by Sinead Cox | Oct 11, 2021 | Blog, Collection highlights, Exhibits, For Teachers and Students

If you are a teacher or student looking for local stories from Huron County for your Remembrance Day lessons or assignments, you can access the Huron County Museum’s collection from home and your classroom through our virtual offerings! These resources speak both to Huron County’s military history and to the home front during the First and Second World Wars.

Videos

Our War: Home Front

Our War: Nursing Sisters

Young Canuckstorians: The Maud Stirling Story

Jack McLaren: A Soldier of Song features a presentation and performance from author and musician Jason Wilson, based on the original works of the Dumbells, a Canadian concert party that entertained the troops on the front lines in World War I and featured Jack McLaren (later a resident of Benmiller).

The History of Drag Makeup Tutorial with Lita explains how drag performers improvised wigs, makeup and clothing at the front lines.

A reading of a WWII letter from R.C.A.F Pilot Officer Alan H. Durnin to Mrs. C. Blake of RR 1 Dungannon

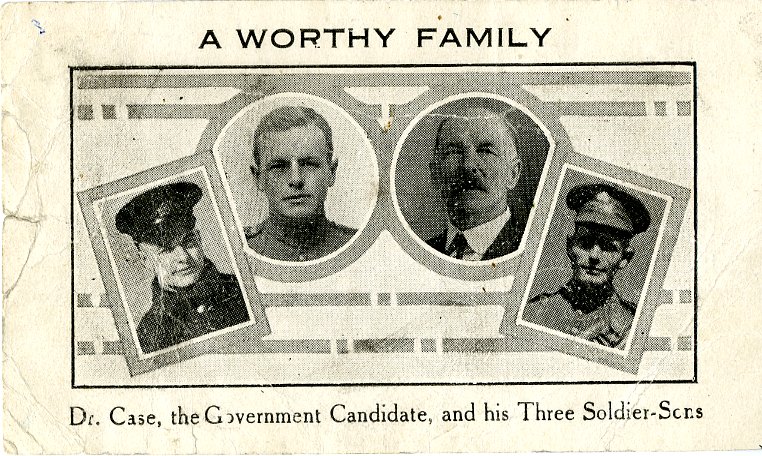

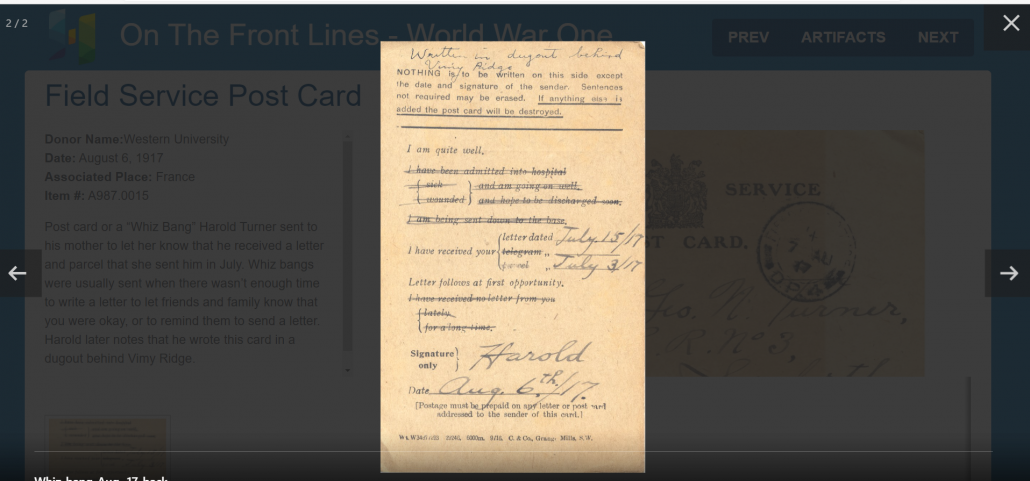

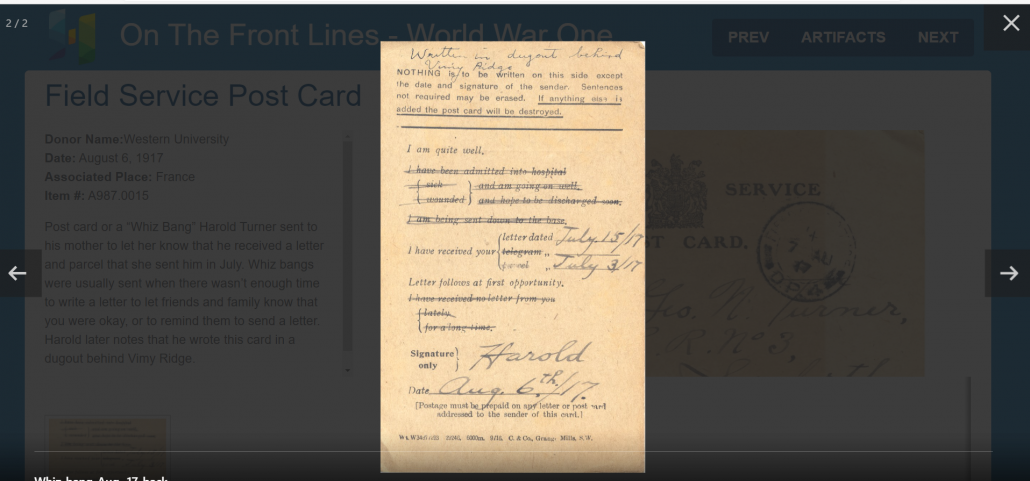

On the Front Lines: Word War One virtual exhibit.

Virtual Exhibits

Part of the museum’s collection of photographs by local photographer J. Gordon Henderson have been digitized. During World War II, he travelled to air training schools in Goderich, Port Albert, and Clinton taking pictures of classes and other base activities. Many airmen came to his studio in Goderich to have their portraits taken to send home to family and friends. The Henderson Collection also includes wedding portraits, candid shots, correspondence and interviews with airmen related to WWII air training in Huron County. Access the virtual Henderson collection by clicking here!

You can also browse more photographs via our Flickr page!

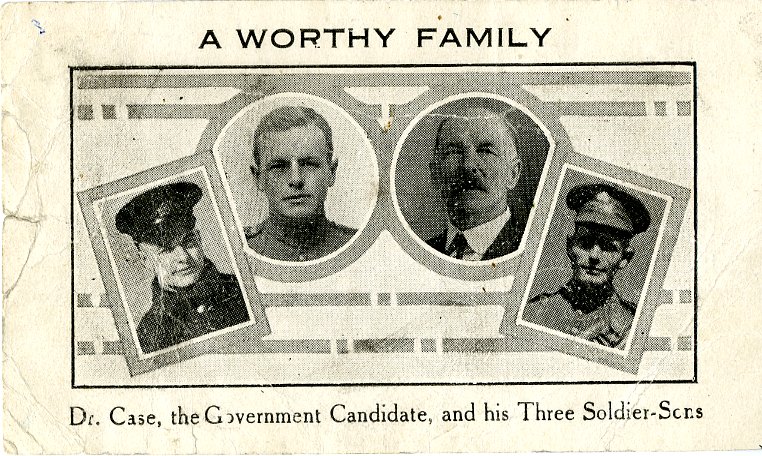

See archival documents from the Huron County Museum’s collection in our Military Gallery virtual exhibits:

On the Front Lines: Word War One

The Home Front: World War One

Prominent artist and Benmiller resident J. W. (Jack) McLaren fought with the Princess Patricia Canadian Light Infantry in WWI, and entertained troops at Ypres Salient, Vimy Ridge and many other locations on the Western Front with the PPCLI Comedy Company and the 3rd Division Dumbells Comedy Troupe. Find out more about Jack and entertaining at the front through the virtual version of our 2020 Reflections exhibit, which was presented in partnership with the Huron Historical Society.

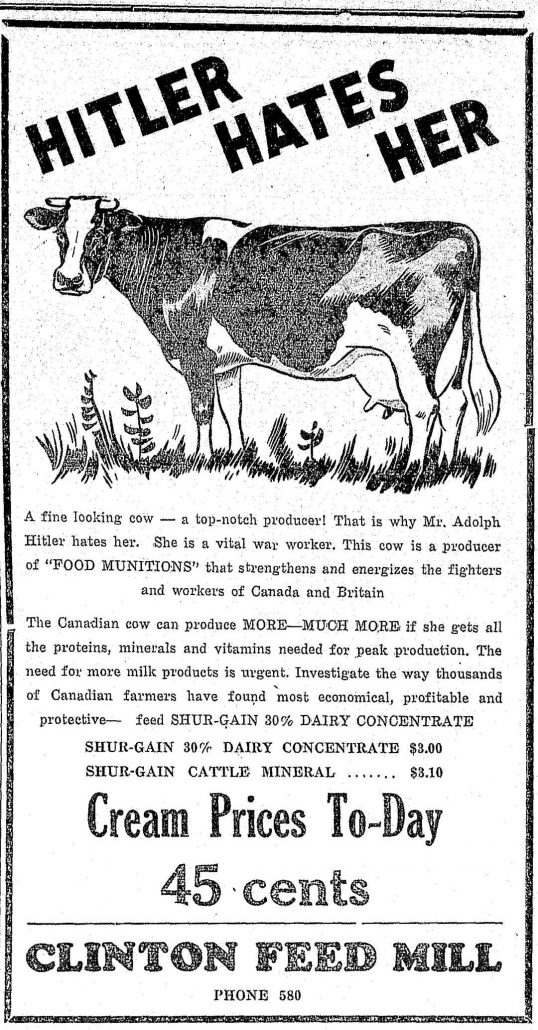

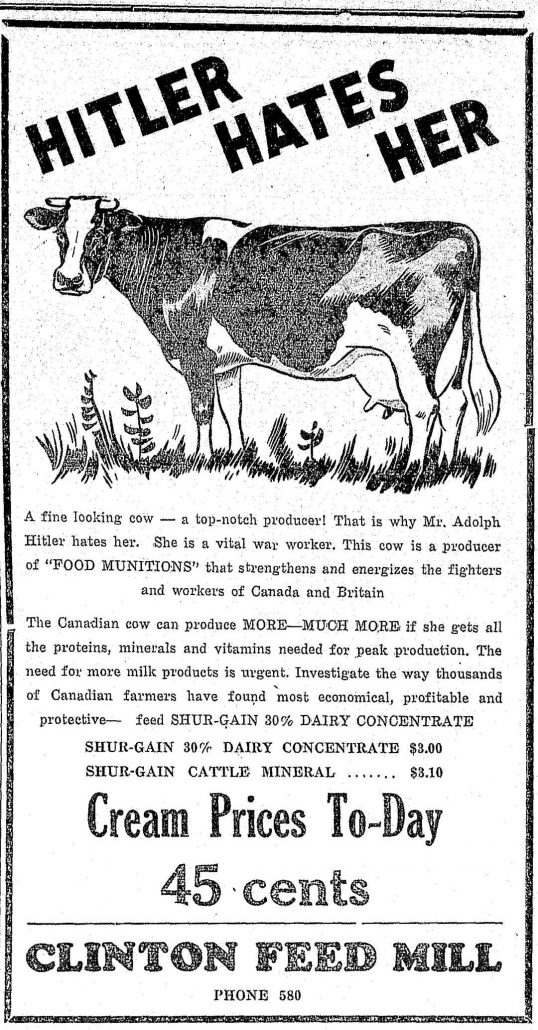

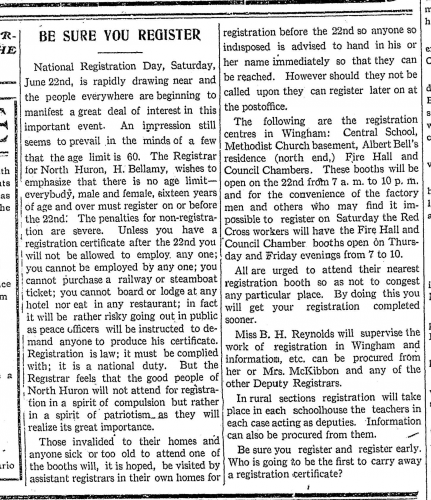

Clipping from Huron County’s digitized newspapers. This ad appeared in the Clinton News-Record in 1942 and 1943.

Articles & Short Posts

A Closer Look: The M4A2E8 Sherman Tank

The Huron Jail & the Second World War Part 2: A STRANGE MUTINY ON THE GREAT LAKES

The Huron Jail & the Second World War Part I: THE ‘DEFENCE OF CANADA’ IN HURON COUNTY

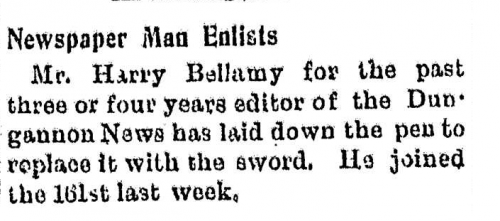

Newspaper Man Enlists: Huron County and the First World War in Black & White

Collection Highlights from Remembrance Day 2014

The Mystery of the 4th Toe on the Left Foot

Local Girl Leaves for the Front

Love is in the Air

Dogs of Air Training (Part 2)

Dogs of Air Training (Part 1)

Education Programs

The Huron County Museum’s ‘Huron County and the World Wars’ program is recommended for grades 5-10, and is offered as both an in-person and virtual field trip. There is also public outreach available by request with our Huron County home front reminiscence kits. Click here to find out more about our Education Programs.

Email museum@huroncounty.ca to inquire about booking an in-person or virtual program.

Research Resources

Click to search more than a century of history via Huron County’s digitized newspapers: free, online and keyword searchable. The newspapers provide a wealth of information on local soldiers and nursing sisters, including casualty reports and letters from the front. You’ll also find detailed information about life and work on the home front, including wartime advertising.

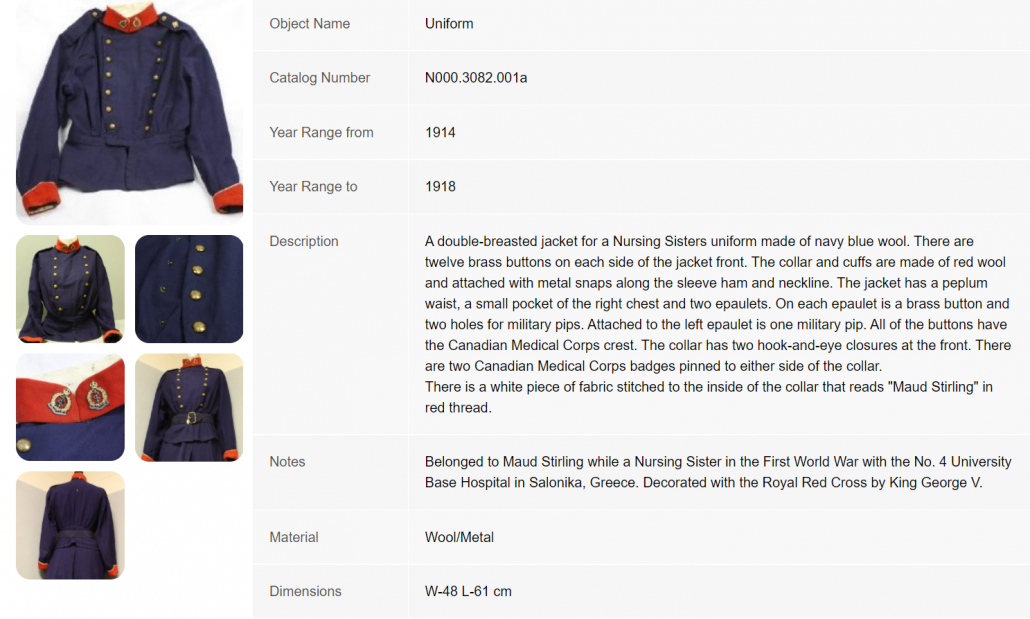

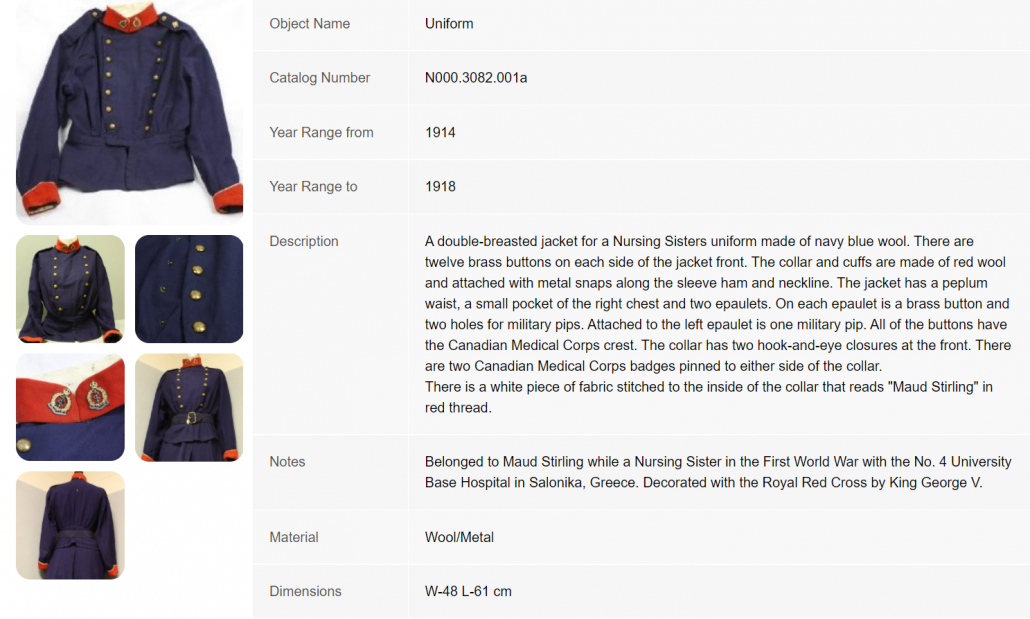

Or Click here to search a selection of the museum’s archives and artifacts via our online collection. Relevant artifacts include uniforms, photographs, medals and memorabilia from British Commonwealth Air Training bases in Huron.

Book List Check out this reading list related to local WW1 and WW2 history, available through the Huron County Library.

Nursing Sister Maud Stirling’s uniform in the Huron County Museum’s searchable online collection.

by Sinead Cox | Jun 4, 2020 | Investigating Huron County History

Curator of Engagement and Dialogue Sinead Cox shares the story of a historical quarantine in the summer of 1916.

Although you may have heard (to the point of cliché) that we are living in ‘unprecedented times’ during today’s COVID-19 pandemic, communities across Huron County have seen quarantines and the temporary closure of schools and businesses before. Although usually on a much smaller and localized scale, these actions in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were in response to contagious illnesses that included influenza, measles, diphtheria, scarlet fever, smallpox, whooping cough and typhoid among others.

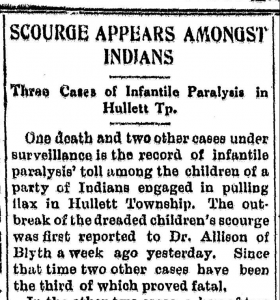

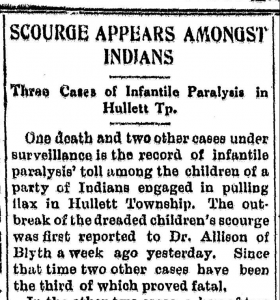

From The Brussels Post, July 27th, 1916.

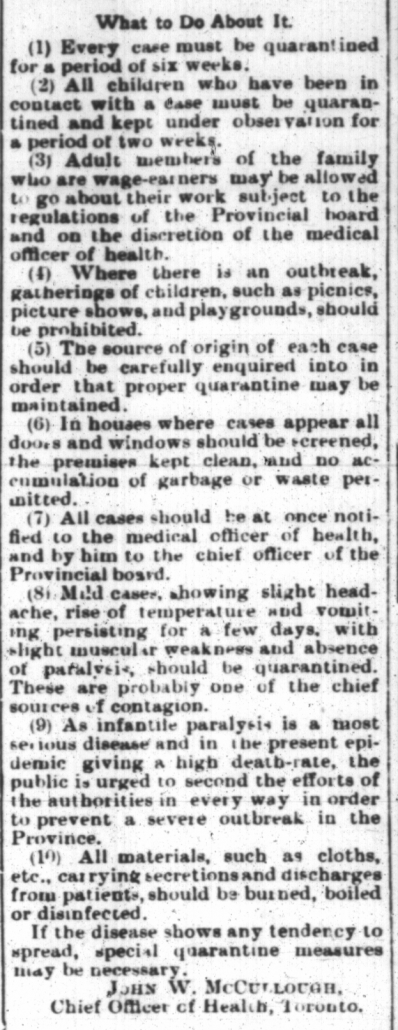

In 1916 an outbreak of infantile paralysis (polio or poliomyelitis) hit North America. The poliovirus is most dangerous to children under five years of age and in serious cases can cause permanent and debilitating nerve and muscle damage to survivors if non-fatal. The 1916 epidemic was particularly devastating in New York and then appeared in Canadian cities like Montreal before eventually arriving in southern Ontario. In Ontario, the provincial Medical Board of Health enacted quarantine regulations and required doctors to report all cases or face prosecution.

The outbreak had reached Huron County by July, when a fourteen-month-old girl in Varna died: only the second fatal case confirmed in Ontario up to that point. Panic hit the next month when three young children in Hullett Township contracted the much-feared disease. The children had come to live temporarily in Hullett (now part of the Municipality of Central Huron) with their parents during the flax harvest, but their permanent home was reported as ‘Muncey Reserve.’ Indigenous families from Southwestern Ontario reserve communities, including those on the shore of the Thames River south of London and also Saugeen First Nation to the north, were a crucial labour force for annual flax harvests in the early twentieth century. Entire families moved seasonally to pull flax for Huron growers; they worked and lived in close contact with each other, camping alongside their worksites.

The sick children belonged to a group of about 15 families living in tents roughly six miles from Clinton when the infantile paralysis struck-eventually infecting two five-year-olds and a two-year-old. A local Blyth doctor treated the first cases and told the area newspapers that the farm workers’ living situation presented a challenge for protecting the lives of the other 23 children in the camp: “Isolation and quarantine, so necessary for the treatment of infantile paralysis, are something hard to enforce in any Indian reservation or encampment…We are doing what we can to prevent any spread of the disease, and watching for further symptoms, but it is next to impossible to enforce the requisite isolation.” The vast majority of poliovirus cases are completely asymptomatic. The disease can spread through direct contact or via contamination by human waste.

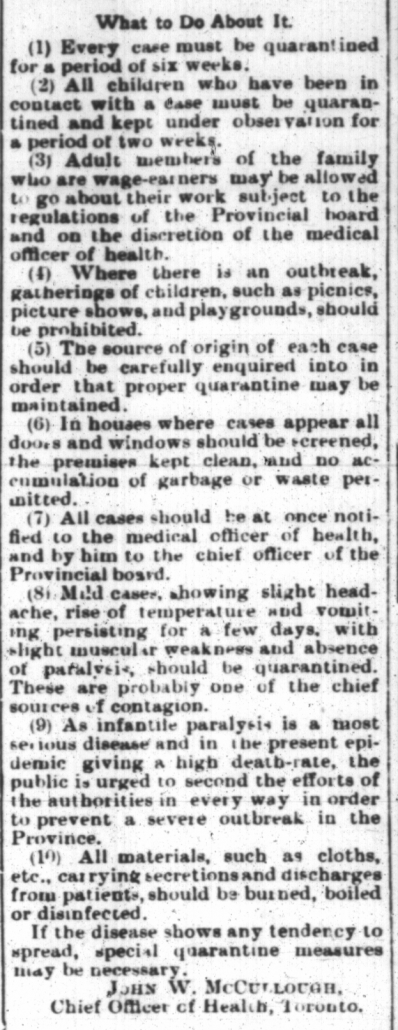

From the Wingham Advance, August 31st, 1916.

For one of the five-year-olds, the virus was tragically fatal on August 25th, but the other two children soon appeared to be recovering. Local newspapers did not identify any of the camp members by name, but a death registration reveals that the little girl who lost her life was Annie Corneolus, the five-year-old daughter of Abram and Elizabeth. She was ill only one day, but the polio had caused lethal ‘paralysis of respiration.’ Her birthplace is recorded as Oneida Reserve (Oneida Nation of the Thames). Annie’s burial took place at Burns Cemetery, Hullett. Local health officials separated the families with sick children from the rest of their neighbours and they proceeded to quarantine at a farmer’s house on the 11th Concession. School Section # 11 at Londesborough cancelled classes for all students as a precaution.

Fortunately, their quarantine appeared successful and there were no further cases reported. The Clinton New Era announced that “the infantile paralysis scare in Hullett Township has pretty well blown over.” When health authorities lifted quarantine the families impacted returned to their reserve community, and the rest of the camp moved on to Blyth to continue their flax-pulling work. The Huron newspapers make no mention of whether or not the surviving children suffered any long-term health effects. Later reports listed the total number of province-wide infantile paralysis cases at 64 for July and August of 1916, with 8 resulting deaths–meaning that 25% of those total polio deaths occurred in Huron County.

From the Signal (Goderich), July 20th, 1916.

There is no cure for polio, but the Salk vaccine of 1955 would eventually be effective and widely used to prevent the disease; after continuous deadly outbreaks throughout the first half of the twentieth century, childhood vaccinations have eradicated polio in Canada.

The living and working conditions of temporary farm workers in 1916 would have made following advice about precautionary hygiene and social distancing almost impossible to follow-and many people in Canada are facing those same challenges today, without equal housing or opportunities to practice self-isolation under novel coronavirus. Although the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic is not the same as polio, the reality that Indigenous communities continue to be disproportionately impacted by pandemics, and that temporary and migrant workers are at a higher risk because of a lack of resources and opportunities to safely distance is absolutely precedented.

More Info about the history of polio in Canada: https://www.cpha.ca/story-polio

*Note: I wrote this blog post using contemporary newspaper accounts including the Wingham Times, The Wingham Advance, The Lucknow Sentinel, The Clinton New Era, The Clinton News-Record, the Signal (Goderich) and others, all accessed from Huron’s free historical newspaper database: https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers/ Annie’s death documentation was accessed via Ancestry.ca (Archives of Ontario; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Collection: MS935; Reel: 220). All of these accounts were written from a settler point of view (as is my own), and the newspapers did not include the voices or even the names of the community members impacted. If you have any further information you’d like to share about this outbreak or similar outbreaks in the past contact museum@huroncounty.ca.

by Sinead Cox | Mar 30, 2020 | Artefacts, Collection highlights, Exhibits, For Teachers and Students, Uncategorized

Huron County Museum: Virtual Permanent Galleries

The Huron County Museum’s virtual exhibits grant a close-up glimpse of select artifacts on permanent display in our galleries, as well as information that you can’t guess with just a look. The featured objects represent a small sampling of the thousands of artifacts in the museum’s collection. Updating the online exhibits is an ongoing project; in the future, student employees will be refreshing the images and providing even more information. These exhibits are also available via ipads onsite when the museum is open.

Huron County Main Street

Our Main Street features real storefronts and objects from across the county of Huron.

Click the storefront names to step inside and see artifact highlights!

Military Gallery

Click the titles below to see archival documents and more related to Huron County and the First World War.

Huron County Museum Feature Gallery: Virtual Exhibits

The Huron County Museum rotates exhibits of special interest through the year in our Feature Galleries. Click to explore past temporary exhibits that you may have missed or want to rediscover.

by Sinead Cox | Nov 11, 2017 | Exhibits, Investigating Huron County History

From Nov. 21st, 2017 to March 2018, the museum’s temporary Hot off the Press: Seen in the County Papers exhibit will look behind the headlines to the men, women and changing technologies that have brought Huron’s weekly papers to press for over almost 175 years. In this Remembrance Day post, Sinead Cox, Curator of Engagement & Dialogue and curator of the upcoming exhibit, examines the life of one Huron newsman who was also a veteran of the First World War, and follows the story of his return from service via mentions in the local weekly papers.

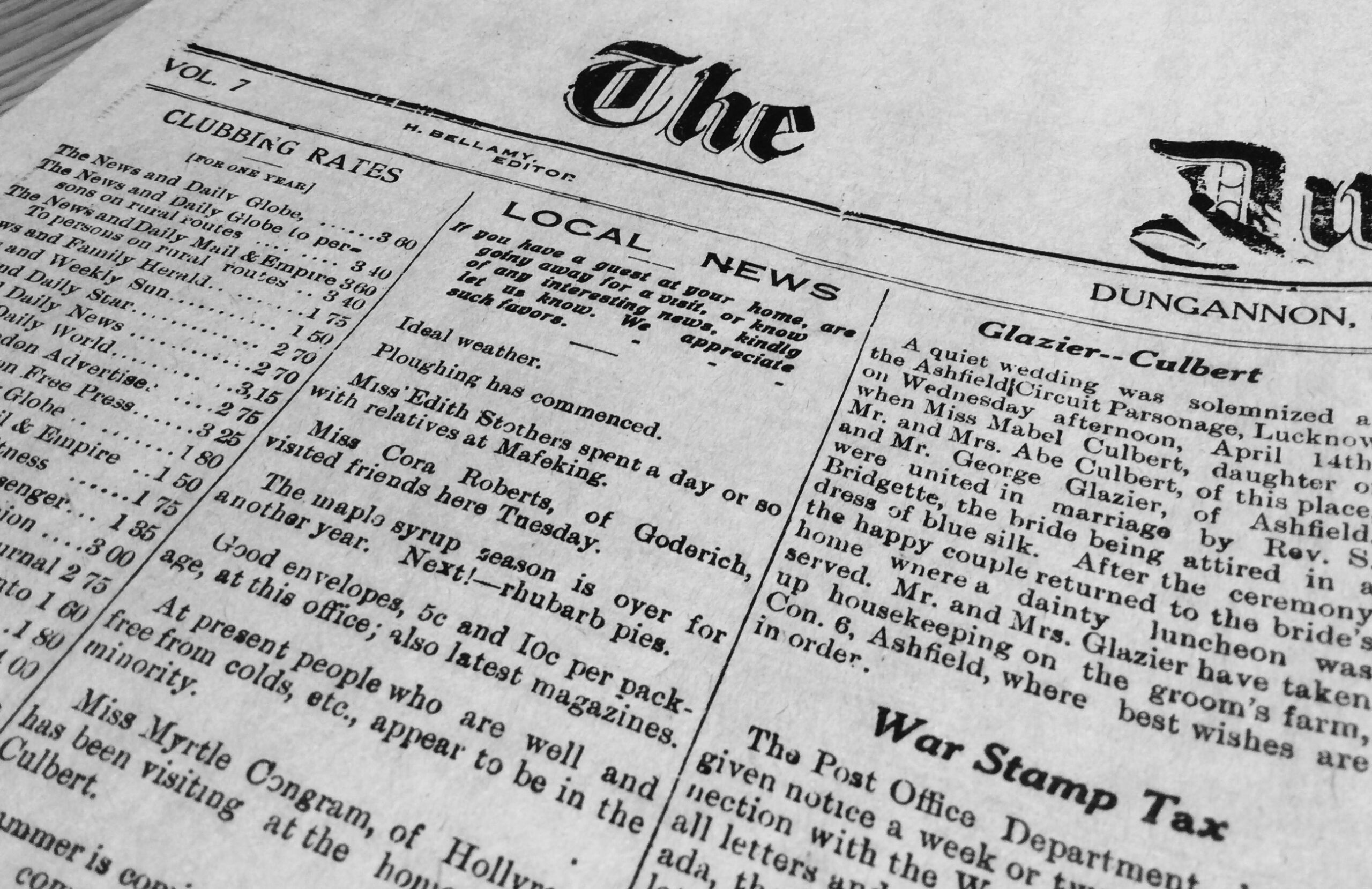

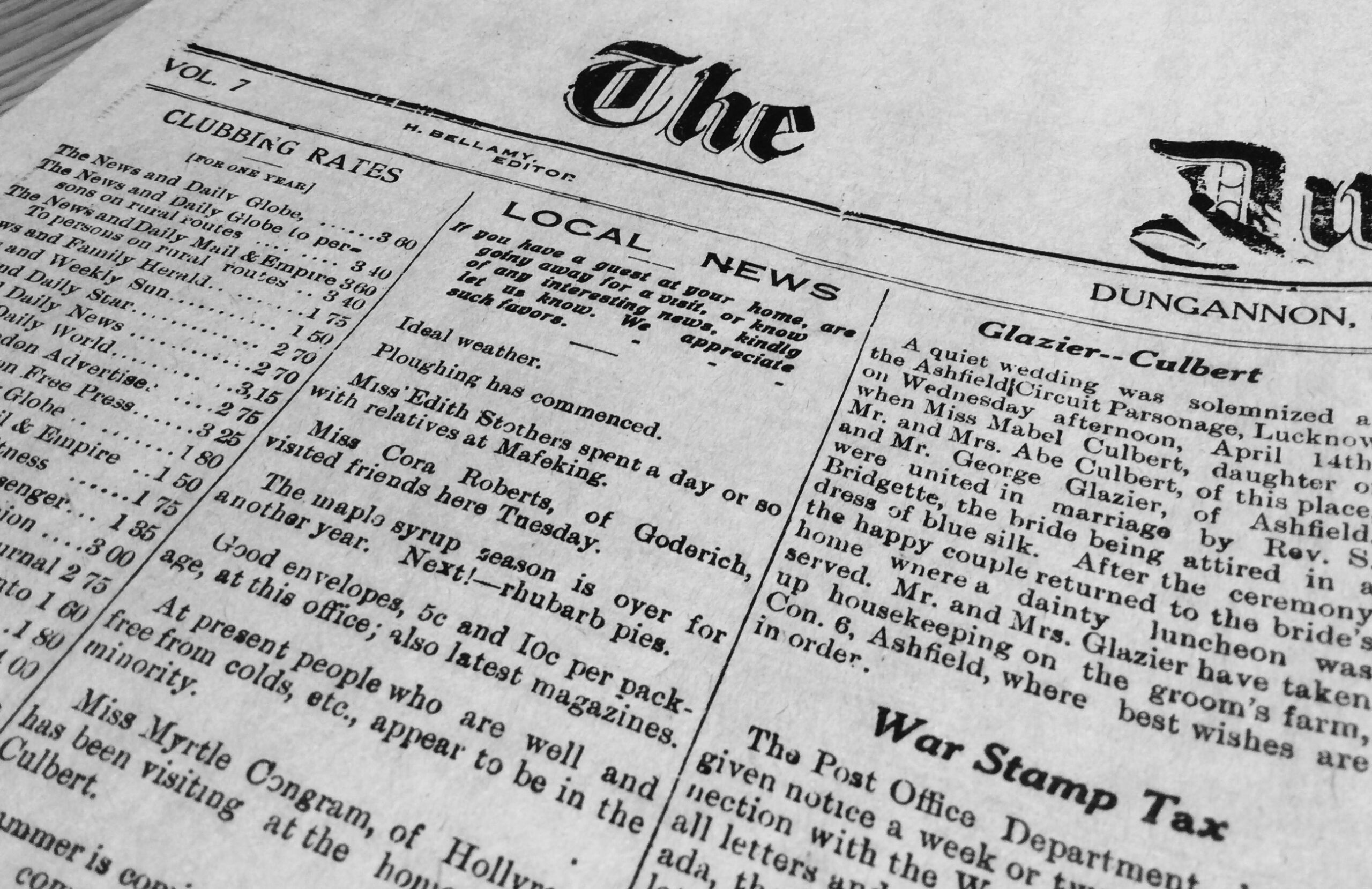

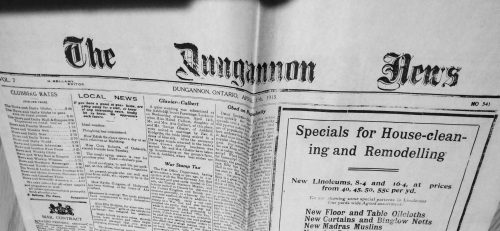

The Dungannon News, 1915-04-15

From my research into Huron County’s newspapers, it’s clear that a lot of effort, long hours and personal sacrifice often went into putting a paper to press and ensuring the latest edition reached local subscribers’ doorsteps on time. There were few excuses that could justify a late paper on the part of its proprietors: perhaps broken equipment, the precedence of a contracted print job (ie printing election ballots), adverse weather, public holidays, or even the rare editor’s vacation. One of the most notable reasons to stop the presses, however, occurred in 1916 when The Dungannon News ceased publication entirely because its editor enlisted to serve overseas with Huron’s 161st Battalion.

Pte. Bellamy’s attestation paper. You can access his full personnel file at: http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/

Born in 1891 in Blanshard Township, Perth County, Charles Arthur Harold “Harry” Bellamy had moved to Huron by 1908 when his step-father, Leslie S. Palmer–a former staffer at the St. Marys Journal and owner of the Wroxeter Star–founded The Dungannon News. His sisters, Amelia and Luella Bellamy, also worked locally as operators for the Dungannon telephone office. When his mother and step-father moved to Goderich in 1914, Harry became both editor and publisher of the News while still in his early twenties.

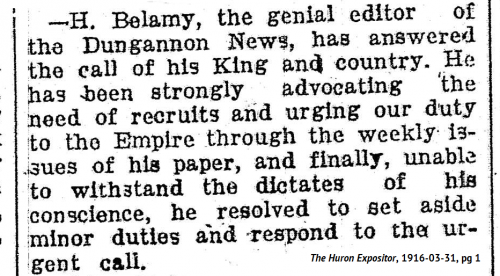

As editor, H. Bellamy strongly supported Canada’s involvement in the Great War within the pages of his publication, and by March of 1916 had decided to enlist himself. At only 24 years old, and a newlywed of less than two years with his wife, Annie Pentland of Ashfield Township, Editor Bellamy signed up to serve with the Canadian Expeditionary Forces at Goderich. With the departure of its proprietor, The Dungannon News merged with Goderich’s Tory weekly, The Star, and the newsman became the news as fellow editors praised Harry Bellamy’s decision in the columns of their papers.

The Wingham Advance, 1916-03-23, pg 5

Assigned to the 58th Battalion in Europe, Pte. Bellamy appeared once again in the pages of the local weeklies through his letters from the front. Stationed “somewhere in France” on Dec. 26th, 1916, Harry wrote to his friend F. Ross of how his “three or four days’ trench life” had begun with digging out a trench collapsed by shell-fire; he had become accustomed to ducking down for enemy fire “no matter how deep the mud and water is.” While evading sniper bullets in a no man’s land crater, Bellamy says he pretended he was at home, practicing with friends at the Dungannon Rifle Association.

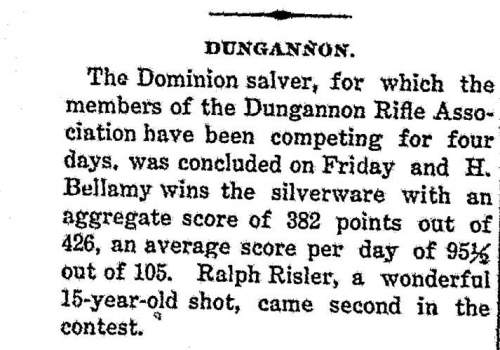

The Wingham Times, 1911-12-28, pg 4

Imagining away the conditions he described would have no doubt been difficult: “We sleep and rest in the dugouts, which are twenty to twenty-five feet underground. After splashing, crawling and wading through trench mud for hours at a time, we find it quite a relief to get down in these underground quarters.” On Christmas day he witnessed “a fierce bombardment…It was a magnificent sight to see the green and red flames and the shells with their tails of fire flying…The noise and din of the various kinds of explosives in use was deafening.” In the same letter, which Goderich’s The Signal printed on its front page, he claimed that the brutal lifestyle had not dampened the soldiers’ spirits: “we never worry over here. We content ourselves with singing, ‘Pack all your troubles in your old kit bag and smile, smile, smile.’”

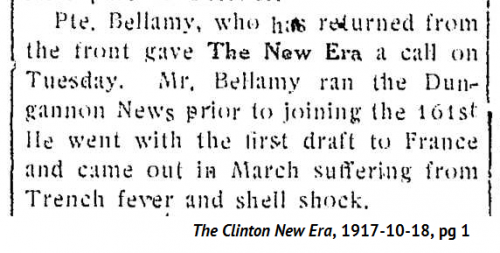

Although he was writing for the local papers, Pte. Bellamy was not able to regularly read them in Europe, and complained that the delays in mail also prevented him from keeping up-to-date with happenings in Huron County. According to his service records, a year after he had enlisted at Goderich, Harry fell ill with trench fever–an infectious disease carried by body lice. He left France for treatment in the U.K., and after complaining of pain in his limbs at York County Hospital, doctors at the King’s Red Cross Canadian Convalescent diagnosed him with myalgia (joint pain) and an abnormally fast pulse.

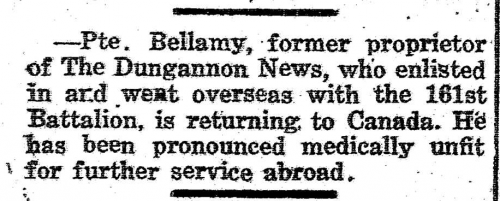

The Huron Expositor, 1917-10-12, pg 5

In articles subsequently written for the Goderich Star, Pte. Bellamy did not detail his failing health, instead returning to his pen to share his experiences sightseeing on leave in Scotland and Ireland in August, 1917. Ever a committed imperialist, he enjoyed witnessing the Glorious Twelfth celebrations in Belfast, but reported caring less for his time in southern Ireland, since “there is no love lost between those in khaki and the Irish rebels.” He felt wistfulness upon the end of his holiday, but Pte. Bellamy’s belief in the righteousness of the war had not wavered; he used his Star articles to rally homefront sentiments against peace until the enemy could be decisively defeated: “let…every one of us, as Canadians, recapture the heroic mood in which we entered the war.”

The Signal, 1917-12-06, pg 6

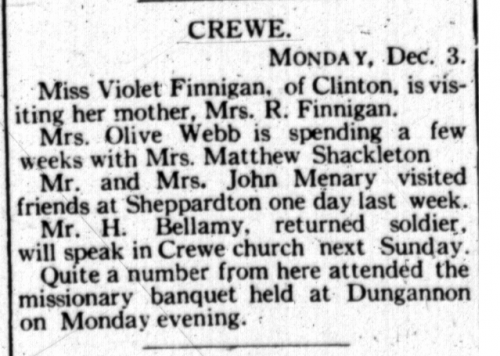

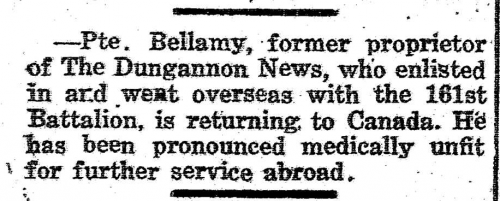

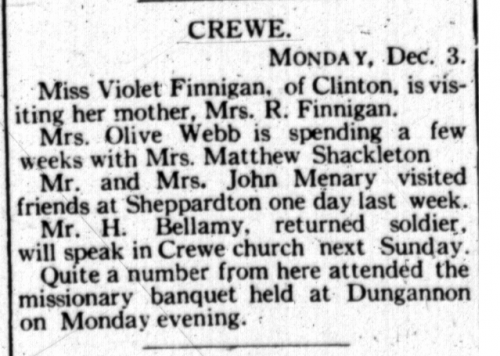

Unable to resume his duties as a soldier, Pte. Bellamy returned to Canada, where in addition to his persistent trench fever, he received a diagnosis of neurasthenia–a contemporary term broadly used for nervous disorders. After his homecoming, he reappeared frequently in the local news columns, usually receiving mention for promoting the war effort at local patriotic events or canvassing for Victory Loans.

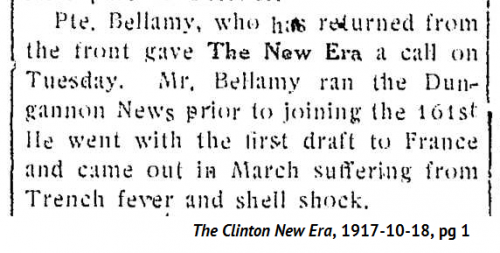

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

In April 1918, a medical board at Guelph honourably discharged Harry as medically unfit due to illness contracted on active service. His records list a ‘nervous debility,’ as well as trench fever as the causes for his dismissal, and note that “this man would not be able to do more than one quarter of a days [sic] work.” The listed symptoms in his medical records include dizzy spells, light headedness, restlessness, hand tremors, headaches, and an irregular heartbeat. The Board determined that the probable duration of his debility was “impossible to state.”

The Wingham Advance, 1918-06-13, pg 5

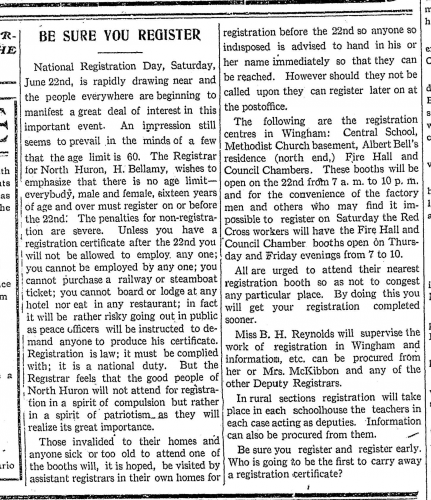

Despite experts’ doubts about his ability to cope with a full-time job, Harry received a temporary government position as North Huron’s Registrar for 1918’s National Registration Day effort. The federal government intended this wartime “man and woman power census” to identify available labour forces for the homefront and overseas by requiring all Canadians over sixteen to register.

Nothing in the newspapers suggests that Harry Bellamy returned to printing or publishing on a full-time basis in Dungannon. After the war was over in 1919, Ashfield accepted Harry’s application for the township’s annual printing contract with special consideration to him as a “returned soldier,” but according to an item in The Wingham Advance he later declined the work for the pay offered. There was evidently a vocation that Harry Bellamy now felt more passionately for than journalism, because in May of that year the New Era records that he moved to Toronto to accept a bureaucratic position “in connection with the re-establishment of soldiers.” In 1921, Harry ultimately sold The Dungannon News printing equipment to a buyer from Meaford, and he and wife Annie settled permanently in Toronto.They didn’t entirely disappear from print, however, as local news columns over the next decade continued to note the couple’s visits to friends and family in Huron County.

The Signal, 1921-3-31, pg 4

Following Pte. Bellamy’s story via short items in the county papers certainly does not provide a full picture of his life, nor the toll of his experiences in the trenches of France. The information gleaned, though, does speak to the value of these local weeklies as historical resources, and that comparing them against other records–in this case Pte. Bellamy’s military personnel files– can help us to read between the lines. It’s also a pertinent reminder that both historical and news sources are better understood if we know a little about the context and perspective of the people creating them. What emerged in this case was the story of a man whose politics on the page never changed, whose service to the Canadian government continued beyond the battlefield and loyalty to the British empire never faltered, but who nevertheless could not quite pack the personal consequences of war away in an “old kit bag and smile, smile, smile.”

Hot off the Press: Seen in the County Papers opens Nov. 21st at the Huron County Museum! Visit the exhibit to learn more about the stories behind Huron’s historic headlines. You can browse the newspaper collection from the comfort of home at dev.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers. Information for this blog post came from Huron County’s digitized newspapers and Library and Archives Canada’s digitized service records.

by Sinead Cox | May 9, 2016 | Exhibits, Investigating Huron County History

Not every new neighbor throughout Huron County’s history has been welcomed universally by the community; some have faced prejudice and discrimination. Education and Programming Assistant Sinead Cox, who led research for the current Stories of Immigration and Migration Exhibit, writes about the hostility and misconceptions faced by one of these migrant groups.

In 1895, an anonymous East Wawanosh farmer called for an end to the immigration of a despised immigrant group to Canada. Suspected of being untrustworthy and even violent, the farmer lamented to the Daily Mail & Empire that these migrants were “a curse to the country, as a rule.” The dangerous group he was referring to were young, poor, British children.

Article from the Daily Mail and Empire, July 23, 1895.

Between the 1860s and 1930s, U.K. charity homes sent thousands of urban boys and girls commonly known as ‘home children’ to Australia, South Africa and Canada as farm labourers or domestic servants. These young migrants feared as a threat to the moral character of Canadian society had little say in leaving the country of their birth, or their estrangement from any family they might have still had there. In 2010 the U.K. government officially apologized for the forced emigration of these children, which often involved what charity home founder Dr. Thomas Barnardo termed ‘philanthropic abduction’: sending poor children across the ocean without the knowledge of their still-living parents, siblings or guardians. Without knowing the children might be sent half a world away, caretakers had often placed them in the homes because of a sudden lack of funds to properly care for them, sometimes due to unemployment, insufficient wages, or the death or illness of a parent.

Between the 1860s and 1930s, U.K. charity homes sent thousands of urban boys and girls commonly known as ‘home children’ to Australia, South Africa and Canada as farm labourers or domestic servants. These young migrants feared as a threat to the moral character of Canadian society had little say in leaving the country of their birth, or their estrangement from any family they might have still had there. In 2010 the U.K. government officially apologized for the forced emigration of these children, which often involved what charity home founder Dr. Thomas Barnardo termed ‘philanthropic abduction’: sending poor children across the ocean without the knowledge of their still-living parents, siblings or guardians. Without knowing the children might be sent half a world away, caretakers had often placed them in the homes because of a sudden lack of funds to properly care for them, sometimes due to unemployment, insufficient wages, or the death or illness of a parent.

Child Migration was intended to ease urban poverty in the British Isles and agricultural labour shortages in the colonies.Once in Canada, the children were expected to work and attend school, and received infrequent inspection visits to monitor their welfare. Canadian employers tended to treat the young immigrants as hired hands, rather than adopted family members, and many changed homes frequently. Although rural Canada might have provided more employment opportunities than urban England, living among strangers often left the children vulnerable to abuse, neglect or overwork with tragic results. In 1923, Huron County farmer John Benson Cox was convicted of abusing Charles Bulpitt, the sixteen-year-old ‘home boy’ working for him, after Charles died by suicide in his care.

Excerpt from The Montreal Gazette, Feb. 8, 1924

At the time, some Canadians welcomed the cheap farm labour provided by the child migrants, while others feared that these lower class ‘waifs and strays’ must be ‘the offspring of criminals and tramps,’ and therefore inherently bad and dangerous to God-fearing citizens of the Dominion. In Canadian author L.M. Montgomery’s beloved classic, Anne of Green Gables, character Marilla Cuthbert famously dismissed the possibility of welcoming a child from the U.K. charity homes to Green Gables:

At first Matthew suggested getting a Barnardo boy. But I said ‘no’ flat to that. They may be all right—I’m not saying they’re not—but no London Street Arabs for me…I’ll feel easier in my mind and sleep sounder at nights if we get a born Canadian.

Public fears about these ‘street Arabs’ were no doubt influenced by the widespread popularity of the pseudoscientific practice of eugenics at the turn of the twentieth century. Eugenicists erroneously believed that some people were genetically superior to others, and these good traits would be diluted and society damaged by mixing with groups having supposedly inferior genes, including the mentally ill or developmentally challenged. Eugenicist policies were widely touted by many prominent Canadians, including philanthropists and legislators.

At an 1894 federal Select Standing Committee on Agriculture and Colonisation, East Huron Member of Parliament Dr. Peter Macdonald spoke against government subsidies for the immigration of ‘home children.’ His concerns were not based on the welfare and safety of the young immigrants, but on the potential ill effect their introduction would have on Canadian society, particularly because of their eventual intermarriage with existing Canadian settler families:

August 13, 1906 Globe and Mail article describing the arrival of 200 Barnardo Home boys, which included Bernard Brown.

Those children are dumped on Canadian soil, who, in my opinion, should not be allowed to come here at all. It is just the same as if garbage were thrown into your backyard and allowed to remain there. We find from the testimony of disinterested parties in this country, that a large number of these children have turned out bad, and are poisoning our population by intermarrying with them…I think myself this committee should unite in an expression of opinion that no such $2 a head should be paid by this government to bring such a refuse of the old country civilization, and pour it in here among our people. We take more means to purify our cattle than to purify our population?

Despite objectors like Macdonald, charity homes sent more than 100,000 British children to Canada, and today likely millions of Canadians are the descendants of these children who, despite the hardships of forced migration and separation from loved ones in childhood, often survived and persevered to earn a living and raise a family of their own. Although they had essentially been exiled by the British Empire, a huge proportion of ‘home boys’ also later volunteered to serve in the first and second world wars as young men.

Bernard Brown in his military uniform. He enlisted with the 161st Regiment of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces in January 1916. Photo courtesy of Brown Family.

One such child migrant, Bernard Brown (1896-1918), came to Huron County at ten years old. Bernard’s journey from a poor, struggling family in Northern Ireland that could not afford to feed all of their children, to an English charity home, to a Tuckersmith Township farm, and finally to the battlefields of France, was featured in the Huron County Museum’s Stories of Immigration and Migration, a temporary exhibit that tracks the narratives of seven families who came to our county between 1840 and 2007.

Similarly to many refugee families today, child migrants like Bernard Brown did not choose Huron County as their ultimate destination, but were matched there. When Bernard was placed with a couple in Tuckersmith, he was separated from his younger brother Edward whom Barnardo’s sent to Ripley, Bruce County. In hindsight, cases of mistreatment and neglect indicate that these young people an ocean away from loved ones, unable to return home and at the mercy of strangers, ultimately had much more to fear from Canadians than Canadians had to fear from them. The eventual success and resilience of those who survived childhood and the millions among us who can today claim a ‘home child’ as an ancestor are a testament to the fact that although the U.K and Canadian governments may have tragically failed them, the ‘home children’ contributed immeasurably to our communities rather than ‘poisoned’ them.

To find out more about the experience of one home child in Huron County, see Bernard’s story when you visit Stories of Immigration and Migration, on display in the Temporary Gallery at the Huron County Museum until October 15th, 2016. Are you descended from a home child? Share your family’s story with us tagged #homeinhuron or add it to the visitor-submitted stories in the exhibit.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

Other brief news items hint, however, that although Pte. Harry Bellamy had returned home to Dungannon, he had not left the trenches entirely behind. He received treatment at a London hospital in early 1918 according to The Signal. Following a social call from former editor Bellamy, the Clinton New Era classified his nervous illness as ‘shell shock’: a mental and emotional disorder common to returning soldiers, which today would probably be understood as post traumatic stress disorder.

Between the 1860s and 1930s, U.K. charity homes sent thousands of urban boys and girls commonly known as ‘home children’ to Australia, South Africa and Canada as farm labourers or domestic servants. These young migrants feared as a threat to the moral character of Canadian society had little say in leaving the country of their birth, or their estrangement from any family they might have still had there. In 2010 the U.K. government officially apologized for the forced emigration of these children, which often involved what charity home founder Dr. Thomas Barnardo termed ‘philanthropic abduction’: sending poor children across the ocean without the knowledge of their still-living parents, siblings or guardians. Without knowing the children might be sent half a world away, caretakers had often placed them in the homes because of a sudden lack of funds to properly care for them, sometimes due to unemployment, insufficient wages, or the death or illness of a parent.

Between the 1860s and 1930s, U.K. charity homes sent thousands of urban boys and girls commonly known as ‘home children’ to Australia, South Africa and Canada as farm labourers or domestic servants. These young migrants feared as a threat to the moral character of Canadian society had little say in leaving the country of their birth, or their estrangement from any family they might have still had there. In 2010 the U.K. government officially apologized for the forced emigration of these children, which often involved what charity home founder Dr. Thomas Barnardo termed ‘philanthropic abduction’: sending poor children across the ocean without the knowledge of their still-living parents, siblings or guardians. Without knowing the children might be sent half a world away, caretakers had often placed them in the homes because of a sudden lack of funds to properly care for them, sometimes due to unemployment, insufficient wages, or the death or illness of a parent.