by Sinead Cox | May 15, 2020 | Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

In this two-part series, Curator of Engagement & Dialogue Sinead Cox illuminates how the Second World War entered the walls of the Huron Historic Gaol. Click here for Part One: The ‘Defence of Canada’ in Huron County.

In the summer of 1940, when the Netherlands fell to Nazi Germany, a ripple effect extending to the Great Lakes would unexpectedly commit thirteen “alien seamen” to the Huron Jail.*

At the outset of the Second World War in 1939, the Oranje Line, also known in Dutch as Maatschappij Zeetransport N.V, was a relatively new Dutch-owned transport company that serviced Great Lakes routes. The Line had only commenced operations in 1937, and its fifth vessel in the Great Lakes, the 2,800 ton diesel freighter Prins Willem III was the first deep sea motor ship to come inland; she embarked on her maiden voyage in September, 1939.

On May 9th, 1940 the Prins Willem III departed neutral Antwerp, Belgium on a routine commercial journey under Captain W. P. C. Helsdingen. In the course of one day, the ship’s professional routine would be abruptly shattered. The Prins Willem III was off the coast of Flushing when a German bomb hit the water about 200 yards from the ship and caused a huge explosion and towering pillar of water. Germany had invaded the Netherlands. Planes were flying high and out of sight, but the crew could hear the whining sound of bombs as they fell nearby. Targeted by a machine gun onslaught from Nazi fighter planes, the ship escaped via the English channel. After narrowly surviving with their lives and the boat intact to reach England, the Dutch crew would soon learn that the formerly neutral Netherlands had capitulated and their home country was now occupied by Nazi Germany.

The ship continued on its planned journey to North American waters, docking at Montreal, Duluth, Milwaukee and finally Chicago on June 25th , successfully delivering a cargo of seeds and twine. At Chicago, the crew awaited orders regarding their next destination. Meanwhile, members of the Dutch government, including Queen Wilhelmina, had fled to London, England. The government in exile required all Dutch merchant vessels abroad to now sail under the British Merchant marines, and to report to an allied port to join the war effort: which could include transporting provisions or armaments. Canada being the closest allied country, the Netherlands Shipping Commission ordered the Prins Willem III to return to Montreal and “then embark for some unnamed foreign port,” according to the Chicago Daily Tribune. 17 out of the 19 crew members refused the orders.

The crew’s actions seemed to defy easy categorization as conscientious objection or mutiny. Captain Helsdingen assured the Chicago press that the men were neither striking, mutinous, nor even refusing to do their assigned jobs aboard the ship, but the crew would not leave the neutral waters of the United States (which would not enter the war until after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December, 1941). After their ordeal at the mercy of German bombs and guns, reluctance to return to a war zone aboard a ship that was not armed, and would not be provided an armed convoy, is hardly surprising. The Tribune quoted the crew as telling the captain, “If we cannot have weapons, we would rather spend our time in a United States jail than on the ocean.” They also feared for their families in a Nazi-occupied country and whether there could be reprisals against them—extending to arrests and transportation to concentration camps—for helping the allied cause by transporting munitions. According to the captain, the crew of the Prins Willem III feared Germany more than England.

The crew’s ‘sitdown strike’ left Commonwealth, Dutch and American authorities with no easy solutions. The standstill left most of the crew trapped on the ship, with only Captain Helsdingen legally permitted to go ashore. The crewmembers had no immigration documents to legally enter the United States, and because of the ongoing occupation of the Netherlands, the U.S. would not have been easily able to deport the sailors: thus Immigration authorities and the Coast Guard kept a close watch on the ship. The Captain could not take on an American crew to move the ship because of U.S. neutrality, and thus the Prins Willem III remained anchored unmoving at Navy Pier.

American newspaper reports emphasize that, rather than any assumed violent mutiny, the crewmembers were largely friendly and cheerful in their refusal to budge. During their months of isolation on board, the crew busied themselves cleaning, stripping and painting the masts, booms and deck, oiling “everything in sight, from door handles to winches,” and polishing every “spot of brass on the boat to glisten.” The Tribune declared when it finally left Navy Pier the Prins Willem III would probably be “the best painted, best oiled and best polished ship that ever left this port.” By September the crew’s plight had gained the sympathies of Dutch Chicagoans, who organized a committee to deliver care packages to the crew from pleasure boats.

The Dutch government-in-exile, the Oranje Line and Canadian authorities finally devised a solution in October: the Prins Willem III would take on a Canadian crew recruited from Montreal. Ten private police from the Pinkerton Detective Agency in the United States were hired to come aboard the ship with the fourteen Canadian crew-members to prevent resistance or sabotage, and the ship was escorted by the U.S. Coast Guard during its departure from Chicago. There was ultimately no violence from the crew confined below deck; according to Time Magazine, “internment in Canada looked better to the bored, sequestered Dutch than gazing at the Chicago skyline all day.” Their initial stop according to the American reports was to be an “unannounced Canadian destination,” later specified as an “Ontario Port.” That port was Goderich.

Ships in Goderich harbour, date unknown Photographer: Reuben R. Sallows (1855 – 1937)

On October 16th, 1940 the Prins Willem III—presumably painted, oiled and polished to perfection—arrived in the Goderich harbour. The secrecy surrounding the chosen port for the uncooperative crew’s disembarkment meant local customs workers were completely surprised by the ship’s unscheduled arrival, and began a tentative dialogue with Captain Helsdingen regarding next steps while further instructions from Ottawa were awaited. Again, the original crewmembers of the Prins Willem III were stuck in limbo on board, and again they made the most of it: according to the Clinton News-Record they came on deck “under the watchful eye of two [Pinkerton] detectives…getting great enjoyment out of perch fishing from the stern of the ship while they whistled modern American airs.” A local crowd of curious onlookers gathered at the harbour to gawk at the ship from a distance, and a host of exaggerated rumors quickly travelled throughout the community, including that the crew were held in irons and guarded by machine gun-wielding “G-men.”

Three days later, thirteen crew members quietly disembarked from the ship during the night, escorted by the RCMP in batches of no more than two men at a time.** Police vehicles delivered these men to the Huron Jail. The remaining crew changed their minds and agreed to sail with Captain Helsdingen and the Canadians. The Prins Willem III had vanished from the Goderich harbour by the next morning, and the Pinkerton Detectives caught a train back to Chicago.

Cell in the Huron Historic Gaol.

The crew’s confines on land might have been somewhat tighter and less comfortable than their previous situation on board the Prins Willem III. Detailed inmate records are not accessible from the 1940s, but regardless of how many prisoners were already ‘guests of the county’ at the time, the arrival of thirteen ‘alien seamen’ would have left the Huron Jail, which has only twelve cells, over-capacity and somewhat crowded. The crew, who may not have all spoken fluent English, would have received daily food rations worth 13 ¼ cents per inmate and would only be able to take fresh air from inside the jail’s walled courtyards.

The thirteen Dutchmen remained in jail for three weeks, until removed under RCMP guard on the afternoon of Saturday, November 9th; they left Goderich by rail. Their destination upon leaving Huron County was once again a mystery to the media and the public, but widely assumed to be a Canadian internment camp, where POWs, Jewish refugees from Europe, and civilian ‘enemy aliens’ of differing loyalties could be forced to cohabitate.

Captain Helsdingen and the Prins Willem III continued on to Montreal to enter into the service of the allies as originally ordered by the Dutch government-in-exile so many months earlier. The temporary Canadian replacements would eventually be relieved by a Dutch crew, and the boat outfitted with anti-aircraft guns and machine guns, but the Captain was to face continued refusals of work from his crew throughout the war. Confirming the original crew’s fears, an aerial torpedo struck the Prins Willem III off the coast of Algiers in March, 1943; the ship later capsized and sank, resulting in eleven deaths. None of the original crew from the Chicago sojourn were amongst the lives lost.

The international incident caused by the Prins Willem III in the Great Lakes may be largely forgotten today, but the plight of its crew demonstrates that the North American homefront was not always as peaceful or untouched by the conflict in Europe as we might imagine. Overnight, the capitulation of the Netherlands had left the crew of the Prins Willem III in a precarious situation after enduring a surely traumatizing ordeal during the Nazi invasion on May 10th, 1940. Facing uncertainty in the custody of North American authorities, versus what they might have deemed as an almost certain death re-entering a war zone without adequate protections, they took action (or rather inaction) that stymied multiple governments and brought the repercussions of the Second World War to an ‘Ontario Port’ as apparently nondescript as ours.

*A note on spelling: Jail & gaol are alternative spellings of the same word, pronounced identically. Both spellings were used throughout the history of the Huron Historic Gaol fairly interchangeably. Although as a historic site the Huron Historic Gaol uses the ‘G’ spelling more common to the nineteenth century, for this article I have chosen to employ the ‘J’ spelling that appeared more consistently in the 1940s.

** Newspaper reports record 16 crew members jailed, but the Jailer’s Report to Council for 1940 recorded 13 “alien seamen,” and this is also the number given by Martine van der Wielen-de Goede, who reviewed crewmembers’ testimonies later in London (see sources below).

Special thanks to Alana Toulin & Christina Williamson for research assistance that made this blog post possible!

Further Reading

Internment in Canada via the Canadian Encyclopedia: https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/internment

Internment resources from Library and Archives Canada: https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/politics-government/Pages/thematic-guides-internment-camps.aspx

Secondary Sources

Gillham, Skip, “The Oranje Line,” Telescope, Volume XXX, No. 5. (Sept-Oct 1981), pg 116-117.

Malcolm, Ian M, Shipping Losses of the Second World War, (Brinscombe Port Stroud: The History Press, 2013).

van der Wielen-de Goede, Martine, “Varen of brommen Vier maanden verzet tegen de vaarplicht op de Prins Willem III, zomer 1940,” Tijdschrift voor Zeegeschiedenis, No. 1 (Jan. 2008) Via https://docplayer.nl/173449011-Ten-geleide-tijdschrift-voor-zeegeschiedenis.html

Sources: Articles

“At Sea: Open Lanes.” Time Magazine, October 21, 1940, pg 29.

“Canada Jails 16 Dutch Seamen After Mutiny.” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 11, 1940.

“Dutch Crew Jailed.” The Wingham Advance-Times, October 17, 1940.

“Dutch Sailors Removed.” Huron Expositor, November 15, 1940.

“Dutch Sailors to Jail.” Clinton News-Record, October 24, 1940.

“Dutch Freighter Arrives in Goderich.” Clinton News-Record, October 17, 1940.

“Escapes Bombing; Reaches Chicago: Unloads Seeds, Twine.” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 27, 1940.

“Explains Dutch Sailors’ ‘strike’: They Fear Nazis.” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 28, 1940.

“Members of Crew Interned.” The Seaforth News, October 17, 1940.

“Sitdown Strike Strands Dutch Ship in Chicago.” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 26, 1940.

“Stranded Dutch Ship Sails with Canadian Crew: Idle Force Lets Sailors Aboard Quietly.” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 8, 1940.

“Strikers Mark Time.” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 27, 1940.

Wilson, Edward. “Aye, There’s Rub to Life Aboard Dutch Freighter: Crew Keeps Busy Polishing and Painting Ship.” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 7, 1940.

by Sinead Cox | May 7, 2020 | Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

In this two-part series, Curator of Engagement & Dialogue Sinead Cox illuminates how the Second World War impacted Huron County in unexpected ways at home, and even entered the walls of the Huron Historic Gaol. Click for Part Two, and the strange tale of how Dutch sailors became wartime prisoners in Huron’s jail.

During the Second World War, Canada revived the War Measures Act: a statute from the First World War that granted the federal government extended authority, including controlling and eliminating perceived homegrown threats. The Defence of Canada Regulations implemented on September 3, 1939 increased censorship; banned particular cultural, political and religious groups outright; gave extended detainment powers to the Ministry of Justice and limited free expression. In Huron County, far from any overseas battlefields, these changes to law and order would bring the Second World War closer to home.

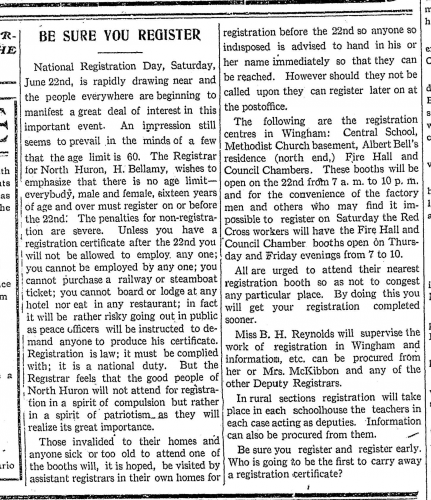

Regulations required Italian and German-born Canadians naturalized as citizens after 1929 (expanded to 1922 the following year) to formally register as ‘enemy aliens’ and report once a month. In Huron County, jail Governor James B. Reynolds accepted the appointment of ‘Registrar of Enemy Aliens’ in the autumn of 1939, and the registration office was to operate from the jail in Goderich. There were also offices in Wingham, Seaforth and Exeter managed by the local chief constables of the police force.

Regulations required Italian and German-born Canadians naturalized as citizens after 1929 (expanded to 1922 the following year) to formally register as ‘enemy aliens’ and report once a month. In Huron County, jail Governor James B. Reynolds accepted the appointment of ‘Registrar of Enemy Aliens’ in the autumn of 1939, and the registration office was to operate from the jail in Goderich. There were also offices in Wingham, Seaforth and Exeter managed by the local chief constables of the police force.

In addition to its novel function as the alien registration office, the Huron Jail also housed any prisoners charged criminally under the temporary wartime laws. Inmate records from the time period of the Second World War cannot be accessed, but Reynolds’ annual reports submitted to Huron County Council indicate that one local prisoner was committed to jail under the ‘Defence of Canada Act’ in 1939, and there were an additional four such inmates in 1940. The most common charges landing inmates behind bars during those years were still typical for the county: thefts, traffic violations, vagrancy and violations of the Liquor Control Act (Huron County being a ‘dry’ county).

Frank Edward Eickemier, the lone individual jailed under the War Measures Act’s Defence of Canada regulations in 1939, was no ‘alien,’ but the Canadian-born son of a farm family in neighbouring Perth County. Nineteen-year-old Eickemier pled guilty to ‘seditious utterances’ spoken during the Seaforth Fall Fair, and received a fine of $200 and thirty days in jail (plus an additional six months if he defaulted on the fine). The same month the Defence of Canada regulations took effect, Eickemier had publicly proclaimed that Adolph Hitler’s Nazi Germany was undefeatable, and that if it were possible to travel to Europe he would join the German military. He fled the scene when constables arrived, but was soon pursued and arrested for “statements likely to cause disaffection to His Majesty [King George VI] or interfere with the success of His Majesty’s forces.” His crime was not necessarily his political views, but his disloyalty. The prosecuting Crown Attorney conceded, “A man in this country is entitled to his own opinion, but when a country is at war you can’t go around making statements like that.”

Bruce County law enforcement prosecuted a similar case in July of 1940 against Martin Duckhorn, a Mildmay-area farm worker employed in Howick Township, and alleged Nazi sympathizer. Duckhorn had been born in Germany, and as an ‘enemy alien’ his rights were essentially suspended under the War Measures Act, and he thus received an even harsher punishment than Eickemier: to be “detained in an Ontario internment camp for the duration of the war.”

Huron County Courthouse & Courthouse Square, Goderich c1941. A991.0051.005

In July of 1940, the Canadian wartime restrictions extended to making membership in the Jehovah’s Witnesses illegal. The inmates recorded as jailed under the ‘Defence of Canada Act’ in Huron that year were likely all observers of that faith, which holds a refusal to bear arms as one its tenets, as well as discouraging patriotic behaviours. That summer, two Jehovah’s Witnesses arrested at Bluevale and brought to jail at Goderich ultimately received fines of $10 or 13 days in jail for having church publications in their possession. Four others accused of visiting Goderich Township homes to discourage the occupants from taking “any side in the war” had their charges dismissed—due to a lack of witnesses. In 1943, the RCMP and provincial police collaborated to arrest another three Jehovah’s Witnesses in Goderich Township for refusing to submit to medical examinations or report their current addresses (therefore avoiding possible conscription); the courts sentenced the three charged to twenty-one days in the jail, afterwards to be escorted by police to “the nearest mobilization centre.”

By August of 1940, an item in the Exeter Times-Advocate claimed that RCMP officers were present in the area to ‘look up’ those individuals who had failed to comply with the law and promptly register as enemy aliens. A few weeks later, the first Huron County resident fined for his failure to register appeared in Police Court. The ‘enemy alien’ was Charles Keller, a 72-year-old Hay Township farmer who had lived in Canada for 58 years, emigrating from Germany as a teenager in 1882. According to his 1949 obituary in the Zurich Herald, Keller was the father of nine surviving children, a member of the local Lutheran church, and had retired to Dashwood around 1929. His punishment for neglecting to register was not jail time, but the fine of $10 and costs (about $172.00 today according to the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator).

Although incidences of prosecution under the ‘Defense of Canada Act’ in Huron County were few, the increased scrutiny and restrictions would have been felt in the wider community, especially for those minority groups and conscientious objectors directly impacted. Huron had a notable number of families with German origins, especially in areas like Hay Township where you can still see the tombstones of many early settlers written in German. The Judge who sentenced Frank Edward Eickemier for his public support of the Nazi regime in 1939 made a point of accusing him of casting a ‘slur’ on his ‘people’ and all German Canadians: the actions of the individual conflated with a much larger and diverse German community by a representative of the law. His case indicates that pro-fascist and pro-Nazi sentiment certainly did exist close to home, but a person’s place of birth or their religion was not the crucial evidence that could define who was or was not an ‘enemy.’

Next Week: Click for Part Two, and the strange tale of how stranded Dutch sailors ended up prisoners in the Huron County Jail during the Second World War.

*A note on spelling: Jail & gaol are alternative spellings of the same word, pronounced identically. Both spellings were used throughout the history of the Huron Historic Gaol fairly interchangeably. Although as a historic site the Huron Historic Gaol uses the ‘G’ spelling more common to the nineteenth century, for this article I have chosen to employ the ‘J’ spelling that appeared more consistently in the 1940s.

Further Reading

The War Measures Act via the Canadian Encyclopedia

Sources

Research for this blog post was conducted largely via Huron’s digitized historical newspapers.

“Faces Trial on Charge of Making Disloyal Remark.” Seaforth News, September 28, 1939.

“German Sympathizer Interned.” The Wingham-Advance Times, July 25, 1940.

“In Police Court.” Seaforth News, August 29, 1940.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Charged.” Zurich Herald, October 21, 1943.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Fined at Goderich.” The Wingham-Advance Times, August 22, 1940.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Refused Bail.” The Wingham Advance-Times, July 18, 1940.

“Looking Up Aliens Who Failed to Register.” The Exeter Times-Advocate, August 1, 1940.

“Police Arrest ‘Jehovah’s Witnesses.’” Seaforth News, June 27, 1940.

“Statement He Would Fight for Hitler Proves Costly.” The Wingham-Advance Times, October 5, 1939.

“To Register German Aliens.” The Seaforth News, October 12, 1939.

“Twenty-One Days.” The Lucknow Sentinel, October 28, 1943.

“Would Fight for Hitler-Arrested.” The Wingham Advance-Times, September 28, 1939.

by Sinead Cox | Apr 27, 2020 | Blog, Investigating Huron County History

Patti Lamb, museum registrar, outlines Huron County’s connection to the Disney legacy.

While most of us know the impact that Walt Disney has had on the entertainment world; whether that be through the amusement parks that bear his name or the children’s movies that we all love; few realize that his ancestral roots lie in Huron County. The connections in Huron County to Disney are rooted with his ancestors but modern day connections still exist.

Ancestral Connections

In 1834, Walt’s great grandfather Arundel Elias Disney, wife Maria Swan Disney and 2 year old Kepple Elias Disney; along with older brother Robert Disney and his wife, sold their properties in Ireland, departed from Liverpool, England and immigrated to America landing in New York on October 3, 1834. According to a written biography by Walt’s father there were 3 brothers that immigrated at the same time. The brothers went into business in New York while Elias (as he was most commonly called) made his way to Upper Canada settling in Goderich Township near Holmesville. By 1842, Elias had purchased Lots 38 and 39 on the Maitland Concession, a tract of land comprising of 149 acres. There, along the Maitland River, on Lot 38 he built one of the earliest saw and grist mills in the area. Brother Robert eventually purchased 93 acres on Lots 36 and 37 of the same concession. Elias and Maria had 16 children.

James and Ann (Swanson) Munro were among the first settlers in the Holmesville District and James was the first blacksmith in Holmesville (1834 – 1871). The base for this table is made from a birch stump that he selected from his 36 acre property (Lot 83, Maitland Concession) which he purchased August 15, 1832. The original 5 roots serve as legs. The top is of cherry lumber, sawn from some of the first logs to go through the saw mill owned by Elias Disney (great grandfather of Walt Disney). On the underside is carved the name “Emily” for one of James and Ann’s 12 children.

N7143.001b

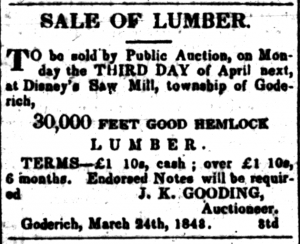

Advertisement for the sale of lumber from the Disney Saw Mill from the Huron Signal, March 24, 1848.

On March 18, 1858, Kepple Disney (Walt’s grandfather) married Mary Richardson, whose family were also early Goderich Township settlers near Holmesville. They purchased a farm on Lots 27 and 28 of Morris Township near Bluevale. Kepple and Mary had 11 children of which Elias Charles Disney (Walt’s father) was the oldest, born on February 6, 1859 in Bluevale and baptized in St. Paul’s Church in Clinton. All 11 children would eventually attend Bluevale Public School. Kepple did not really enjoy farming. He liked to travel and became intrigued in the drilling industry so in 1864, while keeping the homestead in Morris Township, he moved his family to Lambton County. He stayed in Lambton for 2 years before arriving in Goderich.

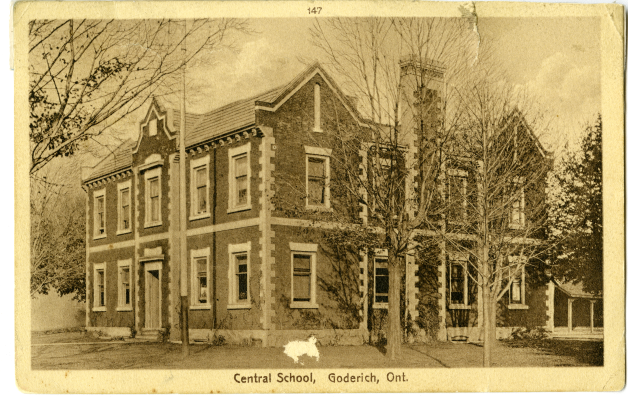

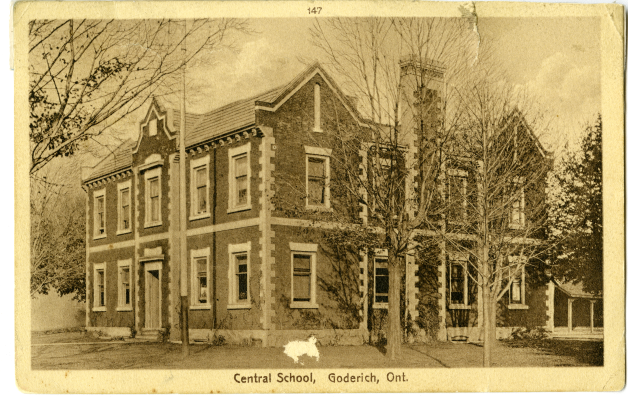

Here, Kepple was employed by Peter MacEwan and worked for him drilling for oil at a well in Saltford, just north of Goderich. Instead of oil, it was salt that was discovered, but that’s another story. In the July 1868 Voter’s List, the Disney’s appear as tenants of a house owned by James Whitely on Lot 275 in St. David’s Ward, Goderich. School records show that in 1868, 8 year old Elias and 6 year old Robert would attend Central Public School in Goderich (now part of the Huron County Museum). It appears the Disney’s left Goderich and moved back to the homestead in Morris Township sometime before 1869.

Postcard of Central School, N3103.

In 1878, Kepple left for California, where gold had been found, taking with him his oldest sons Elias and Robert. They stopped over in Ellis, Kansas and purchased 200 acres. Kepple sent for the rest of his family and his property in Morris Township was sold.

Ellis, Kansas is where Elias met neighbour Flora Call and on January 1, 1888 they were married. Kepple Disney’s family moved to Florida in 1884 and Elias, Flora and son later moved to Chicago. On December 5, 1901, Walter Elias (Walt) Disney was born, the 4th child of 5 for Elias and Flora Disney. After living in Chicago for 17 years, when Walt was 5 the family moved to Maceline, Missouri. They lived there for four years before moving onto Kansas City, Kansas.

At age 18, Walt started work as a commercial artist and from 1920 – 1922 was a cartoonist. He moved to Hollywood and opened a small studio (Walt Disney Studios) in 1923. He married Lillian Bounds on July 25, 1925 who was working for Walt Disney Studios at the time. The Disneys later had two daughters, Diane Marie and Sharon Mae. In 1928, Mickey Mouse, originally named Mortimer, was created.

In June 1947, Walt made a trip to Canada to visit his ancestral past. He stopped in at the Bluevale Post Office to enquire where the Disney homestead was located then drove to the farm that his father had spoken of so fondly. Walt drove on to Holmesville to visit the cemetery where his Disney great uncles and aunts, and his Richardson great grandparents are buried. Walt also visited Central School in Goderich and took some time to draw some cartoons for the students. He stayed the night in Goderich before travelling to Detroit and flying home.

Walt Disney died on December 15, 1966 at age 66 of lung cancer. His wife Lillian died September 16, 1997 at age 98.

Penhale Wagon

Huron County Disney connections also exist near the small village of Bayfield, Huron County. In 1974, as a hobby, Tom Penhale started building custom wagons. By 1983, it was a full time business. Tom’s business relationship with Disney started in December 1982 with the delivery of a set of hand crafted hames to the Walt Disney Ranch Fort Wilderness. In May 1983, he won the honour of building the show wagon that would compete in the 100th Anniversary of the Percheron Congress at the Calgary Stampede that coming June. He was chosen above many other craftsmen from all over North America.

Although a typical custom wagon would take about 3 months to complete, this one needed to be finished in 6 weeks. Official blueprints and a designer were flown in.

Working 16 hour days, with some local help, the wagon was completed on time. An artist came from the Disney World Studios in Florida to finish up. It was painted 4 different shades of blue, trimmed in 22 karat gold, and the lettering in silver spun with cotton.

Tom Penhale was given official recognition as the wagon builder when the Disney World Wagon was declared the World Champion Percheron Hitch during the 1983 Calgary Stampede.

Souvenir plate from the Goderich Township Sesquicentennial 1835 – 1985 featuring Tom Penhale’s Disney World wagon.

2018.0042.001

A Disney Parade

In July 1999, Goderich was the host for the first and only Canadian Hometown Disney Parade featuring Mickey Mouse, friends and characters. There were only 5 cities chosen in North America that year. Doug Fines, who was the President of the Goderich Chamber of Commerce at the time, submitted the winning essay to the contest to host the parade. The essay needed to convey true Mickey community spirit but of course having ancestral roots in Huron County helped as well. The organizers were expecting approximately 50,000 people to line the 2 ½ km route through Goderich. It is estimated that the final number was closer to 100,000.

While the connections between the famed Walt Disney and Huron County are few, their significance is no less meaningful. From ancestral roots to prize winning wagons and parades, it really is “a small world after all”.

by Sinead Cox | Mar 18, 2020 | Blog, Investigating Huron County History

Beth Knazook, Special Project Coordinator for Huron’s digitized newspaper project reviews the bitter rivalry between Huron’s first newspaper editors. You can search the newspapers yourself for free at https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers/

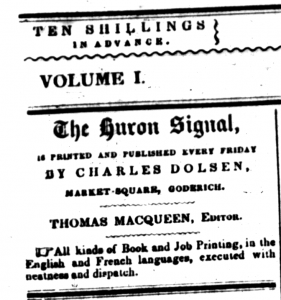

The Signal was the first newspaper printed in Huron County, beginning on February 4, 1848. Published in Goderich by Charles Dolsen, and edited by Thomas Macqueen (or “McQueen”), it promised to deliver “as many Essays and as much knowledge on all subjects of practical importance, as our space and time will reasonably allow,” Huron Signal (February 4, 1848), 2.

The Signal was the first newspaper printed in Huron County, beginning on February 4, 1848. Published in Goderich by Charles Dolsen, and edited by Thomas Macqueen (or “McQueen”), it promised to deliver “as many Essays and as much knowledge on all subjects of practical importance, as our space and time will reasonably allow,” Huron Signal (February 4, 1848), 2.

Macqueen was born in Ayrshire, Scotland, where he gained some fame as a poet and an accomplished lecturer. He immigrated to Canada and lived with his sister in Renfrew, Ontario, where he worked briefly as editor of The Bathurst Courier (Perth) before moving to Goderich to take up the position of editor for the Huron Signal. Instead of focusing only on local news, Macqueen brought literature, political, and cultural news from afar to the Western frontier of Canada. In its first issue, he ran articles detailing the history of Cortez’s conquest of Mexico, a travel account of Smyrna, and tales of “The Bushman” living in the Australian outback. He covered scientific news as well, re-printing snippets from other papers containing new information about exciting discoveries like electricity. He also included his own poetry, and encouraged others to contribute poems and songs.

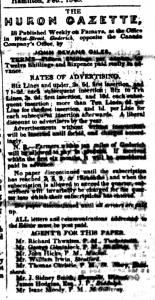

The Huron Gazette began publishing a few weeks later, on February 25, 1848, offering a conservative counterpoint to the Huron Signal’s liberal voice. There are fewer surviving copies of the Gazette from which to piece together the history and contents of the paper, but it seems to have been more practical in its aims. Local advertisements appeared alongside snippets of home and foreign news, dispatches from British Parliament, and editorials – with some entertaining fictional stories thrown in the mix. By late May, the paper had become so popular that editor John Beverley Giles considered either using larger paper sheets or going to a semi-weekly delivery to fit in more content. “We thank our kind supports for the patronage that has demanded from us this alteration, and we think it will evidence to the Province in general the enterprise and intelligence of the Huron Tract,” Huron Gazette (May 26, 1848), 2.

The Huron Gazette began publishing a few weeks later, on February 25, 1848, offering a conservative counterpoint to the Huron Signal’s liberal voice. There are fewer surviving copies of the Gazette from which to piece together the history and contents of the paper, but it seems to have been more practical in its aims. Local advertisements appeared alongside snippets of home and foreign news, dispatches from British Parliament, and editorials – with some entertaining fictional stories thrown in the mix. By late May, the paper had become so popular that editor John Beverley Giles considered either using larger paper sheets or going to a semi-weekly delivery to fit in more content. “We thank our kind supports for the patronage that has demanded from us this alteration, and we think it will evidence to the Province in general the enterprise and intelligence of the Huron Tract,” Huron Gazette (May 26, 1848), 2.

Perhaps a rivalry between the editors of these two papers was inevitable given their political leanings, but Mr. Giles appears to have had a particular talent for provoking the Signal’s Thomas Macqueen. His commentary in the Gazette frequently took the form of very personal attacks, which in turn provoked exasperated and increasingly angry responses in the Signal. Accusations made about the conduct of Mr. Macqueen on the occasion of the annual Agricultural Society’s Show in 1848 prompted several surprised and supportive letters to the editor condemning the malicious gossip in the Gazette.

Thomas Macqueen’s frustration with the Gazette seems to have reached its limit when he declared “We think Mr. Giles is unfortunate in every thing he takes in hand, and still more unfortunate when he tries the pen. His paper will soon be unable to contain his answers to the remonstrances of those he has offended by his impudence. We think he should give it up, —or if not, he should cease to be guided or counselled by those reckless inexperienced characters who are driving him to misery and disgrace for their own vain and selfish purposes, and who lately forced him to insult the respectable community of Goderich under the designation of ‘bare-footed boys and slip-shod girls,’” Huron Signal (May 12, 1849), 2.

Not many issues of the Huron Gazette have survived to explain Mr. Giles’ side of the story, but we do know that in June of 1849, Mr. Macqueen’s predictions about the Gazette’s impending doom were proven right. Mr. Giles abandoned the editorship of the Gazette, although the paper survived a little while longer under editor(s) who seem to have wanted to keep their names hidden. The Huron Signal reported at one point that “nobody is the Editor of it, and nobody will take the responsibility of it. It is not read by 50 men in the District of Huron, and of that fifty, there are not five who attach the slightest credit to any of its statements,” Huron Signal (June 22, 1849), 2. When the Gazette ceased publication in 1849, Mr. Giles left town – but not the newspaper business. He would take up the editorship of the St. Catharines Constitutional, hopefully with better results.

Inkwell used by Thomas McQueen. 1978.10.1. Collection of the Huron County Museum.

Macqueen edited the Signal until his death in 1861 at the age of 57, at which point J.W. Miller took over as editor while the publishing side was managed by Macqueen’s son-in-law, T. J. Moorhouse. The paper was then sold to William T. Cox, who ran it until 1870, and from there it changed hands many more times over the years. The Huron Signal survives today in the form of the Goderich Signal Star. Over the course of the paper’s long history, there has been a lot more (friendly) competition in the Huron County weekly news business.

by Sinead Cox | Nov 11, 2017 | Exhibits, Investigating Huron County History

From Nov. 21st, 2017 to March 2018, the museum’s temporary Hot off the Press: Seen in the County Papers exhibit will look behind the headlines to the men, women and changing technologies that have brought Huron’s weekly papers to press for over almost 175 years. In this Remembrance Day post, Sinead Cox, Curator of Engagement & Dialogue and curator of the upcoming exhibit, examines the life of one Huron newsman who was also a veteran of the First World War, and follows the story of his return from service via mentions in the local weekly papers.

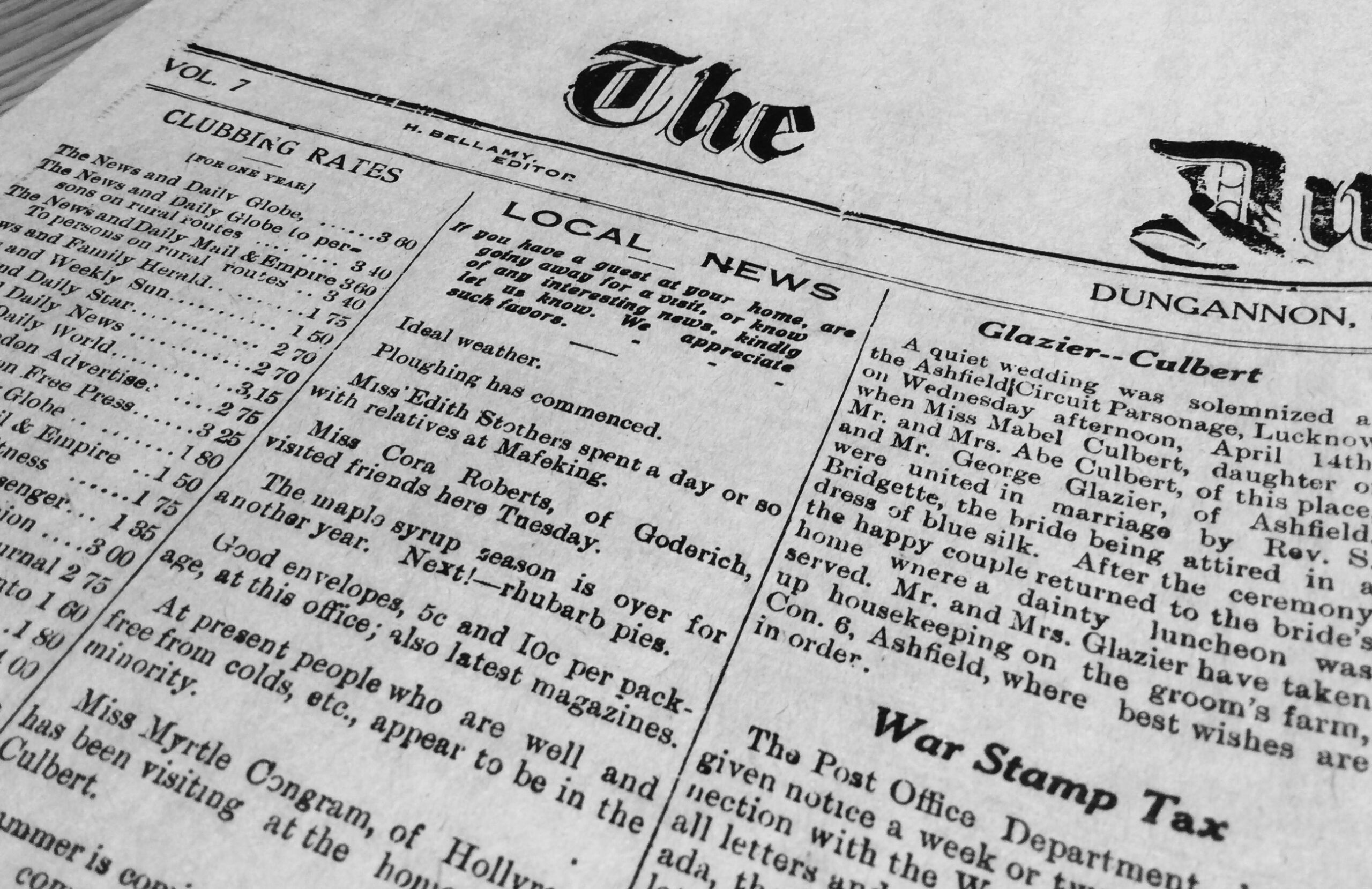

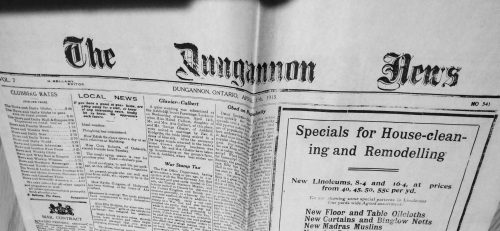

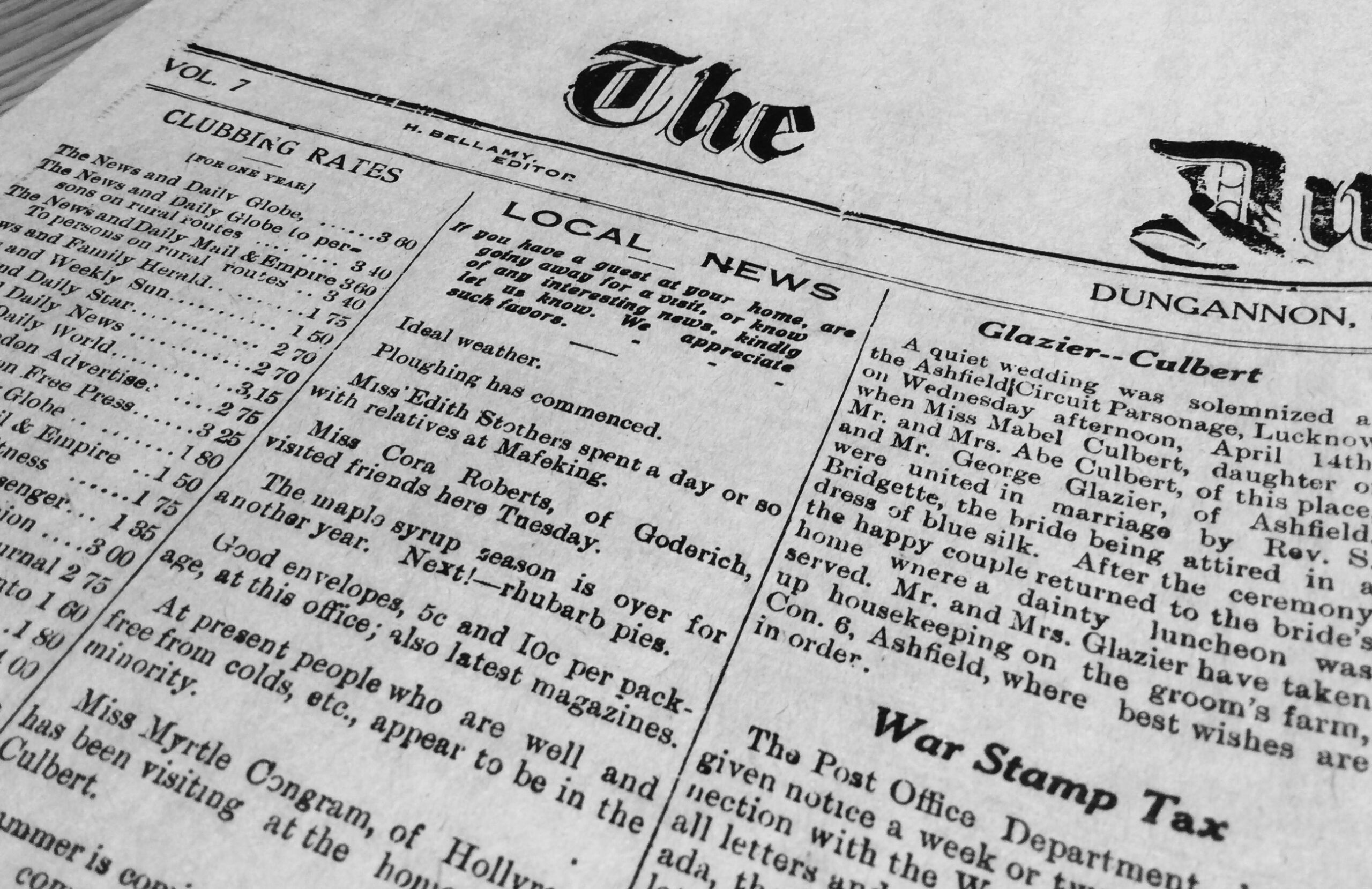

The Dungannon News, 1915-04-15

From my research into Huron County’s newspapers, it’s clear that a lot of effort, long hours and personal sacrifice often went into putting a paper to press and ensuring the latest edition reached local subscribers’ doorsteps on time. There were few excuses that could justify a late paper on the part of its proprietors: perhaps broken equipment, the precedence of a contracted print job (ie printing election ballots), adverse weather, public holidays, or even the rare editor’s vacation. One of the most notable reasons to stop the presses, however, occurred in 1916 when The Dungannon News ceased publication entirely because its editor enlisted to serve overseas with Huron’s 161st Battalion.

Pte. Bellamy’s attestation paper. You can access his full personnel file at: http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/

Born in 1891 in Blanshard Township, Perth County, Charles Arthur Harold “Harry” Bellamy had moved to Huron by 1908 when his step-father, Leslie S. Palmer–a former staffer at the St. Marys Journal and owner of the Wroxeter Star–founded The Dungannon News. His sisters, Amelia and Luella Bellamy, also worked locally as operators for the Dungannon telephone office. When his mother and step-father moved to Goderich in 1914, Harry became both editor and publisher of the News while still in his early twenties.

As editor, H. Bellamy strongly supported Canada’s involvement in the Great War within the pages of his publication, and by March of 1916 had decided to enlist himself. At only 24 years old, and a newlywed of less than two years with his wife, Annie Pentland of Ashfield Township, Editor Bellamy signed up to serve with the Canadian Expeditionary Forces at Goderich. With the departure of its proprietor, The Dungannon News merged with Goderich’s Tory weekly, The Star, and the newsman became the news as fellow editors praised Harry Bellamy’s decision in the columns of their papers.

The Wingham Advance, 1916-03-23, pg 5

Assigned to the 58th Battalion in Europe, Pte. Bellamy appeared once again in the pages of the local weeklies through his letters from the front. Stationed “somewhere in France” on Dec. 26th, 1916, Harry wrote to his friend F. Ross of how his “three or four days’ trench life” had begun with digging out a trench collapsed by shell-fire; he had become accustomed to ducking down for enemy fire “no matter how deep the mud and water is.” While evading sniper bullets in a no man’s land crater, Bellamy says he pretended he was at home, practicing with friends at the Dungannon Rifle Association.

The Wingham Times, 1911-12-28, pg 4

Imagining away the conditions he described would have no doubt been difficult: “We sleep and rest in the dugouts, which are twenty to twenty-five feet underground. After splashing, crawling and wading through trench mud for hours at a time, we find it quite a relief to get down in these underground quarters.” On Christmas day he witnessed “a fierce bombardment…It was a magnificent sight to see the green and red flames and the shells with their tails of fire flying…The noise and din of the various kinds of explosives in use was deafening.” In the same letter, which Goderich’s The Signal printed on its front page, he claimed that the brutal lifestyle had not dampened the soldiers’ spirits: “we never worry over here. We content ourselves with singing, ‘Pack all your troubles in your old kit bag and smile, smile, smile.’”

Although he was writing for the local papers, Pte. Bellamy was not able to regularly read them in Europe, and complained that the delays in mail also prevented him from keeping up-to-date with happenings in Huron County. According to his service records, a year after he had enlisted at Goderich, Harry fell ill with trench fever–an infectious disease carried by body lice. He left France for treatment in the U.K., and after complaining of pain in his limbs at York County Hospital, doctors at the King’s Red Cross Canadian Convalescent diagnosed him with myalgia (joint pain) and an abnormally fast pulse.

The Huron Expositor, 1917-10-12, pg 5

In articles subsequently written for the Goderich Star, Pte. Bellamy did not detail his failing health, instead returning to his pen to share his experiences sightseeing on leave in Scotland and Ireland in August, 1917. Ever a committed imperialist, he enjoyed witnessing the Glorious Twelfth celebrations in Belfast, but reported caring less for his time in southern Ireland, since “there is no love lost between those in khaki and the Irish rebels.” He felt wistfulness upon the end of his holiday, but Pte. Bellamy’s belief in the righteousness of the war had not wavered; he used his Star articles to rally homefront sentiments against peace until the enemy could be decisively defeated: “let…every one of us, as Canadians, recapture the heroic mood in which we entered the war.”

The Signal, 1917-12-06, pg 6

Unable to resume his duties as a soldier, Pte. Bellamy returned to Canada, where in addition to his persistent trench fever, he received a diagnosis of neurasthenia–a contemporary term broadly used for nervous disorders. After his homecoming, he reappeared frequently in the local news columns, usually receiving mention for promoting the war effort at local patriotic events or canvassing for Victory Loans.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

In April 1918, a medical board at Guelph honourably discharged Harry as medically unfit due to illness contracted on active service. His records list a ‘nervous debility,’ as well as trench fever as the causes for his dismissal, and note that “this man would not be able to do more than one quarter of a days [sic] work.” The listed symptoms in his medical records include dizzy spells, light headedness, restlessness, hand tremors, headaches, and an irregular heartbeat. The Board determined that the probable duration of his debility was “impossible to state.”

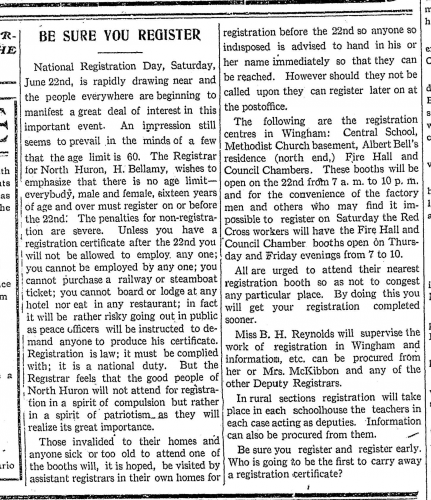

The Wingham Advance, 1918-06-13, pg 5

Despite experts’ doubts about his ability to cope with a full-time job, Harry received a temporary government position as North Huron’s Registrar for 1918’s National Registration Day effort. The federal government intended this wartime “man and woman power census” to identify available labour forces for the homefront and overseas by requiring all Canadians over sixteen to register.

Nothing in the newspapers suggests that Harry Bellamy returned to printing or publishing on a full-time basis in Dungannon. After the war was over in 1919, Ashfield accepted Harry’s application for the township’s annual printing contract with special consideration to him as a “returned soldier,” but according to an item in The Wingham Advance he later declined the work for the pay offered. There was evidently a vocation that Harry Bellamy now felt more passionately for than journalism, because in May of that year the New Era records that he moved to Toronto to accept a bureaucratic position “in connection with the re-establishment of soldiers.” In 1921, Harry ultimately sold The Dungannon News printing equipment to a buyer from Meaford, and he and wife Annie settled permanently in Toronto.They didn’t entirely disappear from print, however, as local news columns over the next decade continued to note the couple’s visits to friends and family in Huron County.

The Signal, 1921-3-31, pg 4

Following Pte. Bellamy’s story via short items in the county papers certainly does not provide a full picture of his life, nor the toll of his experiences in the trenches of France. The information gleaned, though, does speak to the value of these local weeklies as historical resources, and that comparing them against other records–in this case Pte. Bellamy’s military personnel files– can help us to read between the lines. It’s also a pertinent reminder that both historical and news sources are better understood if we know a little about the context and perspective of the people creating them. What emerged in this case was the story of a man whose politics on the page never changed, whose service to the Canadian government continued beyond the battlefield and loyalty to the British empire never faltered, but who nevertheless could not quite pack the personal consequences of war away in an “old kit bag and smile, smile, smile.”

Hot off the Press: Seen in the County Papers opens Nov. 21st at the Huron County Museum! Visit the exhibit to learn more about the stories behind Huron’s historic headlines. You can browse the newspaper collection from the comfort of home at dev.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers. Information for this blog post came from Huron County’s digitized newspapers and Library and Archives Canada’s digitized service records.

by Sinead Cox | Nov 6, 2017 | For Teachers and Students, Investigating Huron County History

What is now Huron County includes parts of the traditional territories of multiple Anishinaabe communities. Liz Duern is a current University Student, and worked as a Museum Assistant at the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol during the summer of 2017. In this guest blog post for Treaties Recognition Week, Liz shares what she learned during her initial research into the treaty history of this area.

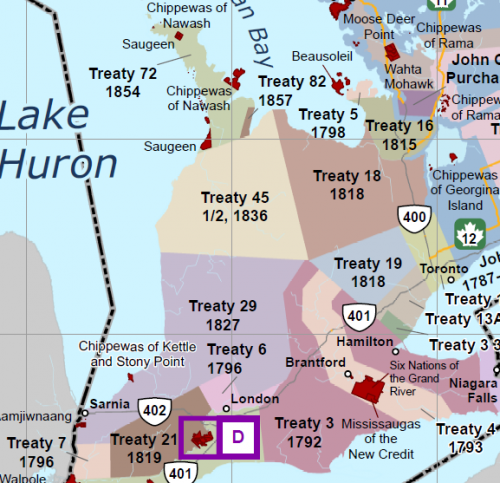

What is a Treaty? How were they created? Treaties are agreements between First Nations and the British Crown. While the Crown used treaties to gain access to land for settlement and mining, First Nations understood treaties as building nation-to-nation relationships and protecting their continued stewardship of the land. The Crown often promised to protect First Nations’ rights and to set aside tracts of land for the exclusive use of the First Nations and their members. Today, the elders of many indigenous communities hold a great amount of knowledge regarding the intent of the treaties passed down through oral history.

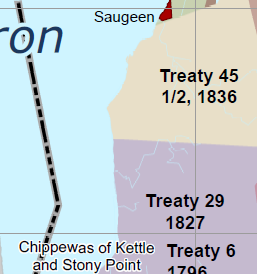

Detail from https://files.ontario.ca/firstnationsandtreaties.pdf

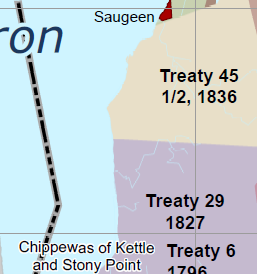

Treaty 29: Following earlier provisional agreements, the Huron Tract (1827) The Huron Tract Treaty was signed by eighteen Anishinaabek chiefs in 1827 in Amherstburg; in addition to what is now Lambton County and part of Wellington under settler municipal boundaries, the Huron Tract included most of what would become the Huron District-most of Huron County and parts of Perth & Middlesex. This treaty ceded 99% of the communities’ remaining lands to the British Crown, and designated four reserves: one along the south of St. Clair Township, one at Sarnia, and two on Lake Huron (Kettle and Stony Point).

Treaty 45 ½: The Saugeen Treaty (1836) Treaty 45 ½, signed on August 9, 1836, dealt with part of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation’s traditional territory. The British promised the Saugeen Ojibway Nation that they would protect the Indigenous peoples who resided on the Saugeen Peninsula and that the Saugeen Peninsula would be protected for their use. Not long after this, the British claimed that the Saugeen Peninsula could not be protected against settlers unless another treaty was negotiated. This treaty was Treaty 72, which ceded about 500,000 acres of the Saugeen Peninsula to the British Crown.

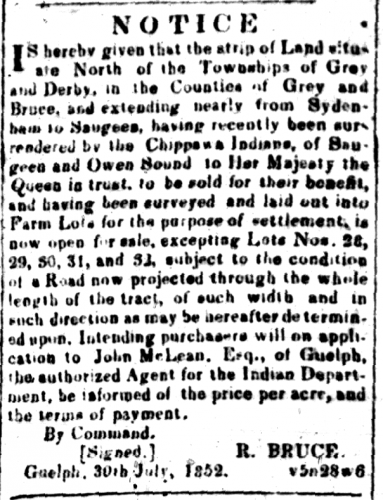

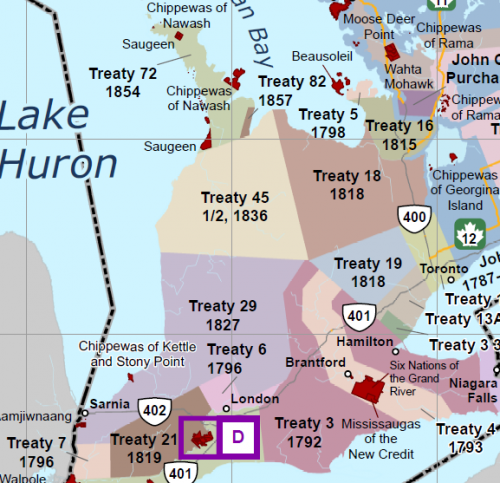

Huron Signal, 1852-09-16, page 4

via https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers/

Treaties are not just historical documents, but outline ongoing rights and responsibilities that are protected by the Constitution Act, 1982. These rights and the spirit of the original agreements have often been violated “by colonial policies designed to exploit, assimilate and eradicate” First Nations communities and their cultures. Access teaching resources to better understand what it means to live on Treaty Land.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.