by Sinead Cox | Jan 25, 2022 | Archives, Exhibits, Image highlights

The Huron County Museum’s temporary exhibit Forgotten: People and Portraits of the County features unidentified portraits captured by Huron County photographers. In addition to the onsite exhibit, photos are shared in an online exhibit and Facebook group in hopes that some of these ‘Forgotten’ faces will remembered and named. Curator of Engagement & Dialogue Sinead Cox shares highlights of the exhibit’s remembering efforts so far.

Semi-Weekly Signal, (Goderich) 07-27-1869 pg 2

The Huron County Museum has an incredible collection of photographs in its Archives – especially studio portraits from commercial photographers within Huron County (spanning the county from Senior Studio in Exeter, Zurbrigg in Wingham, and everywhere in between). Not all of these photographs came with identifying information for their subjects, or even known donors or photographers. The Forgotten exhibit has provided an opportunity to delve deeper into the clues that can be present in everything from associated family trees to fashion styles, photographer’s marks, and photography methods that can provide more context, narrow timelines, or even lead to the re-discovery of names. I am especially grateful for the enthusiastic participation we have already had from photo detectives from the public who have contributed to remembering Huron County’s ‘Forgotten’ faces. Hopefully this is just the beginning of adding value to our collection.

Professional studio photographs were often (and still are!) sent as gifts to family and friends. Local photographers saved negatives to sell reprints at a later date, and these negatives were also sometimes inherited when a studio changed hands. It’s very possible your own family photo collection contains the duplicate of a photo that exists in the possession of an archive or a distant relation somewhere else in the world. Finding matches between the faces in those photos is one way to solve photographic mysteries, and why a shared space to upload and comment on photos, like the Forgotten Facebook group, has the potential to put names to faces even after more than a century has passed since the camera flash!

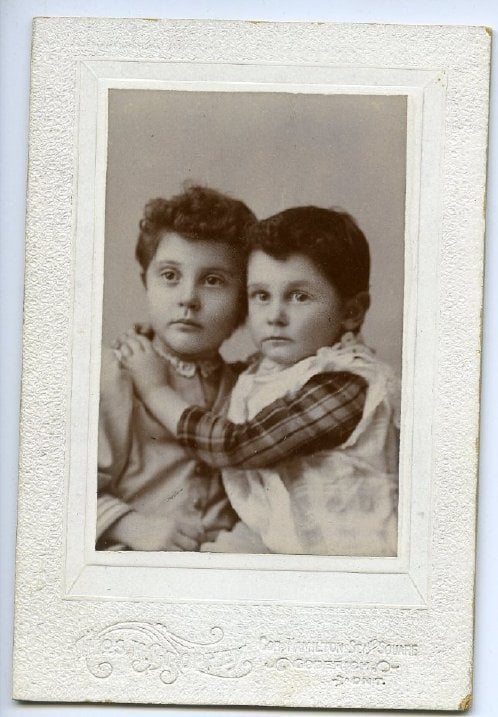

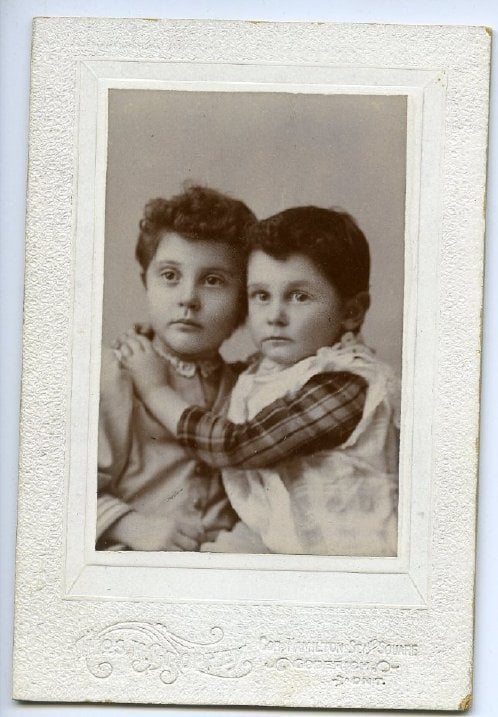

2011.0013.020. Photograph

2017.0013.011. Glass negative

During preparation for the exhibit, staff recognized that a photograph and a glass negative from unrelated donations depicted the same image of a pair of children (their nervous expressions at having their photo taken were difficult to miss). The photo and negative came to the museum from different donors, six years apart. Information provided with the donation of the photograph indicates that these children may be related to the McCarthy and Hussey families of Ashfield Twp and Goderich area; the studio mark for Thos. H. Brophey is also visible on its cardboard mount, dating the image approximately between 1896 and 1904. The matching negative came from a collection related to Edward Norman Lewis, barrister, judge and MP from Goderich. The shared connection between the donations provides one more clue to help identify the unnamed children, and gives the negative meaning and value (through a place, time and potential family connection) it didn’t previously have without the photograph’s added context. You can see both the photograph and the negative on display in the temporary Forgotten exhibit, which is on at the Museum until fall 2022.

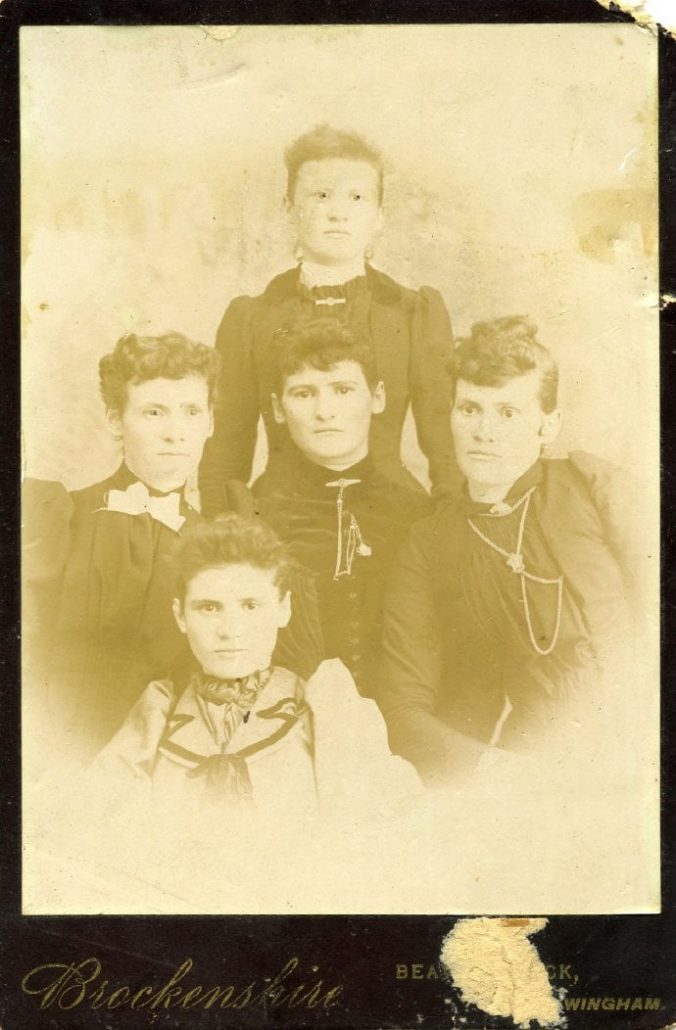

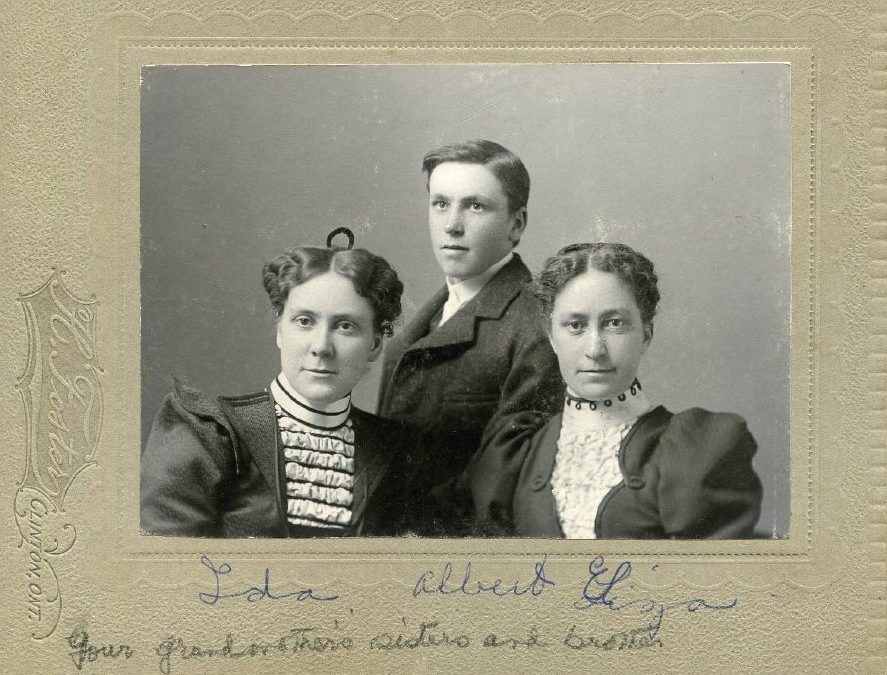

2021.0053.006. The “Garniss sisters”: Sarah Ann, Elizabeth, Eliza Maria Ida, Jemima, Mary Lillian. Can you help us identify which sister is which?

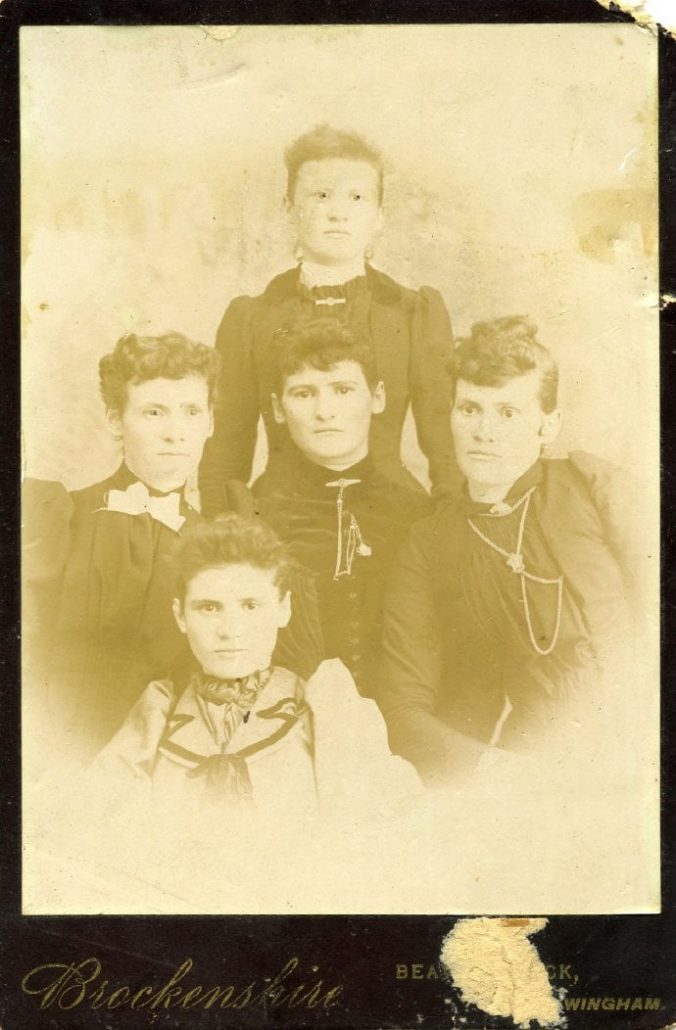

Sometimes photographs arrive to the collection with partial identifications or known connections to a certain family, even when individual names are missing. In those cases, knowledge of family histories can help pinpoint who’s who. Members of the Facebook group were recently able to name all five Morris Township women identified as only the “Garniss sisters” on the back of a photo from Brockenshire Studio, Wingham.

A996.001.095

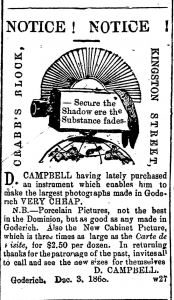

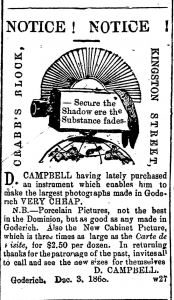

Patterns tend to emerge with access to larger collections from the same location or time period. Although studio photographers later in the 19th century prided themselves on offering a large selection of backdrops, photos from local studios in the 1860s and 1870s often show a more simple set-up. In posting the ‘Forgotten’ photos online, I noticed that the studio space of Goderich photographer D. Campbell can be recognized by the consistent presence of a striped curtain in the background (and more often than not the same tassel-adorned chair) and a distinctive pattern on the floor, as seen in both the photos above and below. This helped identify additional photographs as Campbell’s work, and therefore place them in Goderich circa 1866-1870 , even when a photographer’s mark or name was absent from they physical photo.

A996.001.071. This photograph is labelled as “the Miss Henrys.” Do you have any information that might reveal their first names?

Crowdsourcing information through the online exhibit and group has allowed fresh pairs of eyes to notice detail previously missed in some of the museum’s photos, even when the evidence was captured by the staff doing the scanning and cataloguing work. In November, the Facebook group spotlighted unidentified soldiers, and one of the members pointed out a photographer’s mark embossed on the bottom right corner of a group photo. Staff were able to look at the original photo to get a clearer look to confirm the studio was identified as “G. West & Sons, Godalming.” Godalming is a town in Surrey, England near Witley Commons, which hosted many Canadian soldiers during the First and Second World Wars.

2004.0044.005. Photographer: G. West & Sons, Godalming, Surrey, U.K.

A950.1740.001

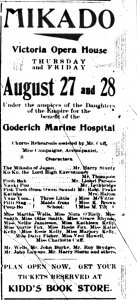

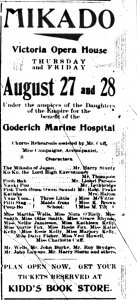

The Signal 08-27-1903 pg 8.

Comparing photographs with other readily available local historical resources like Huron’s digitized newspapers can also help provide new insight. Partial identifications on a group photo of young women in theatrical costumes without a location allowed a group member to link it to a 1903 Goderich production of Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Mikado. Further research in the newspapers provided a full list of the names of the participating cast and more information about the production, which toured Huron County. This information is now attached to the photograph’s catalogue record to benefit future researchers.

Although many historical photos may be ‘Forgotten’, if they are preserved and housed they are not lost. They still retain the potential for remembering , and to be re-connected to descendants and communities through extant clues and the growing possibilities of digitization and online sharing. For more highlights from the exhibit and tips for identifying mystery subjects photos or caring for your own collections, join is Feb. 9, 2022 for the second webinar in our exhibit series: Forgotten in the Archives.

If you can help identify a ‘Forgotten’ face, email us at museum@huroncounty.ca!

For more on the Forgotten: People & Portraits of the County exhibit and related coming events:

by Amy Zoethout | Feb 10, 2021 | Archives, Blog

Mary Frances Griffin, 1914. Photo provided by David Hammer.

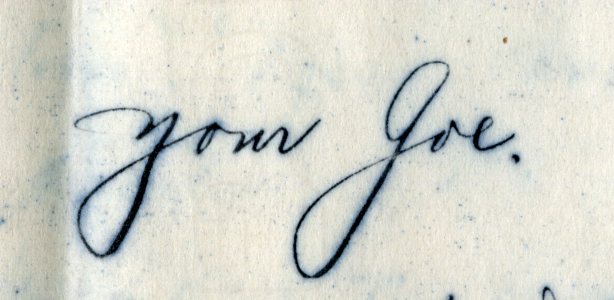

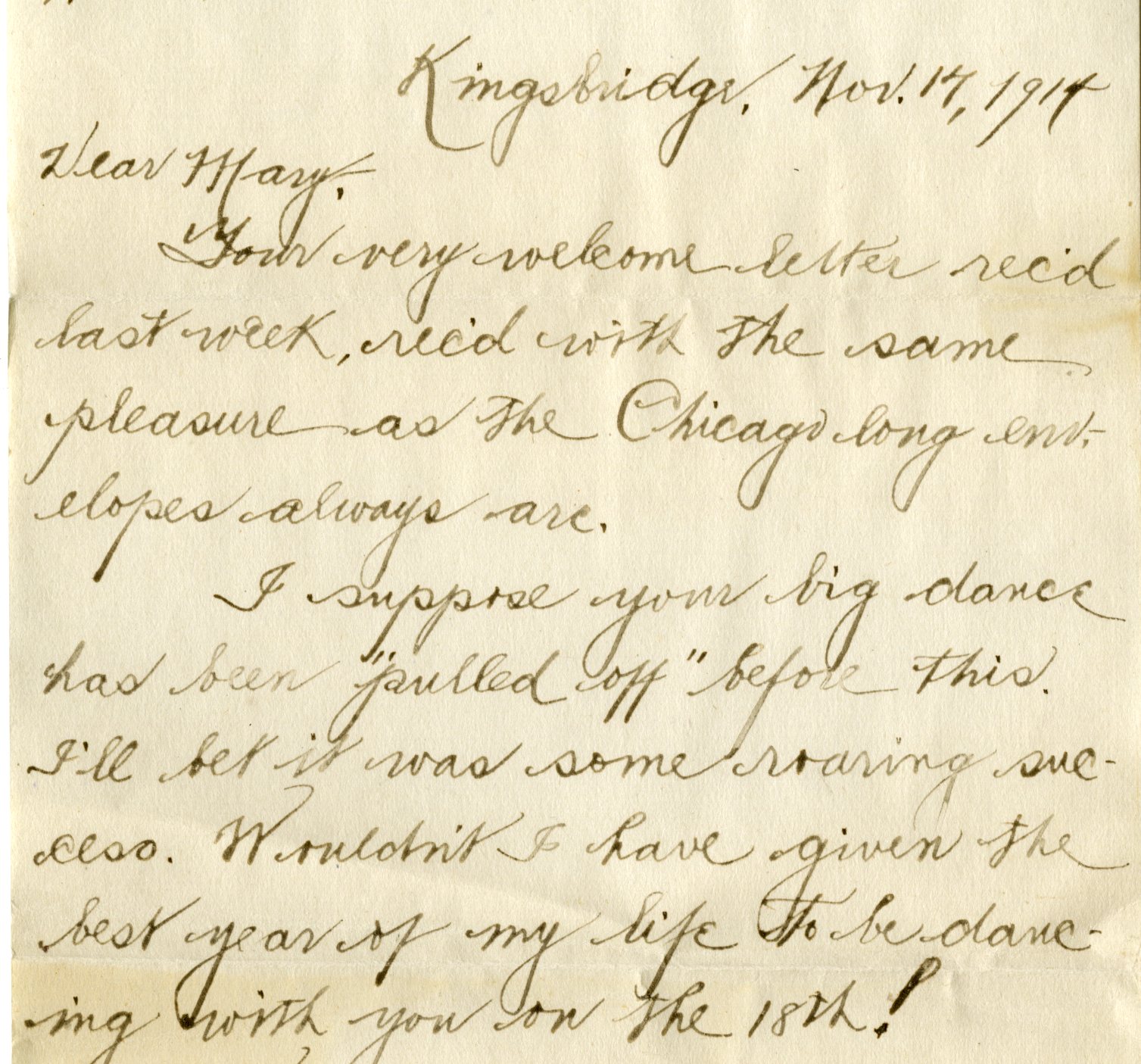

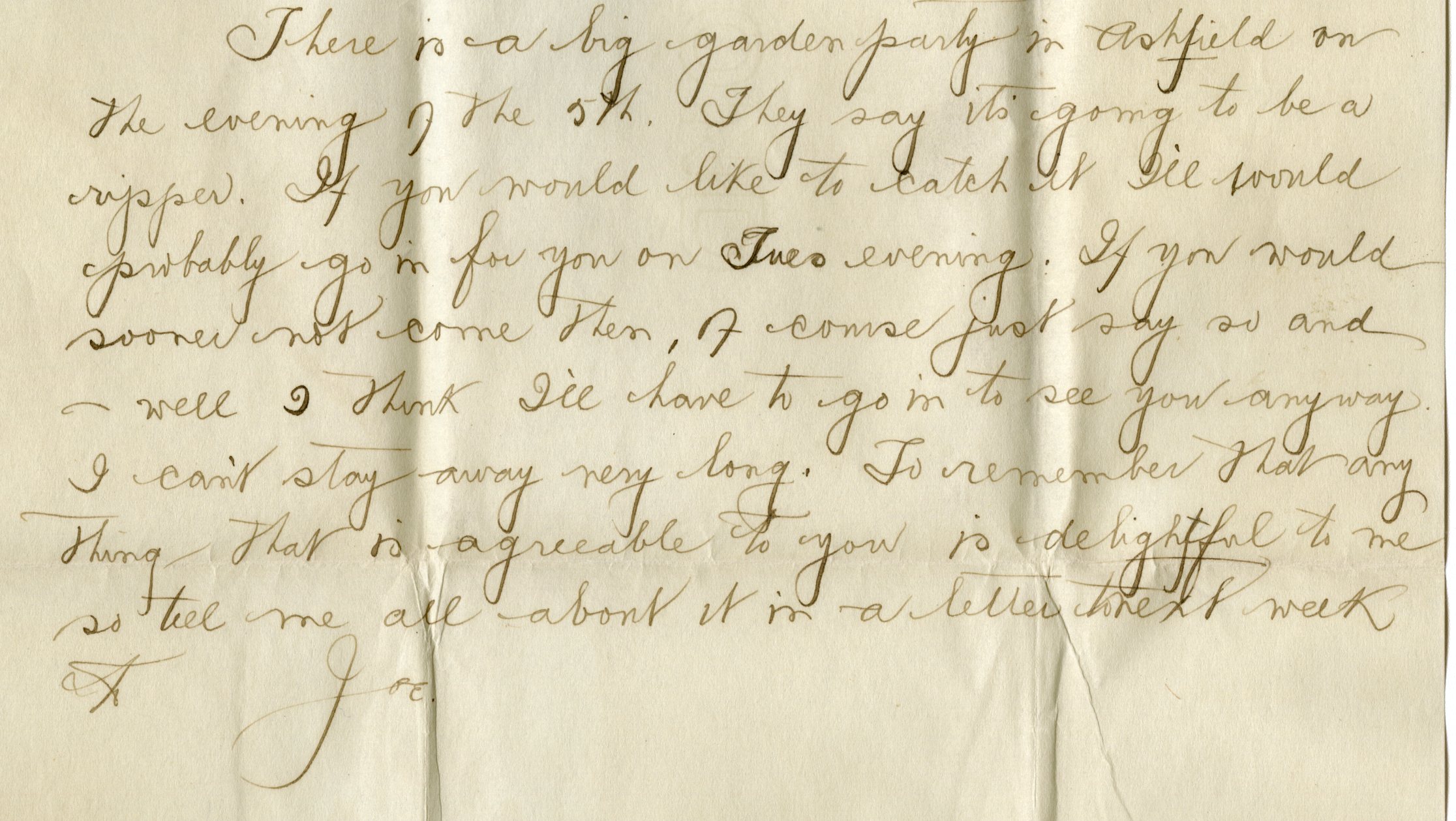

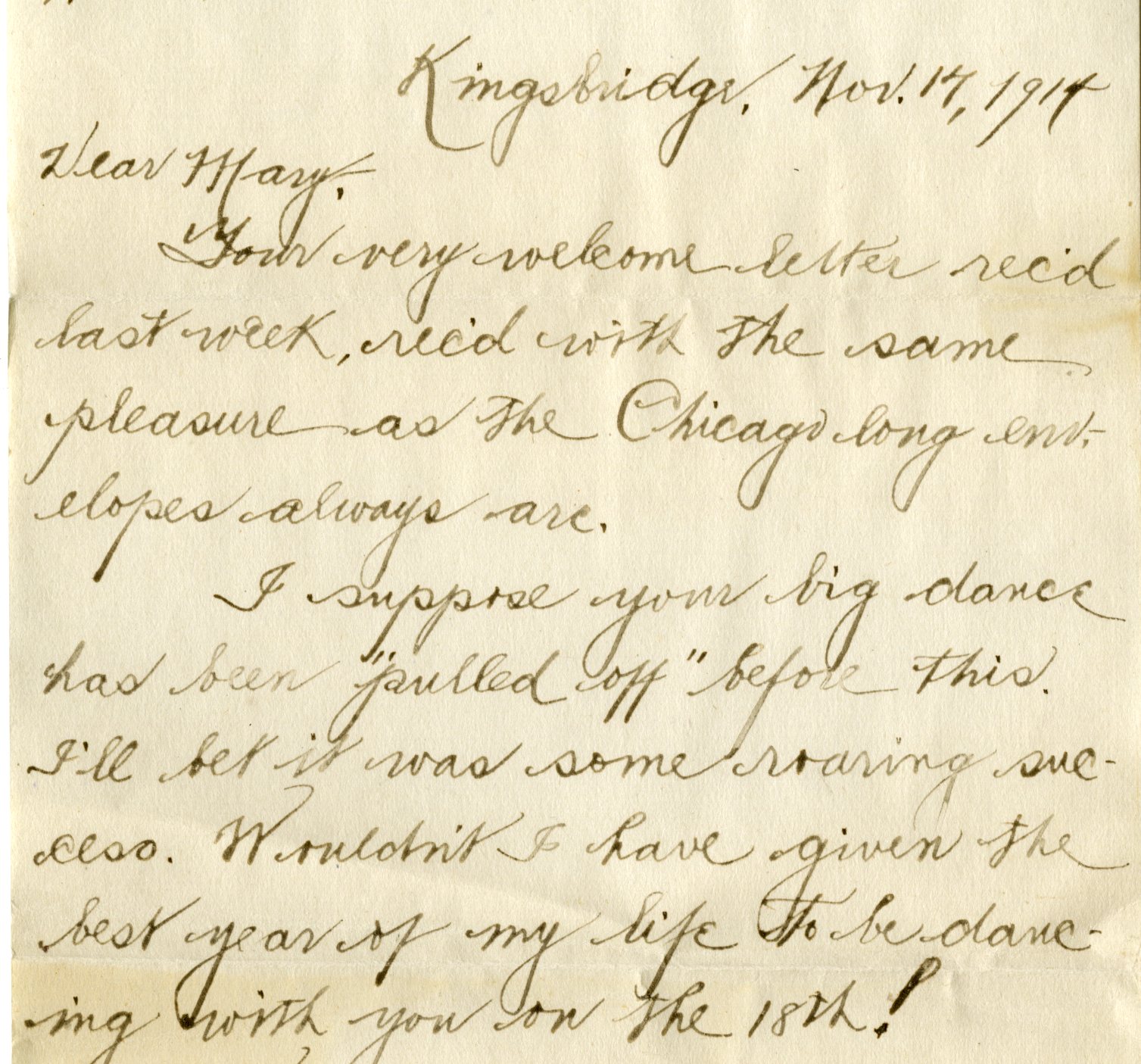

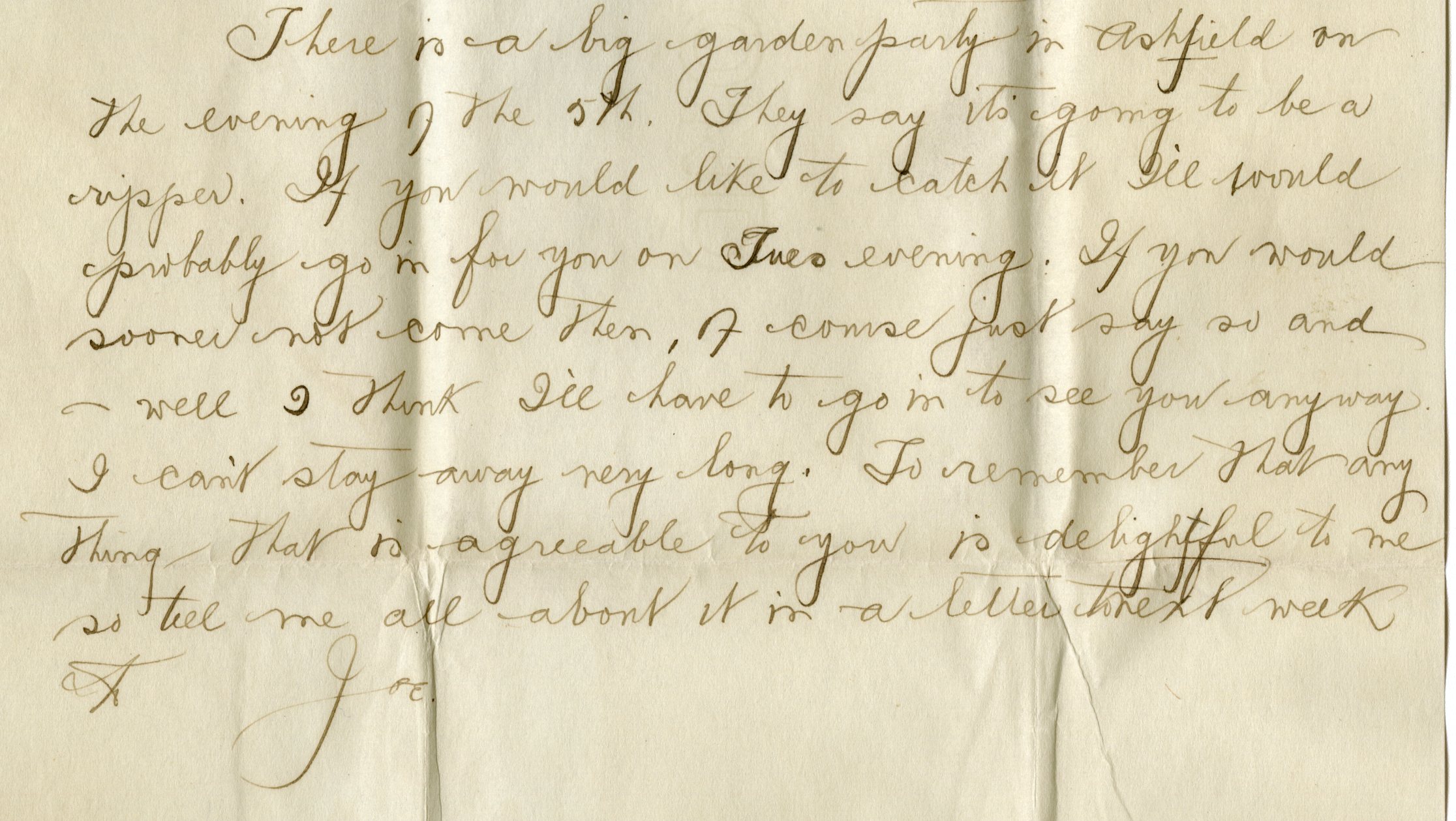

In the spirit of Valentine’s Day, the Huron County Museum shares a few images showing excerpts from letters recently donated to the Huron County Archives. The letters beautifully speak to life in rural Huron County in the early 1900s and share a glimpse into young love.

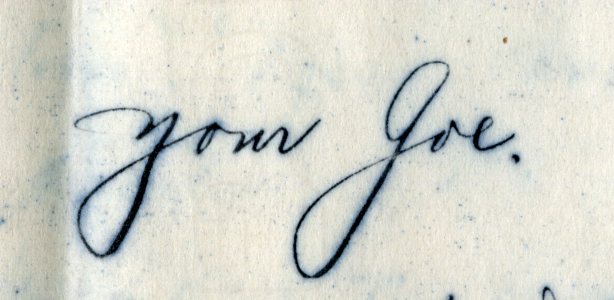

Sixteen letters in total were donated to the Museum’s archival collection, all written by a young Ashfield Township man named Joe during the years of 1913 through 1917 to Mary Frances Griffin. The correspondence between Joe and Mary took place after she had moved to Chicago after a time spent living in the Kingsbridge area. The letters were eventually passed down to her grandson, David Hammer, of Palatine, Illinois, who kindly donated them to the Museum.

In donating the letters, David wrote the following about his grandmother: “When Mary’s father, Timothy Griffin, died in Marquette, Michigan, Mary was sent to live with her aunts and uncles in Kingsbridge [Huron County]. She lived there from 1910 to 1912 and in the following years returned many times during the summer. Sundays she went to church. Weekdays she did chores, working in the garden, helping with cooking and cleaning. On Saturday nights the big excitement was to go dancing with friends and come home late. And always the question: Who was getting serious with whom? The possibilities were endless!”

by Sinead Cox | Nov 11, 2017 | Exhibits, Investigating Huron County History

From Nov. 21st, 2017 to March 2018, the museum’s temporary Hot off the Press: Seen in the County Papers exhibit will look behind the headlines to the men, women and changing technologies that have brought Huron’s weekly papers to press for over almost 175 years. In this Remembrance Day post, Sinead Cox, Curator of Engagement & Dialogue and curator of the upcoming exhibit, examines the life of one Huron newsman who was also a veteran of the First World War, and follows the story of his return from service via mentions in the local weekly papers.

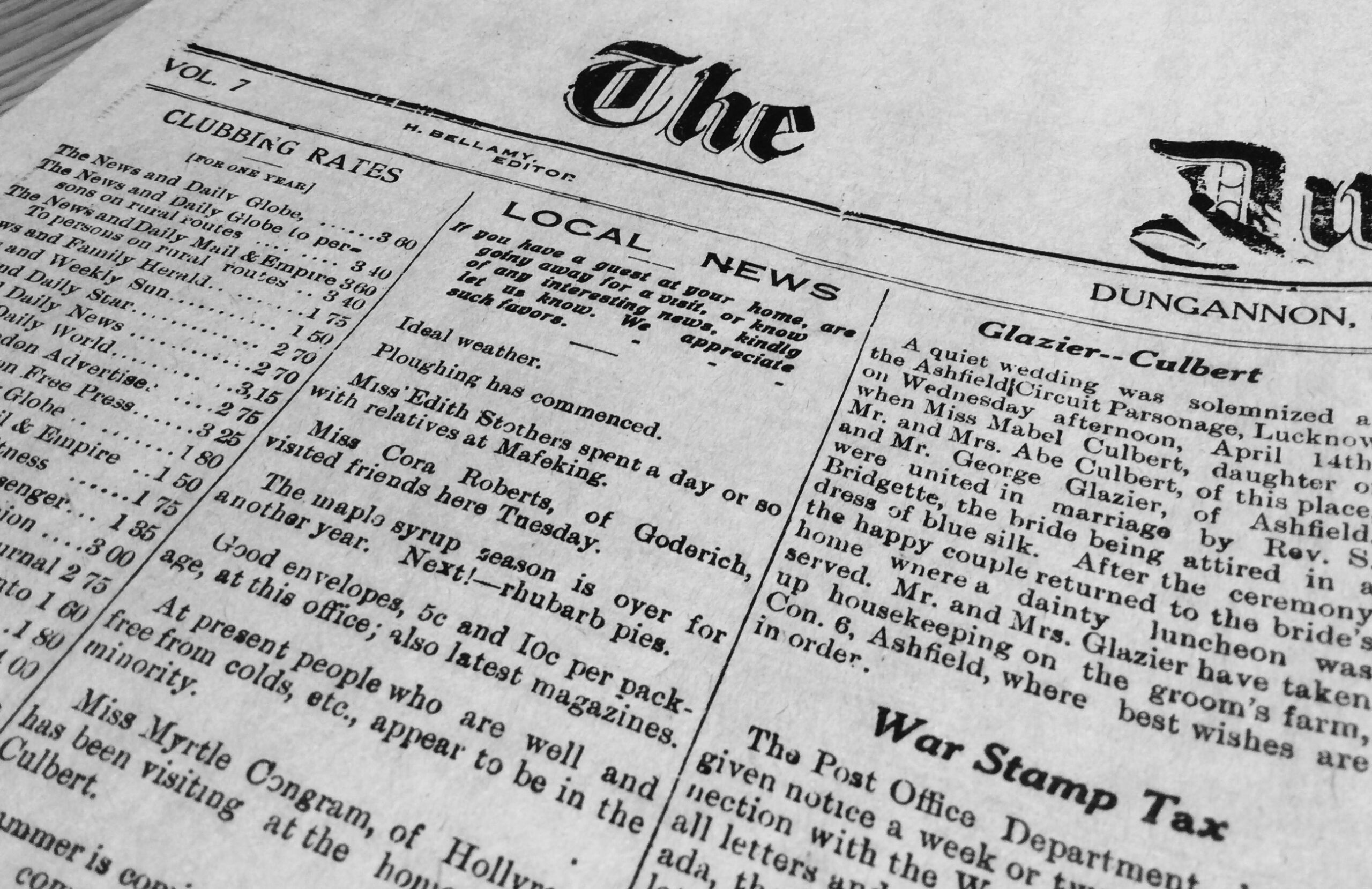

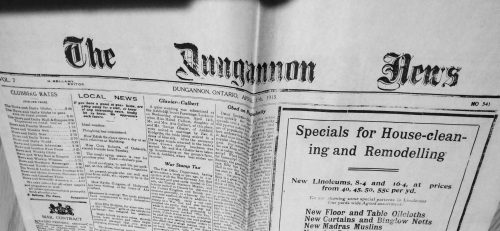

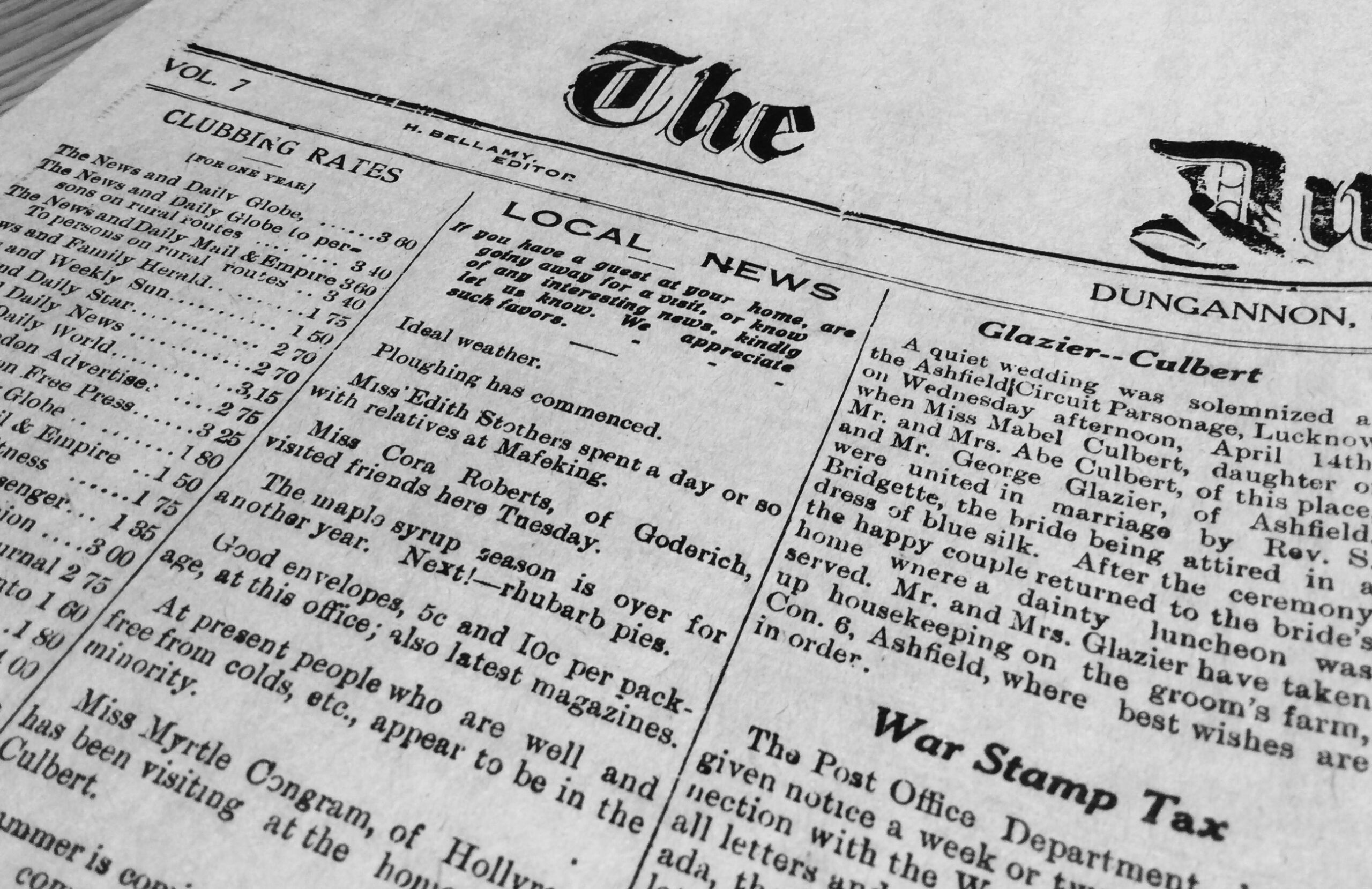

The Dungannon News, 1915-04-15

From my research into Huron County’s newspapers, it’s clear that a lot of effort, long hours and personal sacrifice often went into putting a paper to press and ensuring the latest edition reached local subscribers’ doorsteps on time. There were few excuses that could justify a late paper on the part of its proprietors: perhaps broken equipment, the precedence of a contracted print job (ie printing election ballots), adverse weather, public holidays, or even the rare editor’s vacation. One of the most notable reasons to stop the presses, however, occurred in 1916 when The Dungannon News ceased publication entirely because its editor enlisted to serve overseas with Huron’s 161st Battalion.

Pte. Bellamy’s attestation paper. You can access his full personnel file at: http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/

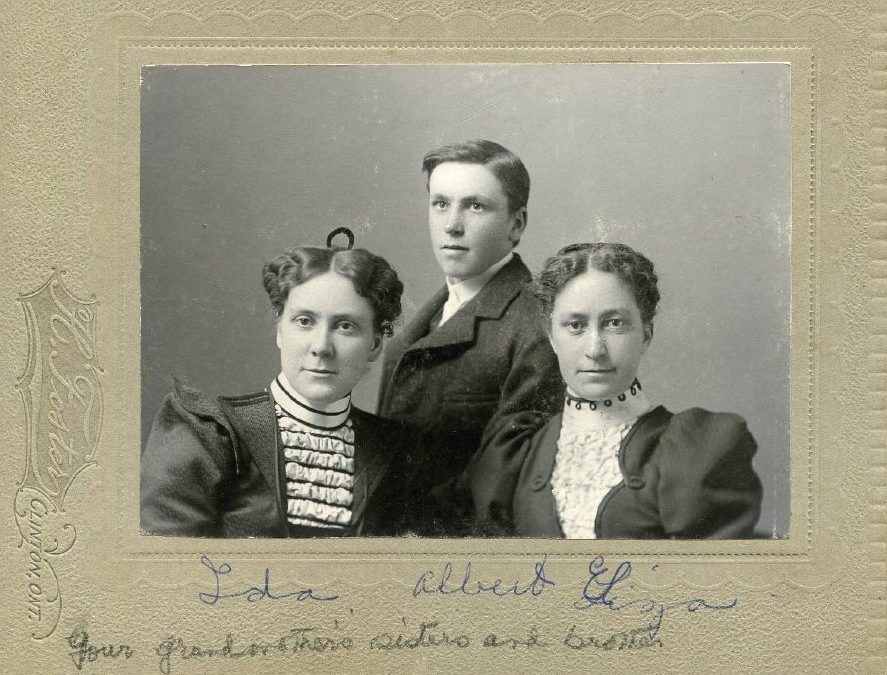

Born in 1891 in Blanshard Township, Perth County, Charles Arthur Harold “Harry” Bellamy had moved to Huron by 1908 when his step-father, Leslie S. Palmer–a former staffer at the St. Marys Journal and owner of the Wroxeter Star–founded The Dungannon News. His sisters, Amelia and Luella Bellamy, also worked locally as operators for the Dungannon telephone office. When his mother and step-father moved to Goderich in 1914, Harry became both editor and publisher of the News while still in his early twenties.

As editor, H. Bellamy strongly supported Canada’s involvement in the Great War within the pages of his publication, and by March of 1916 had decided to enlist himself. At only 24 years old, and a newlywed of less than two years with his wife, Annie Pentland of Ashfield Township, Editor Bellamy signed up to serve with the Canadian Expeditionary Forces at Goderich. With the departure of its proprietor, The Dungannon News merged with Goderich’s Tory weekly, The Star, and the newsman became the news as fellow editors praised Harry Bellamy’s decision in the columns of their papers.

The Wingham Advance, 1916-03-23, pg 5

Assigned to the 58th Battalion in Europe, Pte. Bellamy appeared once again in the pages of the local weeklies through his letters from the front. Stationed “somewhere in France” on Dec. 26th, 1916, Harry wrote to his friend F. Ross of how his “three or four days’ trench life” had begun with digging out a trench collapsed by shell-fire; he had become accustomed to ducking down for enemy fire “no matter how deep the mud and water is.” While evading sniper bullets in a no man’s land crater, Bellamy says he pretended he was at home, practicing with friends at the Dungannon Rifle Association.

The Wingham Times, 1911-12-28, pg 4

Imagining away the conditions he described would have no doubt been difficult: “We sleep and rest in the dugouts, which are twenty to twenty-five feet underground. After splashing, crawling and wading through trench mud for hours at a time, we find it quite a relief to get down in these underground quarters.” On Christmas day he witnessed “a fierce bombardment…It was a magnificent sight to see the green and red flames and the shells with their tails of fire flying…The noise and din of the various kinds of explosives in use was deafening.” In the same letter, which Goderich’s The Signal printed on its front page, he claimed that the brutal lifestyle had not dampened the soldiers’ spirits: “we never worry over here. We content ourselves with singing, ‘Pack all your troubles in your old kit bag and smile, smile, smile.’”

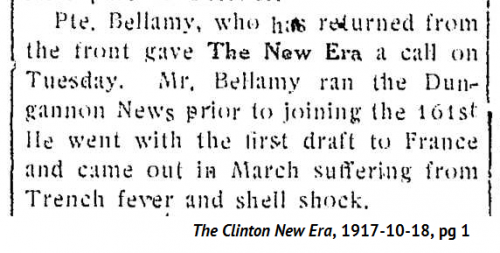

Although he was writing for the local papers, Pte. Bellamy was not able to regularly read them in Europe, and complained that the delays in mail also prevented him from keeping up-to-date with happenings in Huron County. According to his service records, a year after he had enlisted at Goderich, Harry fell ill with trench fever–an infectious disease carried by body lice. He left France for treatment in the U.K., and after complaining of pain in his limbs at York County Hospital, doctors at the King’s Red Cross Canadian Convalescent diagnosed him with myalgia (joint pain) and an abnormally fast pulse.

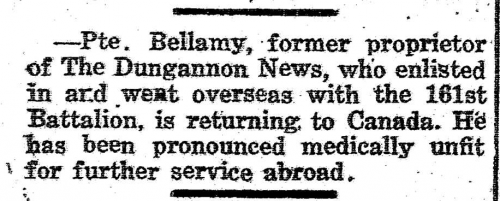

The Huron Expositor, 1917-10-12, pg 5

In articles subsequently written for the Goderich Star, Pte. Bellamy did not detail his failing health, instead returning to his pen to share his experiences sightseeing on leave in Scotland and Ireland in August, 1917. Ever a committed imperialist, he enjoyed witnessing the Glorious Twelfth celebrations in Belfast, but reported caring less for his time in southern Ireland, since “there is no love lost between those in khaki and the Irish rebels.” He felt wistfulness upon the end of his holiday, but Pte. Bellamy’s belief in the righteousness of the war had not wavered; he used his Star articles to rally homefront sentiments against peace until the enemy could be decisively defeated: “let…every one of us, as Canadians, recapture the heroic mood in which we entered the war.”

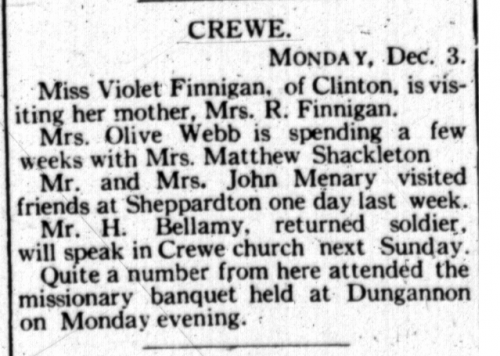

The Signal, 1917-12-06, pg 6

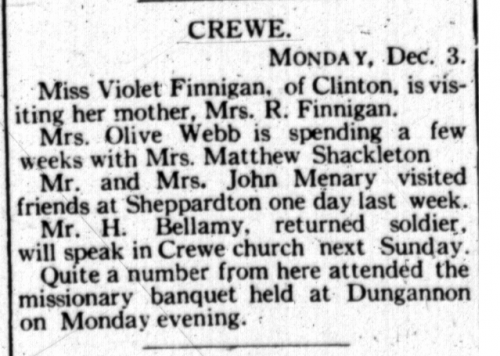

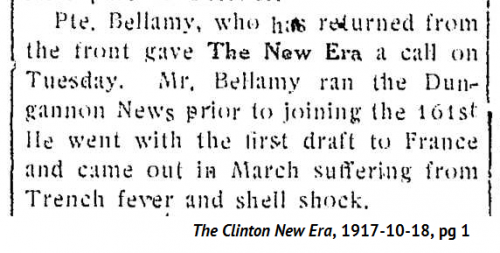

Unable to resume his duties as a soldier, Pte. Bellamy returned to Canada, where in addition to his persistent trench fever, he received a diagnosis of neurasthenia–a contemporary term broadly used for nervous disorders. After his homecoming, he reappeared frequently in the local news columns, usually receiving mention for promoting the war effort at local patriotic events or canvassing for Victory Loans.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

In April 1918, a medical board at Guelph honourably discharged Harry as medically unfit due to illness contracted on active service. His records list a ‘nervous debility,’ as well as trench fever as the causes for his dismissal, and note that “this man would not be able to do more than one quarter of a days [sic] work.” The listed symptoms in his medical records include dizzy spells, light headedness, restlessness, hand tremors, headaches, and an irregular heartbeat. The Board determined that the probable duration of his debility was “impossible to state.”

The Wingham Advance, 1918-06-13, pg 5

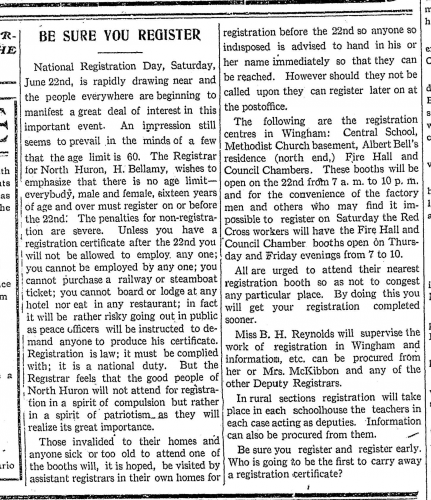

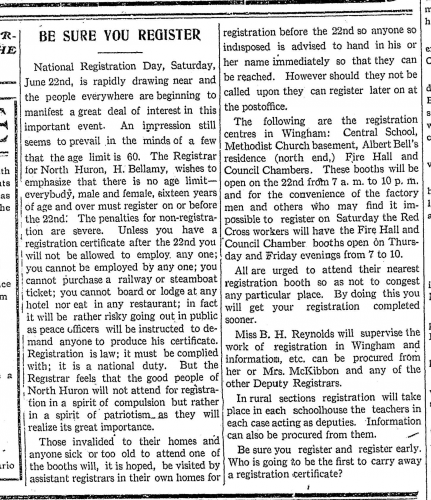

Despite experts’ doubts about his ability to cope with a full-time job, Harry received a temporary government position as North Huron’s Registrar for 1918’s National Registration Day effort. The federal government intended this wartime “man and woman power census” to identify available labour forces for the homefront and overseas by requiring all Canadians over sixteen to register.

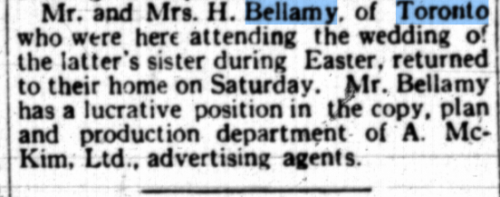

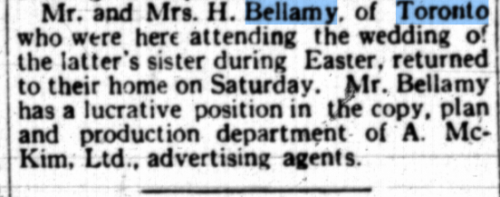

Nothing in the newspapers suggests that Harry Bellamy returned to printing or publishing on a full-time basis in Dungannon. After the war was over in 1919, Ashfield accepted Harry’s application for the township’s annual printing contract with special consideration to him as a “returned soldier,” but according to an item in The Wingham Advance he later declined the work for the pay offered. There was evidently a vocation that Harry Bellamy now felt more passionately for than journalism, because in May of that year the New Era records that he moved to Toronto to accept a bureaucratic position “in connection with the re-establishment of soldiers.” In 1921, Harry ultimately sold The Dungannon News printing equipment to a buyer from Meaford, and he and wife Annie settled permanently in Toronto.They didn’t entirely disappear from print, however, as local news columns over the next decade continued to note the couple’s visits to friends and family in Huron County.

The Signal, 1921-3-31, pg 4

Following Pte. Bellamy’s story via short items in the county papers certainly does not provide a full picture of his life, nor the toll of his experiences in the trenches of France. The information gleaned, though, does speak to the value of these local weeklies as historical resources, and that comparing them against other records–in this case Pte. Bellamy’s military personnel files– can help us to read between the lines. It’s also a pertinent reminder that both historical and news sources are better understood if we know a little about the context and perspective of the people creating them. What emerged in this case was the story of a man whose politics on the page never changed, whose service to the Canadian government continued beyond the battlefield and loyalty to the British empire never faltered, but who nevertheless could not quite pack the personal consequences of war away in an “old kit bag and smile, smile, smile.”

Hot off the Press: Seen in the County Papers opens Nov. 21st at the Huron County Museum! Visit the exhibit to learn more about the stories behind Huron’s historic headlines. You can browse the newspaper collection from the comfort of home at dev.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers. Information for this blog post came from Huron County’s digitized newspapers and Library and Archives Canada’s digitized service records.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.