by Sinead Cox | Jan 25, 2022 | Archives, Exhibits, Image highlights

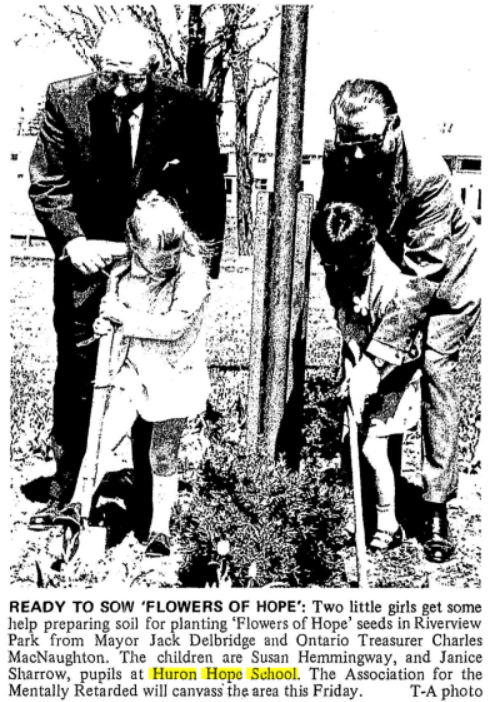

The Huron County Museum’s temporary exhibit Forgotten: People and Portraits of the County features unidentified portraits captured by Huron County photographers. In addition to the onsite exhibit, photos are shared in an online exhibit and Facebook group in hopes that some of these ‘Forgotten’ faces will remembered and named. Curator of Engagement & Dialogue Sinead Cox shares highlights of the exhibit’s remembering efforts so far.

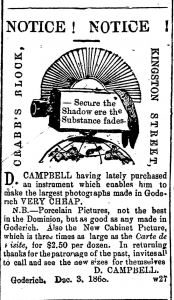

Semi-Weekly Signal, (Goderich) 07-27-1869 pg 2

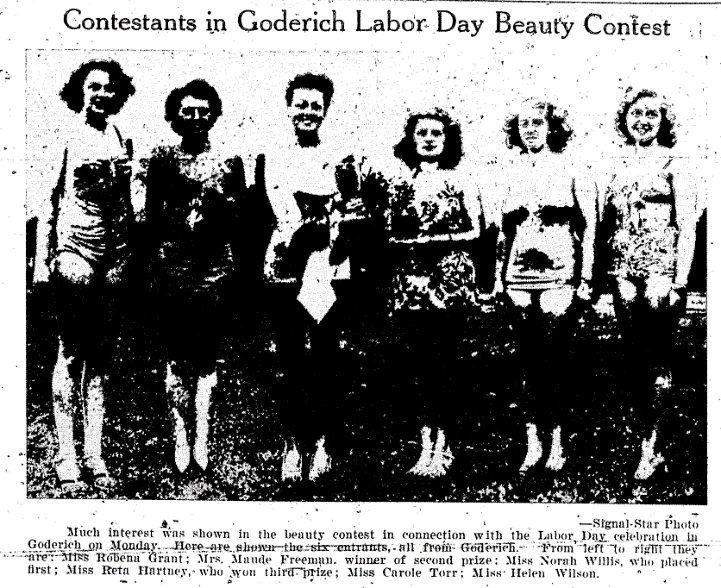

The Huron County Museum has an incredible collection of photographs in its Archives – especially studio portraits from commercial photographers within Huron County (spanning the county from Senior Studio in Exeter, Zurbrigg in Wingham, and everywhere in between). Not all of these photographs came with identifying information for their subjects, or even known donors or photographers. The Forgotten exhibit has provided an opportunity to delve deeper into the clues that can be present in everything from associated family trees to fashion styles, photographer’s marks, and photography methods that can provide more context, narrow timelines, or even lead to the re-discovery of names. I am especially grateful for the enthusiastic participation we have already had from photo detectives from the public who have contributed to remembering Huron County’s ‘Forgotten’ faces. Hopefully this is just the beginning of adding value to our collection.

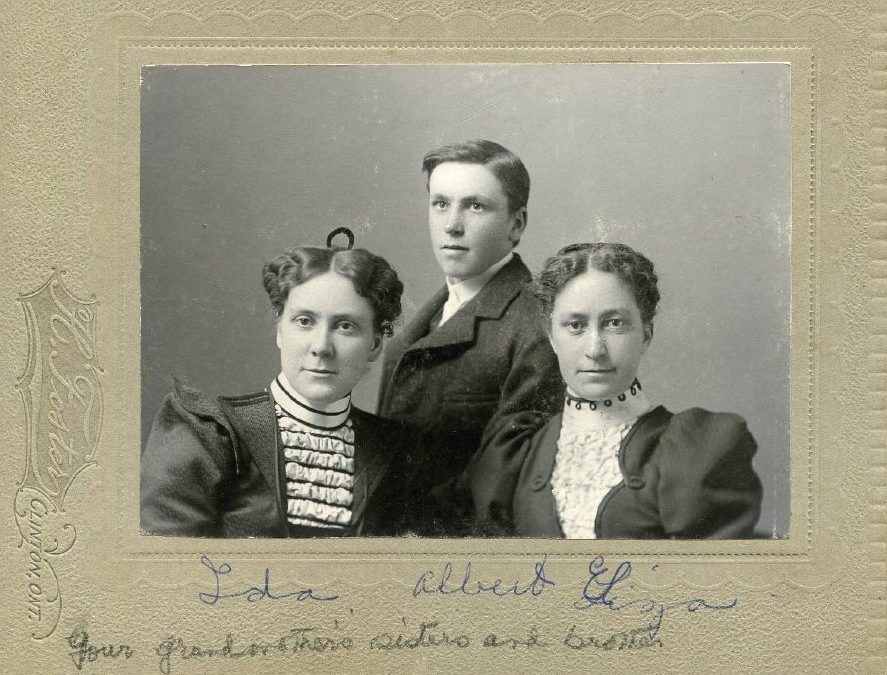

Professional studio photographs were often (and still are!) sent as gifts to family and friends. Local photographers saved negatives to sell reprints at a later date, and these negatives were also sometimes inherited when a studio changed hands. It’s very possible your own family photo collection contains the duplicate of a photo that exists in the possession of an archive or a distant relation somewhere else in the world. Finding matches between the faces in those photos is one way to solve photographic mysteries, and why a shared space to upload and comment on photos, like the Forgotten Facebook group, has the potential to put names to faces even after more than a century has passed since the camera flash!

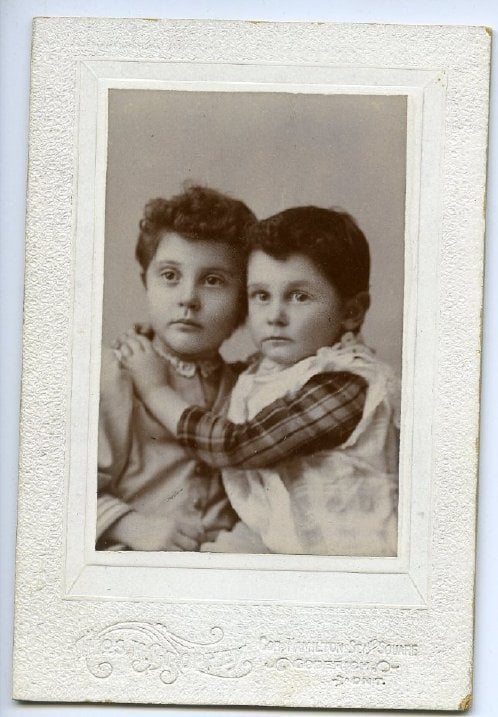

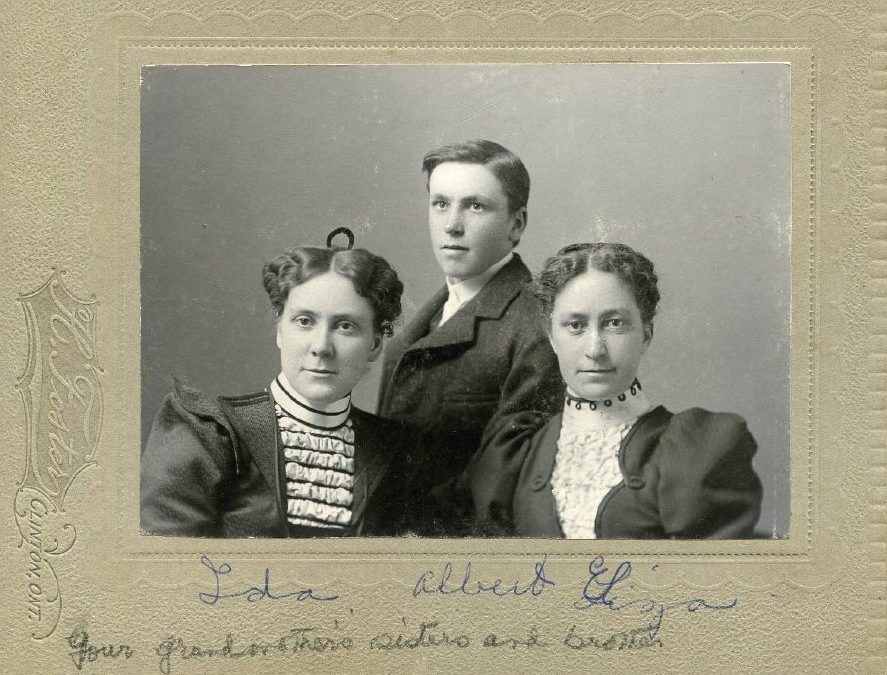

2011.0013.020. Photograph

2017.0013.011. Glass negative

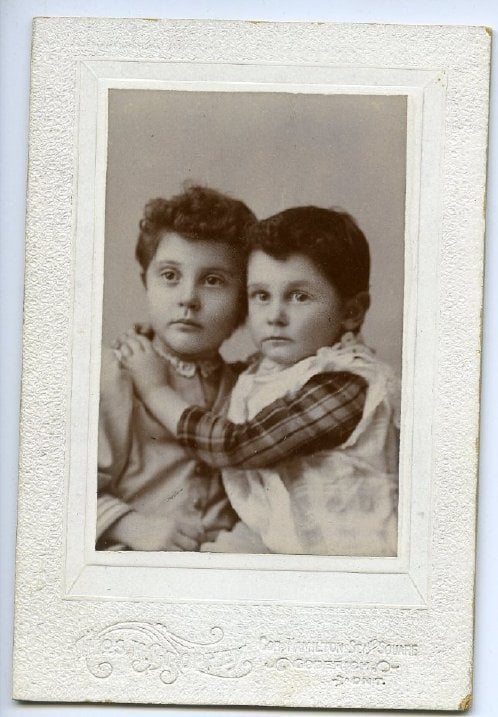

During preparation for the exhibit, staff recognized that a photograph and a glass negative from unrelated donations depicted the same image of a pair of children (their nervous expressions at having their photo taken were difficult to miss). The photo and negative came to the museum from different donors, six years apart. Information provided with the donation of the photograph indicates that these children may be related to the McCarthy and Hussey families of Ashfield Twp and Goderich area; the studio mark for Thos. H. Brophey is also visible on its cardboard mount, dating the image approximately between 1896 and 1904. The matching negative came from a collection related to Edward Norman Lewis, barrister, judge and MP from Goderich. The shared connection between the donations provides one more clue to help identify the unnamed children, and gives the negative meaning and value (through a place, time and potential family connection) it didn’t previously have without the photograph’s added context. You can see both the photograph and the negative on display in the temporary Forgotten exhibit, which is on at the Museum until fall 2022.

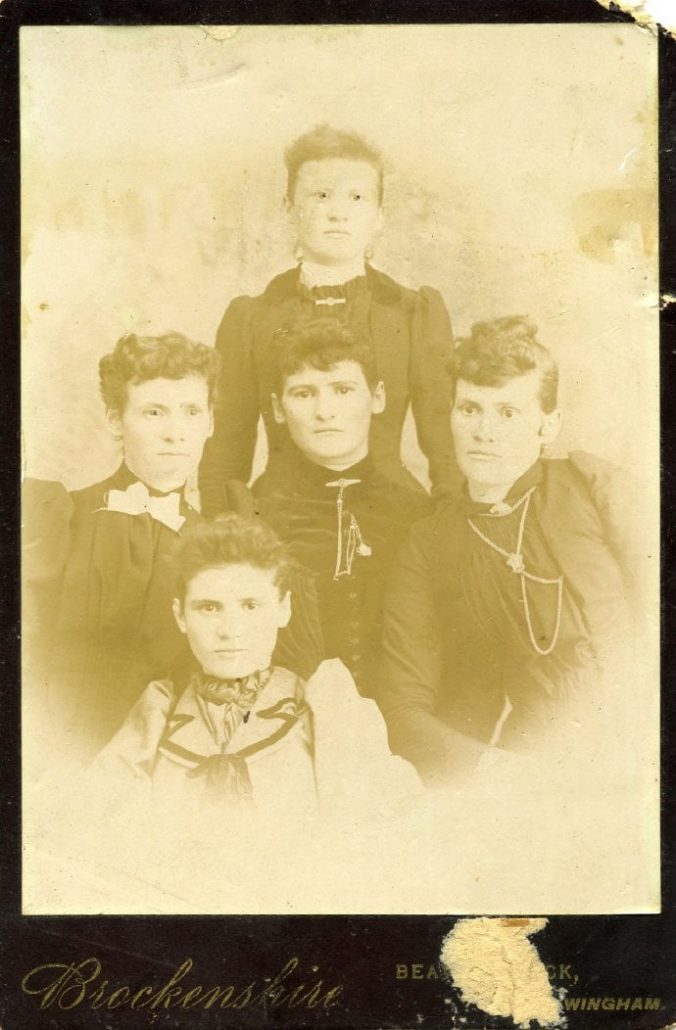

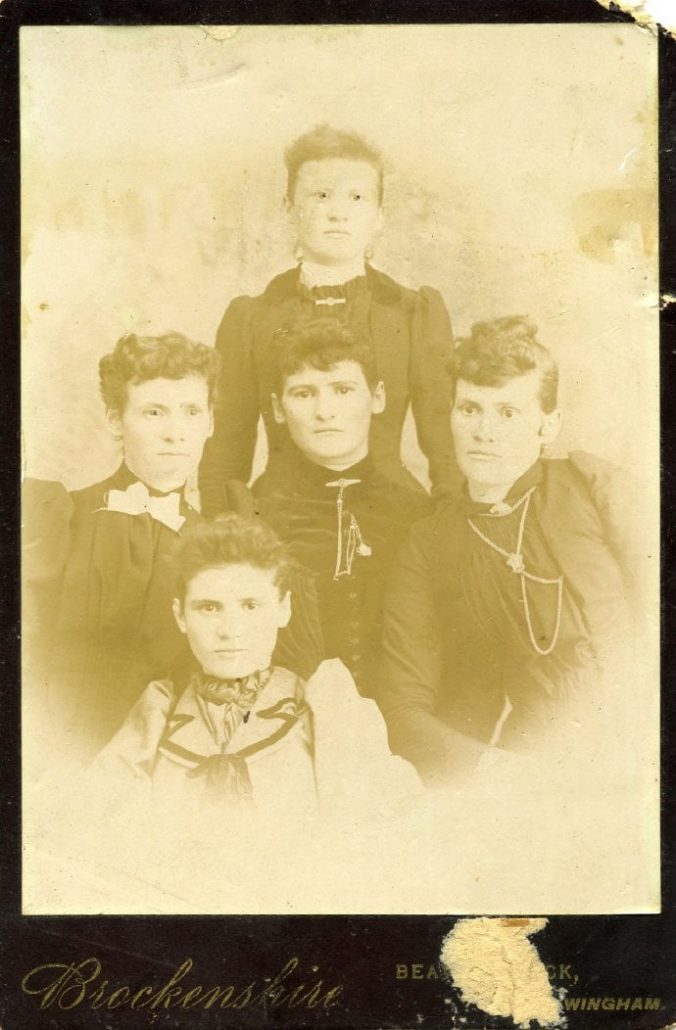

2021.0053.006. The “Garniss sisters”: Sarah Ann, Elizabeth, Eliza Maria Ida, Jemima, Mary Lillian. Can you help us identify which sister is which?

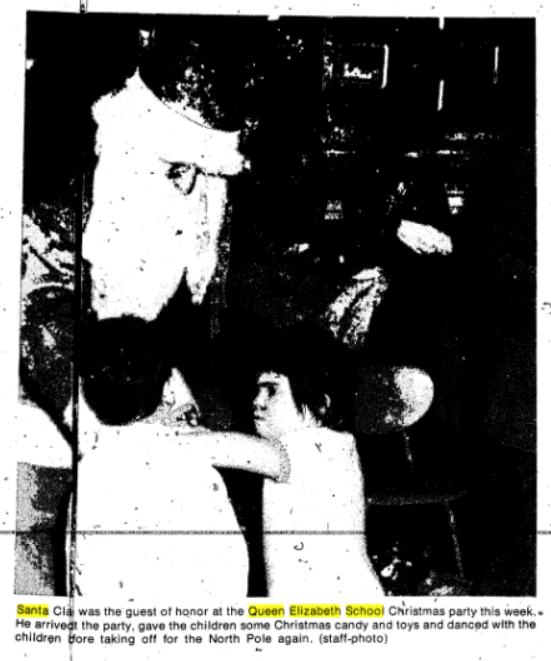

Sometimes photographs arrive to the collection with partial identifications or known connections to a certain family, even when individual names are missing. In those cases, knowledge of family histories can help pinpoint who’s who. Members of the Facebook group were recently able to name all five Morris Township women identified as only the “Garniss sisters” on the back of a photo from Brockenshire Studio, Wingham.

A996.001.095

Patterns tend to emerge with access to larger collections from the same location or time period. Although studio photographers later in the 19th century prided themselves on offering a large selection of backdrops, photos from local studios in the 1860s and 1870s often show a more simple set-up. In posting the ‘Forgotten’ photos online, I noticed that the studio space of Goderich photographer D. Campbell can be recognized by the consistent presence of a striped curtain in the background (and more often than not the same tassel-adorned chair) and a distinctive pattern on the floor, as seen in both the photos above and below. This helped identify additional photographs as Campbell’s work, and therefore place them in Goderich circa 1866-1870 , even when a photographer’s mark or name was absent from they physical photo.

A996.001.071. This photograph is labelled as “the Miss Henrys.” Do you have any information that might reveal their first names?

Crowdsourcing information through the online exhibit and group has allowed fresh pairs of eyes to notice detail previously missed in some of the museum’s photos, even when the evidence was captured by the staff doing the scanning and cataloguing work. In November, the Facebook group spotlighted unidentified soldiers, and one of the members pointed out a photographer’s mark embossed on the bottom right corner of a group photo. Staff were able to look at the original photo to get a clearer look to confirm the studio was identified as “G. West & Sons, Godalming.” Godalming is a town in Surrey, England near Witley Commons, which hosted many Canadian soldiers during the First and Second World Wars.

2004.0044.005. Photographer: G. West & Sons, Godalming, Surrey, U.K.

A950.1740.001

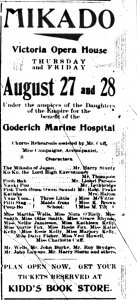

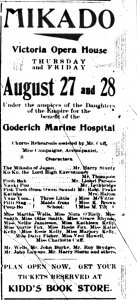

The Signal 08-27-1903 pg 8.

Comparing photographs with other readily available local historical resources like Huron’s digitized newspapers can also help provide new insight. Partial identifications on a group photo of young women in theatrical costumes without a location allowed a group member to link it to a 1903 Goderich production of Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Mikado. Further research in the newspapers provided a full list of the names of the participating cast and more information about the production, which toured Huron County. This information is now attached to the photograph’s catalogue record to benefit future researchers.

Although many historical photos may be ‘Forgotten’, if they are preserved and housed they are not lost. They still retain the potential for remembering , and to be re-connected to descendants and communities through extant clues and the growing possibilities of digitization and online sharing. For more highlights from the exhibit and tips for identifying mystery subjects photos or caring for your own collections, join is Feb. 9, 2022 for the second webinar in our exhibit series: Forgotten in the Archives.

If you can help identify a ‘Forgotten’ face, email us at museum@huroncounty.ca!

For more on the Forgotten: People & Portraits of the County exhibit and related coming events:

by Sinead Cox | May 15, 2020 | Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

In this two-part series, Curator of Engagement & Dialogue Sinead Cox illuminates how the Second World War entered the walls of the Huron Historic Gaol. Click here for Part One: The ‘Defence of Canada’ in Huron County.

In the summer of 1940, when the Netherlands fell to Nazi Germany, a ripple effect extending to the Great Lakes would unexpectedly commit thirteen “alien seamen” to the Huron Jail.*

At the outset of the Second World War in 1939, the Oranje Line, also known in Dutch as Maatschappij Zeetransport N.V, was a relatively new Dutch-owned transport company that serviced Great Lakes routes. The Line had only commenced operations in 1937, and its fifth vessel in the Great Lakes, the 2,800 ton diesel freighter Prins Willem III was the first deep sea motor ship to come inland; she embarked on her maiden voyage in September, 1939.

On May 9th, 1940 the Prins Willem III departed neutral Antwerp, Belgium on a routine commercial journey under Captain W. P. C. Helsdingen. In the course of one day, the ship’s professional routine would be abruptly shattered. The Prins Willem III was off the coast of Flushing when a German bomb hit the water about 200 yards from the ship and caused a huge explosion and towering pillar of water. Germany had invaded the Netherlands. Planes were flying high and out of sight, but the crew could hear the whining sound of bombs as they fell nearby. Targeted by a machine gun onslaught from Nazi fighter planes, the ship escaped via the English channel. After narrowly surviving with their lives and the boat intact to reach England, the Dutch crew would soon learn that the formerly neutral Netherlands had capitulated and their home country was now occupied by Nazi Germany.

The ship continued on its planned journey to North American waters, docking at Montreal, Duluth, Milwaukee and finally Chicago on June 25th , successfully delivering a cargo of seeds and twine. At Chicago, the crew awaited orders regarding their next destination. Meanwhile, members of the Dutch government, including Queen Wilhelmina, had fled to London, England. The government in exile required all Dutch merchant vessels abroad to now sail under the British Merchant marines, and to report to an allied port to join the war effort: which could include transporting provisions or armaments. Canada being the closest allied country, the Netherlands Shipping Commission ordered the Prins Willem III to return to Montreal and “then embark for some unnamed foreign port,” according to the Chicago Daily Tribune. 17 out of the 19 crew members refused the orders.

The crew’s actions seemed to defy easy categorization as conscientious objection or mutiny. Captain Helsdingen assured the Chicago press that the men were neither striking, mutinous, nor even refusing to do their assigned jobs aboard the ship, but the crew would not leave the neutral waters of the United States (which would not enter the war until after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December, 1941). After their ordeal at the mercy of German bombs and guns, reluctance to return to a war zone aboard a ship that was not armed, and would not be provided an armed convoy, is hardly surprising. The Tribune quoted the crew as telling the captain, “If we cannot have weapons, we would rather spend our time in a United States jail than on the ocean.” They also feared for their families in a Nazi-occupied country and whether there could be reprisals against them—extending to arrests and transportation to concentration camps—for helping the allied cause by transporting munitions. According to the captain, the crew of the Prins Willem III feared Germany more than England.

The crew’s ‘sitdown strike’ left Commonwealth, Dutch and American authorities with no easy solutions. The standstill left most of the crew trapped on the ship, with only Captain Helsdingen legally permitted to go ashore. The crewmembers had no immigration documents to legally enter the United States, and because of the ongoing occupation of the Netherlands, the U.S. would not have been easily able to deport the sailors: thus Immigration authorities and the Coast Guard kept a close watch on the ship. The Captain could not take on an American crew to move the ship because of U.S. neutrality, and thus the Prins Willem III remained anchored unmoving at Navy Pier.

American newspaper reports emphasize that, rather than any assumed violent mutiny, the crewmembers were largely friendly and cheerful in their refusal to budge. During their months of isolation on board, the crew busied themselves cleaning, stripping and painting the masts, booms and deck, oiling “everything in sight, from door handles to winches,” and polishing every “spot of brass on the boat to glisten.” The Tribune declared when it finally left Navy Pier the Prins Willem III would probably be “the best painted, best oiled and best polished ship that ever left this port.” By September the crew’s plight had gained the sympathies of Dutch Chicagoans, who organized a committee to deliver care packages to the crew from pleasure boats.

The Dutch government-in-exile, the Oranje Line and Canadian authorities finally devised a solution in October: the Prins Willem III would take on a Canadian crew recruited from Montreal. Ten private police from the Pinkerton Detective Agency in the United States were hired to come aboard the ship with the fourteen Canadian crew-members to prevent resistance or sabotage, and the ship was escorted by the U.S. Coast Guard during its departure from Chicago. There was ultimately no violence from the crew confined below deck; according to Time Magazine, “internment in Canada looked better to the bored, sequestered Dutch than gazing at the Chicago skyline all day.” Their initial stop according to the American reports was to be an “unannounced Canadian destination,” later specified as an “Ontario Port.” That port was Goderich.

Ships in Goderich harbour, date unknown Photographer: Reuben R. Sallows (1855 – 1937)

On October 16th, 1940 the Prins Willem III—presumably painted, oiled and polished to perfection—arrived in the Goderich harbour. The secrecy surrounding the chosen port for the uncooperative crew’s disembarkment meant local customs workers were completely surprised by the ship’s unscheduled arrival, and began a tentative dialogue with Captain Helsdingen regarding next steps while further instructions from Ottawa were awaited. Again, the original crewmembers of the Prins Willem III were stuck in limbo on board, and again they made the most of it: according to the Clinton News-Record they came on deck “under the watchful eye of two [Pinkerton] detectives…getting great enjoyment out of perch fishing from the stern of the ship while they whistled modern American airs.” A local crowd of curious onlookers gathered at the harbour to gawk at the ship from a distance, and a host of exaggerated rumors quickly travelled throughout the community, including that the crew were held in irons and guarded by machine gun-wielding “G-men.”

Three days later, thirteen crew members quietly disembarked from the ship during the night, escorted by the RCMP in batches of no more than two men at a time.** Police vehicles delivered these men to the Huron Jail. The remaining crew changed their minds and agreed to sail with Captain Helsdingen and the Canadians. The Prins Willem III had vanished from the Goderich harbour by the next morning, and the Pinkerton Detectives caught a train back to Chicago.

Cell in the Huron Historic Gaol.

The crew’s confines on land might have been somewhat tighter and less comfortable than their previous situation on board the Prins Willem III. Detailed inmate records are not accessible from the 1940s, but regardless of how many prisoners were already ‘guests of the county’ at the time, the arrival of thirteen ‘alien seamen’ would have left the Huron Jail, which has only twelve cells, over-capacity and somewhat crowded. The crew, who may not have all spoken fluent English, would have received daily food rations worth 13 ¼ cents per inmate and would only be able to take fresh air from inside the jail’s walled courtyards.

The thirteen Dutchmen remained in jail for three weeks, until removed under RCMP guard on the afternoon of Saturday, November 9th; they left Goderich by rail. Their destination upon leaving Huron County was once again a mystery to the media and the public, but widely assumed to be a Canadian internment camp, where POWs, Jewish refugees from Europe, and civilian ‘enemy aliens’ of differing loyalties could be forced to cohabitate.

Captain Helsdingen and the Prins Willem III continued on to Montreal to enter into the service of the allies as originally ordered by the Dutch government-in-exile so many months earlier. The temporary Canadian replacements would eventually be relieved by a Dutch crew, and the boat outfitted with anti-aircraft guns and machine guns, but the Captain was to face continued refusals of work from his crew throughout the war. Confirming the original crew’s fears, an aerial torpedo struck the Prins Willem III off the coast of Algiers in March, 1943; the ship later capsized and sank, resulting in eleven deaths. None of the original crew from the Chicago sojourn were amongst the lives lost.

The international incident caused by the Prins Willem III in the Great Lakes may be largely forgotten today, but the plight of its crew demonstrates that the North American homefront was not always as peaceful or untouched by the conflict in Europe as we might imagine. Overnight, the capitulation of the Netherlands had left the crew of the Prins Willem III in a precarious situation after enduring a surely traumatizing ordeal during the Nazi invasion on May 10th, 1940. Facing uncertainty in the custody of North American authorities, versus what they might have deemed as an almost certain death re-entering a war zone without adequate protections, they took action (or rather inaction) that stymied multiple governments and brought the repercussions of the Second World War to an ‘Ontario Port’ as apparently nondescript as ours.

*A note on spelling: Jail & gaol are alternative spellings of the same word, pronounced identically. Both spellings were used throughout the history of the Huron Historic Gaol fairly interchangeably. Although as a historic site the Huron Historic Gaol uses the ‘G’ spelling more common to the nineteenth century, for this article I have chosen to employ the ‘J’ spelling that appeared more consistently in the 1940s.

** Newspaper reports record 16 crew members jailed, but the Jailer’s Report to Council for 1940 recorded 13 “alien seamen,” and this is also the number given by Martine van der Wielen-de Goede, who reviewed crewmembers’ testimonies later in London (see sources below).

Special thanks to Alana Toulin & Christina Williamson for research assistance that made this blog post possible!

Further Reading

Internment in Canada via the Canadian Encyclopedia: https://thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/internment

Internment resources from Library and Archives Canada: https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/politics-government/Pages/thematic-guides-internment-camps.aspx

Secondary Sources

Gillham, Skip, “The Oranje Line,” Telescope, Volume XXX, No. 5. (Sept-Oct 1981), pg 116-117.

Malcolm, Ian M, Shipping Losses of the Second World War, (Brinscombe Port Stroud: The History Press, 2013).

van der Wielen-de Goede, Martine, “Varen of brommen Vier maanden verzet tegen de vaarplicht op de Prins Willem III, zomer 1940,” Tijdschrift voor Zeegeschiedenis, No. 1 (Jan. 2008) Via https://docplayer.nl/173449011-Ten-geleide-tijdschrift-voor-zeegeschiedenis.html

Sources: Articles

“At Sea: Open Lanes.” Time Magazine, October 21, 1940, pg 29.

“Canada Jails 16 Dutch Seamen After Mutiny.” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 11, 1940.

“Dutch Crew Jailed.” The Wingham Advance-Times, October 17, 1940.

“Dutch Sailors Removed.” Huron Expositor, November 15, 1940.

“Dutch Sailors to Jail.” Clinton News-Record, October 24, 1940.

“Dutch Freighter Arrives in Goderich.” Clinton News-Record, October 17, 1940.

“Escapes Bombing; Reaches Chicago: Unloads Seeds, Twine.” Chicago Daily Tribune, June 27, 1940.

“Explains Dutch Sailors’ ‘strike’: They Fear Nazis.” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 28, 1940.

“Members of Crew Interned.” The Seaforth News, October 17, 1940.

“Sitdown Strike Strands Dutch Ship in Chicago.” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 26, 1940.

“Stranded Dutch Ship Sails with Canadian Crew: Idle Force Lets Sailors Aboard Quietly.” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 8, 1940.

“Strikers Mark Time.” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 27, 1940.

Wilson, Edward. “Aye, There’s Rub to Life Aboard Dutch Freighter: Crew Keeps Busy Polishing and Painting Ship.” Chicago Daily Tribune, September 7, 1940.

by Sinead Cox | May 7, 2020 | Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

In this two-part series, Curator of Engagement & Dialogue Sinead Cox illuminates how the Second World War impacted Huron County in unexpected ways at home, and even entered the walls of the Huron Historic Gaol. Click for Part Two, and the strange tale of how Dutch sailors became wartime prisoners in Huron’s jail.

During the Second World War, Canada revived the War Measures Act: a statute from the First World War that granted the federal government extended authority, including controlling and eliminating perceived homegrown threats. The Defence of Canada Regulations implemented on September 3, 1939 increased censorship; banned particular cultural, political and religious groups outright; gave extended detainment powers to the Ministry of Justice and limited free expression. In Huron County, far from any overseas battlefields, these changes to law and order would bring the Second World War closer to home.

Regulations required Italian and German-born Canadians naturalized as citizens after 1929 (expanded to 1922 the following year) to formally register as ‘enemy aliens’ and report once a month. In Huron County, jail Governor James B. Reynolds accepted the appointment of ‘Registrar of Enemy Aliens’ in the autumn of 1939, and the registration office was to operate from the jail in Goderich. There were also offices in Wingham, Seaforth and Exeter managed by the local chief constables of the police force.

Regulations required Italian and German-born Canadians naturalized as citizens after 1929 (expanded to 1922 the following year) to formally register as ‘enemy aliens’ and report once a month. In Huron County, jail Governor James B. Reynolds accepted the appointment of ‘Registrar of Enemy Aliens’ in the autumn of 1939, and the registration office was to operate from the jail in Goderich. There were also offices in Wingham, Seaforth and Exeter managed by the local chief constables of the police force.

In addition to its novel function as the alien registration office, the Huron Jail also housed any prisoners charged criminally under the temporary wartime laws. Inmate records from the time period of the Second World War cannot be accessed, but Reynolds’ annual reports submitted to Huron County Council indicate that one local prisoner was committed to jail under the ‘Defence of Canada Act’ in 1939, and there were an additional four such inmates in 1940. The most common charges landing inmates behind bars during those years were still typical for the county: thefts, traffic violations, vagrancy and violations of the Liquor Control Act (Huron County being a ‘dry’ county).

Frank Edward Eickemier, the lone individual jailed under the War Measures Act’s Defence of Canada regulations in 1939, was no ‘alien,’ but the Canadian-born son of a farm family in neighbouring Perth County. Nineteen-year-old Eickemier pled guilty to ‘seditious utterances’ spoken during the Seaforth Fall Fair, and received a fine of $200 and thirty days in jail (plus an additional six months if he defaulted on the fine). The same month the Defence of Canada regulations took effect, Eickemier had publicly proclaimed that Adolph Hitler’s Nazi Germany was undefeatable, and that if it were possible to travel to Europe he would join the German military. He fled the scene when constables arrived, but was soon pursued and arrested for “statements likely to cause disaffection to His Majesty [King George VI] or interfere with the success of His Majesty’s forces.” His crime was not necessarily his political views, but his disloyalty. The prosecuting Crown Attorney conceded, “A man in this country is entitled to his own opinion, but when a country is at war you can’t go around making statements like that.”

Bruce County law enforcement prosecuted a similar case in July of 1940 against Martin Duckhorn, a Mildmay-area farm worker employed in Howick Township, and alleged Nazi sympathizer. Duckhorn had been born in Germany, and as an ‘enemy alien’ his rights were essentially suspended under the War Measures Act, and he thus received an even harsher punishment than Eickemier: to be “detained in an Ontario internment camp for the duration of the war.”

Huron County Courthouse & Courthouse Square, Goderich c1941. A991.0051.005

In July of 1940, the Canadian wartime restrictions extended to making membership in the Jehovah’s Witnesses illegal. The inmates recorded as jailed under the ‘Defence of Canada Act’ in Huron that year were likely all observers of that faith, which holds a refusal to bear arms as one its tenets, as well as discouraging patriotic behaviours. That summer, two Jehovah’s Witnesses arrested at Bluevale and brought to jail at Goderich ultimately received fines of $10 or 13 days in jail for having church publications in their possession. Four others accused of visiting Goderich Township homes to discourage the occupants from taking “any side in the war” had their charges dismissed—due to a lack of witnesses. In 1943, the RCMP and provincial police collaborated to arrest another three Jehovah’s Witnesses in Goderich Township for refusing to submit to medical examinations or report their current addresses (therefore avoiding possible conscription); the courts sentenced the three charged to twenty-one days in the jail, afterwards to be escorted by police to “the nearest mobilization centre.”

By August of 1940, an item in the Exeter Times-Advocate claimed that RCMP officers were present in the area to ‘look up’ those individuals who had failed to comply with the law and promptly register as enemy aliens. A few weeks later, the first Huron County resident fined for his failure to register appeared in Police Court. The ‘enemy alien’ was Charles Keller, a 72-year-old Hay Township farmer who had lived in Canada for 58 years, emigrating from Germany as a teenager in 1882. According to his 1949 obituary in the Zurich Herald, Keller was the father of nine surviving children, a member of the local Lutheran church, and had retired to Dashwood around 1929. His punishment for neglecting to register was not jail time, but the fine of $10 and costs (about $172.00 today according to the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator).

Although incidences of prosecution under the ‘Defense of Canada Act’ in Huron County were few, the increased scrutiny and restrictions would have been felt in the wider community, especially for those minority groups and conscientious objectors directly impacted. Huron had a notable number of families with German origins, especially in areas like Hay Township where you can still see the tombstones of many early settlers written in German. The Judge who sentenced Frank Edward Eickemier for his public support of the Nazi regime in 1939 made a point of accusing him of casting a ‘slur’ on his ‘people’ and all German Canadians: the actions of the individual conflated with a much larger and diverse German community by a representative of the law. His case indicates that pro-fascist and pro-Nazi sentiment certainly did exist close to home, but a person’s place of birth or their religion was not the crucial evidence that could define who was or was not an ‘enemy.’

Next Week: Click for Part Two, and the strange tale of how stranded Dutch sailors ended up prisoners in the Huron County Jail during the Second World War.

*A note on spelling: Jail & gaol are alternative spellings of the same word, pronounced identically. Both spellings were used throughout the history of the Huron Historic Gaol fairly interchangeably. Although as a historic site the Huron Historic Gaol uses the ‘G’ spelling more common to the nineteenth century, for this article I have chosen to employ the ‘J’ spelling that appeared more consistently in the 1940s.

Further Reading

The War Measures Act via the Canadian Encyclopedia

Sources

Research for this blog post was conducted largely via Huron’s digitized historical newspapers.

“Faces Trial on Charge of Making Disloyal Remark.” Seaforth News, September 28, 1939.

“German Sympathizer Interned.” The Wingham-Advance Times, July 25, 1940.

“In Police Court.” Seaforth News, August 29, 1940.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Charged.” Zurich Herald, October 21, 1943.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Fined at Goderich.” The Wingham-Advance Times, August 22, 1940.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Refused Bail.” The Wingham Advance-Times, July 18, 1940.

“Looking Up Aliens Who Failed to Register.” The Exeter Times-Advocate, August 1, 1940.

“Police Arrest ‘Jehovah’s Witnesses.’” Seaforth News, June 27, 1940.

“Statement He Would Fight for Hitler Proves Costly.” The Wingham-Advance Times, October 5, 1939.

“To Register German Aliens.” The Seaforth News, October 12, 1939.

“Twenty-One Days.” The Lucknow Sentinel, October 28, 1943.

“Would Fight for Hitler-Arrested.” The Wingham Advance-Times, September 28, 1939.