by Sinead Cox | Apr 27, 2020 | Blog, Investigating Huron County History

Patti Lamb, museum registrar, outlines Huron County’s connection to the Disney legacy.

While most of us know the impact that Walt Disney has had on the entertainment world; whether that be through the amusement parks that bear his name or the children’s movies that we all love; few realize that his ancestral roots lie in Huron County. The connections in Huron County to Disney are rooted with his ancestors but modern day connections still exist.

Ancestral Connections

In 1834, Walt’s great grandfather Arundel Elias Disney, wife Maria Swan Disney and 2 year old Kepple Elias Disney; along with older brother Robert Disney and his wife, sold their properties in Ireland, departed from Liverpool, England and immigrated to America landing in New York on October 3, 1834. According to a written biography by Walt’s father there were 3 brothers that immigrated at the same time. The brothers went into business in New York while Elias (as he was most commonly called) made his way to Upper Canada settling in Goderich Township near Holmesville. By 1842, Elias had purchased Lots 38 and 39 on the Maitland Concession, a tract of land comprising of 149 acres. There, along the Maitland River, on Lot 38 he built one of the earliest saw and grist mills in the area. Brother Robert eventually purchased 93 acres on Lots 36 and 37 of the same concession. Elias and Maria had 16 children.

James and Ann (Swanson) Munro were among the first settlers in the Holmesville District and James was the first blacksmith in Holmesville (1834 – 1871). The base for this table is made from a birch stump that he selected from his 36 acre property (Lot 83, Maitland Concession) which he purchased August 15, 1832. The original 5 roots serve as legs. The top is of cherry lumber, sawn from some of the first logs to go through the saw mill owned by Elias Disney (great grandfather of Walt Disney). On the underside is carved the name “Emily” for one of James and Ann’s 12 children.

N7143.001b

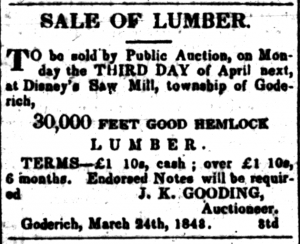

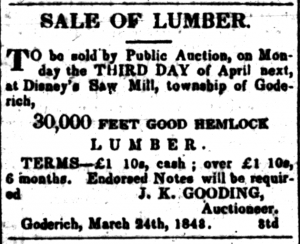

Advertisement for the sale of lumber from the Disney Saw Mill from the Huron Signal, March 24, 1848.

On March 18, 1858, Kepple Disney (Walt’s grandfather) married Mary Richardson, whose family were also early Goderich Township settlers near Holmesville. They purchased a farm on Lots 27 and 28 of Morris Township near Bluevale. Kepple and Mary had 11 children of which Elias Charles Disney (Walt’s father) was the oldest, born on February 6, 1859 in Bluevale and baptized in St. Paul’s Church in Clinton. All 11 children would eventually attend Bluevale Public School. Kepple did not really enjoy farming. He liked to travel and became intrigued in the drilling industry so in 1864, while keeping the homestead in Morris Township, he moved his family to Lambton County. He stayed in Lambton for 2 years before arriving in Goderich.

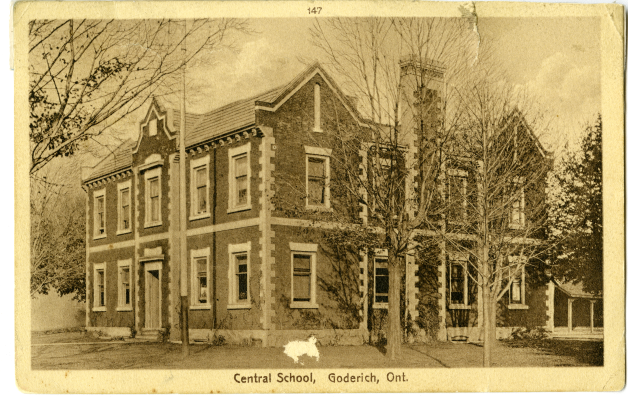

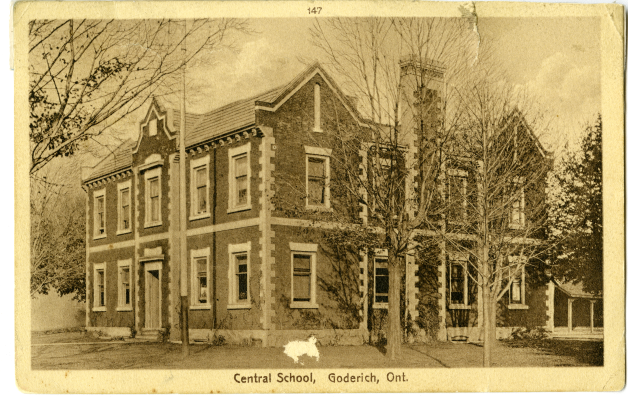

Here, Kepple was employed by Peter MacEwan and worked for him drilling for oil at a well in Saltford, just north of Goderich. Instead of oil, it was salt that was discovered, but that’s another story. In the July 1868 Voter’s List, the Disney’s appear as tenants of a house owned by James Whitely on Lot 275 in St. David’s Ward, Goderich. School records show that in 1868, 8 year old Elias and 6 year old Robert would attend Central Public School in Goderich (now part of the Huron County Museum). It appears the Disney’s left Goderich and moved back to the homestead in Morris Township sometime before 1869.

Postcard of Central School, N3103.

In 1878, Kepple left for California, where gold had been found, taking with him his oldest sons Elias and Robert. They stopped over in Ellis, Kansas and purchased 200 acres. Kepple sent for the rest of his family and his property in Morris Township was sold.

Ellis, Kansas is where Elias met neighbour Flora Call and on January 1, 1888 they were married. Kepple Disney’s family moved to Florida in 1884 and Elias, Flora and son later moved to Chicago. On December 5, 1901, Walter Elias (Walt) Disney was born, the 4th child of 5 for Elias and Flora Disney. After living in Chicago for 17 years, when Walt was 5 the family moved to Maceline, Missouri. They lived there for four years before moving onto Kansas City, Kansas.

At age 18, Walt started work as a commercial artist and from 1920 – 1922 was a cartoonist. He moved to Hollywood and opened a small studio (Walt Disney Studios) in 1923. He married Lillian Bounds on July 25, 1925 who was working for Walt Disney Studios at the time. The Disneys later had two daughters, Diane Marie and Sharon Mae. In 1928, Mickey Mouse, originally named Mortimer, was created.

In June 1947, Walt made a trip to Canada to visit his ancestral past. He stopped in at the Bluevale Post Office to enquire where the Disney homestead was located then drove to the farm that his father had spoken of so fondly. Walt drove on to Holmesville to visit the cemetery where his Disney great uncles and aunts, and his Richardson great grandparents are buried. Walt also visited Central School in Goderich and took some time to draw some cartoons for the students. He stayed the night in Goderich before travelling to Detroit and flying home.

Walt Disney died on December 15, 1966 at age 66 of lung cancer. His wife Lillian died September 16, 1997 at age 98.

Penhale Wagon

Huron County Disney connections also exist near the small village of Bayfield, Huron County. In 1974, as a hobby, Tom Penhale started building custom wagons. By 1983, it was a full time business. Tom’s business relationship with Disney started in December 1982 with the delivery of a set of hand crafted hames to the Walt Disney Ranch Fort Wilderness. In May 1983, he won the honour of building the show wagon that would compete in the 100th Anniversary of the Percheron Congress at the Calgary Stampede that coming June. He was chosen above many other craftsmen from all over North America.

Although a typical custom wagon would take about 3 months to complete, this one needed to be finished in 6 weeks. Official blueprints and a designer were flown in.

Working 16 hour days, with some local help, the wagon was completed on time. An artist came from the Disney World Studios in Florida to finish up. It was painted 4 different shades of blue, trimmed in 22 karat gold, and the lettering in silver spun with cotton.

Tom Penhale was given official recognition as the wagon builder when the Disney World Wagon was declared the World Champion Percheron Hitch during the 1983 Calgary Stampede.

Souvenir plate from the Goderich Township Sesquicentennial 1835 – 1985 featuring Tom Penhale’s Disney World wagon.

2018.0042.001

A Disney Parade

In July 1999, Goderich was the host for the first and only Canadian Hometown Disney Parade featuring Mickey Mouse, friends and characters. There were only 5 cities chosen in North America that year. Doug Fines, who was the President of the Goderich Chamber of Commerce at the time, submitted the winning essay to the contest to host the parade. The essay needed to convey true Mickey community spirit but of course having ancestral roots in Huron County helped as well. The organizers were expecting approximately 50,000 people to line the 2 ½ km route through Goderich. It is estimated that the final number was closer to 100,000.

While the connections between the famed Walt Disney and Huron County are few, their significance is no less meaningful. From ancestral roots to prize winning wagons and parades, it really is “a small world after all”.

by Sinead Cox | Mar 18, 2020 | Blog, Investigating Huron County History

Beth Knazook, Special Project Coordinator for Huron’s digitized newspaper project reviews the bitter rivalry between Huron’s first newspaper editors. You can search the newspapers yourself for free at https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/digitized-newspapers/

The Signal was the first newspaper printed in Huron County, beginning on February 4, 1848. Published in Goderich by Charles Dolsen, and edited by Thomas Macqueen (or “McQueen”), it promised to deliver “as many Essays and as much knowledge on all subjects of practical importance, as our space and time will reasonably allow,” Huron Signal (February 4, 1848), 2.

The Signal was the first newspaper printed in Huron County, beginning on February 4, 1848. Published in Goderich by Charles Dolsen, and edited by Thomas Macqueen (or “McQueen”), it promised to deliver “as many Essays and as much knowledge on all subjects of practical importance, as our space and time will reasonably allow,” Huron Signal (February 4, 1848), 2.

Macqueen was born in Ayrshire, Scotland, where he gained some fame as a poet and an accomplished lecturer. He immigrated to Canada and lived with his sister in Renfrew, Ontario, where he worked briefly as editor of The Bathurst Courier (Perth) before moving to Goderich to take up the position of editor for the Huron Signal. Instead of focusing only on local news, Macqueen brought literature, political, and cultural news from afar to the Western frontier of Canada. In its first issue, he ran articles detailing the history of Cortez’s conquest of Mexico, a travel account of Smyrna, and tales of “The Bushman” living in the Australian outback. He covered scientific news as well, re-printing snippets from other papers containing new information about exciting discoveries like electricity. He also included his own poetry, and encouraged others to contribute poems and songs.

The Huron Gazette began publishing a few weeks later, on February 25, 1848, offering a conservative counterpoint to the Huron Signal’s liberal voice. There are fewer surviving copies of the Gazette from which to piece together the history and contents of the paper, but it seems to have been more practical in its aims. Local advertisements appeared alongside snippets of home and foreign news, dispatches from British Parliament, and editorials – with some entertaining fictional stories thrown in the mix. By late May, the paper had become so popular that editor John Beverley Giles considered either using larger paper sheets or going to a semi-weekly delivery to fit in more content. “We thank our kind supports for the patronage that has demanded from us this alteration, and we think it will evidence to the Province in general the enterprise and intelligence of the Huron Tract,” Huron Gazette (May 26, 1848), 2.

The Huron Gazette began publishing a few weeks later, on February 25, 1848, offering a conservative counterpoint to the Huron Signal’s liberal voice. There are fewer surviving copies of the Gazette from which to piece together the history and contents of the paper, but it seems to have been more practical in its aims. Local advertisements appeared alongside snippets of home and foreign news, dispatches from British Parliament, and editorials – with some entertaining fictional stories thrown in the mix. By late May, the paper had become so popular that editor John Beverley Giles considered either using larger paper sheets or going to a semi-weekly delivery to fit in more content. “We thank our kind supports for the patronage that has demanded from us this alteration, and we think it will evidence to the Province in general the enterprise and intelligence of the Huron Tract,” Huron Gazette (May 26, 1848), 2.

Perhaps a rivalry between the editors of these two papers was inevitable given their political leanings, but Mr. Giles appears to have had a particular talent for provoking the Signal’s Thomas Macqueen. His commentary in the Gazette frequently took the form of very personal attacks, which in turn provoked exasperated and increasingly angry responses in the Signal. Accusations made about the conduct of Mr. Macqueen on the occasion of the annual Agricultural Society’s Show in 1848 prompted several surprised and supportive letters to the editor condemning the malicious gossip in the Gazette.

Thomas Macqueen’s frustration with the Gazette seems to have reached its limit when he declared “We think Mr. Giles is unfortunate in every thing he takes in hand, and still more unfortunate when he tries the pen. His paper will soon be unable to contain his answers to the remonstrances of those he has offended by his impudence. We think he should give it up, —or if not, he should cease to be guided or counselled by those reckless inexperienced characters who are driving him to misery and disgrace for their own vain and selfish purposes, and who lately forced him to insult the respectable community of Goderich under the designation of ‘bare-footed boys and slip-shod girls,’” Huron Signal (May 12, 1849), 2.

Not many issues of the Huron Gazette have survived to explain Mr. Giles’ side of the story, but we do know that in June of 1849, Mr. Macqueen’s predictions about the Gazette’s impending doom were proven right. Mr. Giles abandoned the editorship of the Gazette, although the paper survived a little while longer under editor(s) who seem to have wanted to keep their names hidden. The Huron Signal reported at one point that “nobody is the Editor of it, and nobody will take the responsibility of it. It is not read by 50 men in the District of Huron, and of that fifty, there are not five who attach the slightest credit to any of its statements,” Huron Signal (June 22, 1849), 2. When the Gazette ceased publication in 1849, Mr. Giles left town – but not the newspaper business. He would take up the editorship of the St. Catharines Constitutional, hopefully with better results.

Inkwell used by Thomas McQueen. 1978.10.1. Collection of the Huron County Museum.

Macqueen edited the Signal until his death in 1861 at the age of 57, at which point J.W. Miller took over as editor while the publishing side was managed by Macqueen’s son-in-law, T. J. Moorhouse. The paper was then sold to William T. Cox, who ran it until 1870, and from there it changed hands many more times over the years. The Huron Signal survives today in the form of the Goderich Signal Star. Over the course of the paper’s long history, there has been a lot more (friendly) competition in the Huron County weekly news business.

by Sinead Cox | May 18, 2017 | Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

May 18th is International Museum Day! Museums and historic sites across the world are opening their doors for free today. For those whom cannot visit the Huron Historic Gaol in person, Student Museum Assistant Jacob Smith delves into the building’s past to reveal how some of Huron’s youngest prisoners ended up behind bars.

During its operation [1841-1972], hundreds of children were arrested and sent to the Huron Jail. Their crimes ranged from arson and theft to drunkenness and vagrancy. The most common crime that children committed was theft. In total, thefts made up over half of all youth charges between 1841 and 1911. In total, children under the age of 18 made up 7% of the gaol population during that time.*

Occasionally, young people were sent to gaol for serious crimes. In 1870, William Mercer, age 17, was brought to the Huron Gaol and charged with murder. He was sentenced to die and was to be hanged on December 29, 1870. Thankfully for Mercer, his sentence was reduced to life in prison and was sent to a penitentiary. This is an example of an extreme crime for a young offender.

On many occasions, children were sent to gaol because they were petty thieves. Many young people who were committed for these types of crimes would only spend a few days in gaol. If the crime was more severe, children would be transferred from the gaol to a reformatory, usually for three to five years.

The youngest inmates that were charged with a crime were both seven years old. The first, Thomas McGinn, was charged in 1888 for larceny. He was discharged five days later and was sentenced to five years in a reformatory. The second, John Scott, was charged in 1900 for truancy; he was discharged the next day.

First floor cell block at the Huron Historic Gaol.

Unfortunately, some children were brought into gaol with their families because they were homeless or destitute. An example of this was in 1858, when Margaret Bird, age 8, Marion Bird, 6, and Jane Bird, 2, spent 25 days in gaol with a woman committed for ‘destitution’ (presumably their mother). Some children were also brought to the Huron Jail because their parents committed a crime and they had nowhere else to go while their parents were incarcerated. Samuel Worms, age 7, was sent to gaol with his parents because they were charged with fraud in 1865. He spent one day in the Gaol.

When reading through the Gaol’s registry, it is clear that times have certainly changed for young offenders. Most of the crimes committed by the young prisoners of the past would not receive as serious punishments today.

Here are some examples of their crimes in newspapers from around Huron County:

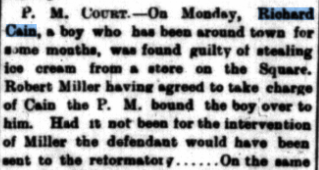

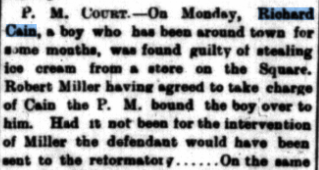

Richard Cain, 16, spent two days in jail.

The Huron Signal, 1896-09-17, pg 5.

Philip Butler, 15, spent eleven days in the Huron Jail.

The Exeter Advocate, 1901-08-29, pg 4.

Sources came from the Gaol’s 1841-1911 registry and Huron County’s digitized newspapers.

*Dates for which the gaol registry is available & transcribed. There were young people in the Huron jail throughout its history, into the twentieth century.

by Sinead Cox | Oct 20, 2016 | Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

“Is this place haunted?”: it’s one of the most common questions fielded by front desk staff at the Huron Historic Gaol. I’ve never set eyes on a ghost myself, but at least fifty-eight prisoners at the Huron Gaol died during their imprisonment. The jail’s four-cell-block design was intended for short stays—prisoners with multi-year sentences received transfers to larger institutions like Kingston Penitentiary—but for some Huron County inmates, theirs was indeed a death sentence in practice. Whether or not prisoners choose to revisit the grounds as ghosts, the recently launched online repository of Huron County newspapers has made it a little easier to research and shed light on their lives and deaths inside the Huron jail.

The Signal, 1911-6-15, pg 1

Infamously, three men—all under the age of thirty—hanged for murder at the Huron jail in Goderich: William Mahon in 1861, Nicholas Melady in 1869 (Canada’s final public hanging) and Edward Jardine in 1911. Although these are perhaps the best remembered demises at the jail, executions were rare and not representative of the fifty-eight known inmate deaths that took place here before 1913, the vast majority of which were the result of natural causes like old age and disease. The average age of deceased prisoners was sixty-three. The oldest inmate to die in the jail with a recorded age—often merely an estimate by the gaoler or gaol surgeon—was approximately ninety; the youngest fatality was a two-month old infant named Robert Vanhorn who had been committed with his young, unmarried mother in 1879.

The Signal, 1884-2-29, pg 2

Most of the inmates who died in the jail were in fact not criminals at all, but elderly persons committed as ‘vagrants’ because they were homeless, or too frail and sick to provide for themselves. Some were itinerants, but many were long-term Huron County residents without friends and family able to support them in their old age. Unmarried, widowed or childless labourers and domestics were especially vulnerable, as well as early settlers whose closest relatives still remained in the old country. When Seaforth servant Margaret Ainley died in the jail of typhoid fever in 1883, The Huron Signal reported that “her relatives live in England.” Eighty-one-year-old Matthew Shepherd, a native of Scotland and a veteran non-commissioned officer of Her Majesty’s 93rd Foot, had seen service in the West Indies as well as British North America; the veteran soldier was a resident of Ashfield Township for three decades when he died in jail, but “had no direct relatives in this country” according to a June, 1891 obituary in The Signal. Both Ainley and Shepherd’s committals had been for vagrancy.

Other prisoners suffered from mental illness, dementia or serious health problems that their families could not cope with. Seventeen-year-old Patrick Kelleher, for example, had exhibited symptoms of mental illness or developmental issues since his childhood. His parents were newly arrived Irish emigrants in the summer of 1883, when the strain of caring for him evidently became too difficult and he was committed to the Huron jail for insanity. Patrick died there of a seizure in January, 1884 while still awaiting transfer to the Provincial Asylum.

The Exeter Times, 1875-12-30, pg 1

Without a safety net of organized social services, responsibility for Ontario’s rural poor fell to local municipalities in the nineteenth century. Sometimes the needy received assistance in their own communities and homes, but the gaol was one of the earliest municipal buildings with a full-time staff, and provided a convenient location for local governments to clothe, feed and supervise these ‘wards of the county.’

Starting in the late 1870s, Joseph “Big Joe” Williamson faced repeated committals to the Huron jail for vagrancy-a common pattern for homeless prisoners who had nowhere to go when their sentences ended. A Huron Tract ‘pioneer,’ seventy-four-year-old Williamson was a former contractor and once-prominent figure in local politics—so gifted at storytelling that he was called ‘Huron’s bard’. He petitioned County Council’s gaol & courthouse committee to transfer him to a hospital in December, 1883. The committee subsequently recommended that he be removed to the Middlesex County Poor House, but instead “Big Joe” died of heart disease at the Huron Jail on January 14th, 1884. The Huron Signal’s obituary deemed Williamson’s fate a “misspent life…after a tendency to drink and a liking for conviviality brought him down to penury.”

The Huron Signal, 1884-3-21, pg 4

In the absence of a House of Refuge in Huron County, the jail became a de facto poorhouse, hospital, lying-in-hospital for unwed mothers and long-term care home. The jail staff*—consisting in the nineteenth-century of the gaoler, the matron (his wife or eldest daughter), the turnkey, gaol surgeon, and any servants or family members who lived on site—provided frontline care to the old and sick in addition to their duties of managing the gaol and guarding actual criminals. In 1884, when William Burgess, an inmate from Brussels with cancer in his leg, lay slowly dying in his jail cell, Jailor William Dickson and turnkey Robert Henderson took turns keeping a nightly vigil on the ward he occupied with another sick inmate. This cell-mate, Johnny Moosehead, had actually helped to nurse Burgess himself before he became too ill with erysipelas. Fellow inmates quite often helped the gaol staff provide the constant care needed for elderly or dying prisoners. In the case of George Whittaker, a seventy-year-old Brussels ‘lunatic’ who died in July 1881 of self-inflicted injuries, the gaoler also charged the man’s ward-mates to help provide vigilance against self-harm—unfortunately to little avail.

A formal coroner’s inquest with a jury of prisoners and citizens was mandatory for every inmate death. After the death of ninety-year-old ‘indigent’ Hugh Hall in April 1887, friends of his from the Clinton area sent a hearse to Goderich to claim the body for a proper funeral, but a holiday delayed the inquest and the hearse had to return to Clinton empty until the coroner and jury could be assembled. The ‘usual verdict’ of these inquests was ‘natural causes’; over a dozen inmates had their cause of death simply recorded as some variation of ‘old age’ or ‘senile decay’. Testimony at these inquests, however, afforded the gaol staff, including the gaoler, matron and gaol surgeon, an opportunity to decry the gaol’s tragic inadequacy as a home for the insane or terminally ill.

The Signal, 1891-10-16, pg 1

The plight of the jail’s long-term residents did not go completely unnoticed or forgotten by the rest of the county, as gaol staff, inquest juries, newspaper editors, and successive jail and courthouse committees demanded better care for Huron’s poor. Public reports of the Gaol and Court House Committee had recommended transferring both Matthew Shepherd and William Burgess to a poor house before their deaths. An 1884 editorial in the Huron Signal called for County Council to be ‘indicted for murder’ for neglecting to build a House of Refuge to shelter the poor in Huron County after decades of discussion. In October, 1891 the same newspaper ran an exposé on the lives of the old and sick inside the jail, describing the circumstances of each individual inmate, and lamenting the injustice that these individuals would soon perish in jail. For at least three of the prisoners profiled in that piece, this sad prophecy swiftly came to pass: octogenarian Mary Brady would die after being bedridden with a broken arm only a few months later, the blind and ill John McCann would pass away in less than a year, and John Morrow—committed 25 times for vagrancy before his death—died of heart failure exacerbated by choking in 1893.

The Signal article pronounced that the vagrants of the Huron County Jail were doomed to a ‘criminal’s funeral’-but what this entailed varied case by case. Although their fates may have been sadly predictable, the final resting place of the jail’s dead is sometimes unclear. Some, like Hugh Hall, had friends, neighbours, clubs or family members who claimed their loved ones’ bodies and paid funeral expenses; this appears to be the case for all three executed men. Despite reported rumours that victim Lizzie Anderson’s mother had asked for his body to inter beside her daughter’s, hanged murderer Edward Jardine, for example, received burial at Colborne Cemetery per his request. If no claimants came forward for a deceased ‘vagrant’, however, interment became more uncertain. The Exeter Times reported at least one prisoner, James Stinson of Hay Township, as being buried in a ‘Potter’s field’ in 1878-referring to an unmarked grave or ‘pauper’ section of a cemetery.

The Huron Signal, 1887-06-03, pg 4

By the 1880s regional Anatomy Inspectors were responsible for ensuring that unclaimed bodies were not buried at all, but instead sent to medical colleges for dissection and research. In 1895, Colborne Township’s Elizabeth Sheppard perished at the jail of ‘senile decay’; according to the Wingham Times, Goderich undertaker and county Anatomy Inspector William Brophey was preparing Sheppard’s body for conveyance “to Toronto for some use in the colleges,” when at the last moment a brother materialised to retrieve her for burial in Goderich.

The Exeter Advocate, 1894-06-07, pg 8

Instances of cadavers from the Huron County Jail successfully reaching Toronto medical students are unconfirmed***, but this would have followed the law. Huron County finally successfully constructed a House of Refuge in Tuckersmith Township in the 1890s, which has since evolved into the Huronview home for the aged. Today there is a monument to the residents buried there, but at the turn-of-the-century these interments at the House’s farm property were actually in conflict with legislation. By 1903, Keeper Daniel French had to be publicly reminded of the laws respecting the disposal of bodies at government institutions—all cadavers were supposed to be transferred to the regional Inspector of Anatomy within twenty-four hours if no ‘bona fide friends’ appeared to claim a corpse. French was liable for a $20 fine, but the current Huron County Warden advised him to continue burials. Local jailers, however, may have been more law-abiding.

Knowing that most deaths at the Huron Historic Gaol were due to long and lonely incarcerations caused by old age and infirmity, it’s hard to imagine many of these men and women returning to haunt the narrow corridors. They served virtual life sentences as an unfortunate consequence of poverty and isolation, and any added time in the afterlife seems undeserved. I don’t know if you can find the ghosts of the likes of Mary Brady or William Burgess stalking the courtyards after dark, but the reports of inmate interments we do have indicate that you can find the jail’s dead in cemeteries across Huron County, including those located in Hensall, Clinton, Seaforth, Brucefield, St. Columban, Goderich, Blyth, Dungannon, and Colborne. At the very least, the jail provides another place to remember and reflect upon the lives of the others, whose graves are unmarked and unknown.

*Living onsite meant that gaoler, matron and family members also sometimes breathed their last on site, including former matron Ann Robertson, Gaoler Edward Campaigne, and two young daughters of Jailer Joseph Griffin

***Since this post was published, further research using The Brussels Post newspapers has confirmed that at least two Huron inmates were sent to medical colleges for study: Mary Brady and William Shaw. Shaw’s son had requested that his father be buried in Howick Township, but couldn’t provide the funds himself.

Research for this blog post used historical newspapers made available via Huron County’s Newspaper Digitization project, as well as the gaol registry 1841-1911 and transcribed coroner’s reports available at the Huron County Archives Reading Room, Huron County Museum.

Start searching through online historical newspapers today to learn more secrets of Huron’s past!

by Sinead Cox | Aug 25, 2015 | Huron Historic Gaol, Special Events

The Huron Historic Gaol’s popular evening Tuesday and Thursday tours, Behind the Bars, are coming to an end for another year! Your last chance to meet historic prisoners and staff from the gaol’s past is Thursday, August 27th at 7-9pm. In celebration of another successful season, Colleen Maguire, one of Behind the Bars’ veteran volunteer performers, gives readers a behind-the-scenes glimpse of what it takes to get into character and travel back to the gaol’s past every Tuesday and Thursday evening in July and August.

It is Thursday again and in a few short hours I will walk back into the 1890s. That’s because I portray Mrs. Margaret Dickson in the Behind the Bars tours at the Huron County Gaol, Goderich.

These Behind the Bars Tours feature about 18 actors who portray real people who lived, worked and were inmates of the Gaol, now a National Historic Site.

Mrs. Dickson became the Gaol Matron aka Governess when her husband William became the Gaoler in 1876. Together the couple raised five of their own children while living and working in the gaol. This is my third year portraying this beloved matron. I have researched countless hours to learn everything I can about her and her husband. At any given moment I must be able to answer any question posed to me by the public and be able to accurately answer their queries as if I were Mrs. Dickson. Do come for a Behind the Bars Tour and hear the rest of the remarkable story.

With the research aside how does someone physically prepare for their role in Behind the Bars?

It’s an hour and 15 minutes before the big doors of the Gaol will open to admit the curious so they can relive the history and the people of the Gaol where the 21st century literally collides with the 19th century.

[Physical] preparation for my role began months ago when I began growing my hair. The gaol is hot and [after] two [previous] seasons sweltering while wearing a wig it was time to try something different with my [short] hair. By growing it long enough I am able to pin an artificial matching hairpiece bun on the back. Now with a bit of practice, I can take my hair from a modern style to one befitting an older matron in the late 1800s. Mrs. Dickson was 67 years old in the year I portray her.

Before and After: Volunteer Colleen Maguire transforms into Mrs. Margaret Dickson, gaol matron.

The process begins by trading my t-shirt for a 100% cotton camisole. I learned early on to remove any over-the-head garments before starting the hair. Based on a photograph of Mrs. Dickson from this time period I know that she had white hair, parted in the middle and pulled to the back. My own hair is white, but naturally wavy, so getting the right look requires using some hair wax, twenty-one bobby pins and a lot of hairspray.

While the hairspray dries, it’s on to the next phase. Black stockings, then long pantaloons with a drawstring in front that have to be tied with a double knot, as they have been known to come undone resulting in a potentially embarrassing wardrobe malfunction. I then step carefully into my crinoline rather than take it over my head. The most common mistake that women reenactors make is not having the proper underclothing so that their dress or skirt can hang properly and fully. By now my hair should be fairly lacquered into place, so it’s time to attach and pin the bun hairpiece on and remove some hair pins now that the hairspray has taken over. A quick glance at the clock tells me that I have approximately 15 minutes left.

It’s a hot July day, so I grab my spray bottle and mist my cotton camisole with cool water, just enough to be wet through but not wet enough that my next item of clothing– my high collared, long, full sleeved Victorian working blouse–will become wet. I carefully guide and slip the floor-length long cotton twill skirt over my head. The Victorians were so smart, the closure on the back of my shirt allows me to button it at three different waist sizes. A little shake and my shirts fall into place. Next I clip my pewter Chatalaine to my skirt waistband; on its four long chains hangs two small keys- one for my writing desk and the other for Dr Shannon, the Gaol surgeon’s medicine cabinet, a pencil, small scissors and a quarter-sized timepiece. Pinning an antique cameo pin on the front of my high collar, placing a wedding band on my finger, and putting on my pince-nez eyeglasses, the final glance in the mirror indicates the transformation is complete. With my driver’s licence tucked into the lining of my antique purse, I set off for the car. Here is where history collides, for getting into a compact car with long skirts and lots of clothing is a bit tricky. You don’t want to be driving down the street with an article of clothing sticking out of your car door.

The matron’s keys: part of Colleen Maguire’s Behind the Bars costume.

Once at the Gaol I climb the spiral staircase to the second floor Gaoler’s Apartment just as Mrs. Dickson would have done countless times. This is where the Gaoler and his wife and all their children lived. Well, that and a smallish cottage built in one of the courtyards of the Gaol in 1862. What about the Governor’s House [a two-storey home attached to the gaol] you ask? Well that wasn’t built until 1901, long after Mrs. Dickson had passed on in 1895.

Mrs. Dickson was prolific letter writer, whether it be asking for a raise or writing letters asking for a House of Refuge to be built in Huron County. She was a social worker long before it was a fashionable career for women. Consequently, I have chosen to use as my props a small writing desk, ink well, and nib pen. Each night I slip my black cotton sleeve protectors on and begin the task of writing grocery lists, and other letters. Sometimes I surprise the [other] actors by reading to them a letter from their family that I have crafted or handing Dr. Shannon [the gaol surgeon] a note about an newly admitted inmate. It’s all part of the improv that takes place throughout the evening.

It’s 7 PM and the big Gaol doors have opened and in have flooded the tourists anxious to experience what life is really like in a 19th-century Gaol.

“Please allow me to introduce myself. I am Mrs. William Dickson, the Gaol Governess.”

Need to know more about what goes on behind the scenes at Behind the Bars? Check out coordinator Madelaine Higgins’ earlier post about planning the event.

Do you want to volunteer at the Huron County Museum or Huron Historic Gaol? To learn more about the Friends of the Huron County Museum, email museum@huroncounty.ca