by Sinead Cox | Jun 4, 2020 | Investigating Huron County History

Curator of Engagement and Dialogue Sinead Cox shares the story of a historical quarantine in the summer of 1916.

Although you may have heard (to the point of cliché) that we are living in ‘unprecedented times’ during today’s COVID-19 pandemic, communities across Huron County have seen quarantines and the temporary closure of schools and businesses before. Although usually on a much smaller and localized scale, these actions in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were in response to contagious illnesses that included influenza, measles, diphtheria, scarlet fever, smallpox, whooping cough and typhoid among others.

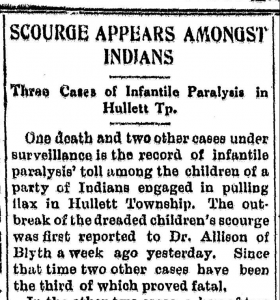

From The Brussels Post, July 27th, 1916.

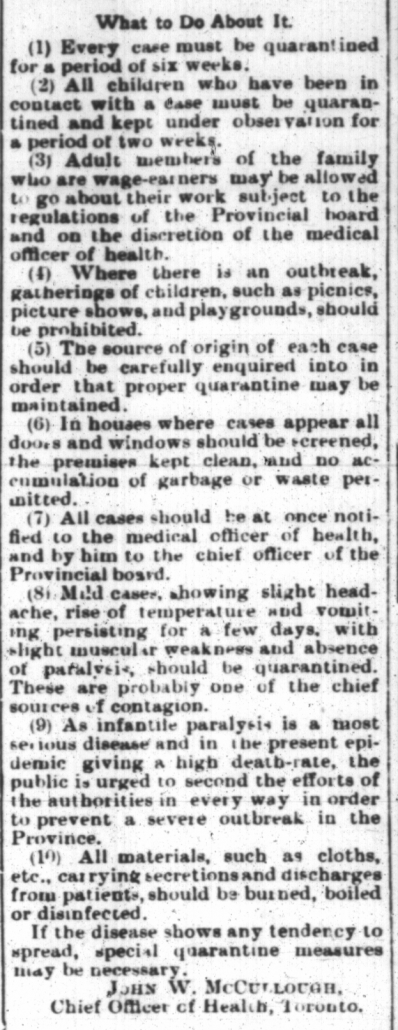

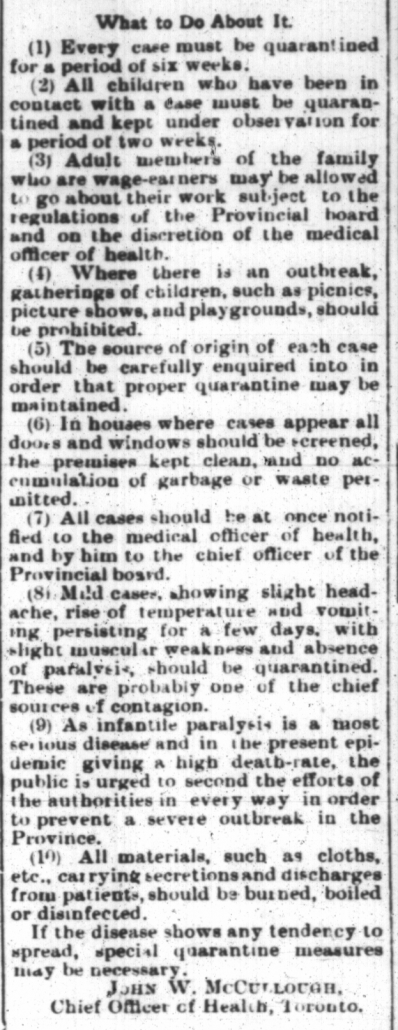

In 1916 an outbreak of infantile paralysis (polio or poliomyelitis) hit North America. The poliovirus is most dangerous to children under five years of age and in serious cases can cause permanent and debilitating nerve and muscle damage to survivors if non-fatal. The 1916 epidemic was particularly devastating in New York and then appeared in Canadian cities like Montreal before eventually arriving in southern Ontario. In Ontario, the provincial Medical Board of Health enacted quarantine regulations and required doctors to report all cases or face prosecution.

The outbreak had reached Huron County by July, when a fourteen-month-old girl in Varna died: only the second fatal case confirmed in Ontario up to that point. Panic hit the next month when three young children in Hullett Township contracted the much-feared disease. The children had come to live temporarily in Hullett (now part of the Municipality of Central Huron) with their parents during the flax harvest, but their permanent home was reported as ‘Muncey Reserve.’ Indigenous families from Southwestern Ontario reserve communities, including those on the shore of the Thames River south of London and also Saugeen First Nation to the north, were a crucial labour force for annual flax harvests in the early twentieth century. Entire families moved seasonally to pull flax for Huron growers; they worked and lived in close contact with each other, camping alongside their worksites.

The sick children belonged to a group of about 15 families living in tents roughly six miles from Clinton when the infantile paralysis struck-eventually infecting two five-year-olds and a two-year-old. A local Blyth doctor treated the first cases and told the area newspapers that the farm workers’ living situation presented a challenge for protecting the lives of the other 23 children in the camp: “Isolation and quarantine, so necessary for the treatment of infantile paralysis, are something hard to enforce in any Indian reservation or encampment…We are doing what we can to prevent any spread of the disease, and watching for further symptoms, but it is next to impossible to enforce the requisite isolation.” The vast majority of poliovirus cases are completely asymptomatic. The disease can spread through direct contact or via contamination by human waste.

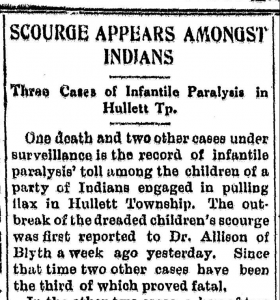

From the Wingham Advance, August 31st, 1916.

For one of the five-year-olds, the virus was tragically fatal on August 25th, but the other two children soon appeared to be recovering. Local newspapers did not identify any of the camp members by name, but a death registration reveals that the little girl who lost her life was Annie Corneolus, the five-year-old daughter of Abram and Elizabeth. She was ill only one day, but the polio had caused lethal ‘paralysis of respiration.’ Her birthplace is recorded as Oneida Reserve (Oneida Nation of the Thames). Annie’s burial took place at Burns Cemetery, Hullett. Local health officials separated the families with sick children from the rest of their neighbours and they proceeded to quarantine at a farmer’s house on the 11th Concession. School Section # 11 at Londesborough cancelled classes for all students as a precaution.

Fortunately, their quarantine appeared successful and there were no further cases reported. The Clinton New Era announced that “the infantile paralysis scare in Hullett Township has pretty well blown over.” When health authorities lifted quarantine the families impacted returned to their reserve community, and the rest of the camp moved on to Blyth to continue their flax-pulling work. The Huron newspapers make no mention of whether or not the surviving children suffered any long-term health effects. Later reports listed the total number of province-wide infantile paralysis cases at 64 for July and August of 1916, with 8 resulting deaths–meaning that 25% of those total polio deaths occurred in Huron County.

From the Signal (Goderich), July 20th, 1916.

There is no cure for polio, but the Salk vaccine of 1955 would eventually be effective and widely used to prevent the disease; after continuous deadly outbreaks throughout the first half of the twentieth century, childhood vaccinations have eradicated polio in Canada.

The living and working conditions of temporary farm workers in 1916 would have made following advice about precautionary hygiene and social distancing almost impossible to follow-and many people in Canada are facing those same challenges today, without equal housing or opportunities to practice self-isolation under novel coronavirus. Although the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic is not the same as polio, the reality that Indigenous communities continue to be disproportionately impacted by pandemics, and that temporary and migrant workers are at a higher risk because of a lack of resources and opportunities to safely distance is absolutely precedented.

More Info about the history of polio in Canada: https://www.cpha.ca/story-polio

*Note: I wrote this blog post using contemporary newspaper accounts including the Wingham Times, The Wingham Advance, The Lucknow Sentinel, The Clinton New Era, The Clinton News-Record, the Signal (Goderich) and others, all accessed from Huron’s free historical newspaper database: https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers/ Annie’s death documentation was accessed via Ancestry.ca (Archives of Ontario; Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Collection: MS935; Reel: 220). All of these accounts were written from a settler point of view (as is my own), and the newspapers did not include the voices or even the names of the community members impacted. If you have any further information you’d like to share about this outbreak or similar outbreaks in the past contact museum@huroncounty.ca.

by Sinead Cox | May 7, 2020 | Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

In this two-part series, Curator of Engagement & Dialogue Sinead Cox illuminates how the Second World War impacted Huron County in unexpected ways at home, and even entered the walls of the Huron Historic Gaol. Click for Part Two, and the strange tale of how Dutch sailors became wartime prisoners in Huron’s jail.

During the Second World War, Canada revived the War Measures Act: a statute from the First World War that granted the federal government extended authority, including controlling and eliminating perceived homegrown threats. The Defence of Canada Regulations implemented on September 3, 1939 increased censorship; banned particular cultural, political and religious groups outright; gave extended detainment powers to the Ministry of Justice and limited free expression. In Huron County, far from any overseas battlefields, these changes to law and order would bring the Second World War closer to home.

Regulations required Italian and German-born Canadians naturalized as citizens after 1929 (expanded to 1922 the following year) to formally register as ‘enemy aliens’ and report once a month. In Huron County, jail Governor James B. Reynolds accepted the appointment of ‘Registrar of Enemy Aliens’ in the autumn of 1939, and the registration office was to operate from the jail in Goderich. There were also offices in Wingham, Seaforth and Exeter managed by the local chief constables of the police force.

Regulations required Italian and German-born Canadians naturalized as citizens after 1929 (expanded to 1922 the following year) to formally register as ‘enemy aliens’ and report once a month. In Huron County, jail Governor James B. Reynolds accepted the appointment of ‘Registrar of Enemy Aliens’ in the autumn of 1939, and the registration office was to operate from the jail in Goderich. There were also offices in Wingham, Seaforth and Exeter managed by the local chief constables of the police force.

In addition to its novel function as the alien registration office, the Huron Jail also housed any prisoners charged criminally under the temporary wartime laws. Inmate records from the time period of the Second World War cannot be accessed, but Reynolds’ annual reports submitted to Huron County Council indicate that one local prisoner was committed to jail under the ‘Defence of Canada Act’ in 1939, and there were an additional four such inmates in 1940. The most common charges landing inmates behind bars during those years were still typical for the county: thefts, traffic violations, vagrancy and violations of the Liquor Control Act (Huron County being a ‘dry’ county).

Frank Edward Eickemier, the lone individual jailed under the War Measures Act’s Defence of Canada regulations in 1939, was no ‘alien,’ but the Canadian-born son of a farm family in neighbouring Perth County. Nineteen-year-old Eickemier pled guilty to ‘seditious utterances’ spoken during the Seaforth Fall Fair, and received a fine of $200 and thirty days in jail (plus an additional six months if he defaulted on the fine). The same month the Defence of Canada regulations took effect, Eickemier had publicly proclaimed that Adolph Hitler’s Nazi Germany was undefeatable, and that if it were possible to travel to Europe he would join the German military. He fled the scene when constables arrived, but was soon pursued and arrested for “statements likely to cause disaffection to His Majesty [King George VI] or interfere with the success of His Majesty’s forces.” His crime was not necessarily his political views, but his disloyalty. The prosecuting Crown Attorney conceded, “A man in this country is entitled to his own opinion, but when a country is at war you can’t go around making statements like that.”

Bruce County law enforcement prosecuted a similar case in July of 1940 against Martin Duckhorn, a Mildmay-area farm worker employed in Howick Township, and alleged Nazi sympathizer. Duckhorn had been born in Germany, and as an ‘enemy alien’ his rights were essentially suspended under the War Measures Act, and he thus received an even harsher punishment than Eickemier: to be “detained in an Ontario internment camp for the duration of the war.”

Huron County Courthouse & Courthouse Square, Goderich c1941. A991.0051.005

In July of 1940, the Canadian wartime restrictions extended to making membership in the Jehovah’s Witnesses illegal. The inmates recorded as jailed under the ‘Defence of Canada Act’ in Huron that year were likely all observers of that faith, which holds a refusal to bear arms as one its tenets, as well as discouraging patriotic behaviours. That summer, two Jehovah’s Witnesses arrested at Bluevale and brought to jail at Goderich ultimately received fines of $10 or 13 days in jail for having church publications in their possession. Four others accused of visiting Goderich Township homes to discourage the occupants from taking “any side in the war” had their charges dismissed—due to a lack of witnesses. In 1943, the RCMP and provincial police collaborated to arrest another three Jehovah’s Witnesses in Goderich Township for refusing to submit to medical examinations or report their current addresses (therefore avoiding possible conscription); the courts sentenced the three charged to twenty-one days in the jail, afterwards to be escorted by police to “the nearest mobilization centre.”

By August of 1940, an item in the Exeter Times-Advocate claimed that RCMP officers were present in the area to ‘look up’ those individuals who had failed to comply with the law and promptly register as enemy aliens. A few weeks later, the first Huron County resident fined for his failure to register appeared in Police Court. The ‘enemy alien’ was Charles Keller, a 72-year-old Hay Township farmer who had lived in Canada for 58 years, emigrating from Germany as a teenager in 1882. According to his 1949 obituary in the Zurich Herald, Keller was the father of nine surviving children, a member of the local Lutheran church, and had retired to Dashwood around 1929. His punishment for neglecting to register was not jail time, but the fine of $10 and costs (about $172.00 today according to the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator).

Although incidences of prosecution under the ‘Defense of Canada Act’ in Huron County were few, the increased scrutiny and restrictions would have been felt in the wider community, especially for those minority groups and conscientious objectors directly impacted. Huron had a notable number of families with German origins, especially in areas like Hay Township where you can still see the tombstones of many early settlers written in German. The Judge who sentenced Frank Edward Eickemier for his public support of the Nazi regime in 1939 made a point of accusing him of casting a ‘slur’ on his ‘people’ and all German Canadians: the actions of the individual conflated with a much larger and diverse German community by a representative of the law. His case indicates that pro-fascist and pro-Nazi sentiment certainly did exist close to home, but a person’s place of birth or their religion was not the crucial evidence that could define who was or was not an ‘enemy.’

Next Week: Click for Part Two, and the strange tale of how stranded Dutch sailors ended up prisoners in the Huron County Jail during the Second World War.

*A note on spelling: Jail & gaol are alternative spellings of the same word, pronounced identically. Both spellings were used throughout the history of the Huron Historic Gaol fairly interchangeably. Although as a historic site the Huron Historic Gaol uses the ‘G’ spelling more common to the nineteenth century, for this article I have chosen to employ the ‘J’ spelling that appeared more consistently in the 1940s.

Further Reading

The War Measures Act via the Canadian Encyclopedia

Sources

Research for this blog post was conducted largely via Huron’s digitized historical newspapers.

“Faces Trial on Charge of Making Disloyal Remark.” Seaforth News, September 28, 1939.

“German Sympathizer Interned.” The Wingham-Advance Times, July 25, 1940.

“In Police Court.” Seaforth News, August 29, 1940.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Charged.” Zurich Herald, October 21, 1943.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Fined at Goderich.” The Wingham-Advance Times, August 22, 1940.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Refused Bail.” The Wingham Advance-Times, July 18, 1940.

“Looking Up Aliens Who Failed to Register.” The Exeter Times-Advocate, August 1, 1940.

“Police Arrest ‘Jehovah’s Witnesses.’” Seaforth News, June 27, 1940.

“Statement He Would Fight for Hitler Proves Costly.” The Wingham-Advance Times, October 5, 1939.

“To Register German Aliens.” The Seaforth News, October 12, 1939.

“Twenty-One Days.” The Lucknow Sentinel, October 28, 1943.

“Would Fight for Hitler-Arrested.” The Wingham Advance-Times, September 28, 1939.