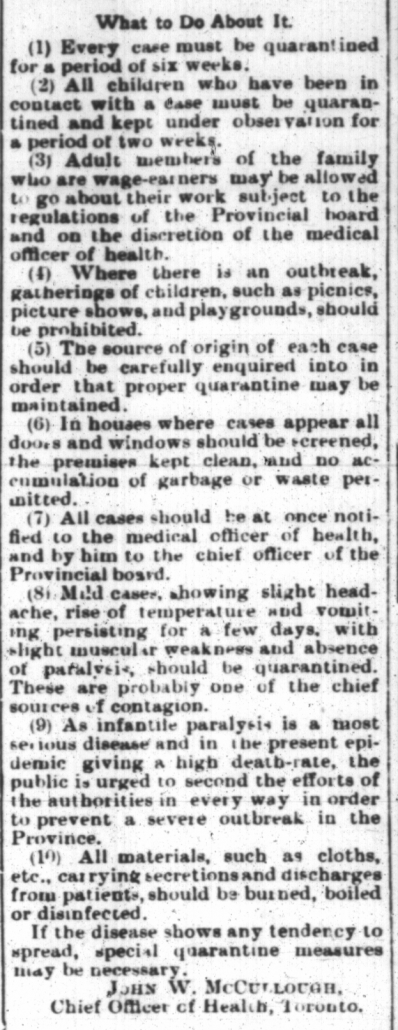

In 1916 an outbreak of infantile paralysis (polio or poliomyelitis) hit North America. The poliovirus is most dangerous to children under five years of age and in serious cases can cause permanent and debilitating nerve and muscle damage to survivors if non-fatal. The 1916 epidemic was particularly devastating in New York and then appeared in Canadian cities like Montreal before eventually arriving in southern Ontario. In Ontario, the provincial Medical Board of Health enacted quarantine regulations and required doctors to report all cases or face prosecution.

The outbreak had reached Huron County by July, when a fourteen-month-old girl in Varna died: only the second fatal case confirmed in Ontario up to that point. Panic hit the next month when three young children in Hullett Township contracted the much-feared disease. The children had come to live temporarily in Hullett (now part of the Municipality of Central Huron) with their parents during the flax harvest, but their permanent home was reported as ‘Muncey Reserve.’ Indigenous families from Southwestern Ontario reserve communities, including those on the shore of the Thames River south of London and also Saugeen First Nation to the north, were a crucial labour force for annual flax harvests in the early twentieth century. Entire families moved seasonally to pull flax for Huron growers; they worked and lived in close contact with each other, camping alongside their worksites.

The sick children belonged to a group of about 15 families living in tents roughly six miles from Clinton when the infantile paralysis struck-eventually infecting two five-year-olds and a two-year-old. A local Blyth doctor treated the first cases and told the area newspapers that the farm workers’ living situation presented a challenge for protecting the lives of the other 23 children in the camp: “Isolation and quarantine, so necessary for the treatment of infantile paralysis, are something hard to enforce in any Indian reservation or encampment…We are doing what we can to prevent any spread of the disease, and watching for further symptoms, but it is next to impossible to enforce the requisite isolation.” The vast majority of poliovirus cases are completely asymptomatic. The disease can spread through direct contact or via contamination by human waste.

From the Wingham Advance, August 31st, 1916.

For one of the five-year-olds, the virus was tragically fatal on August 25th, but the other two children soon appeared to be recovering. Local newspapers did not identify any of the camp members by name, but a death registration reveals that the little girl who lost her life was Annie Corneolus, the five-year-old daughter of Abram and Elizabeth. She was ill only one day, but the polio had caused lethal ‘paralysis of respiration.’ Her birthplace is recorded as Oneida Reserve (Oneida Nation of the Thames). Annie’s burial took place at Burns Cemetery, Hullett. Local health officials separated the families with sick children from the rest of their neighbours and they proceeded to quarantine at a farmer’s house on the 11th Concession. School Section # 11 at Londesborough cancelled classes for all students as a precaution.

Fortunately, their quarantine appeared successful and there were no further cases reported. The Clinton New Era announced that “the infantile paralysis scare in Hullett Township has pretty well blown over.” When health authorities lifted quarantine the families impacted returned to their reserve community, and the rest of the camp moved on to Blyth to continue their flax-pulling work. The Huron newspapers make no mention of whether or not the surviving children suffered any long-term health effects. Later reports listed the total number of province-wide infantile paralysis cases at 64 for July and August of 1916, with 8 resulting deaths–meaning that 25% of those total polio deaths occurred in Huron County.

From the Signal (Goderich), July 20th, 1916.

There is no cure for polio, but the Salk vaccine of 1955 would eventually be effective and widely used to prevent the disease; after continuous deadly outbreaks throughout the first half of the twentieth century, childhood vaccinations have eradicated polio in Canada.

The living and working conditions of temporary farm workers in 1916 would have made following advice about precautionary hygiene and social distancing almost impossible to follow-and many people in Canada are facing those same challenges today, without equal housing or opportunities to practice self-isolation under novel coronavirus. Although the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic is not the same as polio, the reality that Indigenous communities continue to be disproportionately impacted by pandemics, and that temporary and migrant workers are at a higher risk because of a lack of resources and opportunities to safely distance is absolutely precedented.

More Info about the history of polio in Canada: https://www.cpha.ca/story-polio

*Note: I wrote this blog post using contemporary newspaper accounts including the Wingham Times, The Wingham Advance, The Lucknow Sentinel, The Clinton New Era, The Clinton News-Record, the Signal (Goderich) and others, all accessed from Huron’s free historical newspaper database: https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers/ Annie’s death documentation was accessed via Ancestry.ca (Archives of Ontario; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Collection: MS935; Reel: 220). All of these accounts were written from a settler point of view (as is my own), and the newspapers did not include the voices or even the names of the community members impacted. If you have any further information you’d like to share about this outbreak or similar outbreaks in the past contact museum@huroncounty.ca.