by Sinead Cox | Mar 30, 2020 | Artefacts, Collection highlights, Exhibits, For Teachers and Students, Uncategorized

Huron County Museum: Virtual Permanent Galleries

The Huron County Museum’s virtual exhibits grant a close-up glimpse of select artifacts on permanent display in our galleries, as well as information that you can’t guess with just a look. The featured objects represent a small sampling of the thousands of artifacts in the museum’s collection. Updating the online exhibits is an ongoing project; in the future, student employees will be refreshing the images and providing even more information. These exhibits are also available via ipads onsite when the museum is open.

Huron County Main Street

Our Main Street features real storefronts and objects from across the county of Huron.

Click the storefront names to step inside and see artifact highlights!

Military Gallery

Click the titles below to see archival documents and more related to Huron County and the First World War.

Huron County Museum Feature Gallery: Virtual Exhibits

The Huron County Museum rotates exhibits of special interest through the year in our Feature Galleries. Click to explore past temporary exhibits that you may have missed or want to rediscover.

by Sinead Cox | Mar 18, 2020 | Blog, Investigating Huron County History

Beth Knazook, Special Project Coordinator for Huron’s digitized newspaper project reviews the bitter rivalry between Huron’s first newspaper editors. You can search the newspapers yourself for free at https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers/

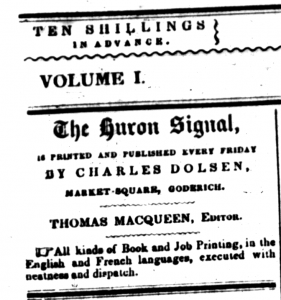

The Signal was the first newspaper printed in Huron County, beginning on February 4, 1848. Published in Goderich by Charles Dolsen, and edited by Thomas Macqueen (or “McQueen”), it promised to deliver “as many Essays and as much knowledge on all subjects of practical importance, as our space and time will reasonably allow,” Huron Signal (February 4, 1848), 2.

The Signal was the first newspaper printed in Huron County, beginning on February 4, 1848. Published in Goderich by Charles Dolsen, and edited by Thomas Macqueen (or “McQueen”), it promised to deliver “as many Essays and as much knowledge on all subjects of practical importance, as our space and time will reasonably allow,” Huron Signal (February 4, 1848), 2.

Macqueen was born in Ayrshire, Scotland, where he gained some fame as a poet and an accomplished lecturer. He immigrated to Canada and lived with his sister in Renfrew, Ontario, where he worked briefly as editor of The Bathurst Courier (Perth) before moving to Goderich to take up the position of editor for the Huron Signal. Instead of focusing only on local news, Macqueen brought literature, political, and cultural news from afar to the Western frontier of Canada. In its first issue, he ran articles detailing the history of Cortez’s conquest of Mexico, a travel account of Smyrna, and tales of “The Bushman” living in the Australian outback. He covered scientific news as well, re-printing snippets from other papers containing new information about exciting discoveries like electricity. He also included his own poetry, and encouraged others to contribute poems and songs.

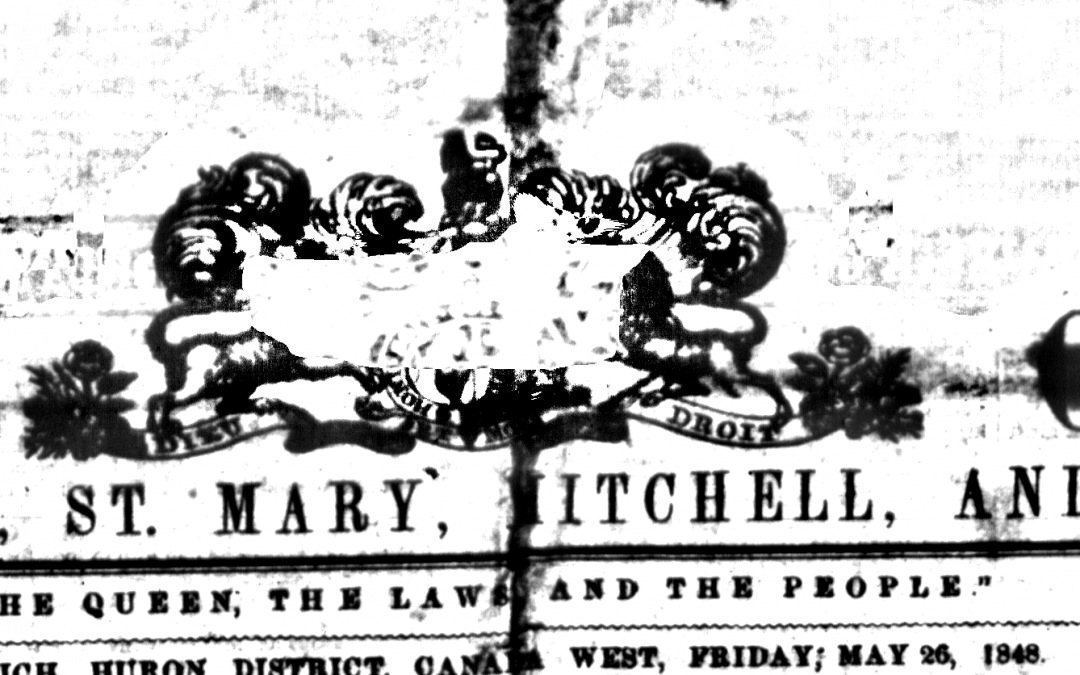

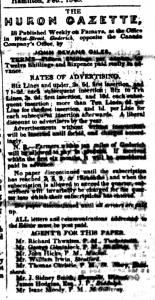

The Huron Gazette began publishing a few weeks later, on February 25, 1848, offering a conservative counterpoint to the Huron Signal’s liberal voice. There are fewer surviving copies of the Gazette from which to piece together the history and contents of the paper, but it seems to have been more practical in its aims. Local advertisements appeared alongside snippets of home and foreign news, dispatches from British Parliament, and editorials – with some entertaining fictional stories thrown in the mix. By late May, the paper had become so popular that editor John Beverley Giles considered either using larger paper sheets or going to a semi-weekly delivery to fit in more content. “We thank our kind supports for the patronage that has demanded from us this alteration, and we think it will evidence to the Province in general the enterprise and intelligence of the Huron Tract,” Huron Gazette (May 26, 1848), 2.

The Huron Gazette began publishing a few weeks later, on February 25, 1848, offering a conservative counterpoint to the Huron Signal’s liberal voice. There are fewer surviving copies of the Gazette from which to piece together the history and contents of the paper, but it seems to have been more practical in its aims. Local advertisements appeared alongside snippets of home and foreign news, dispatches from British Parliament, and editorials – with some entertaining fictional stories thrown in the mix. By late May, the paper had become so popular that editor John Beverley Giles considered either using larger paper sheets or going to a semi-weekly delivery to fit in more content. “We thank our kind supports for the patronage that has demanded from us this alteration, and we think it will evidence to the Province in general the enterprise and intelligence of the Huron Tract,” Huron Gazette (May 26, 1848), 2.

Perhaps a rivalry between the editors of these two papers was inevitable given their political leanings, but Mr. Giles appears to have had a particular talent for provoking the Signal’s Thomas Macqueen. His commentary in the Gazette frequently took the form of very personal attacks, which in turn provoked exasperated and increasingly angry responses in the Signal. Accusations made about the conduct of Mr. Macqueen on the occasion of the annual Agricultural Society’s Show in 1848 prompted several surprised and supportive letters to the editor condemning the malicious gossip in the Gazette.

Thomas Macqueen’s frustration with the Gazette seems to have reached its limit when he declared “We think Mr. Giles is unfortunate in every thing he takes in hand, and still more unfortunate when he tries the pen. His paper will soon be unable to contain his answers to the remonstrances of those he has offended by his impudence. We think he should give it up, —or if not, he should cease to be guided or counselled by those reckless inexperienced characters who are driving him to misery and disgrace for their own vain and selfish purposes, and who lately forced him to insult the respectable community of Goderich under the designation of ‘bare-footed boys and slip-shod girls,’” Huron Signal (May 12, 1849), 2.

Not many issues of the Huron Gazette have survived to explain Mr. Giles’ side of the story, but we do know that in June of 1849, Mr. Macqueen’s predictions about the Gazette’s impending doom were proven right. Mr. Giles abandoned the editorship of the Gazette, although the paper survived a little while longer under editor(s) who seem to have wanted to keep their names hidden. The Huron Signal reported at one point that “nobody is the Editor of it, and nobody will take the responsibility of it. It is not read by 50 men in the District of Huron, and of that fifty, there are not five who attach the slightest credit to any of its statements,” Huron Signal (June 22, 1849), 2. When the Gazette ceased publication in 1849, Mr. Giles left town – but not the newspaper business. He would take up the editorship of the St. Catharines Constitutional, hopefully with better results.

Inkwell used by Thomas McQueen. 1978.10.1. Collection of the Huron County Museum.

Macqueen edited the Signal until his death in 1861 at the age of 57, at which point J.W. Miller took over as editor while the publishing side was managed by Macqueen’s son-in-law, T. J. Moorhouse. The paper was then sold to William T. Cox, who ran it until 1870, and from there it changed hands many more times over the years. The Huron Signal survives today in the form of the Goderich Signal Star. Over the course of the paper’s long history, there has been a lot more (friendly) competition in the Huron County weekly news business.

by Sinead Cox | Nov 6, 2017 | For Teachers and Students, Investigating Huron County History

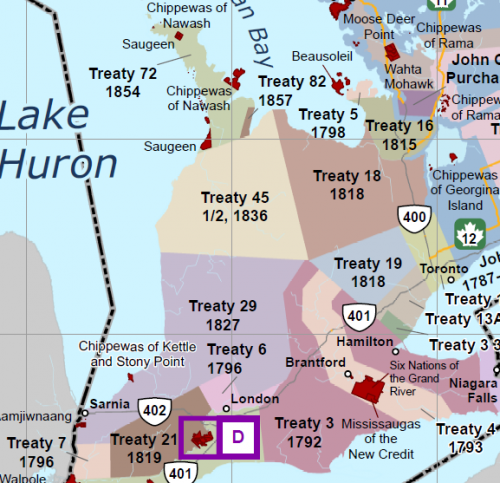

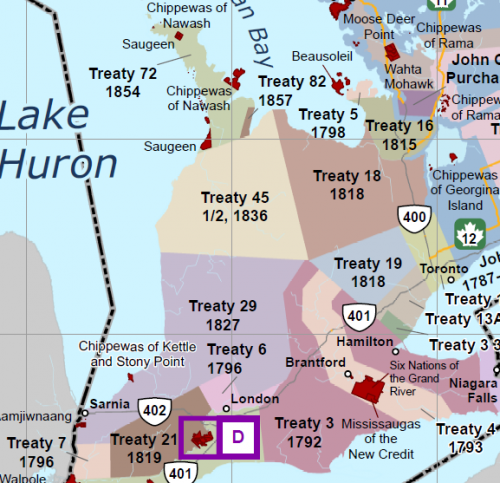

What is now Huron County includes parts of the traditional territories of multiple Anishinaabe communities. Liz Duern is a current University Student, and worked as a Museum Assistant at the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol during the summer of 2017. In this guest blog post for Treaties Recognition Week, Liz shares what she learned during her initial research into the treaty history of this area.

What is a Treaty? How were they created? Treaties are agreements between First Nations and the British Crown. While the Crown used treaties to gain access to land for settlement and mining, First Nations understood treaties as building nation-to-nation relationships and protecting their continued stewardship of the land. The Crown often promised to protect First Nations’ rights and to set aside tracts of land for the exclusive use of the First Nations and their members. Today, the elders of many indigenous communities hold a great amount of knowledge regarding the intent of the treaties passed down through oral history.

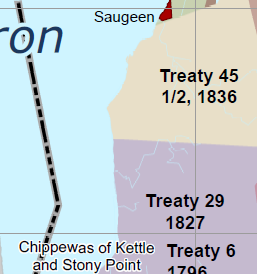

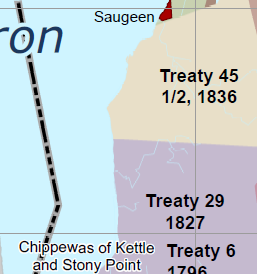

Detail from https://files.ontario.ca/firstnationsandtreaties.pdf

Treaty 29: Following earlier provisional agreements, the Huron Tract (1827) The Huron Tract Treaty was signed by eighteen Anishinaabek chiefs in 1827 in Amherstburg; in addition to what is now Lambton County and part of Wellington under settler municipal boundaries, the Huron Tract included most of what would become the Huron District-most of Huron County and parts of Perth & Middlesex. This treaty ceded 99% of the communities’ remaining lands to the British Crown, and designated four reserves: one along the south of St. Clair Township, one at Sarnia, and two on Lake Huron (Kettle and Stony Point).

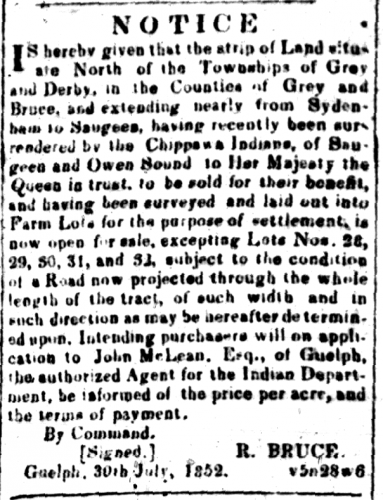

Treaty 45 ½: The Saugeen Treaty (1836) Treaty 45 ½, signed on August 9, 1836, dealt with part of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation’s traditional territory. The British promised the Saugeen Ojibway Nation that they would protect the Indigenous peoples who resided on the Saugeen Peninsula and that the Saugeen Peninsula would be protected for their use. Not long after this, the British claimed that the Saugeen Peninsula could not be protected against settlers unless another treaty was negotiated. This treaty was Treaty 72, which ceded about 500,000 acres of the Saugeen Peninsula to the British Crown.

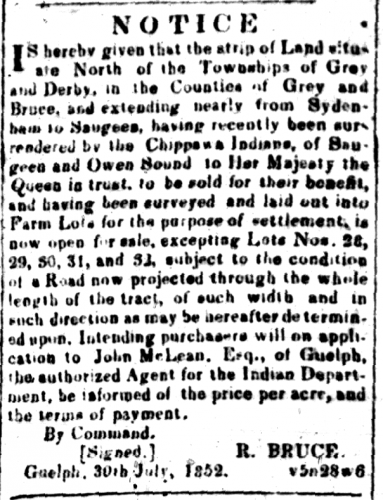

Huron Signal, 1852-09-16, page 4

via https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers/

Treaties are not just historical documents, but outline ongoing rights and responsibilities that are protected by the Constitution Act, 1982. These rights and the spirit of the original agreements have often been violated “by colonial policies designed to exploit, assimilate and eradicate” First Nations communities and their cultures. Access teaching resources to better understand what it means to live on Treaty Land.

by Sinead Cox | Aug 24, 2015 | Huron Historic Gaol, Project progress

The Huron Historic Gaol was an operational jail from 1841 until 1972. Many Huron County residents still remember the building when it housed inmates, as well as the governor or superintendent (jailer) and his family in the adjoining house; museum staff wanted to hear their stories to gather a more complete picture of day-to-day life living or working in jail. This summer, student museum assistant Mackenzie Bonnett met interview-partners with memories of the building prior to its 1972 closure at the gaol; he shares his first experiences with oral history.

Following the recent death of a former notable gaol employee, the Huron Historic Gaol and the archives at the Huron County Museum received a series of inquires into their life and time spent at the Gaol. Through these inquiries staff realised there is relatively little we know about the personal experiences of those that spent time at the Gaol while it was still in operation. We decided that the best way to learn more about these stories would be to get them directly from the source; this started my summer Gaol oral history project.

Following the recent death of a former notable gaol employee, the Huron Historic Gaol and the archives at the Huron County Museum received a series of inquires into their life and time spent at the Gaol. Through these inquiries staff realised there is relatively little we know about the personal experiences of those that spent time at the Gaol while it was still in operation. We decided that the best way to learn more about these stories would be to get them directly from the source; this started my summer Gaol oral history project.

I sought out people with any connection to the Gaol whether they were inmates, guards, maintenance staff, volunteers or family of the governor (jailer). A press release was sent out in early June to various local newspapers asking anyone with these types of connections to contact the gaol. Before starting any interviews I had to prepare myself with questions to organize and keep focus during the interview. I also had to prepare for the logistics of an oral history project which requires consent and release forms which allow people to assign a future date for when the information from their interview can be used.

Over the summer I conducted three interviews that each had their own interesting stories that told a variety of things about the Gaol and its staff and inmates that were not known to our staff today. I heard stories from friends and family of past Gaol Governors that heard firsthand accounts of day to day operations of the Gaol including escape attempts and notable prisoners. I also heard from Gaol volunteers that gave important insight into how the Gaol and its inmates were viewed by the community it served. I hope that the stories I heard and transcribed can be use in the future to aid with research and the creation of further exhibits.