Researching Canada’s ‘Last Public Hanging’

The following blog posts were originally published by Carling Marshall-Luymes on her personal blog while she was an intern for the Huron County Museum & Huron Historic Gaol in 2007. You can see the exhibit on the history of capital punishment on permanent display in Cell Block 1 when you visit the Huron Historic Gaol today.

The Executioner

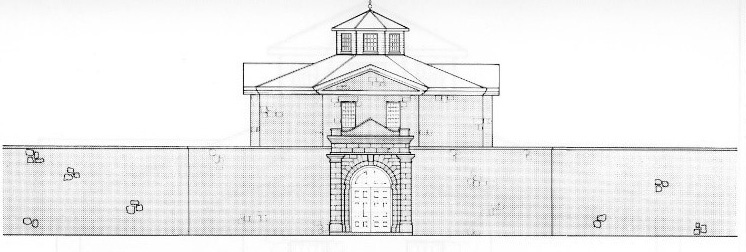

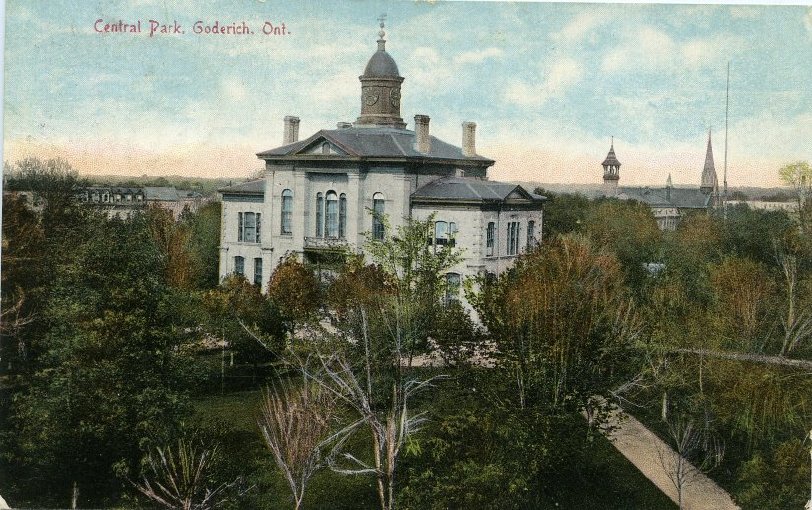

I’ve begun my internship at the Huron County Museum and Historic Gaol and I’m currently researching public hangings in (Upper and Lower) Canada for an upcoming exhibit. Three men were hanged at the Gaol in Goderich (1861, 1861 and 1911), all for murder; the first two were public hangings. I’ve set out to answer, among other things, why people were hanged, why such large crowds of spectators came out to watch hangings and why public hangings. These began as easy questions, to which I expected to find straight forward answers, but their answers are proving less simple than I had anticipated and I intend to shift the nature of my blog by writing about my research.

I work where Steven Truscott was incarcerated at age 14 during his 1959 trial for the rape and murder of schoolmate, 12 year old Lynne Harper, and became the youngest Canadian sentenced to death before his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. Thinking about Steven Truscott everyday and seeing the emotional response visitors have to his case, my assumption was that capital punishment (both public and behind prison walls) was abolished on the basis of humanity towards the convicted; but my research as opened my eyes to a lot of arguments for the abolishment of capital punishment.

John Radclive, Canada’s first professional hangman was appointed in 1892 after carrying out several successful hangings for various Ontario sheriffs. Most career hangmen were destroyed by their profession and Radclive was no exception. During his career Radclive began a ritual of finishing a full bottle of brandy after each execution; he drank excessively both before and after hangings. In a Star interview in Dec. 1906, Radclive spoke of himself: “I am a sick man, too sick to talk,” he said. “I have been sick a long time, very sick.” He died in February 1911, at 55, of cirrhosis of the liver at home in Toronto.

There seems to be some similarity between Radclive and the hangman hired by the Huron District gaol governor {William] Robertson [in 1861] – alcoholism. In a telegram discussing the hangman’s journey from Toronto to Goderich, Robertson is warned that the hangman is an unreliable drunkard, and a turn-key is thus being sent with him.

In an interview with psychologist Rachel MacNair, Radclive described his internal torment:

“Now at night when I lie down,” he said, “I start up with a roar as victim after victim comes up before me. I can see them on the trap, waiting a second before they meet their Maker. They haunt me and taunt me until I am nearly crazy with an unearthly fear.”

Public attitudes towards the hangman must have furthered his torment. In 1900 the Star wrote of Radclive: “If he were a man of delicate sensibilities he would not be the hangman. He is a necessity in our system, but he should be treated as if he is the hole in the floor of the gallows.” At the same time, a 1910 Globe editorial wrote on the role of the hangman: “It is an unpleasant subject, but it is a public question, and it is a public function for which all are reposnsible.” At a time when the population supported capital punishment I find it ironic that the they were so repulsed by the man carrying out their will. Countless people have to be involved in an execution by the state, directly or indirectly and in addition to the hangman, and I’ve realized the significance of acknowledging the psychological stress on these men and women as part of the case against capital punishment.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – — – – – — – – – – – – – — – – – – – – – – – – – –

The agony of the executioner; How a Parkdale man became our first official hangman and was destroyed by it. By Patrick Cain; [ONT Edition]

PATRICK CAIN Patrick Cain. Toronto Star. Toronto, Ont.: May 20, 2007. pg. D.4

Capital Punishment in Canada. Department of Justice http://www.justice.gc.ca/en/news/fs/2003/doc_30896.html

Canada's Last Public Hanging?

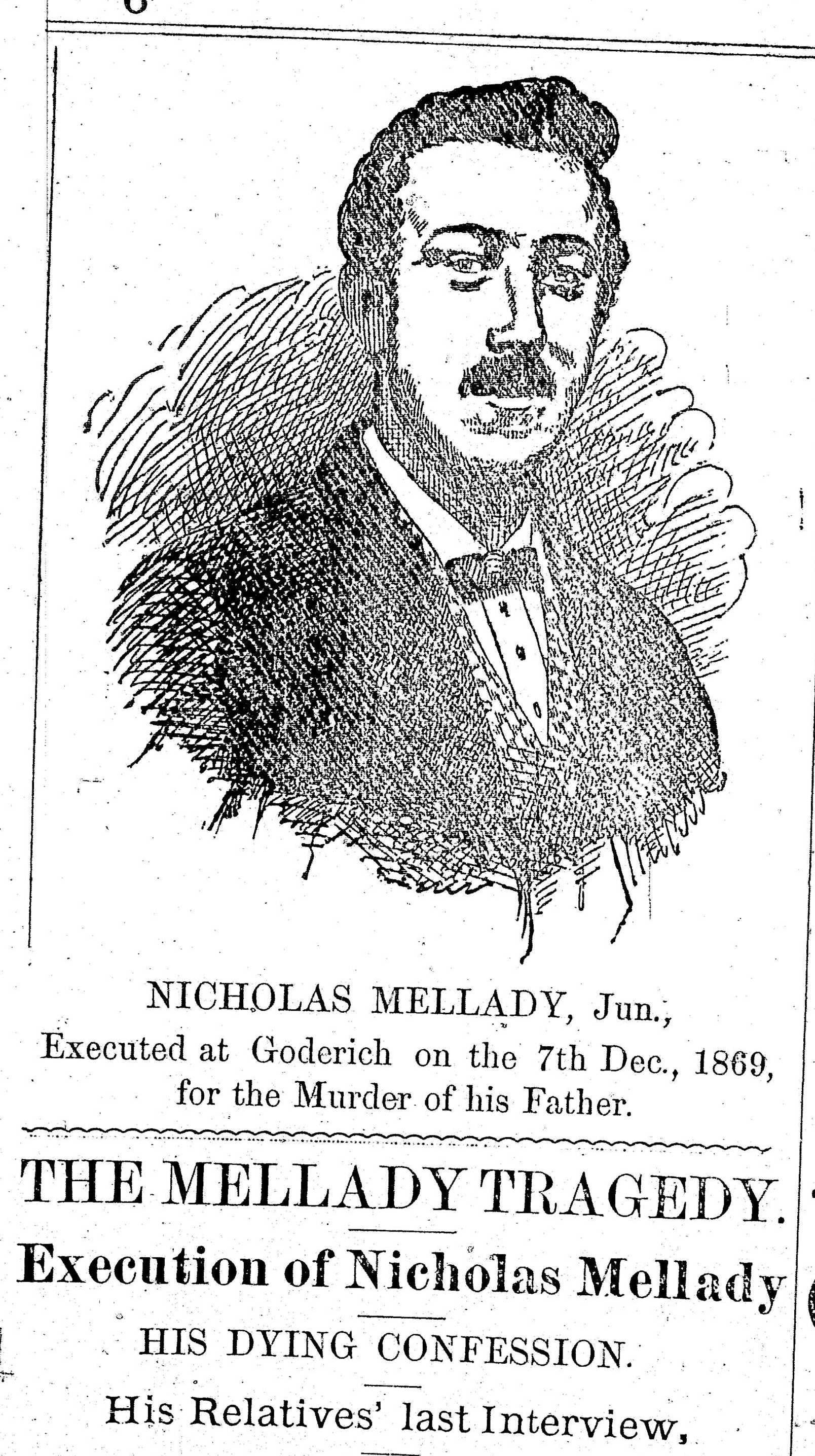

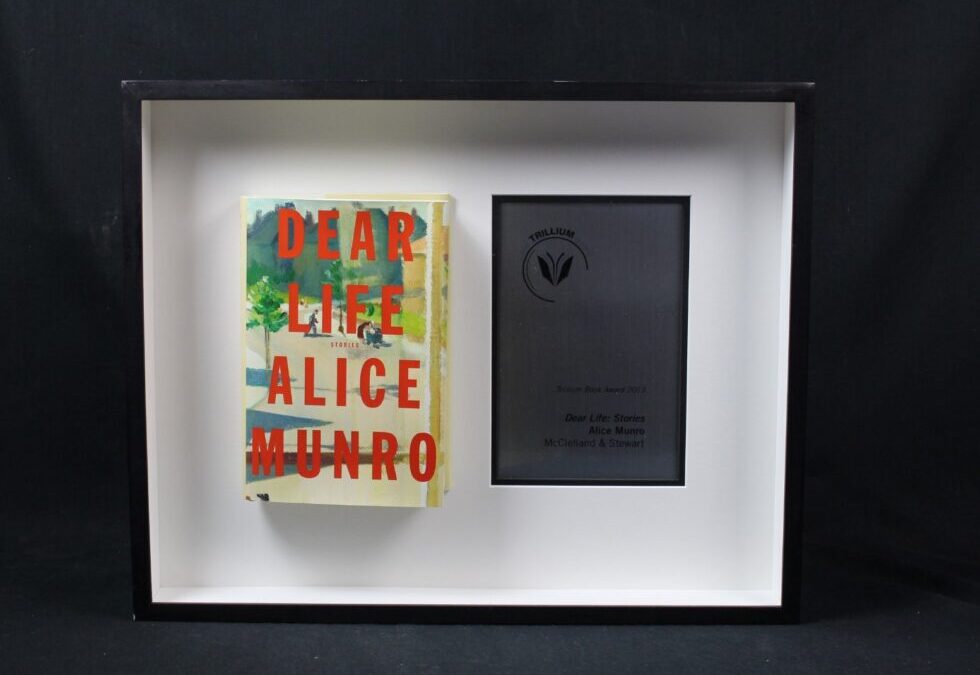

The hanging of Patrick Whelan at the Carleton County Jail on February 11 1869 for the assassination of MP and Father of Confederation D’Arcy McGee [left] is mistakenly claimed to be the last public hanging in Canada. Ten months later, on December 7, 1869, Nicholas Melady was hanged in Goderich at the Huron District Gaol for the murder of his father and step-mother. A recently published book detailing the crime and hanging, by Melady’s descendant John Melady, is titled Double Trap: Canada’s Last Public Hanging.

However – in 1869, Canada only included the provinces of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Hangings continued in public in areas that had not yet entered Confederation, such as the prairie provinces and BC.

While hangings were performed behind prison walls, the public was often still able to watch.

- The Sheriff could and often did invite interested spectators and newspaper reporters.

- Spectators were known to climb any nearby structure that would allow them to see into the yard. At the Montreal execution of Timothy Candy in 1910, dozens of people viewed the hanging from the roofs of adjoining houses. In this photo of the 1904 execution of Stanislau Lacroix in Hull, you can see the crowds on the nearby rooftops and telephone poles.

- Crowds of excited spectators were hard to stop. In March 1899, 2,000 uninvited guests stormed a Montreal gaol to witness a hanging, joining the 200 witnesses already inside the prison yard.

- The law was not always followed.

- The hanging scaffold was sometimes built taller than the prison walls to allow for public viewing.

An elderly museum patron noted several years earlier that he recalls watching gallows being built in public in Hamilton while riding the streetcar. Was this a case where the gallows were built higher than the prison walls to allow curious spectators a view? or was the law simply ignored? I’m not sure I can claim for certain that the hanging of Melady in Dec. 1869 was the last public hanging even in the provinces within Confederation at the time.

Legislating the End to Public Hanging...A Clarification

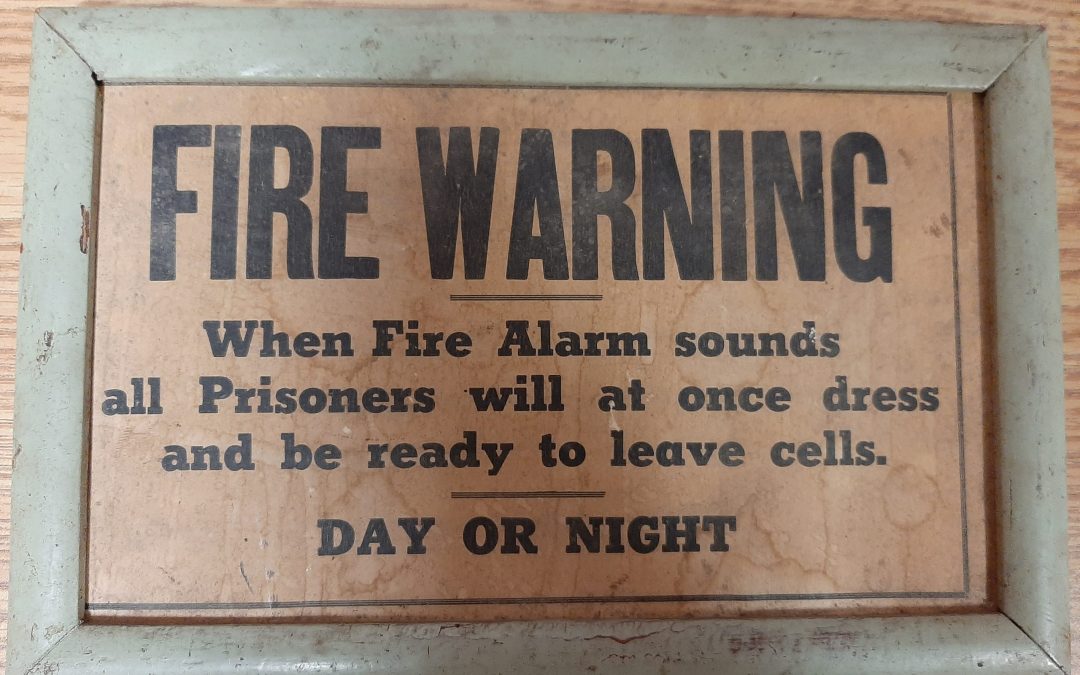

- Executions were to be carried out within the walls oft he prison in which the offender was confined at the time of execution

- Executions should take place at 8 am

- Hanging should continue to be the mode of execution

- A black flag was to be raised after an execution and remain up for one hour

- The prison bell (or the bell of a neighbouring church) was to ring for 15 minutes before and 15 minutes after an execution

After receiving a copy of “Act 32-33 Victoria c. 29” from the Library of Parliament it’s clear that Section 109 of the Act, which went into effect 1 January 1870, is actually the legislation ending public hanging, declaring:

“Judgment of death to be executed on any prisoner after the coming into force of this Act, shall be carried into effect within the walls of the prison in which the offender is confined at the time of execution.”

Why did Canada abolish public hanging?

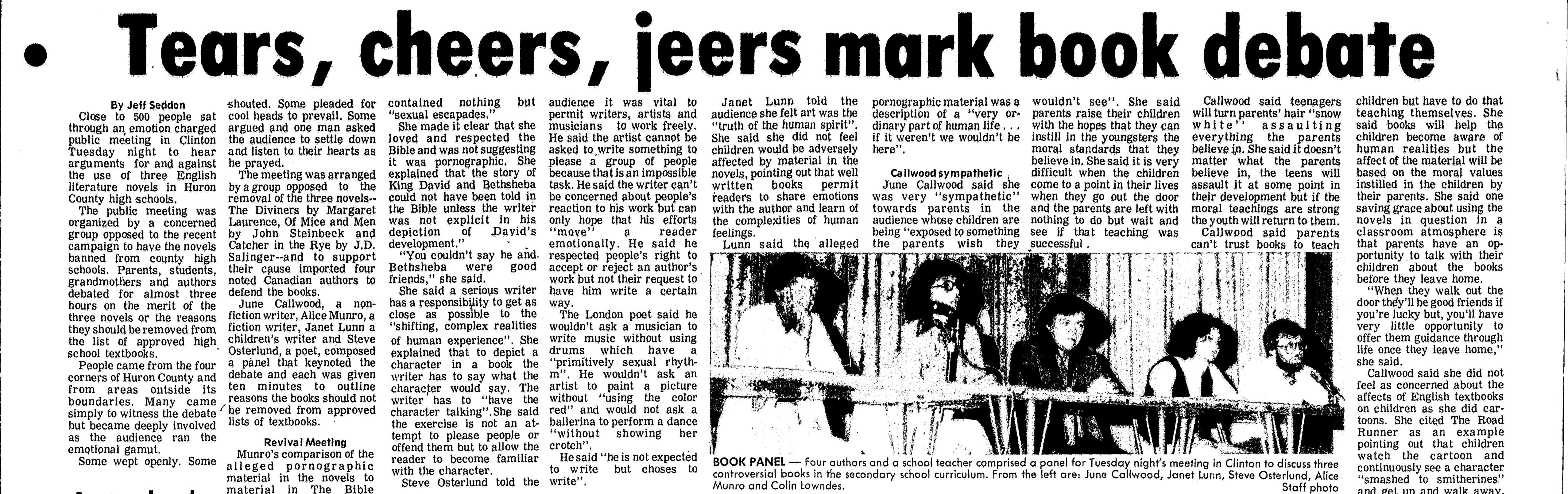

The end of public hangings in Canada under Act 32-33 Victoria chapter 29 brought relief to the general public but I was surprised to find that this was not because they disagreed with the death penalty (though some did), but largely because of the crowds that came to watch the executions.

People argued that public hangings should end for many reasons, and the ‘hanging crowd’ was a significant reason. People complained about rowdy crowds that showed up to watch hangings. When public hangings ended in England, the Times of London reported:

We shall not in the future have to read how, the night before the execution, thousands of the worst characters in England, abandoned women and brutal men, met beneath the gallows to pass the night in drinking in buffoonery, in ruffianly swagger and obscene jest.

Many polite Victorians felt that ending public hangings would advance civilization and they themselves felt uncomfortable watching hangings; at the same time they found the rowdy crowds’ fascination with death, obscene language and gestures, and disrespect for authority embarrassing.

Many also felt that death wasn’t solemn enough: the carnival-like atmosphere among the crowds that watched the executions prevented people from being deterred to commit crimes. It was also argued that by watching hangings, people were familiar with death and would no longer value human life or feel compassion towards others.

What I was most surprised to find that was by ending public hangings, the perpetuation of the death penalty was actually ensured. If people did not have to deal with the crowd, they would no longer have a reason to protest hangings. By making the hangings private, the death penalty could continue.

Capital punishment: Huron County opinion in 1869

Jesse Imeson was formally charged yesterday at the Goderich courthouse, about a two blocks away from where I was working at the Historic Gaol. By my lunch break, which I took at a shady picnic table on the courthouse grounds, the media circus had died down. Later, listening to the news, I was surprised to hear not that a crowd had gathered that morning by the courthouse, but that they had shouted at him and called out to reinstate the death penalty.

While researching the exhibit on public hanging, I was curious about what Huron County residents felt about the death penalty then, and I was surprised by a 11 Dec 1869 editorial in the Seaforth Expositor we had in our archives. The editor argued that public execution wasn’t an effective deterrent against crime, and crude and rowdy crowds had become hardened by watching public executions.

On the Melady hanging, he wrote:

We hope in the name of God – in the name of humanity – that capital punishment may soon be abolished in this ‘our Canada,’ and placed where it ought to be, with the grim relics of barbarous times.

I was hoping for a variety of letters to the editor in response, but as they were uncommon in this paper at the time, there was only one that seems to favour the death penalty:

The man that violates the law is a criminal, and is a scoundrel of whom we should get rid of in the most available way.

Semi-public? - The Hoag Hanging, Walkerton - 1868

The Sheriff then examined the fatal apparatus; the masked executioner did his work; and the body dropped within the gaol wall, depriving the gaping and motley crowd, some of them women with children in their arms, of the awful spectacle of the body quivering on the rope for a few minutes, perhaps five or six. A number of people were inside the wall and saw the whole [The Globe, 16 December 1868].

At this point I was concerned that perhaps the Melady hanging at our Huron County gaol may have also only been ‘semi-public’ and maybe not the last officially public hanging. I was found The Globe article on the Melady hanging [though blurry to read], which states that Melady was taken from ” the northern exit of the prison, ascended a temporary staircase, and took his position on the scaffold, which was on a level with the prison wall” and suggests that the hanging was entirely public.

However, there is always the possibility that though Melady ascended the stairs to the gallows publicly, because the scaffold was level with the prison wall, the trap could have been on the opposite side of the wall, and he could have dropped out of public view. It seems unlikely however that, as I mentioned in a previous post, both the Seaforth Expositor and The Globe would have made reference to it as the last public hanging if it was only ‘semi-public’ like the Hoag hanging.