An Unconquered Crime: Infanticide in Huron County

According to the Criminal Code of Canada, “a female person commits infanticide when by a wilful act or omission she causes the death of her newly-born child.” Using local resources, student Kevin den Dunnen explores local cases of infanticide in the late 19th and 20th century (the period for which Gaol records are readily available), and the contemporary attitudes towards this act at home and abroad.

Through the 19th and 20th centuries, Huron County newspapers printed cases of infanticide, or the act of killing an infant, allegedly taking place in other countries and cultures. These articles often framed this the context of the supposed inferiority of cultures without the influence of Western Christianity. (1) However, the prevalence of infanticide in Huron County and surrounding areas during this same time period disproves any claims of cultural immunity to infanticide in southwestern Ontario’s Christian-dominated communities.

There are many social factors that contributed to the infanticides that occurred in Huron County. In the 19th and 20th centuries, a birth outside wedlock threatened an unmarried woman’s status in society. Many known infanticide cases in Huron County involved these young, unmarried women. Contributing to the devastating decision to commit infanticide was the lack of local social services available to single women needing help to provide for their child. As such, infanticide has been present in Huron County for much of its history.

The story of a Huron County woman called Catherine and her child exemplifies many of these themes. Catherine was a 30-year-old servant and unmarried woman working in Goderich Township in 1870. She had gone to her doctor that year claiming her body was swelling. The doctor suspected that she might be pregnant, but Catherine did not agree. Later on, her employer came home to find some of her work unfinished and could not find her. Upon searching, they found her sitting in a privy. After telling her to leave the privy several times, Catherine went to the house. Upon inspection of the privy the next morning, the house-owner and a doctor found a dead child in the privy vault covered by paper and a board. In his subsequent report, the coroner believed that the baby was born alive. (2) Upon first reading, this story appears to be a cold-blooded case of infanticide, but the reality of the society around Catherine makes the situation far more complex.

Turn of the 20th century newspapers in Huron County printed or reprinted articles from larger news agencies about non-Christian societies in India, China, and Hawaii and touted their supposed propensity of infanticide. These stories promoted the positive influence of Christian conversion outside of Canada, even though infanticide was also a local issue. Figure 1 is one such article from The Exeter Times, published on Feb. 1, 1894. This article states that the work of missionaries converting foreign societies to Christianity would “introduce the mercy of the Gospel among the down-trodden of heathenism.” The uncredited author claimed non-Christian cultures frequently committed infanticide but stopped when they converted to Christianity. (3) There is an apparent hypocrisy in these newspapers portraying other societies as uncivilized while the same issues were happing contemporaneously in their own Ontario communities. Figure 2 shows an article from The Brussels Post, dated Nov. 20, 1902. In this article, the author argues the need for laws restricting the distribution of alcohol. They state that such opportunities to change society are “the call of God” whose influence had already “conquered great evils, such as infanticide.” Yet, infanticide still occurred in the paper’s own region.

How prevalent an issue infanticide was throughout Huron County’s history is difficult to know, because many cases likely went unreported. A large proportion of the known cases involved single mothers of illegitimate children. However, some scholars suggest that more cases of undocumented infanticide frequently occurred in Western societies. These theories argue that hidden infanticide by married couples might partly explain changing gender ratios in select western societies. They claim this was a way of tailoring gender to fit family needs, like wanting males to help with farming. (4) Single women living and working away from their families would face greater difficulties concealing a birth without detection. Hidden infanticide drew attention from journals like the Upper Canada Journal of Medical, Surgical and Physical Science in 1852. This journal argued that women should have to register their children immediately after birth to lessen the chance of hidden infanticide. (5) This call for registration suggests that the journal suspected or knew of infanticide cases where the mother did not register their child to hide its birth. This research indicates that communities like Huron County could have many cases of infanticide that county records do not include.

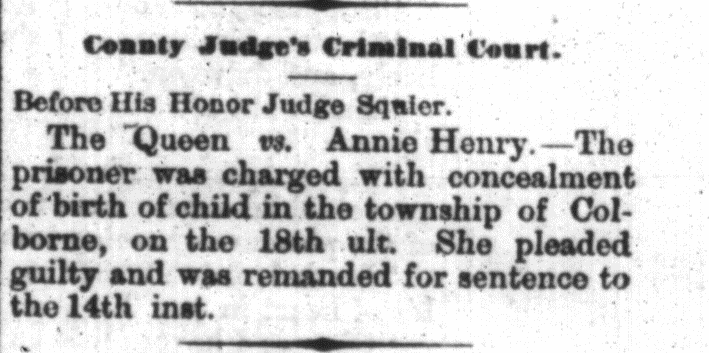

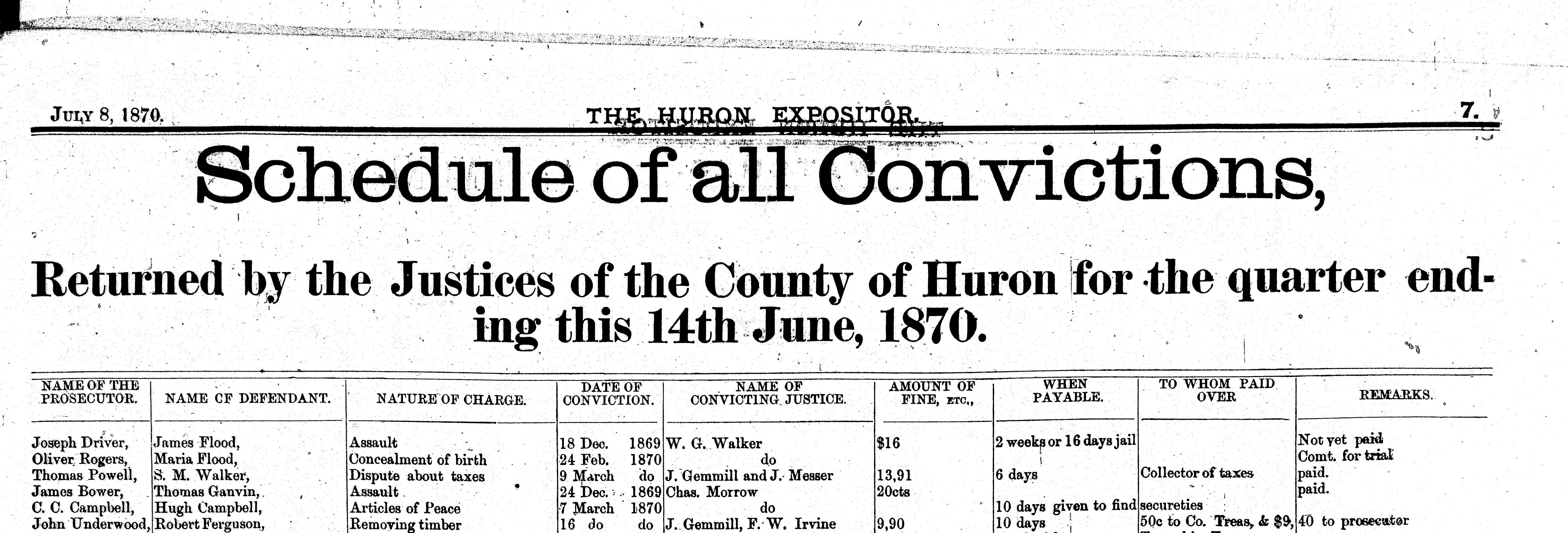

One record that is available for study is the “Huron County Gaol Registry.” The portion of the Registry currently available for research includes entries for every person who stayed at the Gaol from 1841-1922. There are at least 12 cases that list infanticide, concealment of birth, child exposure, or a related charge as the reason for committal (Figure 3 and 4). While not a staggeringly high number, these records only include the people sentenced to gaol for allegedly killing their infant or related crimes. If they were not apprehended or not committed to jail, they would not appear in the registry. Additional cases do appear in the local newspaper accounts (Figure 5) and coroner’s inquest records , including Catherine’s story . The registry shows that the first prisoner committed for infanticide came to the Gaol in 1846 and that a prisoner was committed for procuring drugs for an illegal abortion in 1920. While not demonstrating frequency with complete accuracy, the registry clearly does indicate that infanticide and other crimes resulting from unwanted pregnancies occurred in Huron County throughout the entire period documented from 1841-1922. These instances of infanticide would increase when including the records of nearby counties like Middlesex, Bruce, and Perth, which also had reported infanticide cases during the same period. There was therefore no reason to look to other countries to find the circumstances that fostered infanticide: Huron County residents could see the evidence in their own towns and the surrounding counties.

Figure 1: “The Safe Arm of God,” The Exeter Times, 1894-2-1, Page 6

Figure 2: “Prohibition Notes,” The Brussels Post, 1902-11-20, Page 4

Figure 3: The Huron Expositor, 07-22-1881, pg 5.

Figure 4:The Huron Signal, 06-10-1887, pg 4.

Figure 5: The Huron Signal, 12-10-1880, pg 1.

Mothers faced most of the blame for infanticide from the legal system and contemporary journalists for reported cases. However, this viewpoint often neglects to consider both the devastating judgements placed upon these women for their unwanted pregnancies, and the lack of support available to help struggling mothers. Of the cases involving infanticide, concealment of birth, or abortion found in the Huron County newspapers and Gaol records, a large number involve young women under 25 years old and illegitimate children (the offspring of a couple not married to each other). For example, a case from 1864 involves a 15-year-old unmarried female servant; a case from 1877 involves a 22-year-old single female servant; a case from 1880 involves a 17-year-old female servant. As servants, these women were dependent on wage labour. With the birth of a child, the woman would have to give up employment to care for the baby, as without the security of legal marriage the father would often refuse any support. Her ability to care for herself, let alone the child, declined greatly after giving birth. In addition, women faced religious and societal pressures to remain chaste until marriage. Bearing an illegitimate child proved to society that a woman was unchaste. (6) Women who gave birth to illegitimate children, no matter the circumstances of their conception, would face harsh judgement from their communities, which could impact their ability to find new work or to be married. These women with illegitimate children immediately became outcasts. This happened because Christian societies at the time judged much of a single woman’s morality and value according to her chastity. (7) As such, women of this period faced significant social judgement if they had an illegitimate child. The idea of concealing the child’s birth may have appeared to be the only choice for single mothers hoping to retain their ability to earn a living, maintain their place in society and avoid becoming an outcast, which could lead to cases of infanticide and child abandonment.

The lack of available social services in Huron County before the 20th century could also factor into these cases of infanticide. Before Huron County’s House of Refuge opened near Clinton in 1895, the only municipal building available for social services was the Huron County Gaol. There was no local lying-in hospital or home for unwed mothers. During this period, the Gaol often housed the elderly, destitute, and sick. Some lower tier municipalities made the choice to commit unwed mothers to gaol to give birth, and multiple women would have their babies behind bars at the Huron Gaol. This was an inexpensive way to house the mother and child until such a time she could return to the labour market. A young woman faced with the birth of an illegitimate child in Huron County would therefore have little support and few options available should she struggle to care and provide for her baby, and may have to bear the stigma of being committed to gaol regardless of committing a crime.

While newspapers like The Exeter Times and Lucknow Sentinel reprinted articles featuring infanticide as a cautionary tale to criticize and condemn outside cultures and to promote the positive influence of western Christianity, infanticide remained prevalent in their own communities. Stories like that of Catherine demonstrate the difficult circumstances that sometimes drove women to commit infanticide. Having an illegitimate child immediately lessened the perceived status and life options of a young woman in respectable Christian Southwestern Ontario society. Also contributing to the devastating decision by some of these young women to commit infanticide was the lack of social services available to help them provide for a child. As such, infanticide was not a conquered issue for the residents of Huron County in the 19th and early 20th century.

Sources:

- (1) Nicola Goc, Women, Infanticide, and the Press, 1822-1922: News Narratives in England and Australia (New York, NY: Routledge, 2016), 28.

- (2) Coroner’s Report #365 Huron County Archives, Unnamed baby of Catherine J.

- (3 “The Safe Arm of God,” The Exeter Times, February 1, 1894, p. 6.

- (4) Gregory Hanlon, “Routine Infanticide in the West 1500-1800,” History Compass 14, no. 11 (2016): pp. 535-548, https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12361, 537.

- (5) Kirsten Johnson Kramar, Unwilling Mothers, Unwanted Babies: Infanticide in Canada (Vancouver, BC: UBC Press, 2006), 97.

- (6) Nicolá, Women, Infanticide, and the Press, 21.

- (7) Nicolá, Women, Infanticide, and the Press, 21.

Further Reading

Find an index of coroner’s inquests on our Archives page (scroll to the bottom to find indexes and finding aids).

Find more stories from Huron’s past through a search of Huron County’s historical newspapers online!