by Sinead Cox | Aug 25, 2020 | Archives, Blog, Exhibits, Image highlights, Investigating Huron County History

In anticipation of the Huron County Museum’s in-development exhibit Forgotten: People & Portraits of the County, volunteer Kevin den Dunnen takes an in-depth look at one of the many studio photographers to work in Huron County, and traces the professional and personal journey of Irene Burgess.

Summer of 1923 “old home week” in Mitchell, Ontario. Irene is the farthest left of the four. Image courtesy of the Stratford-Perth Archives.

Hiding within the Huron County Museum’s online and free-to-use newspaper archives are an unlimited number of stories like the one of Miss Irene Burgess. Irene Burgess was a woman that defied societal norms. In a time where women were rarely given the freedom to pursue a chosen career, Irene managed her own photography studio. While many women were expected to marry and have families, Irene stayed single. She was also faced with many tragedies in her life. Neither of her two siblings lived past 32. Her mother passed away at 51. Her niece nearly died at the age of 6. She lost the photography studio after an explosion. Through all of this, the communities of Perth and Huron Counties rose to support her.

Personal Life

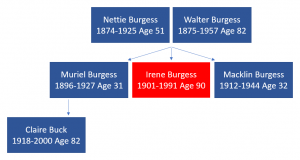

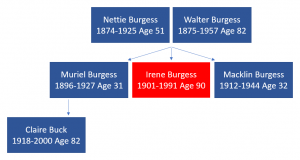

Nettie Irene Burgess was born September 20, 1901, in Mitchell, Ontario. Her parents were Nettie and Walter Burgess. She had two siblings – an older sister named Muriel, born in 1896, and a younger brother named Macklin, born in 1912. Her father, Walter, was a long-time photographer in Mitchell and owner of W.W. Burgess Studio. Growing up around photography gave Irene plenty of exposure to the business. This experience would prove to be important in her adult life.

A brief family tree of the Burgess family. Of note, it only contains the names of family members included in this article.

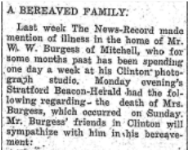

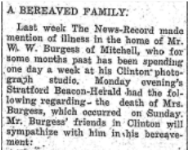

Excerpt from the November 26, 1925, edition of The Clinton News-Record detailing the passing of Irene’s mother Mrs. Nettie Burgess.

Irene experienced several tragedies throughout her life. By her 43rd birthday, only she and her father survived from their family of five. The first to pass was Irene’s mother, Nettie Helena Burgess, on November 22, 1925, at the age of 51. Irene’s sister, Mrs. D.F. Buck ( née Muriel Burgess) and her 6-year-old daughter Claire had been staying with her parents Walter and Nettie Burgess; Mrs. Buck had been ill for some time. During their stay, Claire became ill with pleuro-pneumonia. On the brink of death for several days, she began to recover with the help of her grandmother, Nettie. While caring for Claire, Nettie contracted pneumonia. Less than six days later, Nettie passed away in the presence of her family and nurse. 6-year-old Claire would live for another 75 years thanks to the care of her grandmother.

The next member of Irene’s family to pass would be her sister Muriel. Muriel was married to D.F. Buck, a photographer from Seaforth. They had three children, a daughter named Claire, and two sons named Craig and Keith. On March 24, 1926, an update in the Mitchell Advocate indicated that Irene would be visiting her sister, Mrs. D.F. Buck, at the Byron Sanitorium. According to the update, Mrs. Buck was “progressing favourably” but had been in poor health for some time. Almost fourteen months later on May 12, 1927, The Seaforth News wrote about the death of Mrs. D. F. Buck occurring the past Friday. While not mentioning the cause, the obituary described her as being “in poor health for a considerable period.”

On July 18, 1944, the Clinton News Record posted an obituary for Irene’s brother Macklin Burgess who passed away from a long-time illness at the age of 32. Macklin was in the photography and radio business. He left behind his wife, Elizabeth May, and three children, David, Nancy, and Dixie.

The next of Irene’s family to pass would be her father, Walter Burgess, in 1957 at the age of 82.

An interesting note in the life of Miss Irene Burgess is that she never married. In the Dominion Franchise Act List of Electors, 1935, Irene (age 34) is listed as a spinster (meaning a woman that is unmarried past the age considered typical for marriage). Whenever Irene is referenced in a newspaper, her title is Miss Irene Burgess. Irene would live until 1991.

The Clinton Studio

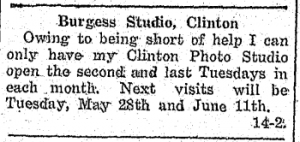

A notice posted by Walter Burgess in the May 23, 1929, edition of The Clinton News-Record

Walter Burgess operated a Clinton studio throughout the 1920s. The November 26th, 1925 edition of The Clinton News-Record mentions that Walter had only been spending one day a week at his Clinton Studio being “short of help.” A notice posted in The Clinton News-Record on May 23 1929 by Walter Burgess stated that his Clinton studio would only be open “the second and last Tuesdays in each month.” On October 1 of 1931, Walter announced that his newly-renovated Clinton studio would be open every weekday. His daughter, Miss Irene Burgess, would now be in charge of the location. Walter proclaimed Irene as “well experienced in Photography” and having “long experience with her father.” Not long after Irene became manager, Clinton residents would see the name Burgess Studios much more often in their newspapers.

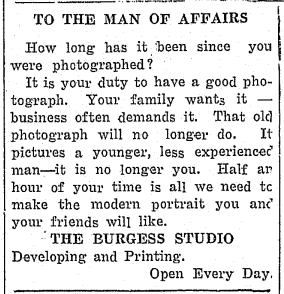

When Irene began managing the Clinton Studio in 1931, advertisements for the business began increasing. The slogan “Photographs of Distinction” appeared in advertisements from 1937 until the week of the fire. These ads were brief, only including the business name, slogan, Irene’s name, and the services provided. Earlier advertisements include one from 1933: “It is your duty to have a good photograph. Your family wants it – business often demands it.” Another example from 1932 reads, “You have plenty of leisure time to get that portrait of [the] family group taken.” The Clinton studio began under the leadership of Walter W. Burgess, but Irene would soon grow the business larger than her father had the time for– that is, until the explosion.

Advertisement posted in the January 26, 1933, edition of The Clinton News-Record.

The Explosion

On the afternoon of Monday, November 24, 1941, an explosion set fire to the second story of the J. E. Hovey Drug Store sweeping the entire business block. This was the place of business for Burgess Studio, Clinton. The fire swept through the building and damaged several businesses including R. H. Johnson Jewelry Store, Charles Lockwood Barber Shop, and Mrs. A MacDonald’s Millinery and Ladies Wear Shop. Irene was not in the studio when the fire started and did not call the authorities. Instead, the fire was discovered by Police Constable Elliot who identified smoke around the second-story window of the J. E. Hovey Drug Store Building. The fire was well covered in local newspapers. Featured on the second page of the Seaforth News more than a week after the incident, it was reported that the fire almost reached the “main business section of the town.” On its front page the week of the accident, The Clinton News-Record described the fire as “one of the most dangerous Clinton firemen have fought for years.” Unfortunately, Irene did not have insurance and was forced to close her business in Clinton. An update written on November 27, 1941 in The Clinton News-Record mentioned Irene’s departure for Mitchell to stay with her father for an “indefinite time.” A week later, on December 4, 1941, Irene posted a notice in the News-Record reading that, “owing to the recent fire damaging my equipment and Studio, I will be unable to continue operation.” She suggested that customers could mail their orders to the new studio. Additionally, customers could drive to her father’s studio in Mitchell and have their travel expenses paid. While this time must have been devastating for Irene, the community came together to show their support for her.

Community Support

Excerpt from the December 12, 1941, edition of the Huron Expositor describing an even held in Irene Burgess’ honour.

Two weeks after the explosion, the Mitchell Advocate reported about an event held at the I.O.O.F. Hall where Irene was the “honoured guest.” The event was planned by Irene’s friends Mrs. Dalton Davidson, Mrs. Earl Brown, Mrs. Harold Stoneman, and Miss Florence Paulen. Entertainment included skits, piano music by Mrs. A. Whitney, cards, and a “bountiful lunch.” Irene received a “purse of money” and personal gifts from her friends along with their condolences. The rallying support for Irene shows the positive impact she had in the communities of Clinton, Seaforth, and Mitchell. An uplifting end to an otherwise sad story.

Conclusion

Aside from her brother’s passing in 1944, Miss Irene Burgess was seemingly never mentioned again in the Huron County Newspapers accessible through the digital newspaper portal. She would live until 1991 in St. Marys, Ontario.

Huron County’s digitized newspaper collection is a vast historical database where you can find historical stories from our own county. While performing research for the upcoming exhibit “Forgotten: People & Portraits of the County,” I came across this story which piqued my interest. Without access to the digitized newspaper collection, the story of Irene’s remarkable journey would never have been found. This post was compiled using newspaper articles between the years of 1925 and 1944. Birth and death dates were found within newspapers and using external resources.

If you have a photograph by a Huron County photographer you would like to donate or share, please contact the Museum’s archivist by calling 519-524-2686, ext. 2201 or email mmolnar@huroncounty.ca. To learn more about the Huron County Archives & Reading Room, visit: https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/huron-county-archives/

A950.1857.001 A photograph taken by Burgess Studio Mitchell in 1914. If you have a photograph from Burgess’ Studio, Clinton you would like to donate, please consider contacting the Huron County Museum.

by Sinead Cox | Jun 4, 2020 | Investigating Huron County History

Curator of Engagement and Dialogue Sinead Cox shares the story of a historical quarantine in the summer of 1916.

Although you may have heard (to the point of cliché) that we are living in ‘unprecedented times’ during today’s COVID-19 pandemic, communities across Huron County have seen quarantines and the temporary closure of schools and businesses before. Although usually on a much smaller and localized scale, these actions in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were in response to contagious illnesses that included influenza, measles, diphtheria, scarlet fever, smallpox, whooping cough and typhoid among others.

From The Brussels Post, July 27th, 1916.

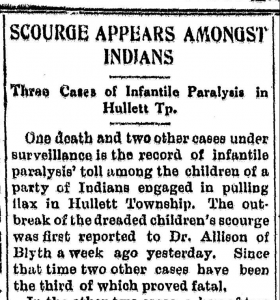

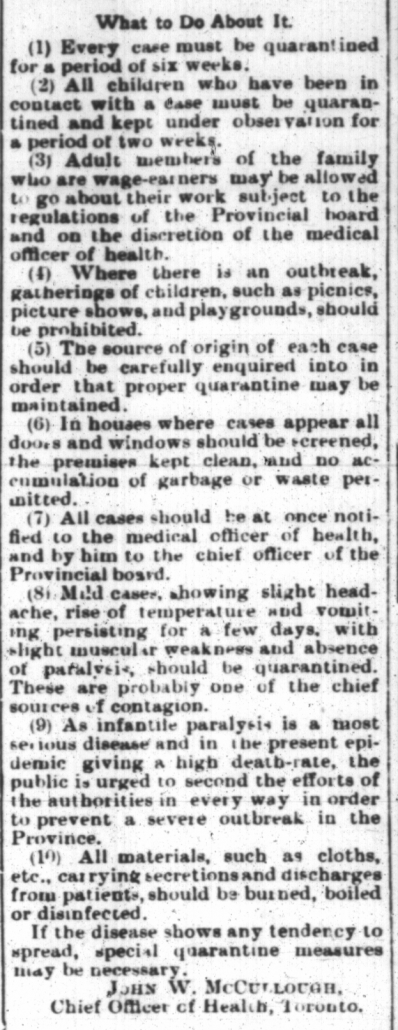

In 1916 an outbreak of infantile paralysis (polio or poliomyelitis) hit North America. The poliovirus is most dangerous to children under five years of age and in serious cases can cause permanent and debilitating nerve and muscle damage to survivors if non-fatal. The 1916 epidemic was particularly devastating in New York and then appeared in Canadian cities like Montreal before eventually arriving in southern Ontario. In Ontario, the provincial Medical Board of Health enacted quarantine regulations and required doctors to report all cases or face prosecution.

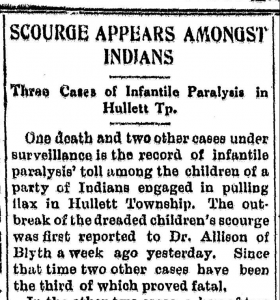

The outbreak had reached Huron County by July, when a fourteen-month-old girl in Varna died: only the second fatal case confirmed in Ontario up to that point. Panic hit the next month when three young children in Hullett Township contracted the much-feared disease. The children had come to live temporarily in Hullett (now part of the Municipality of Central Huron) with their parents during the flax harvest, but their permanent home was reported as ‘Muncey Reserve.’ Indigenous families from Southwestern Ontario reserve communities, including those on the shore of the Thames River south of London and also Saugeen First Nation to the north, were a crucial labour force for annual flax harvests in the early twentieth century. Entire families moved seasonally to pull flax for Huron growers; they worked and lived in close contact with each other, camping alongside their worksites.

The sick children belonged to a group of about 15 families living in tents roughly six miles from Clinton when the infantile paralysis struck-eventually infecting two five-year-olds and a two-year-old. A local Blyth doctor treated the first cases and told the area newspapers that the farm workers’ living situation presented a challenge for protecting the lives of the other 23 children in the camp: “Isolation and quarantine, so necessary for the treatment of infantile paralysis, are something hard to enforce in any Indian reservation or encampment…We are doing what we can to prevent any spread of the disease, and watching for further symptoms, but it is next to impossible to enforce the requisite isolation.” The vast majority of poliovirus cases are completely asymptomatic. The disease can spread through direct contact or via contamination by human waste.

From the Wingham Advance, August 31st, 1916.

For one of the five-year-olds, the virus was tragically fatal on August 25th, but the other two children soon appeared to be recovering. Local newspapers did not identify any of the camp members by name, but a death registration reveals that the little girl who lost her life was Annie Corneolus, the five-year-old daughter of Abram and Elizabeth. She was ill only one day, but the polio had caused lethal ‘paralysis of respiration.’ Her birthplace is recorded as Oneida Reserve (Oneida Nation of the Thames). Annie’s burial took place at Burns Cemetery, Hullett. Local health officials separated the families with sick children from the rest of their neighbours and they proceeded to quarantine at a farmer’s house on the 11th Concession. School Section # 11 at Londesborough cancelled classes for all students as a precaution.

Fortunately, their quarantine appeared successful and there were no further cases reported. The Clinton New Era announced that “the infantile paralysis scare in Hullett Township has pretty well blown over.” When health authorities lifted quarantine the families impacted returned to their reserve community, and the rest of the camp moved on to Blyth to continue their flax-pulling work. The Huron newspapers make no mention of whether or not the surviving children suffered any long-term health effects. Later reports listed the total number of province-wide infantile paralysis cases at 64 for July and August of 1916, with 8 resulting deaths–meaning that 25% of those total polio deaths occurred in Huron County.

From the Signal (Goderich), July 20th, 1916.

There is no cure for polio, but the Salk vaccine of 1955 would eventually be effective and widely used to prevent the disease; after continuous deadly outbreaks throughout the first half of the twentieth century, childhood vaccinations have eradicated polio in Canada.

The living and working conditions of temporary farm workers in 1916 would have made following advice about precautionary hygiene and social distancing almost impossible to follow-and many people in Canada are facing those same challenges today, without equal housing or opportunities to practice self-isolation under novel coronavirus. Although the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic is not the same as polio, the reality that Indigenous communities continue to be disproportionately impacted by pandemics, and that temporary and migrant workers are at a higher risk because of a lack of resources and opportunities to safely distance is absolutely precedented.

More Info about the history of polio in Canada: https://www.cpha.ca/story-polio

*Note: I wrote this blog post using contemporary newspaper accounts including the Wingham Times, The Wingham Advance, The Lucknow Sentinel, The Clinton New Era, The Clinton News-Record, the Signal (Goderich) and others, all accessed from Huron’s free historical newspaper database: https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers/ Annie’s death documentation was accessed via Ancestry.ca (Archives of Ontario; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Collection: MS935; Reel: 220). All of these accounts were written from a settler point of view (as is my own), and the newspapers did not include the voices or even the names of the community members impacted. If you have any further information you’d like to share about this outbreak or similar outbreaks in the past contact museum@huroncounty.ca.

by Sinead Cox | Aug 8, 2017 | Artefacts, Investigating Huron County History

This is the second instalment of a four-part series, Unsafe in any County, by Special Project Coordinator Jeremy Dechert. The series focuses on the dangers posed by historic automobiles or automobile components and is inspired by the Museum’s growing database of digitized historical newspapers from across Huron County. These newspapers can be accessed by visiting our website. In our first instalment, we focused on the dangers of the 1953 Buick Roadmaster’s braking system.

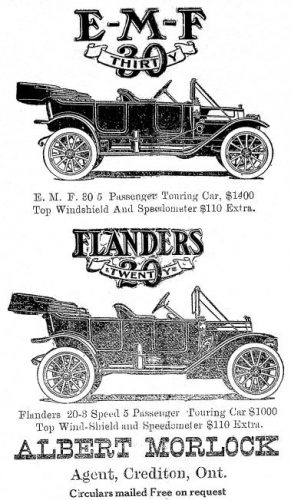

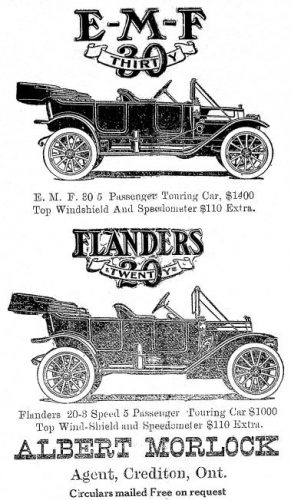

This week, we will be focusing on the dangers and innovations of early automobile windshields. Windshields were first introduced as optional vehicle components in 1904. Automobile manufacturers such as Ford and Cadillac offered windshields as standard equipment as early as 1911 while other manufacturers such as Studebaker, EMF, and Flanders offered windshields as optional equipment available at an extra cost. Windshields were not standard features on most vehicles until 1915.

The Herald. May 24, 1912 p.5

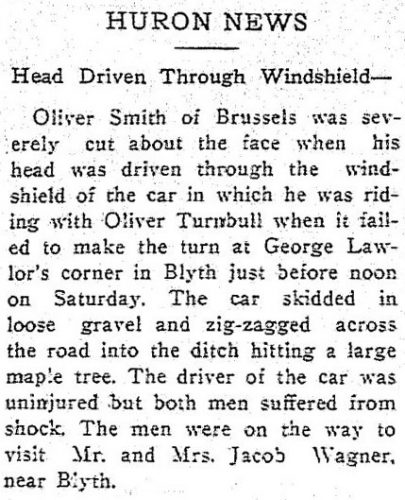

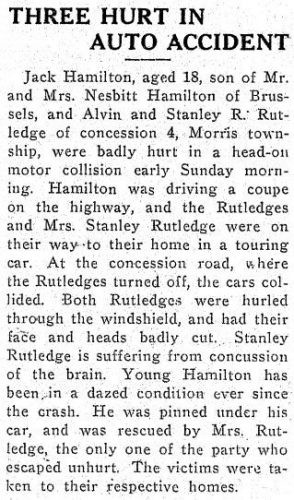

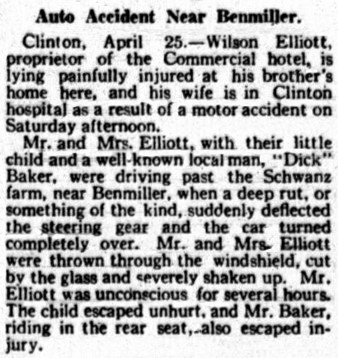

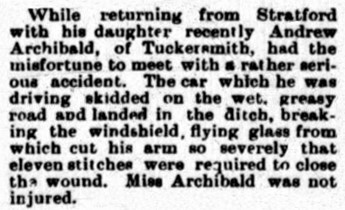

Originally, windshields were made with single sheet plate glass. The 1925/1926 Essex Super Six, originally owned by the Museum’s founder Mr. Neil, and on display here at the Huron County Museum, has a windshield made of plate glass. This glass was effective for keeping bugs, debris, water and snow out of a vehicle. However, should an accident occur, it was less successful at keeping the driver or passenger(s) in. They could easily be ejected through the window or the glass could break into large, sharp pieces which were liable to cause injuries. There are numerous accounts of such injuries occurring in Huron County as seen in local newspaper articles.

The Seaforth News. September 15, 1938 p.2

The Wingham Advance. May 15, 1930 p.1

The Signal. April 29, 1920 p.8

The Signal. June 21, 1917 p.7

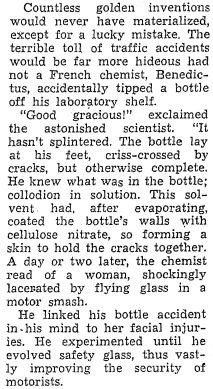

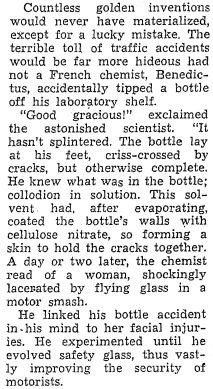

In 1909, there was a major development in glass technology: safety glass. Safety glass does not break as easily as plate glass. It is intended to crack and splinter rather than shatter when impacted. This type of glass helps to prevent occupants from being ejected from the vehicle in the case of a crash, provides more rigidity to the car frame in the case of a rollover, and makes it more difficult for thieves to break into a vehicle. The August 2, 1956 edition of the Zurich Herald included a concise explanation of how safety glass was invented by French Chemist Edouard Benedict…by accident.

Zurich Herald. August 2, 1956 p.6

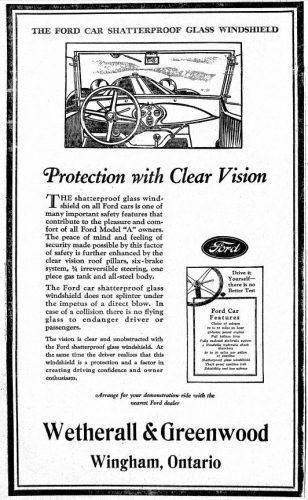

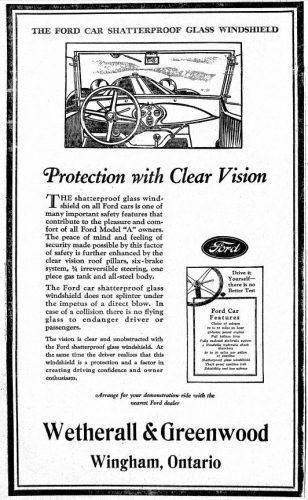

Wingham Advance-Times. July 18, 1929 p.2

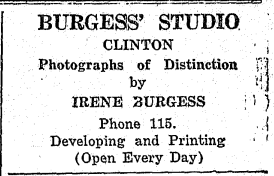

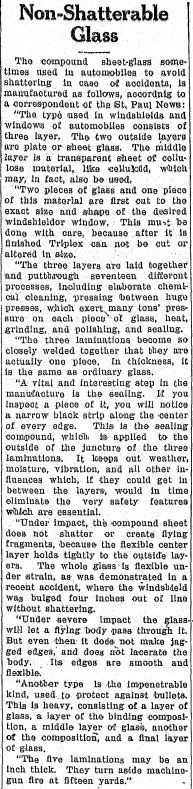

Two decades after its invention, Ford was the first vehicle manufacturer to include safety glass as a standard feature on a vehicle under $1500. Meaning, Ford was the first company to put this new windshield in front of the average consumer. Beginning in 1929, triplex safety glass windshields were a standard feature on all Ford models. This triplex glass consisted of three layers. The outer two layers were made of regular sheet glass and the inner layer was made of cellulose, giving the windshield rigidity and form. In 1928, The Seaforth News ran an article describing the manufacturing process for “Non-Shatterable Glass.”

Seaforth News. July 12, 1928 p.7

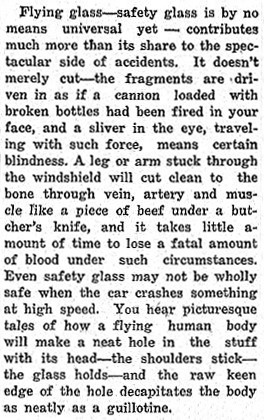

Although the invention of safety glass undoubtedly saved many drivers and passengers from injury and death, it did not avoid criticism. In 1937, The Department of Highways (US) outlined the shortcomings of safety glass in an article titled Automobiles – and Sudden Death. Though sensationalist in tone, the article notes the danger of partial occupant ejection during automobile accidents. According to the article, the safety glass could “guillotine.” Ralph Nader echoed this concern in 1965. He specifically criticized the quality of safety glass. He named safety glass windshields as the third greatest culprit in causing injury during automobile accidents. He argued that while safety glass windshields often prevented an occupant from fully leaving the vehicle, they did not protect occupants who were only partially ejected. The glass would act as a jaw when the occupant’s momentum came back towards the vehicle following the initial impact. Safety glass has progressed immensely since 1965 but this great innovation was not an instant solution to a serious safety issue facing motorists. For more automobile history, visit our website and search our growing collection of digitized newspapers from across Huron County.

excerpt: “Automobiles – and Sudden Death,” Clinton News Record September 2, 1937 p.7