by Sinead Cox | Jan 25, 2022 | Archives, Exhibits, Image highlights

The Huron County Museum’s temporary exhibit Forgotten: People and Portraits of the County features unidentified portraits captured by Huron County photographers. In addition to the onsite exhibit, photos are shared in an online exhibit and Facebook group in hopes that some of these ‘Forgotten’ faces will remembered and named. Curator of Engagement & Dialogue Sinead Cox shares highlights of the exhibit’s remembering efforts so far.

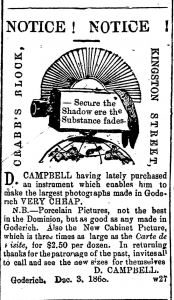

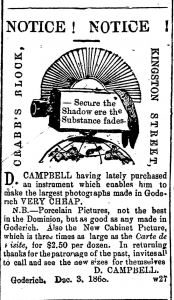

Semi-Weekly Signal, (Goderich) 07-27-1869 pg 2

The Huron County Museum has an incredible collection of photographs in its Archives – especially studio portraits from commercial photographers within Huron County (spanning the county from Senior Studio in Exeter, Zurbrigg in Wingham, and everywhere in between). Not all of these photographs came with identifying information for their subjects, or even known donors or photographers. The Forgotten exhibit has provided an opportunity to delve deeper into the clues that can be present in everything from associated family trees to fashion styles, photographer’s marks, and photography methods that can provide more context, narrow timelines, or even lead to the re-discovery of names. I am especially grateful for the enthusiastic participation we have already had from photo detectives from the public who have contributed to remembering Huron County’s ‘Forgotten’ faces. Hopefully this is just the beginning of adding value to our collection.

Professional studio photographs were often (and still are!) sent as gifts to family and friends. Local photographers saved negatives to sell reprints at a later date, and these negatives were also sometimes inherited when a studio changed hands. It’s very possible your own family photo collection contains the duplicate of a photo that exists in the possession of an archive or a distant relation somewhere else in the world. Finding matches between the faces in those photos is one way to solve photographic mysteries, and why a shared space to upload and comment on photos, like the Forgotten Facebook group, has the potential to put names to faces even after more than a century has passed since the camera flash!

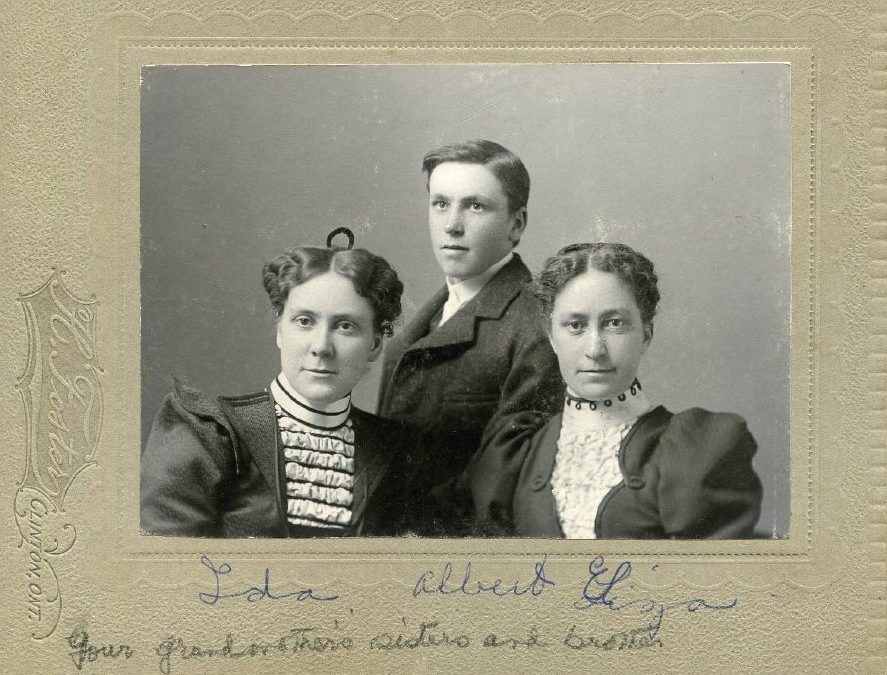

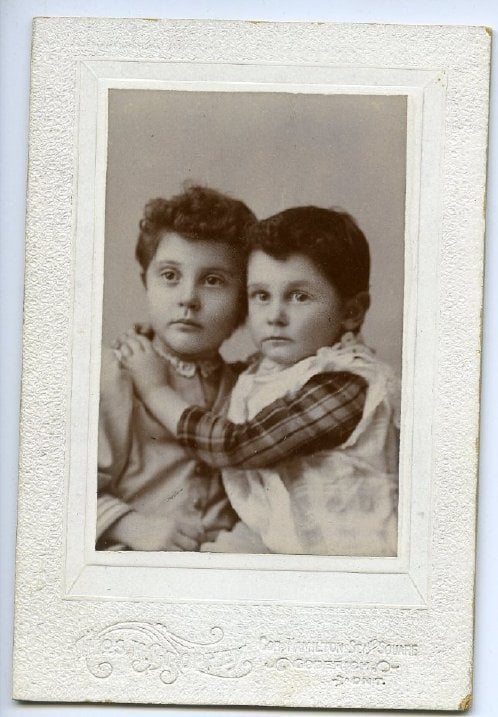

2011.0013.020. Photograph

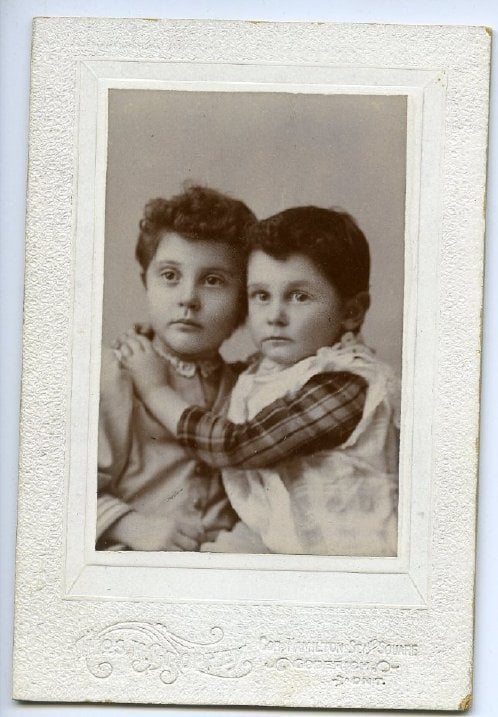

2017.0013.011. Glass negative

During preparation for the exhibit, staff recognized that a photograph and a glass negative from unrelated donations depicted the same image of a pair of children (their nervous expressions at having their photo taken were difficult to miss). The photo and negative came to the museum from different donors, six years apart. Information provided with the donation of the photograph indicates that these children may be related to the McCarthy and Hussey families of Ashfield Twp and Goderich area; the studio mark for Thos. H. Brophey is also visible on its cardboard mount, dating the image approximately between 1896 and 1904. The matching negative came from a collection related to Edward Norman Lewis, barrister, judge and MP from Goderich. The shared connection between the donations provides one more clue to help identify the unnamed children, and gives the negative meaning and value (through a place, time and potential family connection) it didn’t previously have without the photograph’s added context. You can see both the photograph and the negative on display in the temporary Forgotten exhibit, which is on at the Museum until fall 2022.

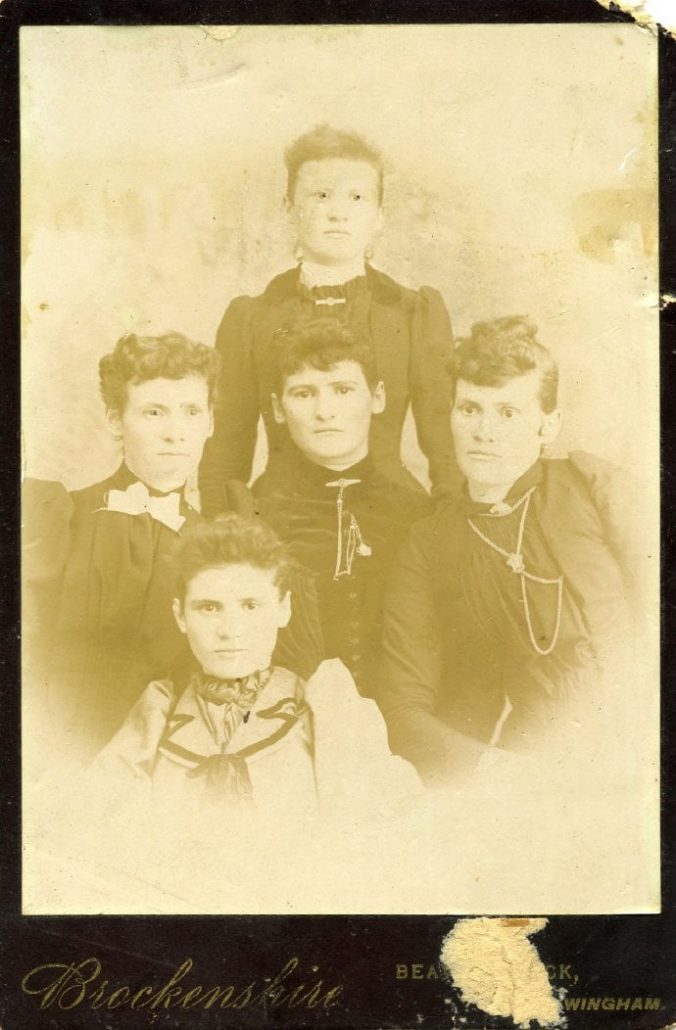

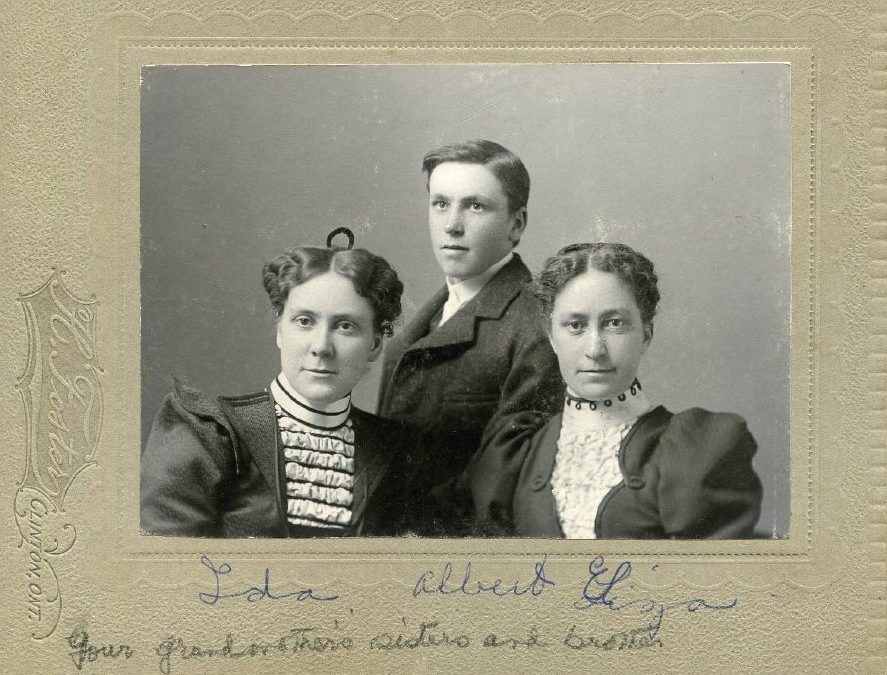

2021.0053.006. The “Garniss sisters”: Sarah Ann, Elizabeth, Eliza Maria Ida, Jemima, Mary Lillian. Can you help us identify which sister is which?

Sometimes photographs arrive to the collection with partial identifications or known connections to a certain family, even when individual names are missing. In those cases, knowledge of family histories can help pinpoint who’s who. Members of the Facebook group were recently able to name all five Morris Township women identified as only the “Garniss sisters” on the back of a photo from Brockenshire Studio, Wingham.

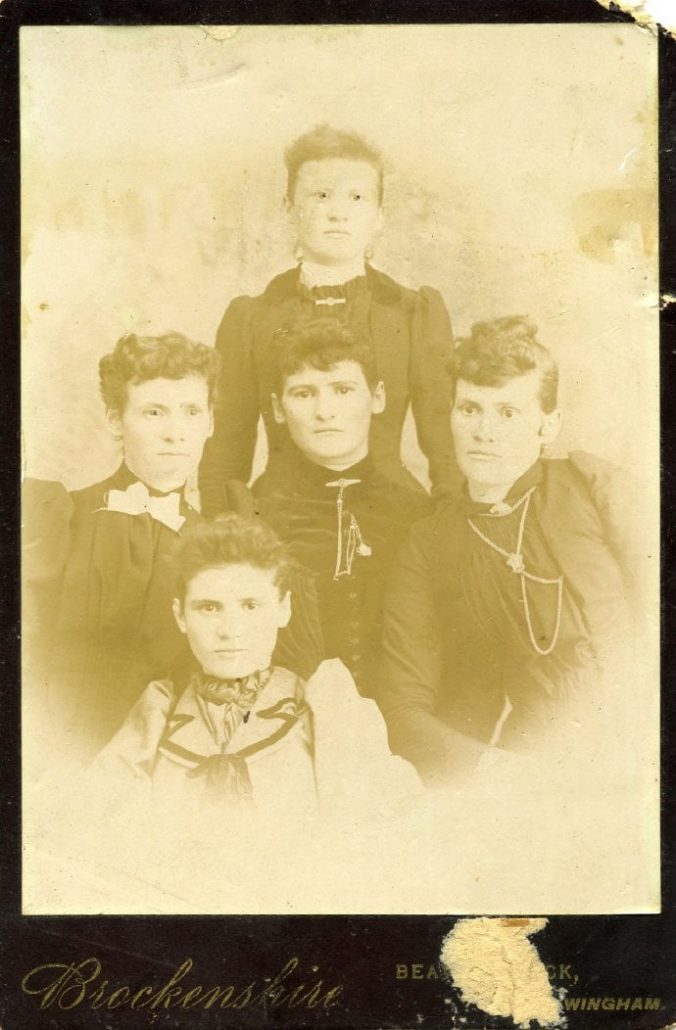

A996.001.095

Patterns tend to emerge with access to larger collections from the same location or time period. Although studio photographers later in the 19th century prided themselves on offering a large selection of backdrops, photos from local studios in the 1860s and 1870s often show a more simple set-up. In posting the ‘Forgotten’ photos online, I noticed that the studio space of Goderich photographer D. Campbell can be recognized by the consistent presence of a striped curtain in the background (and more often than not the same tassel-adorned chair) and a distinctive pattern on the floor, as seen in both the photos above and below. This helped identify additional photographs as Campbell’s work, and therefore place them in Goderich circa 1866-1870 , even when a photographer’s mark or name was absent from they physical photo.

A996.001.071. This photograph is labelled as “the Miss Henrys.” Do you have any information that might reveal their first names?

Crowdsourcing information through the online exhibit and group has allowed fresh pairs of eyes to notice detail previously missed in some of the museum’s photos, even when the evidence was captured by the staff doing the scanning and cataloguing work. In November, the Facebook group spotlighted unidentified soldiers, and one of the members pointed out a photographer’s mark embossed on the bottom right corner of a group photo. Staff were able to look at the original photo to get a clearer look to confirm the studio was identified as “G. West & Sons, Godalming.” Godalming is a town in Surrey, England near Witley Commons, which hosted many Canadian soldiers during the First and Second World Wars.

2004.0044.005. Photographer: G. West & Sons, Godalming, Surrey, U.K.

A950.1740.001

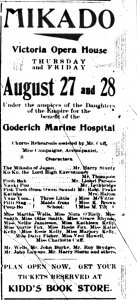

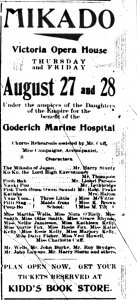

The Signal 08-27-1903 pg 8.

Comparing photographs with other readily available local historical resources like Huron’s digitized newspapers can also help provide new insight. Partial identifications on a group photo of young women in theatrical costumes without a location allowed a group member to link it to a 1903 Goderich production of Gilbert & Sullivan’s The Mikado. Further research in the newspapers provided a full list of the names of the participating cast and more information about the production, which toured Huron County. This information is now attached to the photograph’s catalogue record to benefit future researchers.

Although many historical photos may be ‘Forgotten’, if they are preserved and housed they are not lost. They still retain the potential for remembering , and to be re-connected to descendants and communities through extant clues and the growing possibilities of digitization and online sharing. For more highlights from the exhibit and tips for identifying mystery subjects photos or caring for your own collections, join is Feb. 9, 2022 for the second webinar in our exhibit series: Forgotten in the Archives.

If you can help identify a ‘Forgotten’ face, email us at museum@huroncounty.ca!

For more on the Forgotten: People & Portraits of the County exhibit and related coming events:

by Sinead Cox | Aug 25, 2020 | Archives, Blog, Exhibits, Image highlights, Investigating Huron County History

In anticipation of the Huron County Museum’s in-development exhibit Forgotten: People & Portraits of the County, volunteer Kevin den Dunnen takes an in-depth look at one of the many studio photographers to work in Huron County, and traces the professional and personal journey of Irene Burgess.

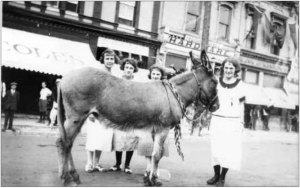

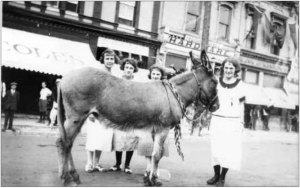

Summer of 1923 “old home week” in Mitchell, Ontario. Irene is the farthest left of the four. Image courtesy of the Stratford-Perth Archives.

Hiding within the Huron County Museum’s online and free-to-use newspaper archives are an unlimited number of stories like the one of Miss Irene Burgess. Irene Burgess was a woman that defied societal norms. In a time where women were rarely given the freedom to pursue a chosen career, Irene managed her own photography studio. While many women were expected to marry and have families, Irene stayed single. She was also faced with many tragedies in her life. Neither of her two siblings lived past 32. Her mother passed away at 51. Her niece nearly died at the age of 6. She lost the photography studio after an explosion. Through all of this, the communities of Perth and Huron Counties rose to support her.

Personal Life

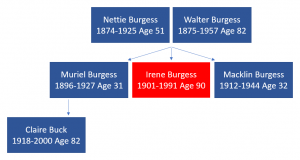

Nettie Irene Burgess was born September 20, 1901, in Mitchell, Ontario. Her parents were Nettie and Walter Burgess. She had two siblings – an older sister named Muriel, born in 1896, and a younger brother named Macklin, born in 1912. Her father, Walter, was a long-time photographer in Mitchell and owner of W.W. Burgess Studio. Growing up around photography gave Irene plenty of exposure to the business. This experience would prove to be important in her adult life.

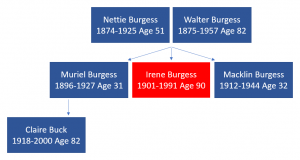

A brief family tree of the Burgess family. Of note, it only contains the names of family members included in this article.

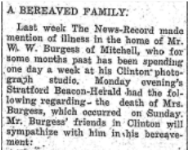

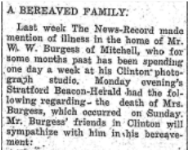

Excerpt from the November 26, 1925, edition of The Clinton News-Record detailing the passing of Irene’s mother Mrs. Nettie Burgess.

Irene experienced several tragedies throughout her life. By her 43rd birthday, only she and her father survived from their family of five. The first to pass was Irene’s mother, Nettie Helena Burgess, on November 22, 1925, at the age of 51. Irene’s sister, Mrs. D.F. Buck ( née Muriel Burgess) and her 6-year-old daughter Claire had been staying with her parents Walter and Nettie Burgess; Mrs. Buck had been ill for some time. During their stay, Claire became ill with pleuro-pneumonia. On the brink of death for several days, she began to recover with the help of her grandmother, Nettie. While caring for Claire, Nettie contracted pneumonia. Less than six days later, Nettie passed away in the presence of her family and nurse. 6-year-old Claire would live for another 75 years thanks to the care of her grandmother.

The next member of Irene’s family to pass would be her sister Muriel. Muriel was married to D.F. Buck, a photographer from Seaforth. They had three children, a daughter named Claire, and two sons named Craig and Keith. On March 24, 1926, an update in the Mitchell Advocate indicated that Irene would be visiting her sister, Mrs. D.F. Buck, at the Byron Sanitorium. According to the update, Mrs. Buck was “progressing favourably” but had been in poor health for some time. Almost fourteen months later on May 12, 1927, The Seaforth News wrote about the death of Mrs. D. F. Buck occurring the past Friday. While not mentioning the cause, the obituary described her as being “in poor health for a considerable period.”

On July 18, 1944, the Clinton News Record posted an obituary for Irene’s brother Macklin Burgess who passed away from a long-time illness at the age of 32. Macklin was in the photography and radio business. He left behind his wife, Elizabeth May, and three children, David, Nancy, and Dixie.

The next of Irene’s family to pass would be her father, Walter Burgess, in 1957 at the age of 82.

An interesting note in the life of Miss Irene Burgess is that she never married. In the Dominion Franchise Act List of Electors, 1935, Irene (age 34) is listed as a spinster (meaning a woman that is unmarried past the age considered typical for marriage). Whenever Irene is referenced in a newspaper, her title is Miss Irene Burgess. Irene would live until 1991.

The Clinton Studio

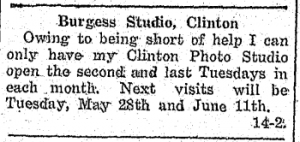

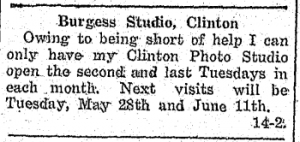

A notice posted by Walter Burgess in the May 23, 1929, edition of The Clinton News-Record

Walter Burgess operated a Clinton studio throughout the 1920s. The November 26th, 1925 edition of The Clinton News-Record mentions that Walter had only been spending one day a week at his Clinton Studio being “short of help.” A notice posted in The Clinton News-Record on May 23 1929 by Walter Burgess stated that his Clinton studio would only be open “the second and last Tuesdays in each month.” On October 1 of 1931, Walter announced that his newly-renovated Clinton studio would be open every weekday. His daughter, Miss Irene Burgess, would now be in charge of the location. Walter proclaimed Irene as “well experienced in Photography” and having “long experience with her father.” Not long after Irene became manager, Clinton residents would see the name Burgess Studios much more often in their newspapers.

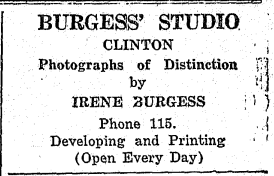

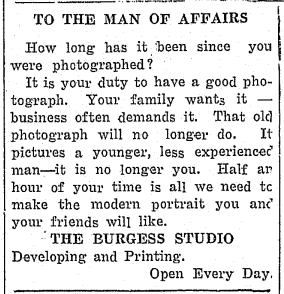

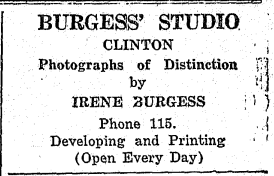

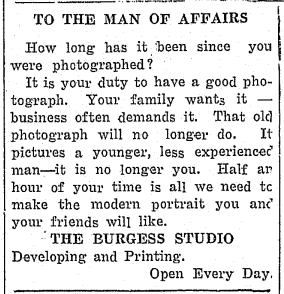

When Irene began managing the Clinton Studio in 1931, advertisements for the business began increasing. The slogan “Photographs of Distinction” appeared in advertisements from 1937 until the week of the fire. These ads were brief, only including the business name, slogan, Irene’s name, and the services provided. Earlier advertisements include one from 1933: “It is your duty to have a good photograph. Your family wants it – business often demands it.” Another example from 1932 reads, “You have plenty of leisure time to get that portrait of [the] family group taken.” The Clinton studio began under the leadership of Walter W. Burgess, but Irene would soon grow the business larger than her father had the time for– that is, until the explosion.

Advertisement posted in the January 26, 1933, edition of The Clinton News-Record.

The Explosion

On the afternoon of Monday, November 24, 1941, an explosion set fire to the second story of the J. E. Hovey Drug Store sweeping the entire business block. This was the place of business for Burgess Studio, Clinton. The fire swept through the building and damaged several businesses including R. H. Johnson Jewelry Store, Charles Lockwood Barber Shop, and Mrs. A MacDonald’s Millinery and Ladies Wear Shop. Irene was not in the studio when the fire started and did not call the authorities. Instead, the fire was discovered by Police Constable Elliot who identified smoke around the second-story window of the J. E. Hovey Drug Store Building. The fire was well covered in local newspapers. Featured on the second page of the Seaforth News more than a week after the incident, it was reported that the fire almost reached the “main business section of the town.” On its front page the week of the accident, The Clinton News-Record described the fire as “one of the most dangerous Clinton firemen have fought for years.” Unfortunately, Irene did not have insurance and was forced to close her business in Clinton. An update written on November 27, 1941 in The Clinton News-Record mentioned Irene’s departure for Mitchell to stay with her father for an “indefinite time.” A week later, on December 4, 1941, Irene posted a notice in the News-Record reading that, “owing to the recent fire damaging my equipment and Studio, I will be unable to continue operation.” She suggested that customers could mail their orders to the new studio. Additionally, customers could drive to her father’s studio in Mitchell and have their travel expenses paid. While this time must have been devastating for Irene, the community came together to show their support for her.

Community Support

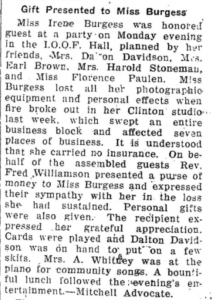

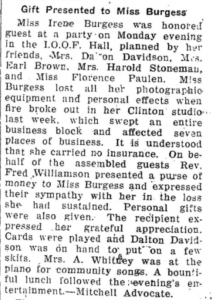

Excerpt from the December 12, 1941, edition of the Huron Expositor describing an even held in Irene Burgess’ honour.

Two weeks after the explosion, the Mitchell Advocate reported about an event held at the I.O.O.F. Hall where Irene was the “honoured guest.” The event was planned by Irene’s friends Mrs. Dalton Davidson, Mrs. Earl Brown, Mrs. Harold Stoneman, and Miss Florence Paulen. Entertainment included skits, piano music by Mrs. A. Whitney, cards, and a “bountiful lunch.” Irene received a “purse of money” and personal gifts from her friends along with their condolences. The rallying support for Irene shows the positive impact she had in the communities of Clinton, Seaforth, and Mitchell. An uplifting end to an otherwise sad story.

Conclusion

Aside from her brother’s passing in 1944, Miss Irene Burgess was seemingly never mentioned again in the Huron County Newspapers accessible through the digital newspaper portal. She would live until 1991 in St. Marys, Ontario.

Huron County’s digitized newspaper collection is a vast historical database where you can find historical stories from our own county. While performing research for the upcoming exhibit “Forgotten: People & Portraits of the County,” I came across this story which piqued my interest. Without access to the digitized newspaper collection, the story of Irene’s remarkable journey would never have been found. This post was compiled using newspaper articles between the years of 1925 and 1944. Birth and death dates were found within newspapers and using external resources.

If you have a photograph by a Huron County photographer you would like to donate or share, please contact the Museum’s archivist by calling 519-524-2686, ext. 2201 or email mmolnar@huroncounty.ca. To learn more about the Huron County Archives & Reading Room, visit: https://www.huroncountymuseum.ca/huron-county-archives/

A950.1857.001 A photograph taken by Burgess Studio Mitchell in 1914. If you have a photograph from Burgess’ Studio, Clinton you would like to donate, please consider contacting the Huron County Museum.

by Sinead Cox | Aug 17, 2017 | Artefacts, Collection highlights, Project progress

This week Summer student Shelby Hamp ends a six-week position as Artifact Photography Assistant at the Huron County Museum thanks to the Government of Ontario’s Summer Experience program. Shelby has been photographing museum artifacts in the Victorian Apartment gallery and main storage. In a guest post for our blog, Shelby shares some of her personal favourites among the artifacts she has taken pictures of.

The Huron County Museum is filled with many weird and incredible things. I have come across little critters in jars, intricate designs on silverware and plates, and the miniature collection.

My job at the museum is to photograph the toy collection, and this week I came across the miniatures. There is a ton of them; little Victorian furniture, coffins, washboards, and many other tiny versions of everyday things. Some were tiny product examples; others were children’s toys. These toys are in very good condition and are toys I wish I had grown up with. The neatest toys I have come across were small parlour items: a clock, couch, dinner gong, and a few other items. Everything is gold and the sofas and chairs have mauve fabric as cushioning. These toys were used between 1890 and 1910; the donor’s mother originally played with them and then the donor and her sister also played with them. Other doll items were also donated with this accession (gift to the museum) in 1995, and all have a history that dates to the late 1800s. The best part is: everything is still in mint condition.

Visit the Huron County Museum at 110 North Street, Goderich to see more of our collection! Do you have a favourite artefact? Share with us on Instagram or Twitter.

by Sinead Cox | May 2, 2017 | Artefacts, Collection highlights, Exhibits, Project progress, Uncategorized

Guest blogger and local Wingham artist Becca Marshall finishes her series on the museum as ‘gathering place’ with a behind the scenes look at her exhibit on display now at Brock University.

After a long year of photographing, developing, printing, and researching, we have finally made it to the finish line. As such, the end of my project was marked with a gallery exhibition of the photographs I took throughout the year accompanied by text and installation pieces on April 13th at the Marilynn I. Walker School of Fine and Performing Arts in St. Catharines, ON. I thought I would include some photos and descriptions of the pieces below for those who wish to see the end result, or, if you are in the area you can go to the gallery and see the installation in person (On display Tuesday-Saturday from 1-5 pm until May 5th).

A couple of photos from the installation process.

Over the course of a couple of days and with the assistance of Matthew Tegal and Marcie Bronson from Rodman Hall, and Professor Amy Friend and Lesley Bell from Brock University, we were able to set up and install the show.

Step Lightly (2017) Pigment print on luster paper and graphite This is the beginning piece of the exhibition. The photo features the train of Jean (Scott) Taylor’s wedding dress and is accompanied by personal writing in graphite directly on the wall next to the image so that it can only be seen up close. A smaller image is hidden to the side of the text of an old bottle of Potassium Chlorate medication.

Shelf Life (2017) Assortment of boxes This piece takes up the span of the long wall. The eclectic boxes are a stand in for the discovery process that a person experiences in the museum. Visitors are encouraged to take their time opening the boxes and looking for things that might have been left behind.

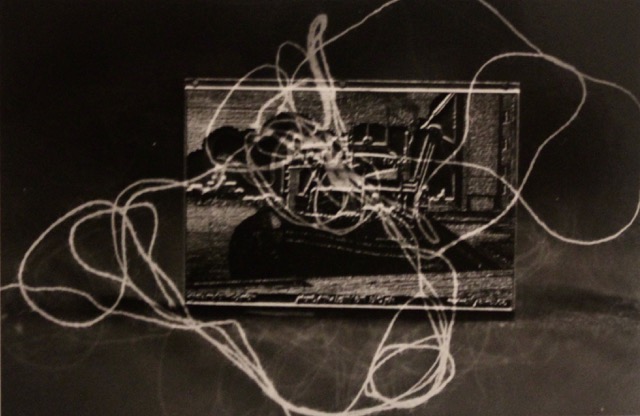

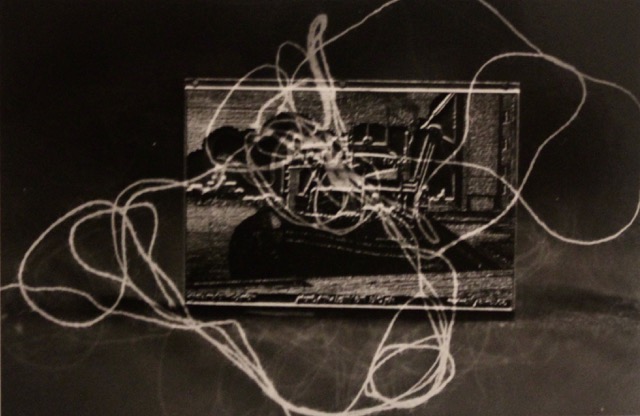

Pulling Threads (2017) Pigment print on luster paper, graphite, and archival tissue paper This piece consists of the large format print of the child’s sewing machine from the museum coupled with a collage of tissue paper with fragmented writing. Beneath these sheets are more hidden photos. The viewer either has to lift the pages up to view the smaller pieces, or they might catch a glimpse when someone walks by and the breeze lifts up the pages for a few moments, exposing the photos underneath.

Twelve Parts Fragile (2017) Pigment print on cotton rag paper The final piece of the show is a series of artifact photographs presented side by side so that they read like a sentence. This piece ties together the nature of the museum- the bringing together of like and unlike things to share their stories.

In many ways, I still cannot believe that this project is over. It was the experience of a lifetime and I am so grateful to the incredible staff at the museum who so generously gave their time and resources to help me better understand the nature of collections, curation, and our relationship to artifact display.

In many ways, I still cannot believe that this project is over. It was the experience of a lifetime and I am so grateful to the incredible staff at the museum who so generously gave their time and resources to help me better understand the nature of collections, curation, and our relationship to artifact display.

Additionally, without the support of my supervising instructors, Professor Amy

Friend and Dr. Keri Cronin, along with the advice and aid of Matthew Tegal, Marcie Bronson, and Lesley Bell, this project would never have gotten off the ground. Their constant support was of the utmost value. Overall, I learned so much about the silent conversations and nuances that inform our interactions with artifacts from the past – and I am so grateful for those of you who followed

me along on this journey.

by Sinead Cox | Jan 4, 2017 | Artefacts, Collection highlights, Investigating Huron County History, Project progress

Introducing a Brock University Student’s Project in Collaboration with the Huron County Museum & Archives, PART II

For those who missed the last post, my name is Becca Marshall – a fourth year student from Brock University where I am working on a school project with the assistance of the Huron County Museum and Archives. Basically, I am creating a series of analog photographs of museum artifacts along with a research paper as I study the theory of removed perception and constructed narratives in museums. If you want more background on my project, check out the original post that introduces my research! Today I want to update you on one of my favourite artifacts to research and photograph thus far – a linoleum block carved by Tom Pritchard.

At first I think I gravitated towards Pritchard’s linoleum blocks because my “art student” side was simply interested in seeing a piece of this artistic practice, as linoleum block printing is not something you encounter often nowadays. Not only does the museum have a collection of Pritchard’s linoleum blocks, but also a sketchbook and some of his art supplies. The most interesting part of this discovery process was going to find out more about Pritchard in the archives, only to discover that most of his folder was full of documents pertaining to his experience in the war. This incident prompted a line of inquiry in my research regarding human nature’s urge to essentially “fill in the blanks” in order to neatly label someone; many of us don’t like loose ends so we try to wrap our understandings of people into neat little boxes. For example, I had labelled Pritchard as solely an artist in my mind until I read his file – after that whenever I wrote research notes I found myself referring to him as a soldier. In fact, this label became so fixed in my head that when I was sorting through my photographs of

At first I think I gravitated towards Pritchard’s linoleum blocks because my “art student” side was simply interested in seeing a piece of this artistic practice, as linoleum block printing is not something you encounter often nowadays. Not only does the museum have a collection of Pritchard’s linoleum blocks, but also a sketchbook and some of his art supplies. The most interesting part of this discovery process was going to find out more about Pritchard in the archives, only to discover that most of his folder was full of documents pertaining to his experience in the war. This incident prompted a line of inquiry in my research regarding human nature’s urge to essentially “fill in the blanks” in order to neatly label someone; many of us don’t like loose ends so we try to wrap our understandings of people into neat little boxes. For example, I had labelled Pritchard as solely an artist in my mind until I read his file – after that whenever I wrote research notes I found myself referring to him as a soldier. In fact, this label became so fixed in my head that when I was sorting through my photographs of

artifacts and pairing them with their donors I mistakingly wrote Pritchard’s name next to a WWII gas mask instead of his linoleum block. As I reflected on this little mishap, I remember thinking of what a large role our minds play when looking at history – as we often take what we consider the most important aspects of someones life and define them by it.

The e xperience with Pritchard’s artifacts and archival file significantly directed my research as I have started looking at more museum studies articles and books on how curators negotiate incorporating narrative within exhibitions, and also the role that the public plays in their interpretations. I am finding it endlessly fascinating how key choices made by the curator can cue certain readings from the public, yet also how each visitor’s lived experience often redefines each interpretation. Luckily for me there is a significant amount of literature that touches on narrative theory in museums, as well as the opportunity to ask questions of the great staff at the Huron County Museum and Archives.

xperience with Pritchard’s artifacts and archival file significantly directed my research as I have started looking at more museum studies articles and books on how curators negotiate incorporating narrative within exhibitions, and also the role that the public plays in their interpretations. I am finding it endlessly fascinating how key choices made by the curator can cue certain readings from the public, yet also how each visitor’s lived experience often redefines each interpretation. Luckily for me there is a significant amount of literature that touches on narrative theory in museums, as well as the opportunity to ask questions of the great staff at the Huron County Museum and Archives.

I also thought I might take the time to answer a question I receive often in terms of the artistic component of this project – which is “Why analog photography?” To be honest its a question I ask myself repeatedly as well (usually after a long day in the darkroom when only one print turns out). I chose to work in an analog process for this project because I was hoping that my artistic practice would reflect my experience at the museum – essentially embodying the idea of “careful touch.” I’ve found that working and photographing the artifacts feels like a very reverent experience, so I want my artistic process to reflect this as I take the time to physically manipulate the photos in the darkroom. I also find that there are parallels between working with the artifacts and working with the prints in concerns to preservation and value. To me, an analog photograph has a certain amount of value due to the fact that there are normally limited prints (and even then each print might be a bit different from the last!) as well as a certain level of preciousness since each photograph takes such a long time to process and complete. Additionally, I have been getting to learn a bit more about preservation of artifacts from the Museum Technician, which has lead me to make connections to the steps taken to preserve an analog photograph – such as keeping it in the fixative chemical bath for the right length of time so that the light does not deteriorate the print, or the never ending quest to avoid dust. In this way, I find that the analog process simply connects my practice.

I also thought I might take the time to answer a question I receive often in terms of the artistic component of this project – which is “Why analog photography?” To be honest its a question I ask myself repeatedly as well (usually after a long day in the darkroom when only one print turns out). I chose to work in an analog process for this project because I was hoping that my artistic practice would reflect my experience at the museum – essentially embodying the idea of “careful touch.” I’ve found that working and photographing the artifacts feels like a very reverent experience, so I want my artistic process to reflect this as I take the time to physically manipulate the photos in the darkroom. I also find that there are parallels between working with the artifacts and working with the prints in concerns to preservation and value. To me, an analog photograph has a certain amount of value due to the fact that there are normally limited prints (and even then each print might be a bit different from the last!) as well as a certain level of preciousness since each photograph takes such a long time to process and complete. Additionally, I have been getting to learn a bit more about preservation of artifacts from the Museum Technician, which has lead me to make connections to the steps taken to preserve an analog photograph – such as keeping it in the fixative chemical bath for the right length of time so that the light does not deteriorate the print, or the never ending quest to avoid dust. In this way, I find that the analog process simply connects my practice.

Until next time,

– Becca Marshall

In many ways, I still cannot believe that this project is over. It was the experience of a lifetime and I am so grateful to the incredible staff at the museum who so generously gave their time and resources to help me better understand the nature of collections, curation, and our relationship to artifact display.

In many ways, I still cannot believe that this project is over. It was the experience of a lifetime and I am so grateful to the incredible staff at the museum who so generously gave their time and resources to help me better understand the nature of collections, curation, and our relationship to artifact display.

At first I think I gravitated towards Pritchard’s linoleum blocks because my “art student” side was simply interested in seeing a piece of this artistic practice, as linoleum block printing is not something you encounter often nowadays. Not only does the museum have a collection of Pritchard’s linoleum blocks, but also a sketchbook and some of his art supplies. The most interesting part of this discovery process was going to find out more about Pritchard in the archives, only to discover that most of his folder was full of documents pertaining to his experience in the war. This incident prompted a line of inquiry in my research regarding human nature’s urge to essentially “fill in the blanks” in order to neatly label someone; many of us don’t like loose ends so we try to wrap our understandings of people into neat little boxes. For example, I had labelled Pritchard as solely an artist in my mind until I read his file – after that whenever I wrote research notes I found myself referring to him as a soldier. In fact, this label became so fixed in my head that when I was sorting through my photographs of

At first I think I gravitated towards Pritchard’s linoleum blocks because my “art student” side was simply interested in seeing a piece of this artistic practice, as linoleum block printing is not something you encounter often nowadays. Not only does the museum have a collection of Pritchard’s linoleum blocks, but also a sketchbook and some of his art supplies. The most interesting part of this discovery process was going to find out more about Pritchard in the archives, only to discover that most of his folder was full of documents pertaining to his experience in the war. This incident prompted a line of inquiry in my research regarding human nature’s urge to essentially “fill in the blanks” in order to neatly label someone; many of us don’t like loose ends so we try to wrap our understandings of people into neat little boxes. For example, I had labelled Pritchard as solely an artist in my mind until I read his file – after that whenever I wrote research notes I found myself referring to him as a soldier. In fact, this label became so fixed in my head that when I was sorting through my photographs of xperience with Pritchard’s artifacts and archival file significantly directed my research as I have started looking at more museum studies articles and books on how curators negotiate incorporating narrative within exhibitions, and also the role that the public plays in their interpretations. I am finding it endlessly fascinating how key choices made by the curator can cue certain readings from the public, yet also how each visitor’s lived experience often redefines each interpretation. Luckily for me there is a significant amount of literature that touches on narrative theory in museums, as well as the opportunity to ask questions of the great staff at the Huron County Museum and Archives.

xperience with Pritchard’s artifacts and archival file significantly directed my research as I have started looking at more museum studies articles and books on how curators negotiate incorporating narrative within exhibitions, and also the role that the public plays in their interpretations. I am finding it endlessly fascinating how key choices made by the curator can cue certain readings from the public, yet also how each visitor’s lived experience often redefines each interpretation. Luckily for me there is a significant amount of literature that touches on narrative theory in museums, as well as the opportunity to ask questions of the great staff at the Huron County Museum and Archives. I also thought I might take the time to answer a question I receive often in terms of the artistic component of this project – which is “Why analog photography?” To be honest its a question I ask myself repeatedly as well (usually after a long day in the darkroom when only one print turns out). I chose to work in an analog process for this project because I was hoping that my artistic practice would reflect my experience at the museum – essentially embodying the idea of “careful touch.” I’ve found that working and photographing the artifacts feels like a very reverent experience, so I want my artistic process to reflect this as I take the time to physically manipulate the photos in the darkroom. I also find that there are parallels between working with the artifacts and working with the prints in concerns to preservation and value. To me, an analog photograph has a certain amount of value due to the fact that there are normally limited prints (and even then each print might be a bit different from the last!) as well as a certain level of preciousness since each photograph takes such a long time to process and complete. Additionally, I have been getting to learn a bit more about preservation of artifacts from the Museum Technician, which has lead me to make connections to the steps taken to preserve an analog photograph – such as keeping it in the fixative chemical bath for the right length of time so that the light does not deteriorate the print, or the never ending quest to avoid dust. In this way, I find that the analog process simply connects my practice.

I also thought I might take the time to answer a question I receive often in terms of the artistic component of this project – which is “Why analog photography?” To be honest its a question I ask myself repeatedly as well (usually after a long day in the darkroom when only one print turns out). I chose to work in an analog process for this project because I was hoping that my artistic practice would reflect my experience at the museum – essentially embodying the idea of “careful touch.” I’ve found that working and photographing the artifacts feels like a very reverent experience, so I want my artistic process to reflect this as I take the time to physically manipulate the photos in the darkroom. I also find that there are parallels between working with the artifacts and working with the prints in concerns to preservation and value. To me, an analog photograph has a certain amount of value due to the fact that there are normally limited prints (and even then each print might be a bit different from the last!) as well as a certain level of preciousness since each photograph takes such a long time to process and complete. Additionally, I have been getting to learn a bit more about preservation of artifacts from the Museum Technician, which has lead me to make connections to the steps taken to preserve an analog photograph – such as keeping it in the fixative chemical bath for the right length of time so that the light does not deteriorate the print, or the never ending quest to avoid dust. In this way, I find that the analog process simply connects my practice.