by Sinead Cox | May 7, 2020 | Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

In this two-part series, Curator of Engagement & Dialogue Sinead Cox illuminates how the Second World War impacted Huron County in unexpected ways at home, and even entered the walls of the Huron Historic Gaol. Click for Part Two, and the strange tale of how Dutch sailors became wartime prisoners in Huron’s jail.

During the Second World War, Canada revived the War Measures Act: a statute from the First World War that granted the federal government extended authority, including controlling and eliminating perceived homegrown threats. The Defence of Canada Regulations implemented on September 3, 1939 increased censorship; banned particular cultural, political and religious groups outright; gave extended detainment powers to the Ministry of Justice and limited free expression. In Huron County, far from any overseas battlefields, these changes to law and order would bring the Second World War closer to home.

Regulations required Italian and German-born Canadians naturalized as citizens after 1929 (expanded to 1922 the following year) to formally register as ‘enemy aliens’ and report once a month. In Huron County, jail Governor James B. Reynolds accepted the appointment of ‘Registrar of Enemy Aliens’ in the autumn of 1939, and the registration office was to operate from the jail in Goderich. There were also offices in Wingham, Seaforth and Exeter managed by the local chief constables of the police force.

Regulations required Italian and German-born Canadians naturalized as citizens after 1929 (expanded to 1922 the following year) to formally register as ‘enemy aliens’ and report once a month. In Huron County, jail Governor James B. Reynolds accepted the appointment of ‘Registrar of Enemy Aliens’ in the autumn of 1939, and the registration office was to operate from the jail in Goderich. There were also offices in Wingham, Seaforth and Exeter managed by the local chief constables of the police force.

In addition to its novel function as the alien registration office, the Huron Jail also housed any prisoners charged criminally under the temporary wartime laws. Inmate records from the time period of the Second World War cannot be accessed, but Reynolds’ annual reports submitted to Huron County Council indicate that one local prisoner was committed to jail under the ‘Defence of Canada Act’ in 1939, and there were an additional four such inmates in 1940. The most common charges landing inmates behind bars during those years were still typical for the county: thefts, traffic violations, vagrancy and violations of the Liquor Control Act (Huron County being a ‘dry’ county).

Frank Edward Eickemier, the lone individual jailed under the War Measures Act’s Defence of Canada regulations in 1939, was no ‘alien,’ but the Canadian-born son of a farm family in neighbouring Perth County. Nineteen-year-old Eickemier pled guilty to ‘seditious utterances’ spoken during the Seaforth Fall Fair, and received a fine of $200 and thirty days in jail (plus an additional six months if he defaulted on the fine). The same month the Defence of Canada regulations took effect, Eickemier had publicly proclaimed that Adolph Hitler’s Nazi Germany was undefeatable, and that if it were possible to travel to Europe he would join the German military. He fled the scene when constables arrived, but was soon pursued and arrested for “statements likely to cause disaffection to His Majesty [King George VI] or interfere with the success of His Majesty’s forces.” His crime was not necessarily his political views, but his disloyalty. The prosecuting Crown Attorney conceded, “A man in this country is entitled to his own opinion, but when a country is at war you can’t go around making statements like that.”

Bruce County law enforcement prosecuted a similar case in July of 1940 against Martin Duckhorn, a Mildmay-area farm worker employed in Howick Township, and alleged Nazi sympathizer. Duckhorn had been born in Germany, and as an ‘enemy alien’ his rights were essentially suspended under the War Measures Act, and he thus received an even harsher punishment than Eickemier: to be “detained in an Ontario internment camp for the duration of the war.”

Huron County Courthouse & Courthouse Square, Goderich c1941. A991.0051.005

In July of 1940, the Canadian wartime restrictions extended to making membership in the Jehovah’s Witnesses illegal. The inmates recorded as jailed under the ‘Defence of Canada Act’ in Huron that year were likely all observers of that faith, which holds a refusal to bear arms as one its tenets, as well as discouraging patriotic behaviours. That summer, two Jehovah’s Witnesses arrested at Bluevale and brought to jail at Goderich ultimately received fines of $10 or 13 days in jail for having church publications in their possession. Four others accused of visiting Goderich Township homes to discourage the occupants from taking “any side in the war” had their charges dismissed—due to a lack of witnesses. In 1943, the RCMP and provincial police collaborated to arrest another three Jehovah’s Witnesses in Goderich Township for refusing to submit to medical examinations or report their current addresses (therefore avoiding possible conscription); the courts sentenced the three charged to twenty-one days in the jail, afterwards to be escorted by police to “the nearest mobilization centre.”

By August of 1940, an item in the Exeter Times-Advocate claimed that RCMP officers were present in the area to ‘look up’ those individuals who had failed to comply with the law and promptly register as enemy aliens. A few weeks later, the first Huron County resident fined for his failure to register appeared in Police Court. The ‘enemy alien’ was Charles Keller, a 72-year-old Hay Township farmer who had lived in Canada for 58 years, emigrating from Germany as a teenager in 1882. According to his 1949 obituary in the Zurich Herald, Keller was the father of nine surviving children, a member of the local Lutheran church, and had retired to Dashwood around 1929. His punishment for neglecting to register was not jail time, but the fine of $10 and costs (about $172.00 today according to the Bank of Canada’s inflation calculator).

Although incidences of prosecution under the ‘Defense of Canada Act’ in Huron County were few, the increased scrutiny and restrictions would have been felt in the wider community, especially for those minority groups and conscientious objectors directly impacted. Huron had a notable number of families with German origins, especially in areas like Hay Township where you can still see the tombstones of many early settlers written in German. The Judge who sentenced Frank Edward Eickemier for his public support of the Nazi regime in 1939 made a point of accusing him of casting a ‘slur’ on his ‘people’ and all German Canadians: the actions of the individual conflated with a much larger and diverse German community by a representative of the law. His case indicates that pro-fascist and pro-Nazi sentiment certainly did exist close to home, but a person’s place of birth or their religion was not the crucial evidence that could define who was or was not an ‘enemy.’

Next Week: Click for Part Two, and the strange tale of how stranded Dutch sailors ended up prisoners in the Huron County Jail during the Second World War.

*A note on spelling: Jail & gaol are alternative spellings of the same word, pronounced identically. Both spellings were used throughout the history of the Huron Historic Gaol fairly interchangeably. Although as a historic site the Huron Historic Gaol uses the ‘G’ spelling more common to the nineteenth century, for this article I have chosen to employ the ‘J’ spelling that appeared more consistently in the 1940s.

Further Reading

The War Measures Act via the Canadian Encyclopedia

Sources

Research for this blog post was conducted largely via Huron’s digitized historical newspapers.

“Faces Trial on Charge of Making Disloyal Remark.” Seaforth News, September 28, 1939.

“German Sympathizer Interned.” The Wingham-Advance Times, July 25, 1940.

“In Police Court.” Seaforth News, August 29, 1940.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Charged.” Zurich Herald, October 21, 1943.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Fined at Goderich.” The Wingham-Advance Times, August 22, 1940.

“Jehovah’s Witnesses Refused Bail.” The Wingham Advance-Times, July 18, 1940.

“Looking Up Aliens Who Failed to Register.” The Exeter Times-Advocate, August 1, 1940.

“Police Arrest ‘Jehovah’s Witnesses.’” Seaforth News, June 27, 1940.

“Statement He Would Fight for Hitler Proves Costly.” The Wingham-Advance Times, October 5, 1939.

“To Register German Aliens.” The Seaforth News, October 12, 1939.

“Twenty-One Days.” The Lucknow Sentinel, October 28, 1943.

“Would Fight for Hitler-Arrested.” The Wingham Advance-Times, September 28, 1939.

by Sinead Cox | May 18, 2017 | Huron Historic Gaol, Investigating Huron County History

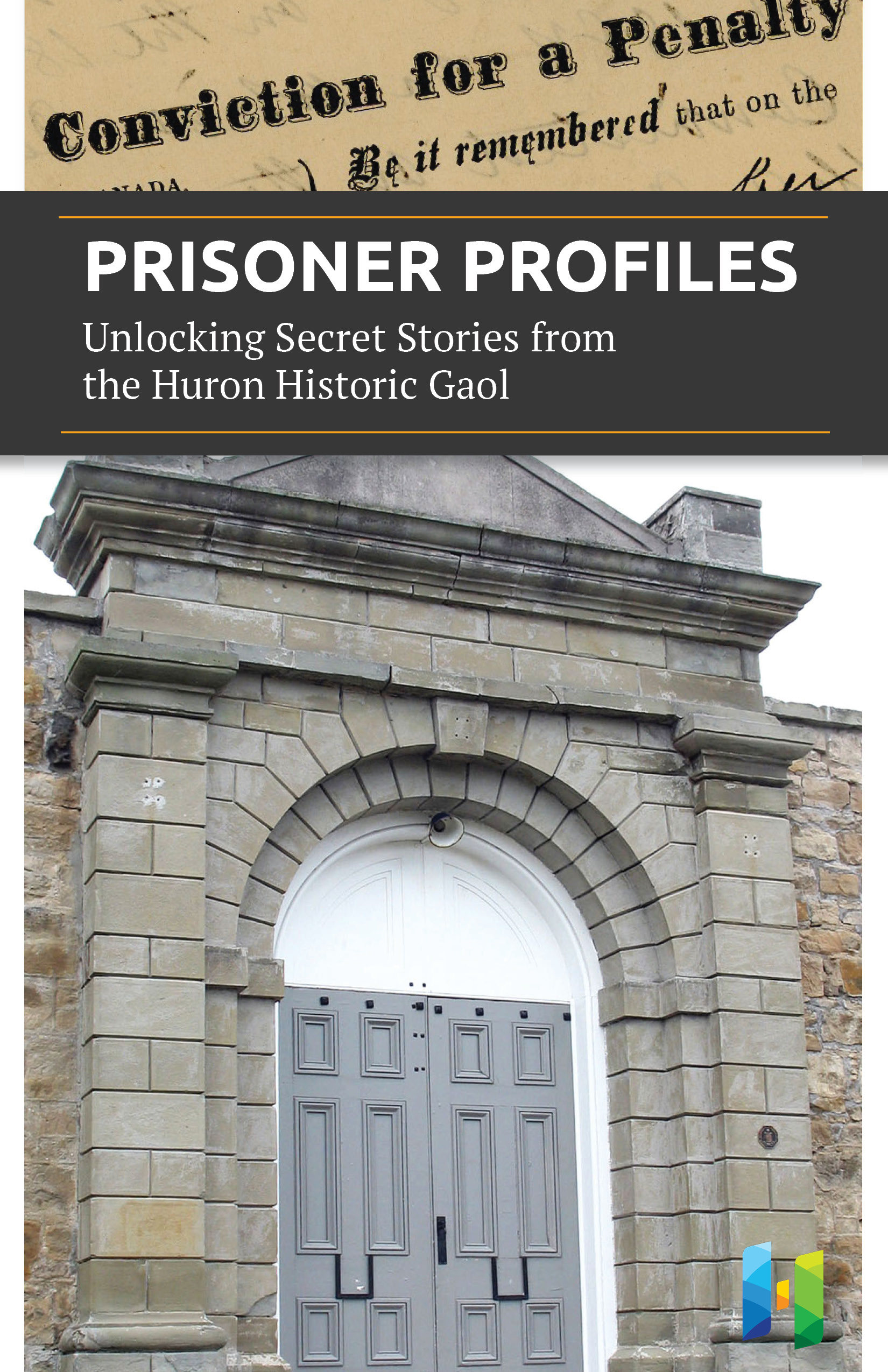

May 18th is International Museum Day! Museums and historic sites across the world are opening their doors for free today. For those whom cannot visit the Huron Historic Gaol in person, Student Museum Assistant Jacob Smith delves into the building’s past to reveal how some of Huron’s youngest prisoners ended up behind bars.

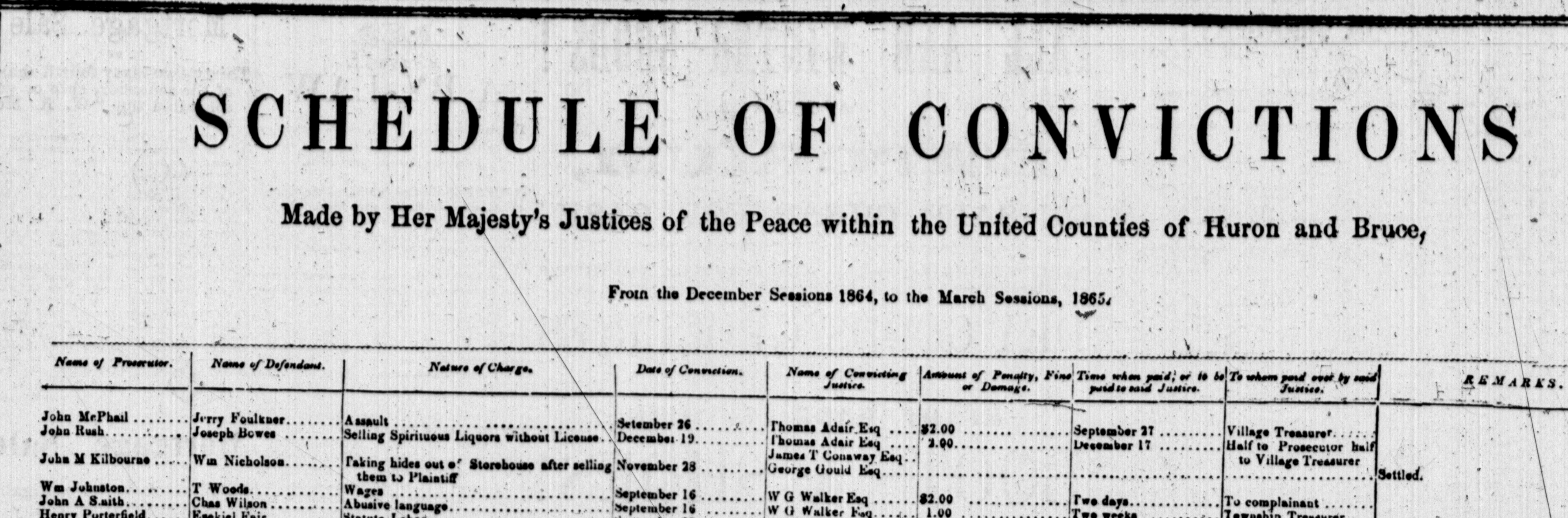

During its operation [1841-1972], hundreds of children were arrested and sent to the Huron Jail. Their crimes ranged from arson and theft to drunkenness and vagrancy. The most common crime that children committed was theft. In total, thefts made up over half of all youth charges between 1841 and 1911. In total, children under the age of 18 made up 7% of the gaol population during that time.*

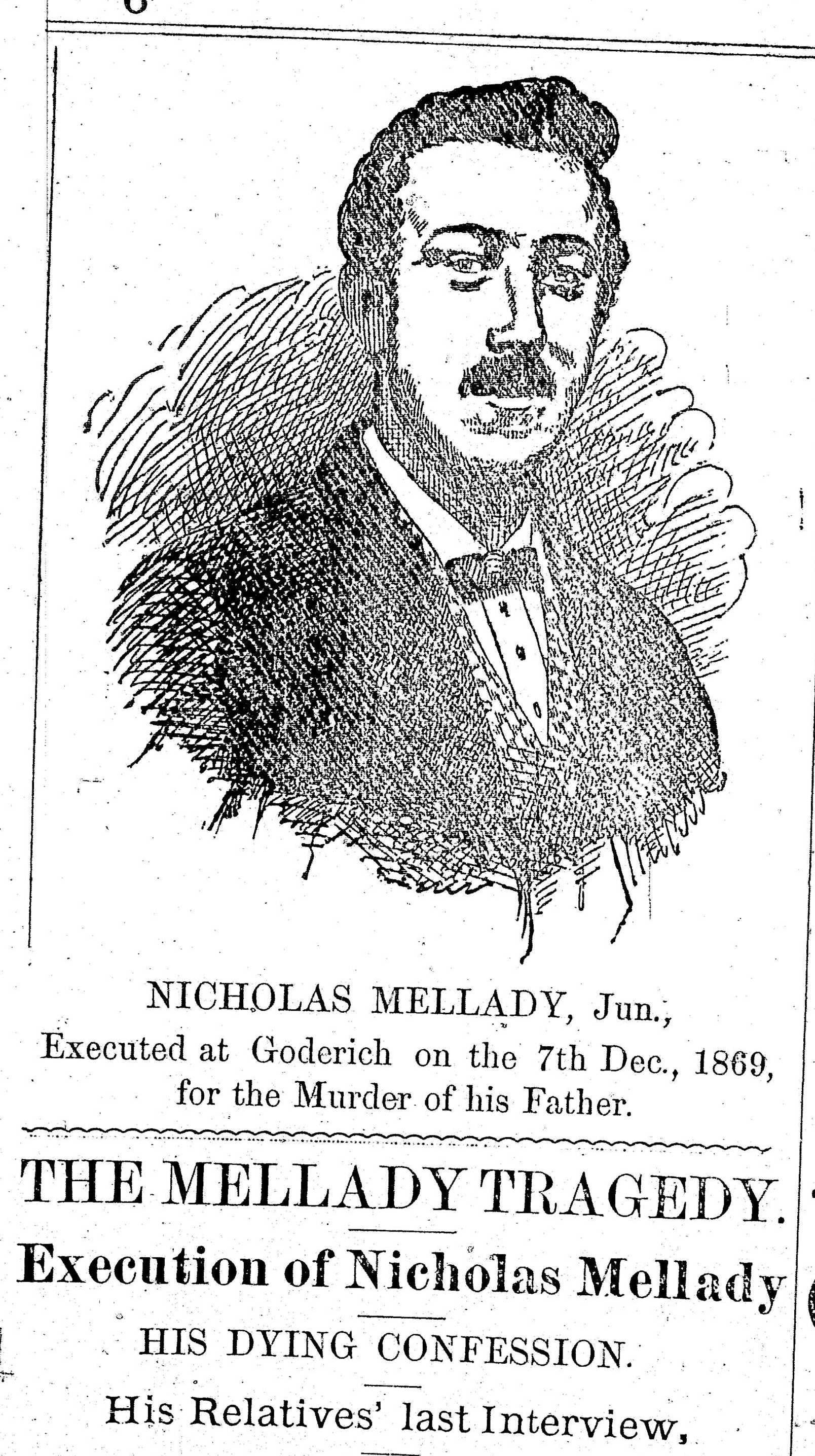

Occasionally, young people were sent to gaol for serious crimes. In 1870, William Mercer, age 17, was brought to the Huron Gaol and charged with murder. He was sentenced to die and was to be hanged on December 29, 1870. Thankfully for Mercer, his sentence was reduced to life in prison and was sent to a penitentiary. This is an example of an extreme crime for a young offender.

On many occasions, children were sent to gaol because they were petty thieves. Many young people who were committed for these types of crimes would only spend a few days in gaol. If the crime was more severe, children would be transferred from the gaol to a reformatory, usually for three to five years.

The youngest inmates that were charged with a crime were both seven years old. The first, Thomas McGinn, was charged in 1888 for larceny. He was discharged five days later and was sentenced to five years in a reformatory. The second, John Scott, was charged in 1900 for truancy; he was discharged the next day.

First floor cell block at the Huron Historic Gaol.

Unfortunately, some children were brought into gaol with their families because they were homeless or destitute. An example of this was in 1858, when Margaret Bird, age 8, Marion Bird, 6, and Jane Bird, 2, spent 25 days in gaol with a woman committed for ‘destitution’ (presumably their mother). Some children were also brought to the Huron Jail because their parents committed a crime and they had nowhere else to go while their parents were incarcerated. Samuel Worms, age 7, was sent to gaol with his parents because they were charged with fraud in 1865. He spent one day in the Gaol.

When reading through the Gaol’s registry, it is clear that times have certainly changed for young offenders. Most of the crimes committed by the young prisoners of the past would not receive as serious punishments today.

Here are some examples of their crimes in newspapers from around Huron County:

Richard Cain, 16, spent two days in jail.

The Huron Signal, 1896-09-17, pg 5.

Philip Butler, 15, spent eleven days in the Huron Jail.

The Exeter Advocate, 1901-08-29, pg 4.

Sources came from the Gaol’s 1841-1911 registry and Huron County’s digitized newspapers.

*Dates for which the gaol registry is available & transcribed. There were young people in the Huron jail throughout its history, into the twentieth century.

by Sinead Cox | Aug 25, 2015 | Huron Historic Gaol, Special Events

The Huron Historic Gaol’s popular evening Tuesday and Thursday tours, Behind the Bars, are coming to an end for another year! Your last chance to meet historic prisoners and staff from the gaol’s past is Thursday, August 27th at 7-9pm. In celebration of another successful season, Colleen Maguire, one of Behind the Bars’ veteran volunteer performers, gives readers a behind-the-scenes glimpse of what it takes to get into character and travel back to the gaol’s past every Tuesday and Thursday evening in July and August.

It is Thursday again and in a few short hours I will walk back into the 1890s. That’s because I portray Mrs. Margaret Dickson in the Behind the Bars tours at the Huron County Gaol, Goderich.

These Behind the Bars Tours feature about 18 actors who portray real people who lived, worked and were inmates of the Gaol, now a National Historic Site.

Mrs. Dickson became the Gaol Matron aka Governess when her husband William became the Gaoler in 1876. Together the couple raised five of their own children while living and working in the gaol. This is my third year portraying this beloved matron. I have researched countless hours to learn everything I can about her and her husband. At any given moment I must be able to answer any question posed to me by the public and be able to accurately answer their queries as if I were Mrs. Dickson. Do come for a Behind the Bars Tour and hear the rest of the remarkable story.

With the research aside how does someone physically prepare for their role in Behind the Bars?

It’s an hour and 15 minutes before the big doors of the Gaol will open to admit the curious so they can relive the history and the people of the Gaol where the 21st century literally collides with the 19th century.

[Physical] preparation for my role began months ago when I began growing my hair. The gaol is hot and [after] two [previous] seasons sweltering while wearing a wig it was time to try something different with my [short] hair. By growing it long enough I am able to pin an artificial matching hairpiece bun on the back. Now with a bit of practice, I can take my hair from a modern style to one befitting an older matron in the late 1800s. Mrs. Dickson was 67 years old in the year I portray her.

Before and After: Volunteer Colleen Maguire transforms into Mrs. Margaret Dickson, gaol matron.

The process begins by trading my t-shirt for a 100% cotton camisole. I learned early on to remove any over-the-head garments before starting the hair. Based on a photograph of Mrs. Dickson from this time period I know that she had white hair, parted in the middle and pulled to the back. My own hair is white, but naturally wavy, so getting the right look requires using some hair wax, twenty-one bobby pins and a lot of hairspray.

While the hairspray dries, it’s on to the next phase. Black stockings, then long pantaloons with a drawstring in front that have to be tied with a double knot, as they have been known to come undone resulting in a potentially embarrassing wardrobe malfunction. I then step carefully into my crinoline rather than take it over my head. The most common mistake that women reenactors make is not having the proper underclothing so that their dress or skirt can hang properly and fully. By now my hair should be fairly lacquered into place, so it’s time to attach and pin the bun hairpiece on and remove some hair pins now that the hairspray has taken over. A quick glance at the clock tells me that I have approximately 15 minutes left.

It’s a hot July day, so I grab my spray bottle and mist my cotton camisole with cool water, just enough to be wet through but not wet enough that my next item of clothing– my high collared, long, full sleeved Victorian working blouse–will become wet. I carefully guide and slip the floor-length long cotton twill skirt over my head. The Victorians were so smart, the closure on the back of my shirt allows me to button it at three different waist sizes. A little shake and my shirts fall into place. Next I clip my pewter Chatalaine to my skirt waistband; on its four long chains hangs two small keys- one for my writing desk and the other for Dr Shannon, the Gaol surgeon’s medicine cabinet, a pencil, small scissors and a quarter-sized timepiece. Pinning an antique cameo pin on the front of my high collar, placing a wedding band on my finger, and putting on my pince-nez eyeglasses, the final glance in the mirror indicates the transformation is complete. With my driver’s licence tucked into the lining of my antique purse, I set off for the car. Here is where history collides, for getting into a compact car with long skirts and lots of clothing is a bit tricky. You don’t want to be driving down the street with an article of clothing sticking out of your car door.

The matron’s keys: part of Colleen Maguire’s Behind the Bars costume.

Once at the Gaol I climb the spiral staircase to the second floor Gaoler’s Apartment just as Mrs. Dickson would have done countless times. This is where the Gaoler and his wife and all their children lived. Well, that and a smallish cottage built in one of the courtyards of the Gaol in 1862. What about the Governor’s House [a two-storey home attached to the gaol] you ask? Well that wasn’t built until 1901, long after Mrs. Dickson had passed on in 1895.

Mrs. Dickson was prolific letter writer, whether it be asking for a raise or writing letters asking for a House of Refuge to be built in Huron County. She was a social worker long before it was a fashionable career for women. Consequently, I have chosen to use as my props a small writing desk, ink well, and nib pen. Each night I slip my black cotton sleeve protectors on and begin the task of writing grocery lists, and other letters. Sometimes I surprise the [other] actors by reading to them a letter from their family that I have crafted or handing Dr. Shannon [the gaol surgeon] a note about an newly admitted inmate. It’s all part of the improv that takes place throughout the evening.

It’s 7 PM and the big Gaol doors have opened and in have flooded the tourists anxious to experience what life is really like in a 19th-century Gaol.

“Please allow me to introduce myself. I am Mrs. William Dickson, the Gaol Governess.”

Need to know more about what goes on behind the scenes at Behind the Bars? Check out coordinator Madelaine Higgins’ earlier post about planning the event.

Do you want to volunteer at the Huron County Museum or Huron Historic Gaol? To learn more about the Friends of the Huron County Museum, email museum@huroncounty.ca