by Amy Zoethout | Mar 29, 2021 | Media Releases/Announcements

Don’t miss out on seeing Reflections: The Life and Work of J.W. (Jack) McLaren, on at the Huron County Museum until April 30, 2021.

Praised by visitors as an “amazing show” featuring “spectacular” art and an “interesting slice of Huron County and beyond”, Reflections has drawn repeat visitors since opening at the Museum in October, 2020. The exhibit explores McLaren’s prolific career as an artist, illustrator, and performer, and features close to 100 pieces of his art on loan from the community.

Presented in partnership with the Huron County Historical Society, Reflections not only shares an incredible local collection of art, but also looks back on McLaren’s fascinating life, including his time in World War I where he performed as a member of the Dumbells Comedy Troupe, and his membership in the Toronto Arts and Letters Club where he became associated with the Group of Seven.

For those unable to visit the exhibit in person, the Huron County Museum will be hosting Jack McLaren: A Soldier of Song, a virtual event that can be enjoyed from home on April 9, 2021.

This event will feature a presentation and performance by Jason Wilson, musician and author of Soldiers of Song: The Dumbells and Other Canadian Concert Parties. Wilson’s performance is based on the original works of the Dumbells, a Canadian concert party that entertained the troops on the front lines in World War I and featured Jack McLaren.

To register for this event, or to explore more ways to enjoy the Reflections exhibit from home, visit: https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/reflections/

The public is invited to book a visit to catch the exhibit by calling 519.524.2686. The museum is open from 10:00AM-4:30PM on Tuesday, Wednesday and Friday, 10:00AM-8:00PM on Thursday, and 1:00PM-4:30PM on Saturday. Reflections is included with regular admission, or free for museum members and Huron County Library cardholders.

by Amy Zoethout | Mar 13, 2021 | Artefacts, Blog, Collection highlights, Textile Collection

Above: Herb Wheeler’s Carpentry Shop in Belgrave, ON. Herb is seen standing in front (Photo courtesy of Richard Anderson).

Guest blogger Sharlene Young-Bolen, of Stitch Revival Studio in Blyth, shares more about how a Huron County Museum artifact inspired her to create the Huron Wristers pattern and how her research into the origin of the pattern led her to connect to family of the original owner. The original gloves are currently on display in the Museum Gift Shop where Sharlene’s Huron Wristers kits are also available for purchase.

Was there a Wheeler family tie to either Estonia or the British Isles? The answer would help to identify the glove pattern perhaps. When an Instagram post by Best Dishes, a Goderich business owned by Sarah Anderson, appeared in my feed one day identifying the wristers pattern as based on a family heirloom, chance had dropped the perfect opportunity. It was time to connect. A couple messages back and forth and the story unfolded…

The Charles Wheeler Family circa 1900. Back: Carrie, Herb, Ernest. Centre: Charles, Cecil, Jesse, Lennie, Mary Ann; Front: Lena, Myrtle (Photo courtesy of Richard Anderson).

Sarah, as it turns out, is the daughter of Richard Anderson, great-nephew of Herbert Wheeler, the original owner of the gloves. Richard sent the following information about the history of the Charles Wheeler Family:

Charles Wheeler Sr. was born in Dorsetshire, England and came to Canada in 1846, locating in Tecumseh Township where he spent 18 years. In 1864 he moved with his family to Morris Township where he bought 300 acres which would be the N ½ of Lots 10, 11 and 12, Concession 5, more commonly known as the 4th Line. He married Caroline Lawrence and they raised a family of five sons, Charles, John and Lawrence of Morris Twp., William of Alma, Frank of Belgrave, and a daughter Mrs. Ann Hughes of Escanaba, Michigan.

Charles Wheeler Jr. married Mary Ann Wilkinson and they raised a family of five sons, including Herbert, and three daughters. Charles farmed on Lot 12 and after his death in 1913, his son Jesse took over the home farm. When Jesse married, his mother moved to Belgrave to the house now occupied by Wes and Annie Cook. Jesse continued to farm there until he retired to Belgrave.

The Charles Wheeler Family, standing in birth order; youngest to oldest, L-R Myrtle, Lena, Cecil, Jesse, Lennie, Ernie, Herb, Carrie (Photo courtesy of Richard Anderson).

Herbert married Pearl Procter. They lived in Belgrave and had three children: Goldie, who married Winnie Lane and lived in London; Velma married Wilfred Pickell and lives in Vancouver; Ken married Mabel Coultes and farmed in East Wawanosh before retiring to Belgrave. Herbert had a woodworking shop in Belgrave.

Herbert’s grandson David Pickell, recalls: “When I knew my grandparents, Pearl and Herb, they lived in Belgrave. Herb Wheeler was a carpenter and, as the name suggests, repaired farm equipment such as wooden wheeled carts etc. He was quiet, and had a subtle sense of humour us kids loved.”

The following poem was written about Herbert Wheeler by a family member and gives a wonderful, lasting impression of just who Herbert was and his occupation as a talented woodworker, carpenter and barber. It would have been great to experience just what this writer did so long ago.

Herb Wheeler’s Carpentry Shop & Hair Cutting CIRCA 1932-1945

Whenever Herb was in his shop, I’d like to go and look,

He might be cutting some one’s hair, or be reading some big book,

There were jigs galore hanging all around, some maybe for a sleigh,

There were shavings bright upon the floor, they would soon be swept away.

Herb never left a job undone, if he could finish it that day,

Except of course a larger job, he would maybe stop and say,

“Tomorrow is another day, I’ll hope to get it done,”

“But if I don’t the job will keep, it’s not hurting any one. ”

Sometimes just after Supper, Herb again would be around,

He’d pump up a gas lantern, light it up and settle down.

For Herb, doubled as a barber, he’d cut hair two weekday nights,

Herb, never used power clippers, he did not charge enough by rights.

Somehow, Two bits is what I think, was all a haircut cost,

I really can’t remember, it’s something I have lost.

Herb did not pull your hair at all, as hand clippers often do,

He’d sometimes talk as the clippers clicked, and he’d ask, “does this suit you” ?

Herb was skilled at doing wood work, he could make most anything,

He made a Bob sled for the kids, it nearly did take wing.

The fastest sled around those parts, down the ninth line hill it flew.

Ken would try to give us all a ride, or sometimes maybe two.

I expect that Goldie used the sled, and likely Velma too,

It needed someone that could steer, and knew just what to do.

I’ve seen the times, when snow was hard, and a fast start at the top,

You’d have to turn the corner, at the highway, to get stopped.

Herb made Ken skis, that were Black Ash wood, what a lovely pair,

The skis would take you down a hill, like you were cushioned on some air.

When the skis were waxed and shone and dried, no one ever saw the like,

They would make a run ahead of all, they would go clean out of sight

There were other things of super class, that emerged for that shop door.

A set of kitchen cupboards, like you’d never seen before.

Herb had a little saying, and he practiced it always

“If you measure twice before you cut, it eliminates delays”!

I have seen him make a set of shafts, the wood he’d have to steam

To make a bend for the horse to fit into the cutters beam.

Herb had the kind of patience, that a lot of people lack,

That is what made him extra special, with an extra special knack.

So far, the research has yielded no straight answers as to the gloves’ origin, but the search continues. While a pattern might give you a hint to the origin of a knitted item, you need to identify more, such as the cast-on method, the type of ribbing, how the fringe was made, and how the strands (or floats) were carried across the back of the knitting. A full reproduction of Herbert’s gloves would help to answer the remaining questions.

In conclusion, there really isn’t a conclusion… But what I can say is that taking the time to explore knitting traditions and a local family’s history has been a fascinating, rewarding experience. I’m so grateful for Herbert’s relatives who have answered my questions and sent so many wonderful images to be shared here with everyone. They went to a lot of work to compile the info and family photographs and I can’t thank them enough for all their time and effort.

I’ve come to think that the original knitter may have incorporated features that he liked into these gloves, perhaps not following one certain pattern, but rather combining different elements into one. A full recreation of the gloves is planned for late fall 2021 and right now I’m testing a local wool I may be using for the reproduction. Stay tuned to the website for further updates as we move forward.

Learn more:

by Amy Zoethout | Mar 11, 2021 | Collection highlights, Textile Collection

Guest blogger Sharlene Young-Bolen, of Stitch Revival Studio in Blyth, shares more about how a Huron County Museum artifact inspired her to create the Huron Wristers pattern and how her research into the origin of the pattern led her to connect to family of the original owner. Sharlene will be joining us March 25 when she will lead a virtual workshop to teach participants to make the Huron Wristers. The original gloves are currently on display in the Museum Gift Shop where Sharlene’s Huron Wristers kits are also available for purchase.

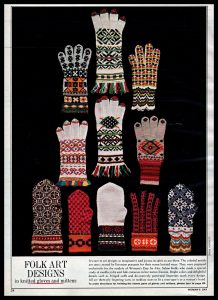

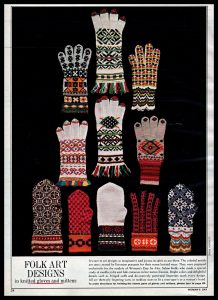

The knitted glove once owned by Herbert Wheeler.

The story of the creation of the Huron Wristers is a story of connections: the connection of past to present, of generation to generation.

Back in 1972, Pearl Wheeler donated a pair of knitted gloves that once belonged to her husband Herbert to the Huron County Museum and Historic Gaol. The museum’s record notes that at the time the gloves were thought to date from 1870 and were knit by a man.

Herbert and Pearl lived in Belgrave, ON. Herbert had seven siblings, four brothers and three sisters. His parents were Charles Wheeler and Mary Ann Wilkinson. Herbert was a carpenter and apparently also the local barber. How long the gloves were in Herb’s possession no one knows.

While visiting the museum to research women’s headcoverings – I had an idea to recreate a head scarf worn by one of my ancestors – I happened upon an image of Herb’s gloves. There was something very intriguing about the gloves. First, the colours – the pink is very bold and the contrast between the pink and black is quite striking. Secondly, the colourwork pattern – it seems familiar, but yet different somehow. It looks Fair Isle-inspired, but there’s something else there. And the fringe of the cuff, so interesting.

The Huron Wristers, inspired by the colourwork in Herbert’s knitted gloves.

Who made these gloves? There’s no record of that. The gloves may have been knitted for Herbert by an older family member; or purchased at some point earlier on and then Herbert inherited them; or Herbert bought the gloves himself from someone; or given his trade, perhaps they were payment for some work he did. It was time to do research on the pattern and see what could be found.

Herbert’s gloves were knit in the round using the stranded colourwork technique, working two colours of yarn in the same row, carrying the unused yarn across the inside of the work. The 8-stitch motif repeating pattern is similar to both the Shetland Fair Isle knitting pattern, ‘Little Flowers’ as well as an Estonian pattern called, ‘Cat’s Paw’.

The gloves feature a knitted fringe on a short ribbed cuff. Fringing has been used on both Latvian mittens and Estonian gloves, historical and modern versions and not so much in the Fair Isle tradition. The fringe appears to have been done using a loop technique which is done during the construction of the glove. The colourwork may seem close to the Sanquhar tradition, but it’s not a match for the following reasons according to knitters on the Knitting History Forum:

- There are quite a few designs associated with Sanquhar. Possibly the most well-known ones are based on 11 by 11 stitch squares. The squares have strong outlines with alternating patterns within the squares. Herb’s gloves therefore do not fulfill these criteria.

- Some Sanquhar gloves also have an interesting finger construction with little triangular gussets in the finger spaces and triangular finger tips. Also, all Sanquhar have a shaped thumb placed on the palm side rather than on the side of the hand as here.

- Finally, the stitch count, wool and colour are not really in the Sanquhar tradition. Gloves tend to be monochromatic. Wool used is finer, stitch count for the cuff around 80 stitches and modern needle size of around 2mm used.

The Knitting History Forum was invaluble as it connected me with Angharad Thomas, researcher, designer and knitter. Angharad wrote, “The only pattern I could find similar to that used in these gloves was a 4 stitch x 4 row triangle in a Shetland pattern book … but there’s a limit to what can be knitted on a given number of sts in whatever colours are to hand. That’s how I think these patterns came about rather than from one tradition or another. Fringes are now associated with Latvia but there are gloves from the north of England with a fringe…” Angharad then suggested I reach out to Shirley Scott, Canadian knitting designer and author.

Traditional Estonian gloves and mittens showing the beautiful colourwork and fringed cuffs.

Scott immediately suggested the similarity to Estonian mitten patterns and sent a few images of pattern motifs. She then pointed me in the direction of Nancy Bush, an Estonian knitting expert. Shirley also cautioned that there may be no clear and definitive answer as to the pattern name and origins.

“Don’t be surprised if the pattern has no real name. Newfoundland patterns have never had names, for example. We made ours up, as explained in our books. It’s also hard to pinpoint the origins of patterns these days because North America has had so many waves of immigration and so much pattern sharing,” said Scott.

Nancy Bush, a knitting writer, designer and authority on Estonian knitting, wrote:

“I have found a pattern close to the one on your mittens from both Paistu and Helme parishes in Estonia (these are southwest). The difference is that the diamond with cross shapes are offset, as is the example of Sander’s Mittens in Folk Knitting in Estonia. There is another pattern that is like the ones from Helme and Paistu in a pattern book from the Rannarootsi Museum in Haapsalu. This museum tells the story of Swedish/Estonian people who lived in Estonian territory, mostly until the 2nd WW. I don’t know the story of these exact mittens, just that the pattern is close.”

Estonian Mitten Pattern by Nancy Bush. The repeating motifs are almost a match for Herbert’s gloves, but for the fact they are offset, nested within each other, not point to point.

Bush continued, “The fact that the diamond with cross shapes are stacked instead of offset makes me think they were not looking at any of the patterns I have mentioned above, or mittens made like them…

All that being said… this is a very simple pattern, easy to create with knit stitches and could have originated almost anywhere… it is very possible these mittens were made by someone who was remembering a pattern they knew as a child, for instance, and reproduced it as best they could, with the yarn they had…”

So, which was it, Estonian or Fair Isle? It was time to research the Wheeler family and Herbert. Where did their family originate? Was there a family tie to either Estonia or the British Isles? When an instagram post by Best Dishes, a Goderich business owned by Sarah Anderson, appeared in my feed one day identifying the wristers pattern as based on a family heirloom, chance had dropped the opportunity in my lap. It was time to connect. A couple messages back and forth and the story unfolded…

Learn more:

by Sinead Cox | Mar 3, 2021 | Artefacts

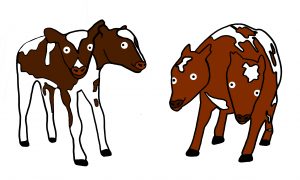

Take a closer look at the Huron County Museum & Historic Gaol and its collections as staff share stories about some well-known and some not-so-well-known features, artifacts, and more. The Huron County Museum’s two-headed calves are perhaps our most recognizable artifacts, and attract a lot of questions from visitors.

Although familiar with the two-headed calves’ history, Acting Senior Curator Sinead Cox wanted to know more about the genetic causes of polycephaly: the condition of a single animal having more than one head. How and why does this rare phenomenon happen?

Sinead talked to veterinarian Dr. Alaina Macdonald to find out more from an expert on animal health.

Sinead Cox: Can you share a little bit about yourself and your professional background?

Dr. Alaina Macdonald

Dr. Alaina Macdonald: I graduated from the Ontario Veterinary College in 2019 and have worked in mixed animal practice since graduation. I have always carried an appreciation for agriculture, and love being able to help animals and their humans live healthy lives. My newest interest is learning how to incorporate aspects of human, animal and environmental health in problem solving of worldwide issues.

SC: The Huron County Museum has two taxidermied calves in our collection with two heads and two tails. How on earth does an animal end up having two heads?

AM: The rare development of two-headed offspring is directly related to the formation of identical twin embryos early in the pregnancy. This phenomenon is seen in reptiles, birds, amphibians, and mammals (including humans). In fact, much of what we know about two-headed animals can be better understood by studying human conjoined twins, as it is a very similar process! When an egg becomes fertilized, a tiny embryo is formed. Occasionally, the embryo divides in a way which produces a second embryo with the same genetic material. This process must occur in a very delicate and specific balance of gene expression and the correct environmental conditions. Most often, it occurs before day 10 of gestation, and the result is two identical twins. Rarely, this process occurs late (around day 13-14), and the process of mitosis (cell division) is interrupted, resulting in two identical embryos which did not fully divide. Some literature indicates that polycephaly is due to a disruption of the primitive streak, which is an organized embryonic structure of cells present towards the second week of gestation.

SC: Could there be environmental factors that would cause this?

AM: No one knows the exact mechanism behind the abnormal splitting of the embryo. Trace mineral deficiencies and environmental factors such as increasing water temperatures and toxin exposure have been implicated in some species, but there are likely many causes. Anything that disrupts that delicate timing of gene expression (including random chance) can cause abnormalities in embryonic development.

SC: How often does this happen?

AM: There is no way to truly know how often this occurs, as this event would generally result in the early loss of pregnancy, and those pregnancies often are undetected. Indeed, it is exceptionally rare for the embryo to develop into a full-term fetus, and to survive the length of the gestation. It is not considered an inherited trait, because the offspring almost never live to reproductive age. In humans, development of identical twins is not considered genetic, which would also indicate that polycephaly in animals and conjoined twins in humans is a “chance” event with possible implications for environmental factors.

SC: Wow. That really puts into perspective how rare and special these calves are. Both of the calves at the museum were born in the early twentieth century. Is polycephaly more likely to happen now than in the past?

SC: Wow. That really puts into perspective how rare and special these calves are. Both of the calves at the museum were born in the early twentieth century. Is polycephaly more likely to happen now than in the past?

AM: Interestingly, fossil evidence indicates that polycephaly has been present in some species for the last 150 million years!

SC: I always think it’s sort of lovely that our two-headed calves are so loved and live on forever at the museum, when they had very short lives (less than a day). Why doesn’t a two-headed calf live very long?

AM: Calves with two heads often have many other congenital abnormalities. For example, the cardiovascular, neural and digestive systems may be malformed, which makes it nearly impossible for the calf to carry out normal vital functions. A live birth of any two-headed animal is rare, and many of them die shortly after birth. There was one calf who survived with intensive care for several months, which is likely the longest any polycephalic calf has lived.

SC: Have you ever seen any two-headed animals in your work life?

AM: No, I have never seen a two-headed animal myself. I am sure it comes as quite a surprise to everyone involved! There is some evidence to suggest that the many-headed creatures described in Greek mythology may have been inspired by polycephalic animals observed during those times.

SC: What is the strangest or most unexpected thing you have seen as a veterinarian?

AM: I have seen some animals in strange predicaments; from the kitten who ate pieces of a couch, to the dog with a piece of tooth embedded in his leg and the cat with a fishhook in his lip, all had something to teach me about veterinary medicine. The most startling moment of my career was when I was standing beside a horse, taking her temperature, and as we stood looking out the barn door the farm was struck by lighting! Everyone was fine, but the farmer needed to replace his electric fence. Nature always has a way of surprising us!

Thank you to Dr. Alaina Macdonald for answering our questions and making us appreciate the uniqueness of these unforgettable artifacts even more! For more information on polycephaly, Alaina suggests these references:

Thank you to Dr. Alaina Macdonald for answering our questions and making us appreciate the uniqueness of these unforgettable artifacts even more! For more information on polycephaly, Alaina suggests these references:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15278382/

http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20161018-the-two-headed-creatures-that-may-have-inspired-hydra

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2016/11/two-faced-calf-lucky-becomes-oldest-on-record/#:~:text=A%20young%20cow%20calf%20with,a%20farm%20in%20Campbellsville%2C%20Kentucky.

FURTHER READING: