by Jacob Stevens | Sep 3, 2025

Join Curator of Engagement & Dialogue Sinead Cox for a presentation on the experiences of British migrant children placed in Huron County between the 1860s and the 1940s as farm labourers and domestic help.

This presentation is FREE or by donation. You can donate using the museum’s donation box in the lobby for cash and change, or via our Tip/Tap/Pay machine via card. Donations can also be made at the cash register at the front desk. Please note that seating in the theatre is limited and by a first come basis.

Please note that the stories shared may include discussion of child abuse and suicide.

This presentation and others are available as museum outreach.

ABOUT THE PRESENTER:

Sinead is an artefact with a Huron County provenance. As Curator of Engagement & Dialogue, she leads special events, educational programs and group tours. She also offers outreach programs throughout the county. Starting as a volunteer and summer student, Sinead has worked at the museum since 2011, and she’s served quite some time in gaol with our annual ‘Behind the Bars’ night tours, occasionally as a nineteenth-century vagrant. After completing her undergraduate degree at the University of Western Ontario and the University of Leeds in Yorkshire, England, Sinead received a Master’s degree in Public History from Carleton University. The Huron County Museum and Historic Gaol featured heavily in her Major Research Essay, which examined depictions of the poor in rural southwestern Ontario museums.

by Sinead Cox | May 7, 2020 | Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

In this two-part series, Curator of Engagement & Dialogue Sinead Cox illuminates how the Second World War impacted Huron County in unexpected ways at home, and even entered the walls of the Huron Historic Gaol. Click for Part Two, and the strange tale of how Dutch sailors became wartime prisoners in Huron’s jail.

During the Second World War, Canada revived the War Measures Act: a statute from the First World War that granted the federal government extended authority, including controlling and eliminating perceived homegrown threats. The Defence of Canada Regulations implemented on September 3, 1939 increased censorship; banned particular cultural, political and religious groups outright; gave extended detainment powers to the Ministry of Justice and limited free expression. In Huron County, far from any overseas battlefields, these changes to law and order would bring the Second World War closer to home.

Regulations required Italian and German-born Canadians naturalized as citizens after 1929 (expanded to 1922 the following year) to formally register as ‘enemy aliens’ and report once a month. In Huron County, jail Governor James B. Reynolds accepted the appointment of ‘Registrar of Enemy Aliens’ in the autumn of 1939, and the registration office was to operate from the jail in Goderich. There were also offices in Wingham, Seaforth and Exeter managed by the local chief constables of the police force.

Regulations required Italian and German-born Canadians naturalized as citizens after 1929 (expanded to 1922 the following year) to formally register as ‘enemy aliens’ and report once a month. In Huron County, jail Governor James B. Reynolds accepted the appointment of ‘Registrar of Enemy Aliens’ in the autumn of 1939, and the registration office was to operate from the jail in Goderich. There were also offices in Wingham, Seaforth and Exeter managed by the local chief constables of the police force.

In addition to its novel function as the alien registration office, the Huron Jail also housed any prisoners charged criminally under the temporary wartime laws. Inmate records from the time period of the Second World War cannot be accessed, but Reynolds’ annual reports submitted to Huron County Council indicate that one local prisoner was committed to jail under the ‘Defence of Canada Act’ in 1939, and there were an additional four such inmates in 1940. The most common charges landing inmates behind bars during those years were still typical for the county: thefts, traffic violations, vagrancy and violations of the Liquor Control Act (Huron County being a ‘dry’ county).

Frank Edward Eickemier, the lone individual jailed under the War Measures Act’s Defence of Canada regulations in 1939, was no ‘alien,’ but the Canadian-born son of a farm family in neighbouring Perth County. Nineteen-year-old Eickemier pled guilty to ‘seditious utterances’ spoken during the Seaforth Fall Fair, and received a fine of $200 and thirty days in jail (plus an additional six months if he defaulted on the fine). The same month the Defence of Canada regulations took effect, Eickemier had publicly proclaimed that Adolph Hitler’s Nazi Germany was undefeatable, and that if it were possible to travel to Europe he would join the German military. He fled the scene when constables arrived, but was soon pursued and arrested for “statements likely to cause disaffection to His Majesty [King George VI] or interfere with the success of His Majesty’s forces.” His crime was not necessarily his political views, but his disloyalty. The prosecuting Crown Attorney conceded, “A man in this country is entitled to his own opinion, but when a country is at war you can’t go around making statements like that.”

Bruce County law enforcement prosecuted a similar case in July of 1940 against Martin Duckhorn, a Mildmay-area farm worker employed in Howick Township, and alleged Nazi sympathizer. Duckhorn had been born in Germany, and as an ‘enemy alien’ his rights were essentially suspended under the War Measures Act, and he thus received an even harsher punishment than Eickemier: to be “detained in an Ontario internment camp for the duration of the war.”

Huron County Courthouse & Courthouse Square, Goderich c1941. A991.0051.005

In July of 1940, the Canadian wartime restrictions extended to making membership in the Jehovah’s Witnesses illegal. The inmates recorded as jailed under the ‘Defence of Canada Act’ in Huron that year were likely all observers of that faith, which holds a refusal to bear arms as one its tenets, as well as discouraging patriotic behaviours. That summer, two Jehovah’s Witnesses arrested at Bluevale and brought to jail at Goderich ultimately received fines of $10 or 13 days in jail for having church publications in their possession. Four others accused of visiting Goderich Township homes to discourage the occupants from taking “any side in the war” had their charges dismissed—due to a lack of witnesses. In 1943, the RCMP and provincial police collaborated to arrest another three Jehovah’s Witnesses in Goderich Township for refusing to submit to medical examinations or report their current addresses (therefore avoiding possible conscription); the courts sentenced the three charged to twenty-one days in the jail, afterwards to be escorted by police to “the nearest mobilization centre.”

By August of 1940, an item in the Exeter Times-Advocate claimed that RCMP officers were present in the area to ‘look up’ those individuals who had failed to comply with the law and promptly register as enemy aliens. A few weeks later, the first Huron County resident fined for his failure to register appeared in Police Court. The ‘enemy alien’ was Charles Keller, a 72-year-old Hay Township farmer who had lived in Canada for 58 years, emigrating from Germany as a teenager in 1882. According to his 1949 obituary in the Zurich Herald, Keller was the father of nine surviving children, a member of the local Lutheran church, and had retired to Dashwood around 1929. His punishment for neglecting to register was not jail time, but the fine of $10 and costs (about $172.00 today according to the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator).

Although incidences of prosecution under the ‘Defense of Canada Act’ in Huron County were few, the increased scrutiny and restrictions would have been felt in the wider community, especially for those minority groups and conscientious objectors directly impacted. Huron had a notable number of families with German origins, especially in areas like Hay Township where you can still see the tombstones of many early settlers written in German. The Judge who sentenced Frank Edward Eickemier for his public support of the Nazi regime in 1939 made a point of accusing him of casting a ‘slur’ on his ‘people’ and all German Canadians: the actions of the individual conflated with a much larger and diverse German community by a representative of the law. His case indicates that pro-fascist and pro-Nazi sentiment certainly did exist close to home, but a person’s place of birth or their religion was not the crucial evidence that could define who was or was not an ‘enemy.’

Next Week: Click for Part Two, and the strange tale of how stranded Dutch sailors ended up prisoners in the Huron County Jail during the Second World War.

*A note on spelling: Jail & gaol are alternative spellings of the same word, pronounced identically. Both spellings were used throughout the history of the Huron Historic Gaol fairly interchangeably. Although as a historic site the Huron Historic Gaol uses the ‘G’ spelling more common to the nineteenth century, for this article I have chosen to employ the ‘J’ spelling that appeared more consistently in the 1940s.

Further Reading

The War Measures Act via the Canadian Encyclopedia

Sources

Research for this blog post was conducted largely via Huron’s digitized historical newspapers.

“Faces Trial on Charge of Making Disloyal Remark.” Seaforth News, September 28, 1939.

“German Sympathizer Interned.” The Wingham-Advance Times, July 25, 1940.

“In Police Court.” Seaforth News, August 29, 1940.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Charged.” Zurich Herald, October 21, 1943.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Fined at Goderich.” The Wingham-Advance Times, August 22, 1940.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Refused Bail.” The Wingham Advance-Times, July 18, 1940.

“Looking Up Aliens Who Failed to Register.” The Exeter Times-Advocate, August 1, 1940.

“Police Arrest ‘Jehovah’s Witnesses.’” Seaforth News, June 27, 1940.

“Statement He Would Fight for Hitler Proves Costly.” The Wingham-Advance Times, October 5, 1939.

“To Register German Aliens.” The Seaforth News, October 12, 1939.

“Twenty-One Days.” The Lucknow Sentinel, October 28, 1943.

“Would Fight for Hitler-Arrested.” The Wingham Advance-Times, September 28, 1939.

by Sinead Cox | Apr 27, 2020 | Blog, Investigating Huron County History

Patti Lamb, museum registrar, outlines Huron County’s connection to the Disney legacy.

While most of us know the impact that Walt Disney has had on the entertainment world; whether that be through the amusement parks that bear his name or the children’s movies that we all love; few realize that his ancestral roots lie in Huron County. The connections in Huron County to Disney are rooted with his ancestors but modern day connections still exist.

Ancestral Connections

In 1834, Walt’s great grandfather Arundel Elias Disney, wife Maria Swan Disney and 2 year old Kepple Elias Disney; along with older brother Robert Disney and his wife, sold their properties in Ireland, departed from Liverpool, England and immigrated to America landing in New York on October 3, 1834. According to a written biography by Walt’s father there were 3 brothers that immigrated at the same time. The brothers went into business in New York while Elias (as he was most commonly called) made his way to Upper Canada settling in Goderich Township near Holmesville. By 1842, Elias had purchased Lots 38 and 39 on the Maitland Concession, a tract of land comprising of 149 acres. There, along the Maitland River, on Lot 38 he built one of the earliest saw and grist mills in the area. Brother Robert eventually purchased 93 acres on Lots 36 and 37 of the same concession. Elias and Maria had 16 children.

James and Ann (Swanson) Munro were among the first settlers in the Holmesville District and James was the first blacksmith in Holmesville (1834 – 1871). The base for this table is made from a birch stump that he selected from his 36 acre property (Lot 83, Maitland Concession) which he purchased August 15, 1832. The original 5 roots serve as legs. The top is of cherry lumber, sawn from some of the first logs to go through the saw mill owned by Elias Disney (great grandfather of Walt Disney). On the underside is carved the name “Emily” for one of James and Ann’s 12 children.

N7143.001b

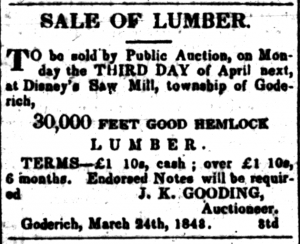

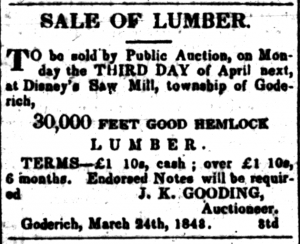

Advertisement for the sale of lumber from the Disney Saw Mill from the Huron Signal, March 24, 1848.

On March 18, 1858, Kepple Disney (Walt’s grandfather) married Mary Richardson, whose family were also early Goderich Township settlers near Holmesville. They purchased a farm on Lots 27 and 28 of Morris Township near Bluevale. Kepple and Mary had 11 children of which Elias Charles Disney (Walt’s father) was the oldest, born on February 6, 1859 in Bluevale and baptized in St. Paul’s Church in Clinton. All 11 children would eventually attend Bluevale Public School. Kepple did not really enjoy farming. He liked to travel and became intrigued in the drilling industry so in 1864, while keeping the homestead in Morris Township, he moved his family to Lambton County. He stayed in Lambton for 2 years before arriving in Goderich.

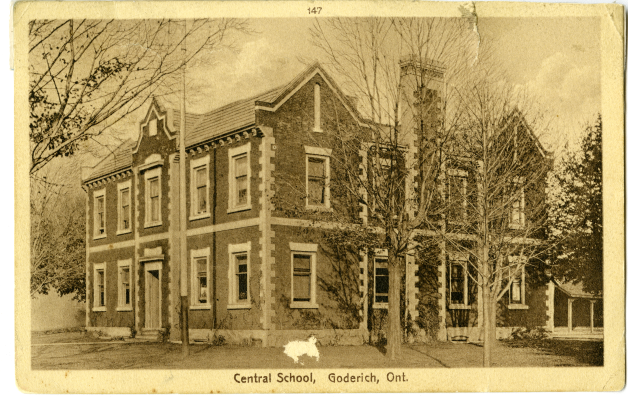

Here, Kepple was employed by Peter MacEwan and worked for him drilling for oil at a well in Saltford, just north of Goderich. Instead of oil, it was salt that was discovered, but that’s another story. In the July 1868 Voter’s List, the Disney’s appear as tenants of a house owned by James Whitely on Lot 275 in St. David’s Ward, Goderich. School records show that in 1868, 8 year old Elias and 6 year old Robert would attend Central Public School in Goderich (now part of the Huron County Museum). It appears the Disney’s left Goderich and moved back to the homestead in Morris Township sometime before 1869.

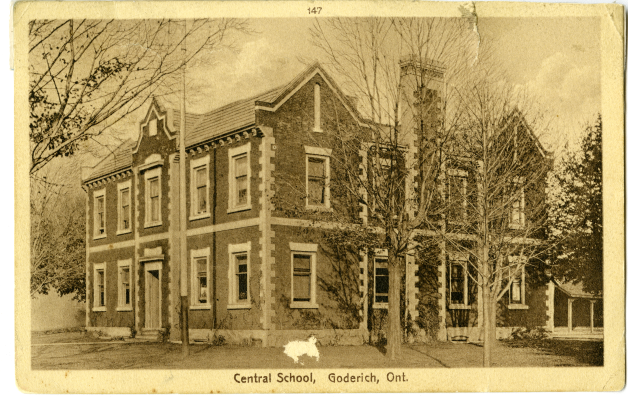

Postcard of Central School, N3103.

In 1878, Kepple left for California, where gold had been found, taking with him his oldest sons Elias and Robert. They stopped over in Ellis, Kansas and purchased 200 acres. Kepple sent for the rest of his family and his property in Morris Township was sold.

Ellis, Kansas is where Elias met neighbour Flora Call and on January 1, 1888 they were married. Kepple Disney’s family moved to Florida in 1884 and Elias, Flora and son later moved to Chicago. On December 5, 1901, Walter Elias (Walt) Disney was born, the 4th child of 5 for Elias and Flora Disney. After living in Chicago for 17 years, when Walt was 5 the family moved to Maceline, Missouri. They lived there for four years before moving onto Kansas City, Kansas.

At age 18, Walt started work as a commercial artist and from 1920 – 1922 was a cartoonist. He moved to Hollywood and opened a small studio (Walt Disney Studios) in 1923. He married Lillian Bounds on July 25, 1925 who was working for Walt Disney Studios at the time. The Disneys later had two daughters, Diane Marie and Sharon Mae. In 1928, Mickey Mouse, originally named Mortimer, was created.

In June 1947, Walt made a trip to Canada to visit his ancestral past. He stopped in at the Bluevale Post Office to enquire where the Disney homestead was located then drove to the farm that his father had spoken of so fondly. Walt drove on to Holmesville to visit the cemetery where his Disney great uncles and aunts, and his Richardson great grandparents are buried. Walt also visited Central School in Goderich and took some time to draw some cartoons for the students. He stayed the night in Goderich before travelling to Detroit and flying home.

Walt Disney died on December 15, 1966 at age 66 of lung cancer. His wife Lillian died September 16, 1997 at age 98.

Penhale Wagon

Huron County Disney connections also exist near the small village of Bayfield, Huron County. In 1974, as a hobby, Tom Penhale started building custom wagons. By 1983, it was a full time business. Tom’s business relationship with Disney started in December 1982 with the delivery of a set of hand crafted hames to the Walt Disney Ranch Fort Wilderness. In May 1983, he won the honour of building the show wagon that would compete in the 100th Anniversary of the Percheron Congress at the Calgary Stampede that coming June. He was chosen above many other craftsmen from all over North America.

Although a typical custom wagon would take about 3 months to complete, this one needed to be finished in 6 weeks. Official blueprints and a designer were flown in.

Working 16 hour days, with some local help, the wagon was completed on time. An artist came from the Disney World Studios in Florida to finish up. It was painted 4 different shades of blue, trimmed in 22 karat gold, and the lettering in silver spun with cotton.

Tom Penhale was given official recognition as the wagon builder when the Disney World Wagon was declared the World Champion Percheron Hitch during the 1983 Calgary Stampede.

Souvenir plate from the Goderich Township Sesquicentennial 1835 – 1985 featuring Tom Penhale’s Disney World wagon.

2018.0042.001

A Disney Parade

In July 1999, Goderich was the host for the first and only Canadian Hometown Disney Parade featuring Mickey Mouse, friends and characters. There were only 5 cities chosen in North America that year. Doug Fines, who was the President of the Goderich Chamber of Commerce at the time, submitted the winning essay to the contest to host the parade. The essay needed to convey true Mickey community spirit but of course having ancestral roots in Huron County helped as well. The organizers were expecting approximately 50,000 people to line the 2 ½ km route through Goderich. It is estimated that the final number was closer to 100,000.

While the connections between the famed Walt Disney and Huron County are few, their significance is no less meaningful. From ancestral roots to prize winning wagons and parades, it really is “a small world after all”.

by Sinead Cox | Jul 18, 2018 | Exhibits

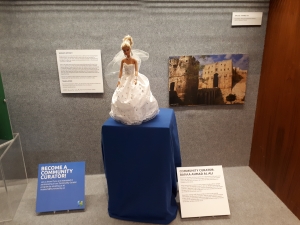

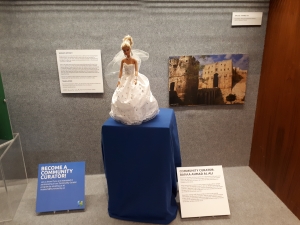

Sinead Cox, the museum’s Curator of Engagement & Dialogue, introduces the museum’s latest temporary exhibit, Community Curators: Newcomers (on display now).

From storage and display methods, to how and when we handle objects, museum staff endeavour to protect the artefacts entrusted to our care from the manifold dangers of shifting temperatures, chemical reactions, pests and damage–to preserve each and every artefact for future community access based on its unique needs. I encountered a new artefact-care dilemma recently however, when I had to think about the best way to preserve and protect an artefact’s existing smell while on display.

The 2018 participants for the museum’s recurring ‘Community Curators’ exhibit are both newcomers to Huron County. Instead of choosing an object from the museum’s collection like previous guest curators, they have very generously loaned an artefact of their own. Siham Mohammed of Wingham and Baraa Ahmed Al-Ali of Ashfield-Colborne-Wawanosh both fled with their families from war in Syria, and came to live in Huron County as sponsored refugees. I asked each volunteer curator to select an object or objects that related to their personal story or home country, and to translate the name of that object into English and their first language (Kurdish for Siham, Arabic for Baraa).

Because her family had few belongings when they came to Canada, twelve-year-old Baraa used her creativity to design and customize a doll’s dress to represent a typical Syrian wedding gown. Baraa’s handmade design evokes happy memories of family weddings in Syria and Lebanon when all of her brothers and sisters were still together.

Siham loaned two scarves that she has carried with her since she left Aleppo with her husband in 2011, first fleeing to Turkey for safety and eventually being matched with her new home community in Wingham. The scarves belonged to Siham’s mother, who she hasn’t seen since she left Syria. Although the scarves have lovely floral patterns, Siham doesn’t wear them in Canada as fashion accessories; she keeps them as keepsakes that remind her of her family still in Syria. The scarves remarkably still smell like her mother: strongly of jasmine perfume and more faintly of cigarette smoke.

Siham loaned two scarves that she has carried with her since she left Aleppo with her husband in 2011, first fleeing to Turkey for safety and eventually being matched with her new home community in Wingham. The scarves belonged to Siham’s mother, who she hasn’t seen since she left Syria. Although the scarves have lovely floral patterns, Siham doesn’t wear them in Canada as fashion accessories; she keeps them as keepsakes that remind her of her family still in Syria. The scarves remarkably still smell like her mother: strongly of jasmine perfume and more faintly of cigarette smoke.

The museum is very honoured to temporarily host such significant artefacts, and I knew it would be important to preserve the distinctive and familiar odour that adds so much personal value to the scarves. After consulting with our Museum Technician, Heidi Zoethout, we decided to encase each scarf individually in smaller plexi-glass boxes in the larger display case. Visitors will just have to imagine the strong flowery scent, and maybe think about what home smells like to them.

There are many objects donated to the museum’s permanent collection with similar stories: precious items carried from Ireland, England, Scotland, Germany, Holland or India brought with immigrants starting new lives in the presence of something that evokes the familiar sights, sounds, feelings, or scents of home. When the journey demanded that other possessions be sold or left behind, these were the items that remained. And that is really why, in my estimation anyway, it matters to pay attention to and try to preserve the texture, vibrancy, and integrity of these objects as much as we can—their value isn’t always something that you can put a price tag on, but it can encompass a sense of the past that you can see, touch, hear, taste or sometimes even smell.

To learn more about our curators’ stories, you can visit the Community Curators exhibit in the upper mezzanine of the Huron County Museum this summer. If you would like to be a community curator, contact us at museum@huroncounty.ca.

by Sinead Cox | May 9, 2016 | Exhibits, Investigating Huron County History

Not every new neighbor throughout Huron County’s history has been welcomed universally by the community; some have faced prejudice and discrimination. Education and Programming Assistant Sinead Cox, who led research for the current Stories of Immigration and Migration Exhibit, writes about the hostility and misconceptions faced by one of these migrant groups.

In 1895, an anonymous East Wawanosh farmer called for an end to the immigration of a despised immigrant group to Canada. Suspected of being untrustworthy and even violent, the farmer lamented to the Daily Mail & Empire that these migrants were “a curse to the country, as a rule.” The dangerous group he was referring to were young, poor, British children.

Article from the Daily Mail and Empire, July 23, 1895.

Between the 1860s and 1930s, U.K. charity homes sent thousands of urban boys and girls commonly known as ‘home children’ to Australia, South Africa and Canada as farm labourers or domestic servants. These young migrants feared as a threat to the moral character of Canadian society had little say in leaving the country of their birth, or their estrangement from any family they might have still had there. In 2010 the U.K. government officially apologized for the forced emigration of these children, which often involved what charity home founder Dr. Thomas Barnardo termed ‘philanthropic abduction’: sending poor children across the ocean without the knowledge of their still-living parents, siblings or guardians. Without knowing the children might be sent half a world away, caretakers had often placed them in the homes because of a sudden lack of funds to properly care for them, sometimes due to unemployment, insufficient wages, or the death or illness of a parent.

Between the 1860s and 1930s, U.K. charity homes sent thousands of urban boys and girls commonly known as ‘home children’ to Australia, South Africa and Canada as farm labourers or domestic servants. These young migrants feared as a threat to the moral character of Canadian society had little say in leaving the country of their birth, or their estrangement from any family they might have still had there. In 2010 the U.K. government officially apologized for the forced emigration of these children, which often involved what charity home founder Dr. Thomas Barnardo termed ‘philanthropic abduction’: sending poor children across the ocean without the knowledge of their still-living parents, siblings or guardians. Without knowing the children might be sent half a world away, caretakers had often placed them in the homes because of a sudden lack of funds to properly care for them, sometimes due to unemployment, insufficient wages, or the death or illness of a parent.

Child Migration was intended to ease urban poverty in the British Isles and agricultural labour shortages in the colonies.Once in Canada, the children were expected to work and attend school, and received infrequent inspection visits to monitor their welfare. Canadian employers tended to treat the young immigrants as hired hands, rather than adopted family members, and many changed homes frequently. Although rural Canada might have provided more employment opportunities than urban England, living among strangers often left the children vulnerable to abuse, neglect or overwork with tragic results. In 1923, Huron County farmer John Benson Cox was convicted of abusing Charles Bulpitt, the sixteen-year-old ‘home boy’ working for him, after Charles died by suicide in his care.

Excerpt from The Montreal Gazette, Feb. 8, 1924

At the time, some Canadians welcomed the cheap farm labour provided by the child migrants, while others feared that these lower class ‘waifs and strays’ must be ‘the offspring of criminals and tramps,’ and therefore inherently bad and dangerous to God-fearing citizens of the Dominion. In Canadian author L.M. Montgomery’s beloved classic, Anne of Green Gables, character Marilla Cuthbert famously dismissed the possibility of welcoming a child from the U.K. charity homes to Green Gables:

At first Matthew suggested getting a Barnardo boy. But I said ‘no’ flat to that. They may be all right—I’m not saying they’re not—but no London Street Arabs for me…I’ll feel easier in my mind and sleep sounder at nights if we get a born Canadian.

Public fears about these ‘street Arabs’ were no doubt influenced by the widespread popularity of the pseudoscientific practice of eugenics at the turn of the twentieth century. Eugenicists erroneously believed that some people were genetically superior to others, and these good traits would be diluted and society damaged by mixing with groups having supposedly inferior genes, including the mentally ill or developmentally challenged. Eugenicist policies were widely touted by many prominent Canadians, including philanthropists and legislators.

At an 1894 federal Select Standing Committee on Agriculture and Colonisation, East Huron Member of Parliament Dr. Peter Macdonald spoke against government subsidies for the immigration of ‘home children.’ His concerns were not based on the welfare and safety of the young immigrants, but on the potential ill effect their introduction would have on Canadian society, particularly because of their eventual intermarriage with existing Canadian settler families:

August 13, 1906 Globe and Mail article describing the arrival of 200 Barnardo Home boys, which included Bernard Brown.

Those children are dumped on Canadian soil, who, in my opinion, should not be allowed to come here at all. It is just the same as if garbage were thrown into your backyard and allowed to remain there. We find from the testimony of disinterested parties in this country, that a large number of these children have turned out bad, and are poisoning our population by intermarrying with them…I think myself this committee should unite in an expression of opinion that no such $2 a head should be paid by this government to bring such a refuse of the old country civilization, and pour it in here among our people. We take more means to purify our cattle than to purify our population?

Despite objectors like Macdonald, charity homes sent more than 100,000 British children to Canada, and today likely millions of Canadians are the descendants of these children who, despite the hardships of forced migration and separation from loved ones in childhood, often survived and persevered to earn a living and raise a family of their own. Although they had essentially been exiled by the British Empire, a huge proportion of ‘home boys’ also later volunteered to serve in the first and second world wars as young men.

Bernard Brown in his military uniform. He enlisted with the 161st Regiment of the Canadian Expeditionary Forces in January 1916. Photo courtesy of Brown Family.

One such child migrant, Bernard Brown (1896-1918), came to Huron County at ten years old. Bernard’s journey from a poor, struggling family in Northern Ireland that could not afford to feed all of their children, to an English charity home, to a Tuckersmith Township farm, and finally to the battlefields of France, was featured in the Huron County Museum’s Stories of Immigration and Migration, a temporary exhibit that tracks the narratives of seven families who came to our county between 1840 and 2007.

Similarly to many refugee families today, child migrants like Bernard Brown did not choose Huron County as their ultimate destination, but were matched there. When Bernard was placed with a couple in Tuckersmith, he was separated from his younger brother Edward whom Barnardo’s sent to Ripley, Bruce County. In hindsight, cases of mistreatment and neglect indicate that these young people an ocean away from loved ones, unable to return home and at the mercy of strangers, ultimately had much more to fear from Canadians than Canadians had to fear from them. The eventual success and resilience of those who survived childhood and the millions among us who can today claim a ‘home child’ as an ancestor are a testament to the fact that although the U.K and Canadian governments may have tragically failed them, the ‘home children’ contributed immeasurably to our communities rather than ‘poisoned’ them.

To find out more about the experience of one home child in Huron County, see Bernard’s story when you visit Stories of Immigration and Migration, on display in the Temporary Gallery at the Huron County Museum until October 15th, 2016. Are you descended from a home child? Share your family’s story with us tagged #homeinhuron or add it to the visitor-submitted stories in the exhibit.

Between the 1860s and 1930s, U.K. charity homes sent thousands of urban boys and girls commonly known as ‘home children’ to Australia, South Africa and Canada as farm labourers or domestic servants. These young migrants feared as a threat to the moral character of Canadian society had little say in leaving the country of their birth, or their estrangement from any family they might have still had there. In 2010 the U.K. government officially apologized for the forced emigration of these children, which often involved what charity home founder Dr. Thomas Barnardo termed ‘philanthropic abduction’: sending poor children across the ocean without the knowledge of their still-living parents, siblings or guardians. Without knowing the children might be sent half a world away, caretakers had often placed them in the homes because of a sudden lack of funds to properly care for them, sometimes due to unemployment, insufficient wages, or the death or illness of a parent.

Between the 1860s and 1930s, U.K. charity homes sent thousands of urban boys and girls commonly known as ‘home children’ to Australia, South Africa and Canada as farm labourers or domestic servants. These young migrants feared as a threat to the moral character of Canadian society had little say in leaving the country of their birth, or their estrangement from any family they might have still had there. In 2010 the U.K. government officially apologized for the forced emigration of these children, which often involved what charity home founder Dr. Thomas Barnardo termed ‘philanthropic abduction’: sending poor children across the ocean without the knowledge of their still-living parents, siblings or guardians. Without knowing the children might be sent half a world away, caretakers had often placed them in the homes because of a sudden lack of funds to properly care for them, sometimes due to unemployment, insufficient wages, or the death or illness of a parent.