by Sinead Cox | May 15, 2020 | Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

In this two-part series, Curator of Engagement & Dialogue Sinead Cox illuminates how the Second World War entered the walls of the Huron Historic Gaol. Click here for Part One: The ‘Defence of Canada’ in Huron County.

In the summer of 1940, when the Netherlands fell to Nazi Germany, a ripple effect extending to the Great Lakes would unexpectedly commit thirteen “alien seamen” to the Huron Jail.*

At the outset of the Second World War in 1939, the Oranje Line, also known in Dutch as Maatschappij Zeetransport N.V, was a relatively new Dutch-owned transport company that serviced Great Lakes routes. The Line had only commenced operations in 1937, and its fifth vessel in the Great Lakes, the 2,800 ton diesel freighter Prins Willem III was the first deep sea motor ship to come inland; she embarked on her maiden voyage in September, 1939.

On May 9th, 1940 the Prins Willem III departed neutral Antwerp, Belgium on a routine commercial journey under Captain W. P. C. Helsdingen. In the course of one day, the ship’s professional routine would be abruptly shattered. The Prins Willem III was off the coast of Flushing when a German bomb hit the water about 200 yards from the ship and caused a huge explosion and towering pillar of water. Germany had invaded the Netherlands. Planes were flying high and out of sight, but the crew could hear the whining sound of bombs as they fell nearby. Targeted by a machine gun onslaught from Nazi fighter planes, the ship escaped via the English channel. After narrowly surviving with their lives and the boat intact to reach England, the Dutch crew would soon learn that the formerly neutral Netherlands had capitulated and their home country was now occupied by Nazi Germany.

The ship continued on its planned journey to North American waters, docking at Montreal, Duluth, Milwaukee and finally Chicago on June 25th , successfully delivering a cargo of seeds and twine. At Chicago, the crew awaited orders regarding their next destination. Meanwhile, members of the Dutch government, including Queen Wilhelmina, had fled to London, England. The government in exile required all Dutch merchant vessels abroad to now sail under the British Merchant marines, and to report to an allied port to join the war effort: which could include transporting provisions or armaments. Canada being the closest allied country, the Netherlands Shipping Commission ordered the Prins Willem III to return to Montreal and “then embark for some unnamed foreign port,” according to the Chicago Daily Tribune. 17 out of the 19 crew members refused the orders.

The crew’s actions seemed to defy easy categorization as conscientious objection or mutiny. Captain Helsdingen assured the Chicago press that the men were neither striking, mutinous, nor even refusing to do their assigned jobs aboard the ship, but the crew would not leave the neutral waters of the United States (which would not enter the war until after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December, 1941). After their ordeal at the mercy of German bombs and guns, reluctance to return to a war zone aboard a ship that was not armed, and would not be provided an armed convoy, is hardly surprising. The Tribune quoted the crew as telling the captain, “If we cannot have weapons, we would rather spend our time in a United States jail than on the ocean.” They also feared for their families in a Nazi-occupied country and whether there could be reprisals against them—extending to arrests and transportation to concentration camps—for helping the allied cause by transporting munitions. According to the captain, the crew of the Prins Willem III feared Germany more than England.

The crew’s ‘sitdown strike’ left Commonwealth, Dutch and American authorities with no easy solutions. The standstill left most of the crew trapped on the ship, with only Captain Helsdingen legally permitted to go ashore. The crewmembers had no immigration documents to legally enter the United States, and because of the ongoing occupation of the Netherlands, the U.S. would not have been easily able to deport the sailors: thus Immigration authorities and the Coast Guard kept a close watch on the ship. The Captain could not take on an American crew to move the ship because of U.S. neutrality, and thus the Prins Willem III remained anchored unmoving at Navy Pier.

American newspaper reports emphasize that, rather than any assumed violent mutiny, the crewmembers were largely friendly and cheerful in their refusal to budge. During their months of isolation on board, the crew busied themselves cleaning, stripping and painting the masts, booms and deck, oiling “everything in sight, from door handles to winches,” and polishing every “spot of brass on the boat to glisten.” The Tribune declared when it finally left Navy Pier the Prins Willem III would probably be “the best painted, best oiled and best polished ship that ever left this port.” By September the crew’s plight had gained the sympathies of Dutch Chicagoans, who organized a committee to deliver care packages to the crew from pleasure boats.

The Dutch government-in-exile, the Oranje Line and Canadian authorities finally devised a solution in October: the Prins Willem III would take on a Canadian crew recruited from Montreal. Ten private police from the Pinkerton Detective Agency in the United States were hired to come aboard the ship with the fourteen Canadian crew-members to prevent resistance or sabotage, and the ship was escorted by the U.S. Coast Guard during its departure from Chicago. There was ultimately no violence from the crew confined below deck; according to Time Magazine, “internment in Canada looked better to the bored, sequestered Dutch than gazing at the Chicago skyline all day.” Their initial stop according to the American reports was to be an “unannounced Canadian destination,” later specified as an “Ontario Port.” That port was Goderich.

Ships in Goderich harbour, date unknown Photographer: Reuben R. Sallows (1855 – 1937)

On October 16th, 1940 the Prins Willem III—presumably painted, oiled and polished to perfection—arrived in the Goderich harbour. The secrecy surrounding the chosen port for the uncooperative crew’s disembarkment meant local customs workers were completely surprised by the ship’s unscheduled arrival, and began a tentative dialogue with Captain Helsdingen regarding next steps while further instructions from Ottawa were awaited. Again, the original crewmembers of the Prins Willem III were stuck in limbo on board, and again they made the most of it: according to the Clinton News-Record they came on deck “under the watchful eye of two [Pinkerton] detectives…getting great enjoyment out of perch fishing from the stern of the ship while they whistled modern American airs.” A local crowd of curious onlookers gathered at the harbour to gawk at the ship from a distance, and a host of exaggerated rumors quickly travelled throughout the community, including that the crew were held in irons and guarded by machine gun-wielding “G-men.”

Three days later, thirteen crew members quietly disembarked from the ship during the night, escorted by the RCMP in batches of no more than two men at a time.** Police vehicles delivered these men to the Huron Jail. The remaining crew changed their minds and agreed to sail with Captain Helsdingen and the Canadians. The Prins Willem III had vanished from the Goderich harbour by the next morning, and the Pinkerton Detectives caught a train back to Chicago.

Cell in the Huron Historic Gaol.

The crew’s confines on land might have been somewhat tighter and less comfortable than their previous situation on board the Prins Willem III. Detailed inmate records are not accessible from the 1940s, but regardless of how many prisoners were already ‘guests of the county’ at the time, the arrival of thirteen ‘alien seamen’ would have left the Huron Jail, which has only twelve cells, over-capacity and somewhat crowded. The crew, who may not have all spoken fluent English, would have received daily food rations worth 13 ¼ cents per inmate and would only be able to take fresh air from inside the jail’s walled courtyards.

The thirteen Dutchmen remained in jail for three weeks, until removed under RCMP guard on the afternoon of Saturday, November 9th; they left Goderich by rail. Their destination upon leaving Huron County was once again a mystery to the media and the public, but widely assumed to be a Canadian internment camp, where POWs, Jewish refugees from Europe, and civilian ‘enemy aliens’ of differing loyalties could be forced to cohabitate.

Captain Helsdingen and the Prins Willem III continued on to Montreal to enter into the service of the allies as originally ordered by the Dutch government-in-exile so many months earlier. The temporary Canadian replacements would eventually be relieved by a Dutch crew, and the boat outfitted with anti-aircraft guns and machine guns, but the Captain was to face continued refusals of work from his crew throughout the war. Confirming the original crew’s fears, an aerial torpedo struck the Prins Willem III off the coast of Algiers in March, 1943; the ship later capsized and sank, resulting in eleven deaths. None of the original crew from the Chicago sojourn were amongst the lives lost.

The international incident caused by the Prins Willem III in the Great Lakes may be largely forgotten today, but the plight of its crew demonstrates that the North American homefront was not always as peaceful or untouched by the conflict in Europe as we might imagine. Overnight, the capitulation of the Netherlands had left the crew of the Prins Willem III in a precarious situation after enduring a surely traumatizing ordeal during the Nazi invasion on May 10th, 1940. Facing uncertainty in the custody of North American authorities, versus what they might have deemed as an almost certain death re-entering a war zone without adequate protections, they took action (or rather inaction) that stymied multiple governments and brought the repercussions of the Second World War to an ‘Ontario Port’ as apparently nondescript as ours.

*A note on spelling: Jail & gaol are alternative spellings of the same word, pronounced identically. Both spellings were used throughout the history of the Huron Historic Gaol fairly interchangeably. Although as a historic site the Huron Historic Gaol uses the ‘G’ spelling more common to the nineteenth century, for this article I have chosen to employ the ‘J’ spelling that appeared more consistently in the 1940s.

** Newspaper reports record 16 crew members jailed, but the Jailer’s Report to Council for 1940 recorded 13 “alien seamen,” and this is also the number given by Martine van der Wielen-de Goede, who reviewed crewmembers’ testimonies later in London (see sources below).

Special thanks to Alana Toulin & Christina Williamson for research assistance that made this blog post possible!

Further Reading

Internment in Canada via the Canadian Encyclopedia: https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/internment

Internment resources from Library and Archives Canada: https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/politics-government/Pages/thematic-guides-internment-camps.aspx

Secondary Sources

Gillham, Skip, “The Oranje Line,” Telescope, Volume XXX, No. 5. (Sept-Oct 1981), pg 116-117.

Malcolm, Ian M, Shipping Losses of the Second World War, (Brinscombe Port Stroud: The History Press, 2013).

van der Wielen-de Goede, Martine, “Varen of brommen Vier maanden verzet tegen de vaarplicht op de Prins Willem III, zomer 1940,” Tijdschrift voor Zeegeschiedenis, No. 1 (Jan. 2008) Via https://docplayer.nl/173449011-Ten-geleide-tijdschrift-voor-zeegeschiedenis.html

Sources: Articles

“At Sea: Open Lanes.” Time Magazine, October 21, 1940, pg 29.

“Canada Jails 16 Dutch Seamen After Mutiny.” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 11, 1940.

“Dutch Crew Jailed.” The Wingham Advance-Times, October 17, 1940.

“Dutch Sailors Removed.” Huron Expositor, November 15, 1940.

“Dutch Sailors to Jail.” Clinton News-Record, October 24, 1940.

“Dutch Freighter Arrives in Goderich.” Clinton News-Record, October 17, 1940.

“Escapes Bombing; Reaches Chicago: Unloads Seeds, Twine.” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 27, 1940.

“Explains Dutch Sailors’ ‘strike’: They Fear Nazis.” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 28, 1940.

“Members of Crew Interned.” The Seaforth News, October 17, 1940.

“Sitdown Strike Strands Dutch Ship in Chicago.” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 26, 1940.

“Stranded Dutch Ship Sails with Canadian Crew: Idle Force Lets Sailors Aboard Quietly.” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 8, 1940.

“Strikers Mark Time.” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 27, 1940.

Wilson, Edward. “Aye, There’s Rub to Life Aboard Dutch Freighter: Crew Keeps Busy Polishing and Painting Ship.” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 7, 1940.

by Sinead Cox | May 18, 2017 | Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

May 18th is International Museum Day! Museums and historic sites across the world are opening their doors for free today. For those whom cannot visit the Huron Historic Gaol in person, Student Museum Assistant Jacob Smith delves into the building’s past to reveal how some of Huron’s youngest prisoners ended up behind bars.

During its operation [1841-1972], hundreds of children were arrested and sent to the Huron Jail. Their crimes ranged from arson and theft to drunkenness and vagrancy. The most common crime that children committed was theft. In total, thefts made up over half of all youth charges between 1841 and 1911. In total, children under the age of 18 made up 7% of the gaol population during that time.*

Occasionally, young people were sent to gaol for serious crimes. In 1870, William Mercer, age 17, was brought to the Huron Gaol and charged with murder. He was sentenced to die and was to be hanged on December 29, 1870. Thankfully for Mercer, his sentence was reduced to life in prison and was sent to a penitentiary. This is an example of an extreme crime for a young offender.

On many occasions, children were sent to gaol because they were petty thieves. Many young people who were committed for these types of crimes would only spend a few days in gaol. If the crime was more severe, children would be transferred from the gaol to a reformatory, usually for three to five years.

The youngest inmates that were charged with a crime were both seven years old. The first, Thomas McGinn, was charged in 1888 for larceny. He was discharged five days later and was sentenced to five years in a reformatory. The second, John Scott, was charged in 1900 for truancy; he was discharged the next day.

First floor cell block at the Huron Historic Gaol.

Unfortunately, some children were brought into gaol with their families because they were homeless or destitute. An example of this was in 1858, when Margaret Bird, age 8, Marion Bird, 6, and Jane Bird, 2, spent 25 days in gaol with a woman committed for ‘destitution’ (presumably their mother). Some children were also brought to the Huron Jail because their parents committed a crime and they had nowhere else to go while their parents were incarcerated. Samuel Worms, age 7, was sent to gaol with his parents because they were charged with fraud in 1865. He spent one day in the Gaol.

When reading through the Gaol’s registry, it is clear that times have certainly changed for young offenders. Most of the crimes committed by the young prisoners of the past would not receive as serious punishments today.

Here are some examples of their crimes in newspapers from around Huron County:

Richard Cain, 16, spent two days in jail.

The Huron Signal, 1896-09-17, pg 5.

Philip Butler, 15, spent eleven days in the Huron Jail.

The Exeter Advocate, 1901-08-29, pg 4.

Sources came from the Gaol’s 1841-1911 registry and Huron County’s digitized newspapers.

*Dates for which the gaol registry is available & transcribed. There were young people in the Huron jail throughout its history, into the twentieth century.

by Sinead Cox | Oct 20, 2016 | Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

“Is this place haunted?”: it’s one of the most common questions fielded by front desk staff at the Huron Historic Gaol. I’ve never set eyes on a ghost myself, but at least fifty-eight prisoners at the Huron Gaol died during their imprisonment. The jail’s four-cell-block design was intended for short stays—prisoners with multi-year sentences received transfers to larger institutions like Kingston Penitentiary—but for some Huron County inmates, theirs was indeed a death sentence in practice. Whether or not prisoners choose to revisit the grounds as ghosts, the recently launched online repository of Huron County newspapers has made it a little easier to research and shed light on their lives and deaths inside the Huron jail.

The Signal, 1911-6-15, pg 1

Infamously, three men—all under the age of thirty—hanged for murder at the Huron jail in Goderich: William Mahon in 1861, Nicholas Melady in 1869 (Canada’s final public hanging) and Edward Jardine in 1911. Although these are perhaps the best remembered demises at the jail, executions were rare and not representative of the fifty-eight known inmate deaths that took place here before 1913, the vast majority of which were the result of natural causes like old age and disease. The average age of deceased prisoners was sixty-three. The oldest inmate to die in the jail with a recorded age—often merely an estimate by the gaoler or gaol surgeon—was approximately ninety; the youngest fatality was a two-month old infant named Robert Vanhorn who had been committed with his young, unmarried mother in 1879.

The Signal, 1884-2-29, pg 2

Most of the inmates who died in the jail were in fact not criminals at all, but elderly persons committed as ‘vagrants’ because they were homeless, or too frail and sick to provide for themselves. Some were itinerants, but many were long-term Huron County residents without friends and family able to support them in their old age. Unmarried, widowed or childless labourers and domestics were especially vulnerable, as well as early settlers whose closest relatives still remained in the old country. When Seaforth servant Margaret Ainley died in the jail of typhoid fever in 1883, The Huron Signal reported that “her relatives live in England.” Eighty-one-year-old Matthew Shepherd, a native of Scotland and a veteran non-commissioned officer of Her Majesty’s 93rd Foot, had seen service in the West Indies as well as British North America; the veteran soldier was a resident of Ashfield Township for three decades when he died in jail, but “had no direct relatives in this country” according to a June, 1891 obituary in The Signal. Both Ainley and Shepherd’s committals had been for vagrancy.

Other prisoners suffered from mental illness, dementia or serious health problems that their families could not cope with. Seventeen-year-old Patrick Kelleher, for example, had exhibited symptoms of mental illness or developmental issues since his childhood. His parents were newly arrived Irish emigrants in the summer of 1883, when the strain of caring for him evidently became too difficult and he was committed to the Huron jail for insanity. Patrick died there of a seizure in January, 1884 while still awaiting transfer to the Provincial Asylum.

The Exeter Times, 1875-12-30, pg 1

Without a safety net of organized social services, responsibility for Ontario’s rural poor fell to local municipalities in the nineteenth century. Sometimes the needy received assistance in their own communities and homes, but the gaol was one of the earliest municipal buildings with a full-time staff, and provided a convenient location for local governments to clothe, feed and supervise these ‘wards of the county.’

Starting in the late 1870s, Joseph “Big Joe” Williamson faced repeated committals to the Huron jail for vagrancy-a common pattern for homeless prisoners who had nowhere to go when their sentences ended. A Huron Tract ‘pioneer,’ seventy-four-year-old Williamson was a former contractor and once-prominent figure in local politics—so gifted at storytelling that he was called ‘Huron’s bard’. He petitioned County Council’s gaol & courthouse committee to transfer him to a hospital in December, 1883. The committee subsequently recommended that he be removed to the Middlesex County Poor House, but instead “Big Joe” died of heart disease at the Huron Jail on January 14th, 1884. The Huron Signal’s obituary deemed Williamson’s fate a “misspent life…after a tendency to drink and a liking for conviviality brought him down to penury.”

The Huron Signal, 1884-3-21, pg 4

In the absence of a House of Refuge in Huron County, the jail became a de facto poorhouse, hospital, lying-in-hospital for unwed mothers and long-term care home. The jail staff*—consisting in the nineteenth-century of the gaoler, the matron (his wife or eldest daughter), the turnkey, gaol surgeon, and any servants or family members who lived on site—provided frontline care to the old and sick in addition to their duties of managing the gaol and guarding actual criminals. In 1884, when William Burgess, an inmate from Brussels with cancer in his leg, lay slowly dying in his jail cell, Jailor William Dickson and turnkey Robert Henderson took turns keeping a nightly vigil on the ward he occupied with another sick inmate. This cell-mate, Johnny Moosehead, had actually helped to nurse Burgess himself before he became too ill with erysipelas. Fellow inmates quite often helped the gaol staff provide the constant care needed for elderly or dying prisoners. In the case of George Whittaker, a seventy-year-old Brussels ‘lunatic’ who died in July 1881 of self-inflicted injuries, the gaoler also charged the man’s ward-mates to help provide vigilance against self-harm—unfortunately to little avail.

A formal coroner’s inquest with a jury of prisoners and citizens was mandatory for every inmate death. After the death of ninety-year-old ‘indigent’ Hugh Hall in April 1887, friends of his from the Clinton area sent a hearse to Goderich to claim the body for a proper funeral, but a holiday delayed the inquest and the hearse had to return to Clinton empty until the coroner and jury could be assembled. The ‘usual verdict’ of these inquests was ‘natural causes’; over a dozen inmates had their cause of death simply recorded as some variation of ‘old age’ or ‘senile decay’. Testimony at these inquests, however, afforded the gaol staff, including the gaoler, matron and gaol surgeon, an opportunity to decry the gaol’s tragic inadequacy as a home for the insane or terminally ill.

The Signal, 1891-10-16, pg 1

The plight of the jail’s long-term residents did not go completely unnoticed or forgotten by the rest of the county, as gaol staff, inquest juries, newspaper editors, and successive jail and courthouse committees demanded better care for Huron’s poor. Public reports of the Gaol and Court House Committee had recommended transferring both Matthew Shepherd and William Burgess to a poor house before their deaths. An 1884 editorial in the Huron Signal called for County Council to be ‘indicted for murder’ for neglecting to build a House of Refuge to shelter the poor in Huron County after decades of discussion. In October, 1891 the same newspaper ran an exposé on the lives of the old and sick inside the jail, describing the circumstances of each individual inmate, and lamenting the injustice that these individuals would soon perish in jail. For at least three of the prisoners profiled in that piece, this sad prophecy swiftly came to pass: octogenarian Mary Brady would die after being bedridden with a broken arm only a few months later, the blind and ill John McCann would pass away in less than a year, and John Morrow—committed 25 times for vagrancy before his death—died of heart failure exacerbated by choking in 1893.

The Signal article pronounced that the vagrants of the Huron County Jail were doomed to a ‘criminal’s funeral’-but what this entailed varied case by case. Although their fates may have been sadly predictable, the final resting place of the jail’s dead is sometimes unclear. Some, like Hugh Hall, had friends, neighbours, clubs or family members who claimed their loved ones’ bodies and paid funeral expenses; this appears to be the case for all three executed men. Despite reported rumours that victim Lizzie Anderson’s mother had asked for his body to inter beside her daughter’s, hanged murderer Edward Jardine, for example, received burial at Colborne Cemetery per his request. If no claimants came forward for a deceased ‘vagrant’, however, interment became more uncertain. The Exeter Times reported at least one prisoner, James Stinson of Hay Township, as being buried in a ‘Potter’s field’ in 1878-referring to an unmarked grave or ‘pauper’ section of a cemetery.

The Huron Signal, 1887-06-03, pg 4

By the 1880s regional Anatomy Inspectors were responsible for ensuring that unclaimed bodies were not buried at all, but instead sent to medical colleges for dissection and research. In 1895, Colborne Township’s Elizabeth Sheppard perished at the jail of ‘senile decay’; according to the Wingham Times, Goderich undertaker and county Anatomy Inspector William Brophey was preparing Sheppard’s body for conveyance “to Toronto for some use in the colleges,” when at the last moment a brother materialised to retrieve her for burial in Goderich.

The Exeter Advocate, 1894-06-07, pg 8

Instances of cadavers from the Huron County Jail successfully reaching Toronto medical students are unconfirmed***, but this would have followed the law. Huron County finally successfully constructed a House of Refuge in Tuckersmith Township in the 1890s, which has since evolved into the Huronview home for the aged. Today there is a monument to the residents buried there, but at the turn-of-the-century these interments at the House’s farm property were actually in conflict with legislation. By 1903, Keeper Daniel French had to be publicly reminded of the laws respecting the disposal of bodies at government institutions—all cadavers were supposed to be transferred to the regional Inspector of Anatomy within twenty-four hours if no ‘bona fide friends’ appeared to claim a corpse. French was liable for a $20 fine, but the current Huron County Warden advised him to continue burials. Local jailers, however, may have been more law-abiding.

Knowing that most deaths at the Huron Historic Gaol were due to long and lonely incarcerations caused by old age and infirmity, it’s hard to imagine many of these men and women returning to haunt the narrow corridors. They served virtual life sentences as an unfortunate consequence of poverty and isolation, and any added time in the afterlife seems undeserved. I don’t know if you can find the ghosts of the likes of Mary Brady or William Burgess stalking the courtyards after dark, but the reports of inmate interments we do have indicate that you can find the jail’s dead in cemeteries across Huron County, including those located in Hensall, Clinton, Seaforth, Brucefield, St. Columban, Goderich, Blyth, Dungannon, and Colborne. At the very least, the jail provides another place to remember and reflect upon the lives of the others, whose graves are unmarked and unknown.

*Living onsite meant that gaoler, matron and family members also sometimes breathed their last on site, including former matron Ann Robertson, Gaoler Edward Campaigne, and two young daughters of Jailer Joseph Griffin

***Since this post was published, further research using The Brussels Post newspapers has confirmed that at least two Huron inmates were sent to medical colleges for study: Mary Brady and William Shaw. Shaw’s son had requested that his father be buried in Howick Township, but couldn’t provide the funds himself.

Research for this blog post used historical newspapers made available via Huron County’s Newspaper Digitization project, as well as the gaol registry 1841-1911 and transcribed coroner’s reports available at the Huron County Archives Reading Room, Huron County Museum.

Start searching through online historical newspapers today to learn more secrets of Huron’s past!

by Sinead Cox | Aug 25, 2015 | Huron Historic Gaol, Special Events

The Huron Historic Gaol’s popular evening Tuesday and Thursday tours, Behind the Bars, are coming to an end for another year! Your last chance to meet historic prisoners and staff from the gaol’s past is Thursday, August 27th at 7-9pm. In celebration of another successful season, Colleen Maguire, one of Behind the Bars’ veteran volunteer performers, gives readers a behind-the-scenes glimpse of what it takes to get into character and travel back to the gaol’s past every Tuesday and Thursday evening in July and August.

It is Thursday again and in a few short hours I will walk back into the 1890s. That’s because I portray Mrs. Margaret Dickson in the Behind the Bars tours at the Huron County Gaol, Goderich.

These Behind the Bars Tours feature about 18 actors who portray real people who lived, worked and were inmates of the Gaol, now a National Historic Site.

Mrs. Dickson became the Gaol Matron aka Governess when her husband William became the Gaoler in 1876. Together the couple raised five of their own children while living and working in the gaol. This is my third year portraying this beloved matron. I have researched countless hours to learn everything I can about her and her husband. At any given moment I must be able to answer any question posed to me by the public and be able to accurately answer their queries as if I were Mrs. Dickson. Do come for a Behind the Bars Tour and hear the rest of the remarkable story.

With the research aside how does someone physically prepare for their role in Behind the Bars?

It’s an hour and 15 minutes before the big doors of the Gaol will open to admit the curious so they can relive the history and the people of the Gaol where the 21st century literally collides with the 19th century.

[Physical] preparation for my role began months ago when I began growing my hair. The gaol is hot and [after] two [previous] seasons sweltering while wearing a wig it was time to try something different with my [short] hair. By growing it long enough I am able to pin an artificial matching hairpiece bun on the back. Now with a bit of practice, I can take my hair from a modern style to one befitting an older matron in the late 1800s. Mrs. Dickson was 67 years old in the year I portray her.

Before and After: Volunteer Colleen Maguire transforms into Mrs. Margaret Dickson, gaol matron.

The process begins by trading my t-shirt for a 100% cotton camisole. I learned early on to remove any over-the-head garments before starting the hair. Based on a photograph of Mrs. Dickson from this time period I know that she had white hair, parted in the middle and pulled to the back. My own hair is white, but naturally wavy, so getting the right look requires using some hair wax, twenty-one bobby pins and a lot of hairspray.

While the hairspray dries, it’s on to the next phase. Black stockings, then long pantaloons with a drawstring in front that have to be tied with a double knot, as they have been known to come undone resulting in a potentially embarrassing wardrobe malfunction. I then step carefully into my crinoline rather than take it over my head. The most common mistake that women reenactors make is not having the proper underclothing so that their dress or skirt can hang properly and fully. By now my hair should be fairly lacquered into place, so it’s time to attach and pin the bun hairpiece on and remove some hair pins now that the hairspray has taken over. A quick glance at the clock tells me that I have approximately 15 minutes left.

It’s a hot July day, so I grab my spray bottle and mist my cotton camisole with cool water, just enough to be wet through but not wet enough that my next item of clothing– my high collared, long, full sleeved Victorian working blouse–will become wet. I carefully guide and slip the floor-length long cotton twill skirt over my head. The Victorians were so smart, the closure on the back of my shirt allows me to button it at three different waist sizes. A little shake and my shirts fall into place. Next I clip my pewter Chatalaine to my skirt waistband; on its four long chains hangs two small keys- one for my writing desk and the other for Dr Shannon, the Gaol surgeon’s medicine cabinet, a pencil, small scissors and a quarter-sized timepiece. Pinning an antique cameo pin on the front of my high collar, placing a wedding band on my finger, and putting on my pince-nez eyeglasses, the final glance in the mirror indicates the transformation is complete. With my driver’s licence tucked into the lining of my antique purse, I set off for the car. Here is where history collides, for getting into a compact car with long skirts and lots of clothing is a bit tricky. You don’t want to be driving down the street with an article of clothing sticking out of your car door.

The matron’s keys: part of Colleen Maguire’s Behind the Bars costume.

Once at the Gaol I climb the spiral staircase to the second floor Gaoler’s Apartment just as Mrs. Dickson would have done countless times. This is where the Gaoler and his wife and all their children lived. Well, that and a smallish cottage built in one of the courtyards of the Gaol in 1862. What about the Governor’s House [a two-storey home attached to the gaol] you ask? Well that wasn’t built until 1901, long after Mrs. Dickson had passed on in 1895.

Mrs. Dickson was prolific letter writer, whether it be asking for a raise or writing letters asking for a House of Refuge to be built in Huron County. She was a social worker long before it was a fashionable career for women. Consequently, I have chosen to use as my props a small writing desk, ink well, and nib pen. Each night I slip my black cotton sleeve protectors on and begin the task of writing grocery lists, and other letters. Sometimes I surprise the [other] actors by reading to them a letter from their family that I have crafted or handing Dr. Shannon [the gaol surgeon] a note about an newly admitted inmate. It’s all part of the improv that takes place throughout the evening.

It’s 7 PM and the big Gaol doors have opened and in have flooded the tourists anxious to experience what life is really like in a 19th-century Gaol.

“Please allow me to introduce myself. I am Mrs. William Dickson, the Gaol Governess.”

Need to know more about what goes on behind the scenes at Behind the Bars? Check out coordinator Madelaine Higgins’ earlier post about planning the event.

Do you want to volunteer at the Huron County Museum or Huron Historic Gaol? To learn more about the Friends of the Huron County Museum, email museum@huroncounty.ca

by Sinead Cox | Aug 24, 2015 | Huron Historic Gaol, Project progress

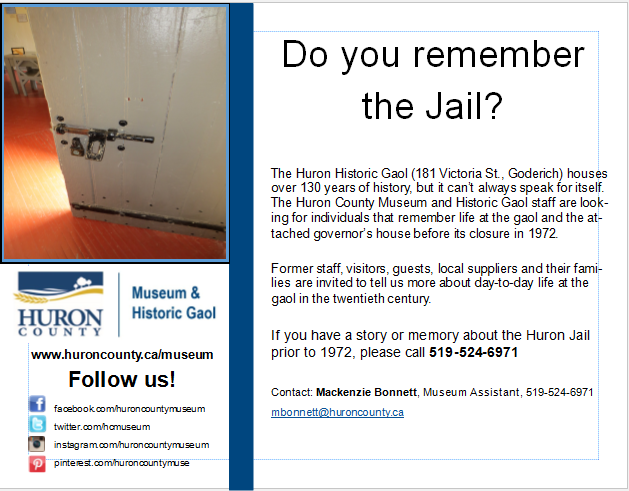

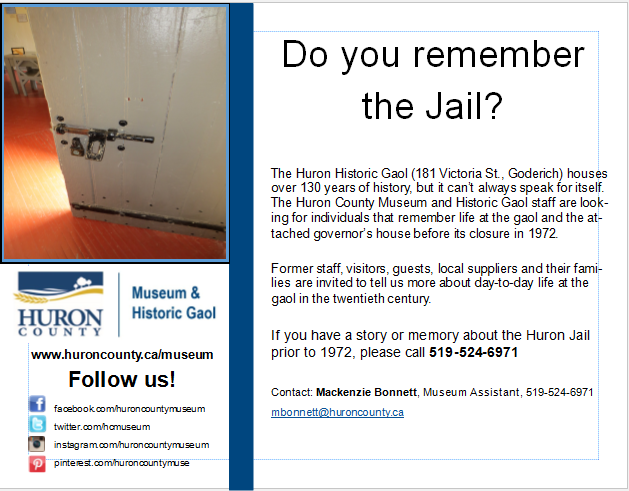

The Huron Historic Gaol was an operational jail from 1841 until 1972. Many Huron County residents still remember the building when it housed inmates, as well as the governor or superintendent (jailer) and his family in the adjoining house; museum staff wanted to hear their stories to gather a more complete picture of day-to-day life living or working in jail. This summer, student museum assistant Mackenzie Bonnett met interview-partners with memories of the building prior to its 1972 closure at the gaol; he shares his first experiences with oral history.

Following the recent death of a former notable gaol employee, the Huron Historic Gaol and the archives at the Huron County Museum received a series of inquires into their life and time spent at the Gaol. Through these inquiries staff realised there is relatively little we know about the personal experiences of those that spent time at the Gaol while it was still in operation. We decided that the best way to learn more about these stories would be to get them directly from the source; this started my summer Gaol oral history project.

Following the recent death of a former notable gaol employee, the Huron Historic Gaol and the archives at the Huron County Museum received a series of inquires into their life and time spent at the Gaol. Through these inquiries staff realised there is relatively little we know about the personal experiences of those that spent time at the Gaol while it was still in operation. We decided that the best way to learn more about these stories would be to get them directly from the source; this started my summer Gaol oral history project.

I sought out people with any connection to the Gaol whether they were inmates, guards, maintenance staff, volunteers or family of the governor (jailer). A press release was sent out in early June to various local newspapers asking anyone with these types of connections to contact the gaol. Before starting any interviews I had to prepare myself with questions to organize and keep focus during the interview. I also had to prepare for the logistics of an oral history project which requires consent and release forms which allow people to assign a future date for when the information from their interview can be used.

Over the summer I conducted three interviews that each had their own interesting stories that told a variety of things about the Gaol and its staff and inmates that were not known to our staff today. I heard stories from friends and family of past Gaol Governors that heard firsthand accounts of day to day operations of the Gaol including escape attempts and notable prisoners. I also heard from Gaol volunteers that gave important insight into how the Gaol and its inmates were viewed by the community it served. I hope that the stories I heard and transcribed can be use in the future to aid with research and the creation of further exhibits.